He cheated death—or at least, he tried to. And in doing so, he built a tomb unlike anything humanity has ever known.

For more than 2,000 years, the burial chamber of China’s first emperor has remained sealed beneath a vast earthen mound, guarded by silence, legend, and fear. Hidden near the famous Terracotta Army, this underground kingdom is rumored to contain rivers of liquid mercury, lethal mechanical traps, and a perfect miniature version of the empire itself.

Even in 2025, with modern technology at humanity’s disposal, scientists refuse to open it.

The question is no longer what lies inside—but whether opening it would unleash dangers we are not prepared to face.

More than two millennia ago, China did not exist as a single nation. Instead, the land was fractured into rival kingdoms locked in near-constant warfare—a brutal era known as the Warring States period. Each state had its own laws, currencies, scripts, and armies. Peace was rare. Survival demanded conquest.

In 259 BC, in the western state of Qin, a prince named Ying Zheng was born. At just 13 years old, he ascended the throne after his father’s death. Though young, he was surrounded by ambitious ministers and generals who helped him hold power while he matured into a formidable ruler.

Ying Zheng wanted more than survival. He wanted unity.

Over the next decade, he launched relentless military campaigns against the six rival states—Han, Zhao, Wei, Chu, Yan, and Qi. Using disciplined armies, advanced weapons, and ruthless strategy, Qin crushed them one by one. By 221 BC, for the first time in Chinese history, the land stood united.

Ying Zheng declared himself Qin Shi Huangdi—the First Emperor of China.

He believed his reign marked the beginning of an eternal age.

Building an Empire That Would Last Forever

Qin Shi Huang immediately set about reshaping the world. He standardized writing so citizens across the empire could communicate. He unified currency, weights, and measurements, regulated road widths, and replaced regional rulers with officials loyal only to him.

To defend his borders, he ordered the linking and expansion of northern walls—early foundations of what would become the Great Wall of China. Inside the empire, massive road networks and canals allowed armies and goods to move with unprecedented speed.

Yet as his control over the living world expanded, a darker fear consumed him.

He was terrified of death.

Obsessed with immortality, Qin Shi Huang sent scholars, doctors, and alchemists across the land in search of eternal life. Some sailed toward mythical islands. Others brewed potions meant to halt aging. Among the substances he consumed was mercury—then believed to hold life-preserving properties.

In reality, it was slowly poisoning him.

Unable to conquer death, the emperor turned to the next best thing: ruling forever in the afterlife.

A Kingdom Beneath the Earth

From the moment he became king, Qin Shi Huang began planning his tomb. What he envisioned was not a grave—but an empire underground.

Over 700,000 laborers were conscripted to build it: soldiers, craftsmen, prisoners, and peasants drawn from across the newly unified land. Construction continued for nearly four decades and was still underway when the emperor died in 210 BC.

The site was chosen at Mount Li, near the capital, for its symbolic and natural wealth—gold to the north, jade to the south. The tomb complex was modeled after the imperial capital itself, complete with walls, watchtowers, palaces, and administrative buildings.

The underground city was divided into inner and outer sections, mirroring the structure of the living empire. Inside were stables, kitchens, storehouses, gardens, ceremonial halls, and even entertainment—bronze birds, musicians, and performers meant to serve the emperor’s spirit.

Drainage systems, underground dams, and sealed walls protected the complex from flooding. Engineers planned for groundwater nearly 100 feet below the surface. Nothing was left to chance.

The scale is staggering. The mausoleum complex covers nearly 38 square miles, larger than many modern cities. Even after decades of excavation, archaeologists believe only a fraction has been uncovered.

And guarding it all, to the east—the direction of Qin’s former enemies—stood something extraordinary.

The Army That Waited in Silence

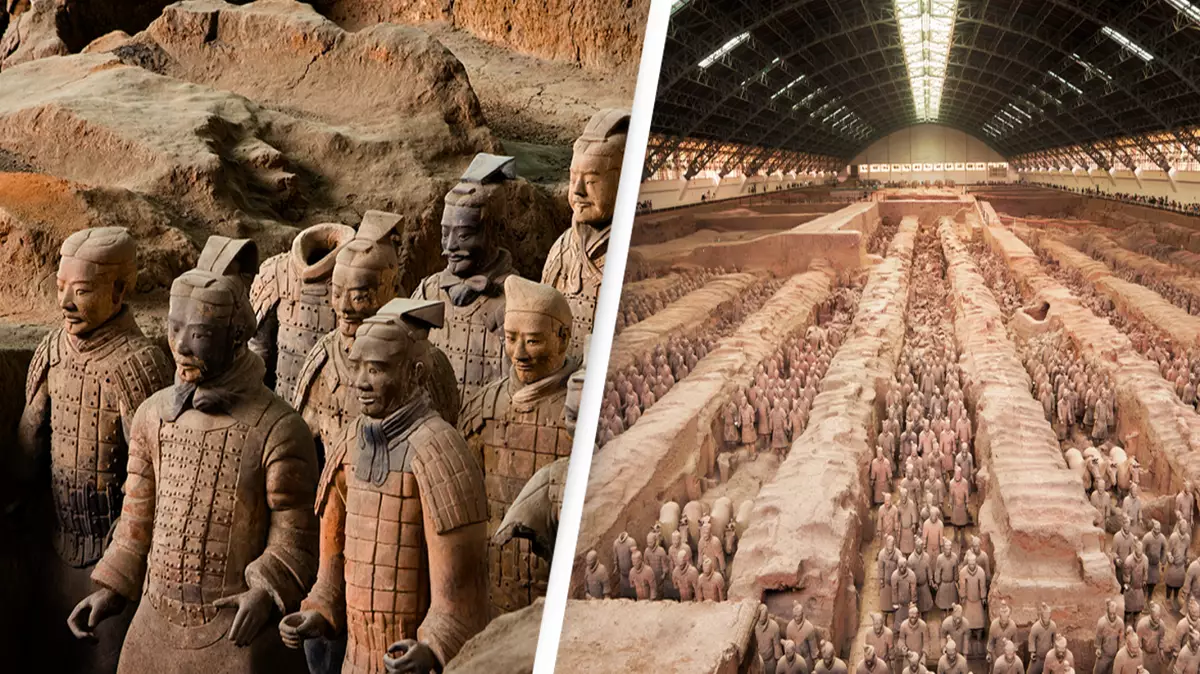

In 1974, farmers digging a well near Xi’an struck something hard beneath the soil. What they uncovered changed history.

Beneath their feet lay ranks of life-sized clay soldiers—thousands of them—standing in battle formation. Today, we know them as the Terracotta Army.

More than 8,000 warriors have been uncovered so far, each one unique. Different faces. Different hairstyles. Different expressions. Some look fierce, others calm, some almost human enough to breathe.

They were accompanied by chariots, cavalry, generals, archers, and foot soldiers—many holding real bronze weapons still sharp after two millennia. Nearby pits revealed acrobats, musicians, officials, animals, and birds—an entire court frozen in clay.

Originally, every figure was painted in vivid color. But exposure to air caused the pigments to peel away within minutes. That devastating loss taught archaeologists a hard lesson: the underground environment had preserved these treasures perfectly—and the outside world could destroy them instantly.

It is one of the main reasons much of the complex remains untouched.

The Tomb at the Center of It All

At the heart of the necropolis lies the emperor himself, buried beneath a massive earthen mound shaped like a low pyramid.

No one has entered it.

Ancient historian Sima Qian, writing a century after Qin Shi Huang’s death, described the tomb in chilling detail. Inside, he claimed, was a complete model of the empire. Rivers and seas made not of water, but liquid mercury. Palaces and towers filled with treasure. A ceiling painted with stars and constellations.

And traps.

Crossbows rigged to fire automatically at intruders. Weapons hidden in walls and ceilings, designed to kill instantly.

For centuries, historians dismissed these accounts as legend.

Then scientists tested the soil.

In the early 2000s, chemical surveys around the burial mound revealed mercury levels hundreds of times higher than normal—some readings exceeding 1,400 parts per billion. The distribution matched the ancient descriptions of flowing rivers.

The legend was no longer just a story.

Experts now believe mercury vapor may still be sealed inside the tomb. Inhaling even small amounts can cause severe neurological damage—or death. Opening the chamber without perfect containment could be catastrophic.

And the traps? Ancient spring-loaded mechanisms made of metal can remain functional for centuries if undisturbed.

The danger is real.

Why the Tomb Remains Sealed

Modern tools—ground-penetrating radar, magnetometers, and advanced scanning—have mapped the tomb’s outline. Scientists know where it is. They know its size.

But they will not break the seal.

Preservation is the greatest concern. If the tomb is opened too soon, priceless information could be lost forever—just as the Terracotta Army’s colors vanished in moments. Chemical reactions, oxygen exposure, and structural collapse could destroy what time itself has preserved.

Yet waiting carries risks too. Earthquakes, flooding, pollution, and looting all threaten the site. To balance these dangers, researchers are experimenting with non-invasive methods and robotic probes that might one day explore the tomb without opening it.

For now, the emperor sleeps undisturbed.

A Question for the Future

This is not about gold or treasure. It is about understanding how ancient China viewed power, death, and the universe. The tomb of Qin Shi Huang may be the last great untouched archaeological site on Earth—a sealed time capsule from the birth of an empire.

Should we open it now—or let the First Emperor keep his secrets?

For over 2,000 years, he has waited beneath the earth, surrounded by an army that never marched, rivers that never dried, and traps that may still be ready to kill.

Perhaps immortality was never about living forever.

Perhaps it was about never being disturbed at all.

News

🎰 Camera Thrown Into Mel’s Hole, What They See Terrifies The Whole World

In the hills of eastern Washington, a story refuses to stay buried. A bottomless pit.A pathway to something not meant…

🎰 After 54 Years, The TRUE Identity Of ‘D.B. Cooper’ Has FINALLY Been Revealed!

He was the first man in U.S. history to hijack a plane for ransom.He boarded a commercial jet under a…

🎰 Saudi Arabia Buried Millions of Gallons of Salt Water Under Sand, Result is Unreal

What if Saudi Arabia’s water crisis had a buried solution? Scientists explore hidden riverbeds beneath the desert that may offer…

🎰 Virgin Mary in the ICU? Nurse Sees Woman Next to Patient… Cameras Show NO ONE There

A miracle of the Virgin Mary happened in the ICU of a hospital in Chicago at 3 in the morning….

🎰 Inside the Vatican After the Death of a Pope: Protocol, Power, and the Race Against Chaos

When a pope dies, the Vatican does not pause to grieve—not at first. It moves. Centuries of experience have taught…

🎰 Pope Francis’ final hours: Easter message, greeting the crowd, early morning stroke

When Pope Francis appeared on the loggia of St. Peter’s Basilica a few minutes after noon Roman time on Easter…

End of content

No more pages to load