Once a voice of authority, the decline of trust in the press has mirrored the rise of a more fragmented, polarized media world.

This article is part of The Poynter 50, a series reflecting on 50 moments and people that shaped journalism over the past half-century — and continue to influence its future. As Poynter celebrates its 50th anniversary, we examine how the media landscape has evolved and what it means for the next era of news.

“This is my last broadcast as the anchorman of the ‘CBS Evening News.’”

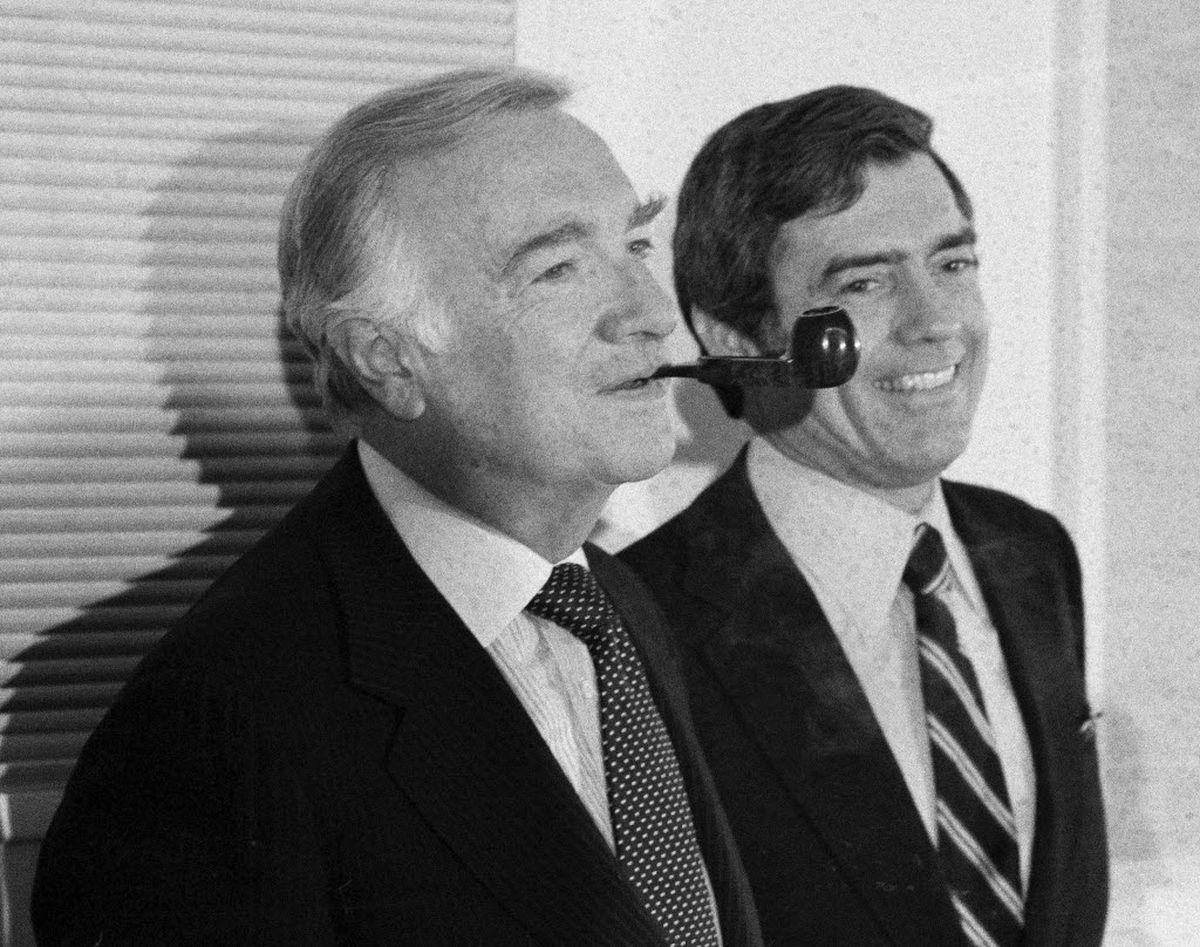

A seated Walter Cronkite, in a dark blue suit and striped tie, looked directly at the camera. It was March 6, 1981, and the celebrated journalist, who had been the voice of authority through many of America’s most tumultuous days, wanted his audience to know that this was a moment he had long planned. But nevertheless, he acknowledged, it came with sadness.

“For almost two decades, after all, we’ve been meeting like this in the evenings,” he said. “And I’ll miss that.”

Cronkite, who had anchored the flagship evening TV news program since 1962, downplayed his departure. He framed it as a transition, a passing of the baton to Dan Rather. Cronkite promised he wasn’t going away. He’d return from time to time with special news reports.

“Old anchormen, you see, don’t fade away,” he said with a hint of a smile. “They just keep coming back for more.”

Then, just like that, Cronkite delivered his famous sign-off.

“And that’s the way it is.”

Cronkite was often cited as “the most trusted man in America.” For millions of viewers, his farewell symbolized the pinnacle of journalistic trust. He was the man they relied on, the one who shaped how they saw the world. But that trust didn’t last forever.

In the four decades since, trust in the media has been in steady decline. Cronkite’s departure is seen in hindsight as one of the last moments when Americans collectively turned to a single, authoritative news source. Whether that’s true or just a convenient fable, there’s no doubt that trust is much lower now.

Today, according to a 2024 Gallup poll, more than a third of U.S. adults (36%) report having no trust at all in the media for the third consecutive year. A Pew Research Center survey from earlier this year revealed that trust in national news media is lower among Republicans, with only 49% expressing some or a lot of trust in news organizations.

The trust that Cronkite once embodied has all but evaporated. The decline has been driven by many factors. Some of it had to do with Cronkite himself.

In the 1960s, the early days of network news, there was a great deal of tumult, said Al Tompkins, Poynter senior faculty emeritus. The Vietnam War. The assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and President John F. Kennedy. Cronkite, Tompkins said, was an important influence in helping people understand these cataclysmic events as they were unfolding.

Legendary broadcast journalist Judy Woodruff was a high school senior when Kennedy was shot. She recalled school being canceled and the national days of mourning that followed, held so people could watch the televised funeral.

“And I remember sitting on the floor of the living room two feet away from the TV set, glued for hour upon hour as Cronkite reported on the assassination.”

Woodruff also recalled Cronkite’s reporting of the arrest of Jack Ruby, who killed Lee Harvey Oswald — the man who killed the president.

“It was riveting. We all listened to Cronkite because he was the most believed person,” she said. “And of course, then I got to know him much later, when I went on and became a journalist.”

Tom Rosenstiel, a professor at the University of Maryland and the author of the forthcoming book, “The Next Journalism,” said Cronkite was very thoughtful. He wasn’t the guy who waved his arms and tried to get people to watch his program, he said. He was the guy who said, “This is what we know. This is what we don’t know.”

“There was something about Cronkite that made him extremely trustworthy in his demeanor, in his style, and in the approach he took,” Rosenstiel added.

The revered news anchor died in 2009 of cerebral vascular disease.

Cronkite’s sign-off marked the end of an era when broadcast television was the dominant news source for millions of Americans. Cable news and the internet eroded broadcast’s dominance, leaving behind a fragmented media world.

“I think part of it has to do with how many different sources of news are now available,” Woodruff said. “And the blurring of lines between news that is vetted and accurately sourced, versus news and information that’s just somebody’s opinion, or worse: news that is made up, or deliberately shared knowing that it’s false or the person is unwilling to admit that it’s false.”

More voices, Tompkins said, led to more ways of understanding the same story. “If I only have you as my source of information, then the way you tell me the story is going to be the only way I understand the story,” he said. “And I have to trust you, because I don’t have any other person to trust. You’re the only one who knows.”

But things become gray when there are many versions of the story. Tompkins noted that’s when people may start to align with a particular point of view or prefer one way of reporting over another.

“Like any commodity, the more sources you have of that commodity, the more fractionalized the audience is going to be,” he said. “If you only have one grocery store, then that’s all you got to choose from. When you start getting 15 grocery stores, you start fracturing the audience into market segments. And that’s exactly what’s happened with media.”

Amy Mitchell, the executive director of the Center for News, Technology & Innovation, said the development of the internet fundamentally changed how people access information.

“It opened up a wealth of places people could turn to, could rely on,” she said, noting these sources could come from outside of someone’s local area or even country. She added, “Social media brought even more choice in terms of individuals that would be sharing and getting information to you.”

Mitchell also pointed to two other key shifts: the ability to engage directly with the information, whether by commenting, adding to a story or participating as a citizen journalist, and the rise of fact-checking and verification tools. “And as those develop, the automatic trust in an institution as the place to rely on declined,” Mitchell said. “One can see how, naturally, automatic trust would decline as people have more to consider, as they’re making more choices.”

Kerwin Speight, a Poynter faculty member and local news expert, recalled a time when skepticism from some audiences existed, but trust in the press was generally strong.

“Part of the challenge now is that, because you have information coming from so many different places, and it is saying so many different things, it is harder to know who to trust,” he said.

Speight pointed out that this shift means audiences must do more work to discern what’s real and hold those responsible for false or inaccurate information to account.

“The individual has to decipher or ask a second layer of questions: ‘Is this real? Is this photo real? Did this really happen?’”

Speight said trust is a two-way street. It’s on the media to make sure that not only are we telling the truth and that we’re building trust, but we’re being transparent in how we report.

Rosenstiel believes the press itself erodes trust by not being clear about its intellectual, philosophical underpinnings.

“There’s a kind of intellectual sloppiness in journalism about who we are, and what we’re doing, (that) has also created distrust,” he said, “because people think, ‘You know what you’re saying is BS. You have a point of view.’ Or, ‘You’re not neutral.’”

Trust is very complex, said Katerina Eva Matsa, who directs news and information research at Pew Research Center. It’s driven by political identities and other personal factors.

“It is important to think about this, because it’s not like there’s no trust in anything,” she said. “But the places that people put their trust in are very, very different.”

In 2006, Cronkite had a conversation with the then-NCAA president Myles Brand in front of a large audience. Brand, acknowledging Cronkite’s advocacy for good reporting, asked him what he considered to be the bedrock principle of journalism that is missing from some of the cable stations.

Cronkite pointed to core values of journalism. Honesty. Fairness. Truth. Totality of the story. Telling both sides of a controversial issue.

He said even the better newspapers had struggled, and lost readership.

“I think that the good journalists, the old journalists, the old-timers in there, are fighting the good fight and trying to hold onto what we know to be the principles of good journalism,” Cronkite said. “And I think we’re succeeding most of the time. But I see a little few cracks appearing in the walls there.”

News

🐧 – Giorgio Armani, the Italian designer who revolutionized the shape of fashion, dies at 91

MILAN, Sept 4 (Reuters) – Italian designer Giorgio Armani, one of the biggest names in the world of fashion has…

🐧 – Charles Bronson Like You’ve Never Seen Him: Daughter Zuleika Reveals the Man Behind the Tough-Guy Image

He was the steely-eyed vigilante of Death Wish, the hardened outlaw in The Magnificent Seven, and one of Hollywood’s most…

🐧 – ‘Today’ Show Fans, Savannah Guthrie Revealed Emotional News About Sheinelle Jones’ Return

After a leave of absence and the death of her husband Uche Ojeh, Sheinelle will return to the NBC show…

🐧 – Celebrities Who Lost EVERYTHING Behind Bars: From Red Carpets to Prison Cells

From Hollywood’s elite to global music icons and superstar athletes, these celebrities had it all — fame, fortune, adoration, and…

🐧 – Dan Rather Is 93 and Still Breaking Stories: The Legendary Newsman Refuses to Slow Down

He may have signed off from the anchor desk two decades ago, but Dan Rather isn’t done telling the truth….

🐧 – Paul Newman Name The Most EVIL ACTORS Of Hollywood’s Golden Age

Beneath the glitz, glamour, and golden lights of Hollywood’s Golden Age lurked a disturbing truth — and Paul Newman wasn’t…

End of content

No more pages to load