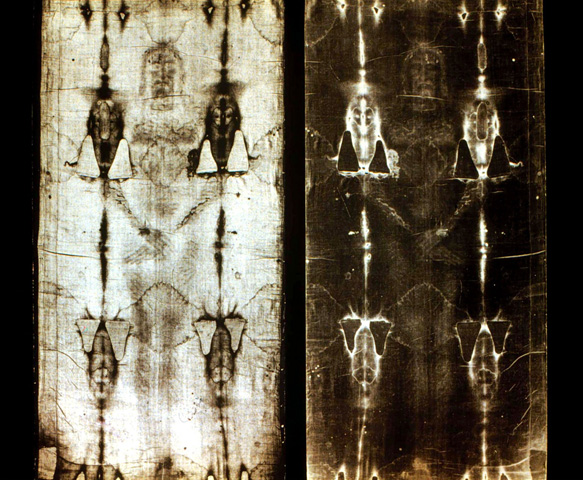

Few objects in human history have inspired as much devotion, controversy, and relentless investigation as the Shroud of Turin. For centuries, it has stood at the crossroads of faith and skepticism: revered by millions as the burial cloth of Jesus Christ, dismissed by others as the most brilliant medieval forgery ever devised.

For believers, the shroud is a silent witness to the Resurrection—a fifth gospel written not in ink, but in blood. For skeptics, it is a masterwork of deception, perhaps even the product of a Renaissance genius like Leonardo da Vinci, created to exploit pilgrims hungry for miracles.

For more than six hundred years, neither side yielded.

But in the 21st century, philosophy gave way to precision. Science entered the debate—not with reverence or ridicule, but with instruments, data, and questions no one could ignore.

And what science found did not settle the argument.

It shattered it.

When the Shroud Became a Crime Scene

Modern researchers no longer approached the shroud as a religious icon. They treated it as evidence. A cold case. A biological hard drive quietly recording two thousand years of history.

Geneticists, physicists, forensic pathologists, and spectroscopists examined every thread. X-rays scanned the fibers. Bloodstains were broken down into molecules and atoms. Dust trapped between linen threads was analyzed like soil from an archaeological dig.

Scientists expected simple answers: traces of pigment, evidence of a medieval artist, perhaps DNA from a single individual.

Instead, they found something so complex that it dismantled both skeptical explanations and traditional assumptions alike.

The shroud was no longer just fabric.

It was a map.

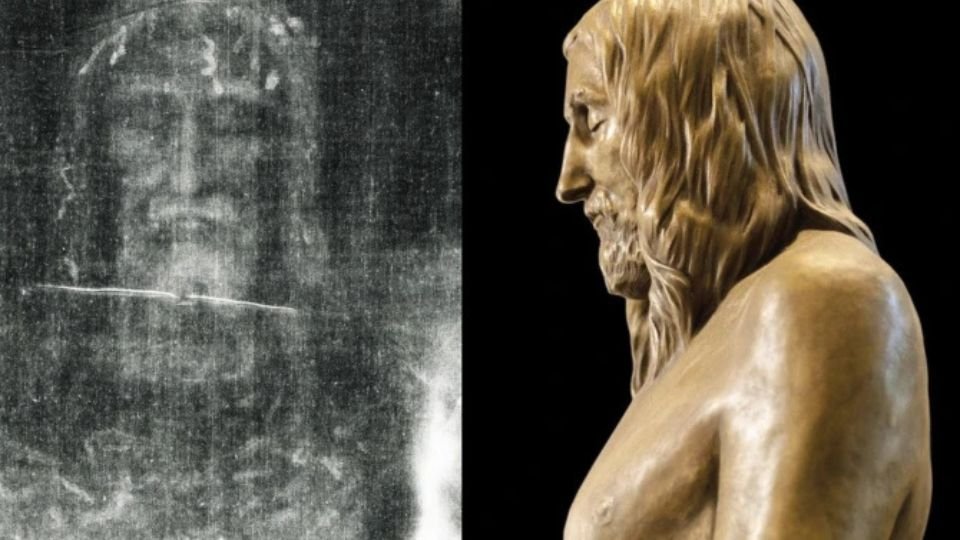

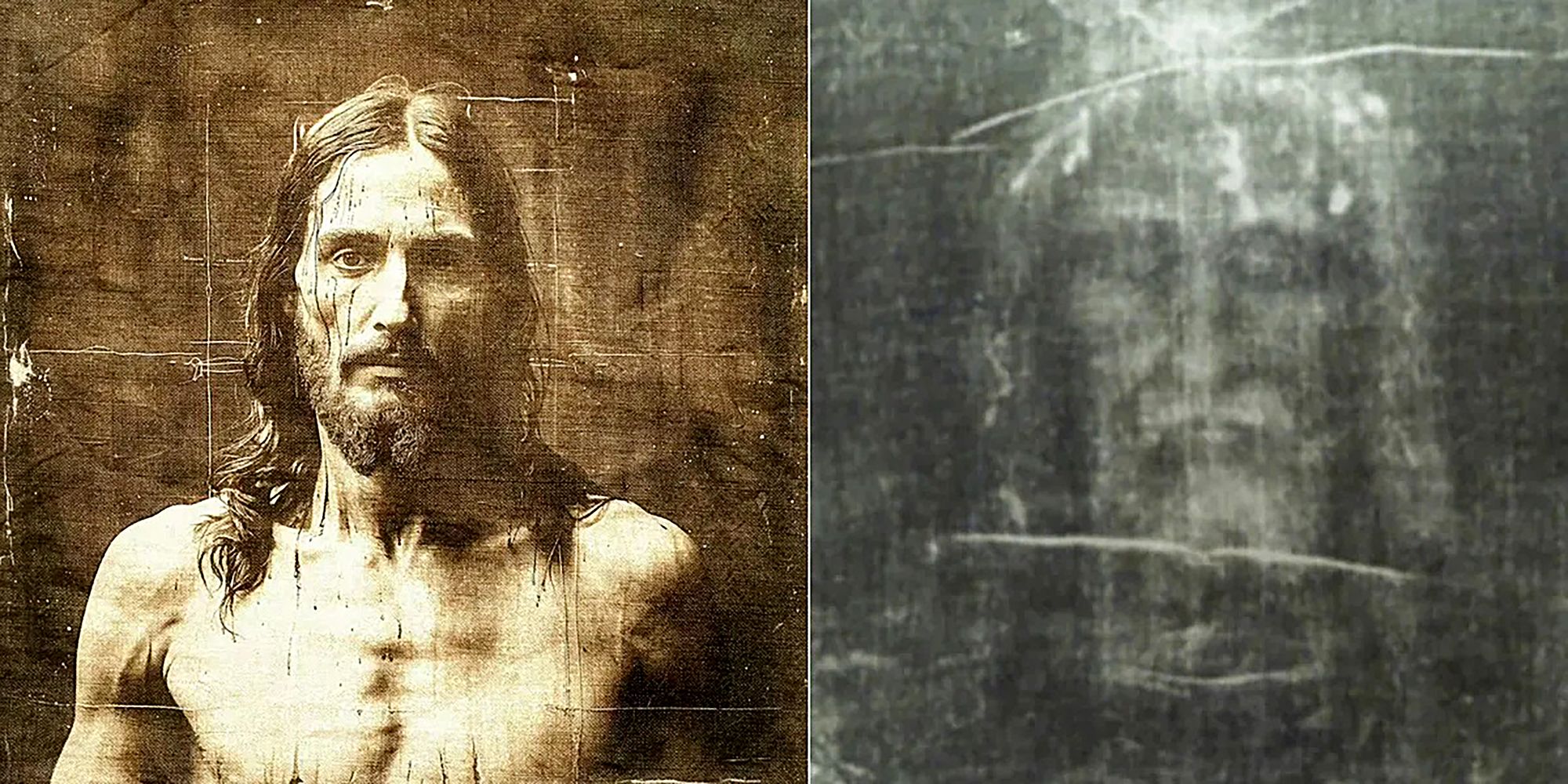

The First Shock: A Face Revealed

To understand why modern discoveries were so unsettling, we must return to the moment when humanity first truly saw the man on the cloth.

That moment came on May 28, 1898, in Turin.

A lawyer and amateur photographer named Secondo Pia was granted rare permission to photograph the shroud during a public exhibition. Photography at the time was slow and difficult. Pia hauled a massive camera onto scaffolding inside the cathedral and exposed two large glass plates using blinding magnesium flashes.

Late that night, alone in his darkroom, Pia lowered one plate into the developing bath.

As the image emerged, he nearly dropped it.

On the photographic negative—where light should reverse into darkness—there appeared not a vague stain, but a sharp, high-contrast positive image: a man’s face, eyes closed, nose broken, beard forked, bruises clearly visible.

For the first time, the shadow on the cloth became a man.

This was not how drawings behave when photographed. Paintings, charcoal sketches, and even blood-based images distort under negative exposure. But the shroud did the opposite. It behaved like a photographic negative itself—producing a lifelike, anatomically correct image when reversed.

The implication was staggering.

Who in the Middle Ages understood photography—eight centuries before its invention? Who could create a perfect negative image without any way to preview the result?

No one.

The shroud did not behave like art. It behaved like an imprint—a captured moment.

DNA in the Fibers

The greatest secrets of the shroud, however, were not in the image itself.

They were in the dust.

In 2015, a research team led by Professor Gianni Barcaccia of the University of Padua was granted unprecedented access to microscopic material trapped deep within the linen. Using sterile micro-vacuum devices, they collected pollen, dust, and organic fragments from between the warp and weft threads—areas sealed from modern contamination.

The samples were analyzed using next-generation sequencing, focusing on mitochondrial DNA. Unlike nuclear DNA, mitochondrial DNA survives far longer and provides powerful clues about geographic origin.

What emerged left the researchers stunned.

This was not the DNA of one person.

It was the DNA of humanity.

Published in Nature Scientific Reports, the findings showed genetic markers from across the globe: the Middle East, Western Europe, North and East Africa, South Asia, and even East Asia.

Chinese haplogroups. Indian genetic signatures. African lineages. European traces.

All on a single cloth.

If the shroud were a medieval forgery made in France, European DNA should have dominated. If it were a relic that never left Jerusalem, Middle Eastern DNA should have prevailed.

Instead, the cloth carried the biological fingerprints of the ancient world.

A Cloth That Traveled the World

The explanation was as astonishing as the data.

The shroud was not static. It was a traveler.

When researchers mapped the genetic distribution, it aligned almost perfectly with a journey described in early Byzantine, Syrian, and Arabic sources. Folded to display only the face—known as the tetradiplon—the relic moved along major trade routes.

From Jerusalem, it traveled to Edessa in the second century, a Silk Road crossroads where merchants from China, India, Persia, and Arabia passed through. There, pilgrims touched it, breathed near it, kissed its casing.

Microscopic traces accumulated.

From Edessa, it moved to Constantinople, then Athens, and finally to France in the 14th century—precisely where history records its appearance.

No medieval forger could have engineered this biological record. DNA cannot be painted on. It settles naturally, invisibly, over centuries.

The shroud is not contaminated.

It is documented.

Pollen That Speaks

Botany confirmed what genetics suggested.

Independent pollen studies by Israeli botanist Avinoam Danin and Swiss forensic scientist Max Frei identified 58 plant species trapped in the linen.

Seventeen were European. Expected.

The rest were not.

Many came from Anatolia and the Middle East—matching the shroud’s ancient route. But the most remarkable discovery was pollen from plants that grow nowhere else on Earth: species native only to the narrow corridor between Jerusalem and Jericho.

At the center of this finding was Gundelia tournefortii—a thorny desert plant.

Its pollen accounted for nearly half of all samples.

This plant blooms around Jerusalem during early spring, precisely during Passover. Its long, rigid thorns match descriptions of the crown of thorns.

The pollen clustered around the head and shoulders.

Pollen cannot be forged.

It is a geographic fingerprint.

Blood That Tells a Story

For centuries, skeptics claimed the bloodstains were paint.

In 2017, that claim collapsed.

Using electron microscopy and Raman spectroscopy, researchers confirmed the stains were real human blood—type AB. Rare, yet found on other ancient Christian relics.

But this blood was abnormal.

It contained extreme levels of creatinine and ferritin—markers of severe trauma, dehydration, and muscle destruction. These biochemical signatures appear only in cases of prolonged torture and catastrophic injury.

This was not symbolic blood.

It was the blood of a man beaten beyond endurance.

The chemistry recorded a body already dying before crucifixion began.

No artist can fake that.

The Radiocarbon Problem—and Its Collapse

In 1988, radiocarbon dating seemed to end the debate. Three laboratories dated the cloth to the Middle Ages.

But decades later, scientists identified the fatal flaw.

The sample was taken from a heavily handled, repaired corner of the shroud—contaminated with cotton threads, dye, and centuries of grime. Chemist Ray Rogers demonstrated that the tested material was not original linen at all.

They dated a medieval repair.

Not the shroud.

In 2022, a new method—wide-angle X-ray scattering—measured the aging of the linen’s cellulose at the atomic level. This technique bypassed contamination entirely.

The results placed the fabric firmly in the first century.

Its molecular structure matched linen from Masada, dated between 50 and 74 AD.

Science had reversed itself.

The Image That Should Not Exist

Still, one question remains.

How did the image form?

It is not paint. It penetrates only 200 nanometers into the fiber. It is a chemical alteration caused by oxidation and dehydration.

To reproduce it, scientists needed a burst of vacuum ultraviolet radiation—an intense flash lasting less than a billionth of a second.

Such energy does not occur naturally.

And it did not destroy the cloth.

The image also encodes perfect 3D information. Its intensity corresponds precisely to body distance. NASA analysis confirmed it.

Even coins on the eyes match Roman coins minted under Pontius Pilate in 29 AD.

Layer by layer—biology, chemistry, physics, history—the evidence converges.

Jerusalem. 30–33 AD.

A Silent Witness

Returned to its vault, the shroud remains silent.

But the data speaks.

It is not a painting.

Not a myth.

Not a medieval trick.

It is a forensic record of a real human being who suffered extreme trauma—and whose image was recorded in a way modern science still cannot fully explain.

Perhaps one day we will understand the flash of energy that left this trace.

Until then, the Shroud of Turin stands as a challenge—to science, to skepticism, and to belief itself.

Do you think science will one day explain a miracle?

Or are some truths meant to be approached not only with instruments—but with awe?

News

🎰 Legendary Salvage: 999-Year-Old Crucified Christ Statue Recovered from the Ocean Floor

From the dark depths of the ocean, a sacred treasure thought lost to time has risen again. A legendary 999-year-old…

🎰 Muslim Pilots burn BIBLES at Atlanta Airport… but then JESUS CHANGED EVERYTHING

My name is Amir. I’m 34 years old. And on March 22nd, 2016, I did something that should have destroyed…

🎰 With sincere love, Pope Leo XIV greets and embraces Marco, a person with a disability… and then the miracle happens.

With overwhelming compassion and boundless love, Pope Leo XIV warmly embraces Marco, a man living with a disability—an intimate moment…

🎰 A Declaration That Shook the Faithful: Pope Leo XIV and the Question of Mary

The Catholic world is shaking. In a move few anticipated and even fewer fully understand, Pope Leo XIV has issued…

🎰 They behe*ded a pastor in Saudi Arabia… but Jesus’s miracle shook the whole city

My name is Akram. I’m 42 years old. And on March 7th, 2018, I was seconds away from being executed…

🎰 The Morning the Church Spoke the Truth

The words would fall from his lips at dawn on January 3rd, in a chapel where no cameras waited. Ten…

End of content

No more pages to load