On the night of October 23rd, 1856 in Halifax County, Virginia, something impossible happened.

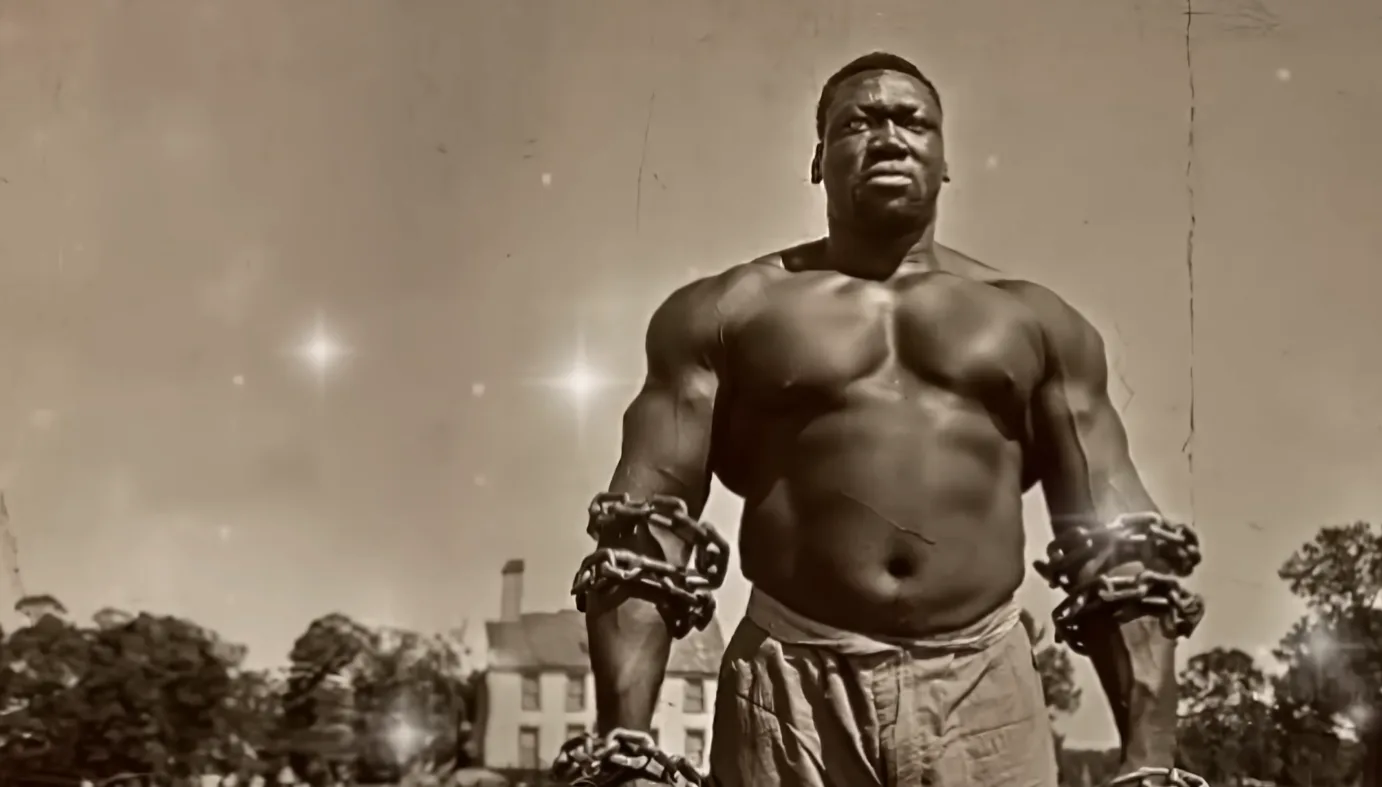

A man who had been displayed like a circus animal, studied like a laboratory specimen, and worked like a beast of burden for 15 years, finally broke his chains, literally.

Goliath stood 7 ft and 6 in tall. His hands could palm a man’s skull like a child holds an apple. His shoulders were so broad he had to turn sideways through most doorways. And on that October night, those hands that had carried impossible loads. Those arms that had been studied and measured and mocked became instruments of the most brutal justice Halifax County had ever witnessed.

By dawn, eight white men lay dead. The Blackwood family was erased from existence, and the entire South learned a terrifying lesson. There is no chain strong enough to hold a man who has decided he would rather die free than live enslaved. This is that story, and every word of it is true.

But to understand how Goliath became a killer, we must first understand how Cornelius Blackwood turned a human being into a weapon.

The auction block in Richmond, Virginia. September 1841. Cornelius Blackwood had come looking for field hands. strong backs to work his tobacco plantation in Halifax County. What he found instead was something he’d never seen in 40 years of slave trading. A boy maybe 15 years old, already 6t tall. But it wasn’t just the height, it was the proportions. Arms that hung past his knees, hands the size of dinner plates, feet that required custommade shoes, shoulders so massive they seemed deformed, the auctioneer was practically salivating.

“Gentlemen, I present the rarest specimen you’ll ever see. Direct from the Dinka region of Africa, a people known for extraordinary height. But this one, this one is special even among them.”

Cornelius pushed through the crowd. Up close, the boy was even more impressive and terrifying. Those eyes, dark and intelligent, watching everything, taking measure of every white face in the crowd.

“Can he work?” Cornelius called out,

“work. So this negro can do the labor of three men. I’ve seen him carry £600 across a warehouse. 600 without strain.”

The bidding started at £3,000. Already astronomical for a single slave. Cornelius bid 3500. A plantation owner from South Carolina went to 4,000. Cornelius counted with 4500. The South Carolina man shook his head and stepped back. Too rich for his blood.

“sold to Mr. Cornelius Blackwood of Halifax County for $4,500.”

The most expensive slave Cornelius had ever purchased. But as he looked at those massive hands at that towering frame, he was already calculating. This wasn’t just a field hand. This was an attraction, an investment. This was going to make him rich.

The boy spoke almost no English when he arrived at Blackwood Plantation. Just a few words picked up on the slave ship during the middle passage. His African name was unpronouncable to Cornelius’s ears. Something with clicks and tones that sounded like music. So Cornelius gave him a new name. A joke. Really? Biblical mockery.

“You’re Goliath now,” he announced at dinner that first night, making his wife and two adult sons laugh. “The giant who got killed by a little shepherd boy. Fitting, don’t you think?”

Goliath, the name the boy would carry for the rest of his life, stood silent in the corner of the dining room. His head nearly touched the ceiling. The house slaves stared at him like he was some kind of monster.

Master Blackwood’s youngest son, Jacob, tossed a piece of bread at Goliath’s feet. “Pick that up, giant. Let’s see you bend down.”

Goliath didn’t move. Didn’t even look at the bread.

Jacob stood up, face reening. “I said, pick it up, you big”

“Jacob.” Cornelius’s voice was calm, but firm. “Sit down. He doesn’t understand English yet.”

“Then maybe we should teach him.” Jacob grabbed a riding crop from the wall. The first strike caught Goliath across the shoulders. The second across the back of his legs. The third. Goliath turned slowly. And for just a moment, Jacob saw something in those eyes that made him step back. Something ancient and dangerous.

“That’s enough.” Cornelius stood, walking over to place himself between his son and his investment. “This negro cost me $4,500. You damage him, you pay for it. Understood?”

Jacob lowered the crop, but his eyes never left Goliath. “Yes, father.”

That night, in the cellar where Goliath had been chained, the only place with a ceiling high enough for him to stand upright, he touched the welts on his shoulders. They barely hurt. He’d endured worse on the ship coming over. Would endure worse here he already knew. But he remembered Jacob’s eyes. The fear that flickered there when Goliath had turned around.

“They should be afraid,” he thought in his native tongue. “They should be very afraid.”

Within a month, Cornelius Blackwood had turned his newest acquisition into Halifax County’s greatest attraction. Every Sunday after church, plantation owners from across Virginia would ride out to Blackwood Plantation. $5 per viewing, $10 if you wanted to see, demonstrations of strength. Cornelius had built a special exhibition area, a large barn cleared of equipment with benches arranged in a semicircle like a theater or a gladiator arena.

Goliath would be led out in chains, heavy iron manacles on his wrists and ankles, connected by links thick as a man’s thumb. He’d learned enough English by now to understand commands. To know what was expected.

“Lift that,” Cornelius would order, pointing to a massive cotton bail, 300 at least. Goliath would bend, his chains rattling, and hoist the bail onto one shoulder. The crowd would gasp and applaud. Women would fan themselves both scandalized and thrilled.

“Now the barrel,” a water barrel, 400 lb when full. Goliath would lift it overhead with both arms, holding it there while the audience counted. 10 seconds, 20, 30, muscles standing out like ship cables under his skin.

But the real entertainment came with the fights.

“Who wants to see if three men can take down the giant?” Cornelius would call out.

There were always volunteers, young overseers from neighboring plantations, bored sons of wealthy families, sometimes even professional boxers looking to make a reputation. The rules were simple. Three men against Goliath. Fists only. First side to surrender loses. If the three white men won, they split $50. If Goliath won, he got an extra ration of food that week.

Goliath never lost.

Oh, they’d land punches. blacken his eyes, split his lips, crack his ribs. Three men can do damage even to a giant. But Goliath was patient. He’d wait, absorbing punishment until one of them got cocky, moved too close. Then one massive hand would shoot out, grab a throat, and lift a 200lb man off his feet like he weighed nothing. The man’s friends would try to pull him free, and Goliath would swat them away. Not even strikes really, just brushing motions that sent grown men sprawling. The fights usually ended with at least one man unconscious and Cornelius Blackwood $20 richer from side bets.

“Magnificent creature, isn’t he?” Cornelius would beam, accepting congratulations and whiskey from his guests. “With every penny I paid,”

creature, not man, never man,

but the exhibitions were just Sunday entertainment. Monday through Saturday, Goliath worked.

The tobacco fields of Halifax County were brutal in August. 95 degrees by 9 in the morning. Humidity so thick you could barely breathe. 50 field hands would spread across acres of waist high plants, cutting and bundling leaves under the watchful eyes of overseer Thornton.

Goliath’s job was different. While other slaves carried normal loads, maybe 40 lb of tobacco bundled on their backs, Goliath carried 300, sometimes 400. Stacks of bundled leaves piled so high on his shoulders that other slaves couldn’t see his head.

“Move faster, giant.” Thornton would shout, cracking his whip. The leather would bite into Goliath’s shoulders, adding fresh wounds to the layers of scars already there. Goliath never slowed, never complained, just moved with that steady mechanical pace, feet sinking into the mud with each step, leaving impressions 6 in deep.

By noon, when other slaves got their 15-minute water break, Goliath got 10 minutes. By evening, when others returned to the quarters, Goliath worked another hour loading the day’s harvest onto wagons, moving equipment, digging ditches that required normal slaves to work in teams of six.

At night, they locked him in the barn, separate from the other slaves. They’d welded together special chains, links as thick as a man’s wrist, attached to an iron collar that weighed 20 lb by itself. The chains were bolted to the barn’s main support beam. His food came in a trough like a horse, like a pig.

The first year Goliath ate mechanically, survival, nothing more. The second year he started to understand more English, started to comprehend the conversations happening around him. The way Cornelius Blackwood talked about him like property, like a plow or a mule. The third year something hardened inside him. His eyes, which had once held some spark of hope, became flat, dead. The other slaves noticed.

Uncle Moses, an elderly field who’d been enslaved for 60 years, watched Goliath carefully. “That one’s dangerous,” Moses whispered to the others in the quarters. “I seen that look before on Nat Turner back in 31, right before he started his rebellion.”

“Rebellion?” Young Samuel scoffed. “He barely talks. Just works and eats and sleeps.”

“That’s what makes him dangerous,” Moses replied. “He’s thinking, planning, waiting.”

“Waiting for what?”

Moses just shook his head. “Pray we never find out.”

Year four brought Dr. Artemis Witmore into Goliath’s life. Dr. Witmore was a physician from Richmond with a peculiar interest, the physiological differences between races. He’d published papers arguing that Negroes were a separate species entirely, closer to apes than to white men. His evidence came from measurements, skull sizes, bone densities, muscle compositions.

When Cornelius Blackwood mentioned his 7 foot6 slave at a gentleman’s club, Dr. Whitmore nearly spilled his brandy with excitement. “A giant negro from the Dinka region. My god, men, I must examine him. This could be the key to proving”

“for a fee. Of course,” Cornelius interrupted smoothly.

They settled on an arrangement. Dr. Whitmore would visit monthly, paying $20 per visit, plus expenses. In exchange, he could conduct non-damaging studies of Goliath’s physiology.

The first examination took place in October 1845. Goliath was chained to a wooden frame in the barn, arms spread wide, legs apart, unable to move. Dr. Whitmore circled him like a buyer inspecting livestock, measuring tape in hand, notebook at the ready.

“Remarkable. Absolutely remarkable. From toes to crown, 90 in. Arms 96 in. Skull circumference.” The doctor’s hands probed Goliath’s scalp, his face, his jaw, “pronounced brow ridge, prognatism of the jaw. All consistent with my theories about”

“can you feel pain?” Cornelius interrupted. “I mean, his skin is so thick. Sometimes I wonder if he even feels the whip.”

Dr. Witmore’s eyes lit up. “An excellent question, one we can easily test.” He reached into his medical bag and withdrew a scalpel. “This may sting a bit.”

The blade drew a line across Goliath’s forearm. 3 in long, quarter in deep. Blood welled immediately. Goliath’s jaw clenched. His eyes closed, but he didn’t scream. Didn’t even groan.

“Fascinating. No vocal response. Perhaps the pain threshold is indeed.” Dr. Whitmore made another cut. This one across the bicep. Goliath’s breathing quickened. Sweat broke out across his forehead, but still no sound.

“Remarkable restraint. Unless Unless the nervous system is genuinely different, less sensitive. We should try.”

The third cut was deeper across the chest. Blood ran in rivullets down Goliath’s torso. And then finally, a sound, low, guttural, not quite a growl, not quite a moan, something primal. Dr. Whitmore stepped back satisfied there.

“So he does feel pain. Just has extraordinary tolerance. I’ll note that in my records,” he turned to Cornelius. “Next month I’d like to examine his muscular structure more thoroughly. Perhaps some tissue samples.”

“Will it damage his ability to work?”

“Minimally, a few small incisions, nothing major.”

“Then we have an agreement.”

The examinations continued monthly for the next 2 years. Dr. Witmore would arrive with new instruments, new theories to test, new places to cut and measure and probe. He took bone samples from Goliath’s ribs, measured his lung capacity by nearly drowning him in a water trough. Tested his vision, his hearing, his reflexes, all in the name of science. All while Goliath was chained, unable to resist, unable to refuse.

And through it all, Goliath never screamed, never begged, never gave them the satisfaction. But behind those flat dead eyes, something was building. Pressure like water behind a dam. Like lava under a volcano. Something that couldn’t be contained forever.

Year seven brought Naomi. She arrived in a shipment of house slaves from South Carolina. Part of an estate sale after a plantation owner died. Small and delicate, maybe 5’2, with quick hands, perfect for sewing and cooking. Master Blackwood purchased her for $800 to help his wife manage the big house.

The first time Goliath saw Naomi, she was hanging laundry behind the big house. He was hauling timber for a new tobacco barn, a load that would require six normal men. 400 lb of oak balanced on his shoulders, their eyes met for just a moment. She looked away quickly. House slaves weren’t supposed to acknowledge field hands. Different hierarchies, different worlds.

But Goliath couldn’t look away, couldn’t stop watching as she moved gracefully between bed sheets, humming something soft and melodic. It was the humming that caught him. A tune from his childhood, a dinker song his mother used to sing.

After he deposited the timber, Goliath did something he’d never done before. He took an unnecessary route back to the barn, past the laundry lines, close enough that Naomi couldn’t help but see him. She paused mid song, stared up at him. This giant, this impossible man.

“You know that song,” he said in English, his voice rusty from disuse.

She nodded slowly. “My grandmother taught me before she was sold south. She said it was from the homeland.”

“It is.” Goliath closed his eyes, and for just a moment he wasn’t in Virginia. He was standing in the tall grass of the Nile tributaries, listening to his mother’s voice drift across the water. “It’s about the river, about home.”

When he opened his eyes, Naomi was smiling. Small and sad, but a smile nonetheless.

“I’m Naomi.”

“Goliath.”

“That’s not your real name.”

“No, but it’s the only one they let me keep.”

The relationship grew slowly, carefully. Sunday evenings, after the exhibitions, after the work, they would find each other. Sometimes just for minutes. Sometimes if they were lucky for an hour, they couldn’t touch. Not in public, not where anyone could see. How slaves who fratonized with field hands could be whipped or worse. And Goliath was too valuable an investment for Master Blackwood to allow any distractions.

But they talked in quiet corners in the brief moments between chores. Naomi taught Goliath more English, better English, the kind that let him understand not just commands, but conversations. The discussions Master Blackwood had with his sons, the letters Dr. Whitmore read aloud about his fascinating subject.

In return, Goliath taught Naomi about the homeland, the real names of things, the old gods, the way the sun looked setting over endless grassland.

“You remember it?” she asked one evening, wonder in her voice. “You were so young when you left.”

“I remember every second,” Goliath replied. His massive hands, hands that could crush skulls, gently traced patterns in the dirt. “I remember my mother’s face, my father’s laugh. The day the slavers came. I remember all of it. And I hold on to those memories like weapons.”

“Weapons.”

“One day,” he said quietly, “I will need something to fight for. Something beyond just survival. And those memories, this conversation, these are what I’ll fight for.”

In March 1853, Master Blackwood agreed to an unusual arrangement. If two slaves wanted to marry, not legally, of course, slaves couldn’t marry, but if they wanted to cohabitate, he would allow it with conditions. The conditions were simple. Both slaves had to be in his household, and any children born would be his property from birth.

Naomi approached Mistress Constance Blackwood first, asked permission, as was required. Constance looked at the tiny house slave with amusement.

“You want to marry the giant, child? He’ll break you in half.”

“No, ma’am,” Naomi replied quietly. “He’s the gentlest man I’ve ever known.”

“Gentle? Have you seen him fight?”

“I’ve seen him choose not to hurt people when he easily could. There’s a difference.”

Constant shrugged. “Ask the master. If he agrees, I won’t object. Might be interesting to see what kind of children you produce. Maybe we’ll get more giants.”

The conversation with Cornelius went similarly. He saw potential profit in breeding his most valuable slave. If Naomi produced giant children, each one could sell for thousands. If she didn’t, well, no harm done.

“You have my permission,” he told Goliath one evening. “You can move into the small cabin behind the quarters. The one we use for married couples.”

Goliath stared at him. “The chains? What about them?”

“Will I still be chained at night?”

Cornelius considered this. Goliath had been mortal slave for 12 years. Never caused trouble. Never tried to escape. The chains were really just precaution. Theater for visitors.

“Fine. No chains in the cabin. But you try to run and I’ll sell your wife to the furthest plantation I can find. Understood?”

“Understood.”

That night, for the first time in 12 years, Goliath slept without chains, with Naomi beside him, her small body pressed against his massive frame, her breathing soft and even. He lay awake for hours, one arm wrapped protectively around her, staring at the cabin ceiling.

This, he thought, this is what freedom feels like. Even in slavery, this moment is freedom.

He should have known it couldn’t last.

By 1856, Goliath and Naomi had been together for 3 years. No children yet, which frustrated Master Blackwood, but he was patient. These things took time. What Master Blackwood didn’t know was that Naomi had been using herbs to prevent pregnancy. Old knowledge passed down from her grandmother, wild carrot seeds, rue leaves. She took them every day in secret.

“I won’t bring a child into this,” she told Goliath one night. “I won’t give them another slave to sell.”

Goliath understood. But part of him, a deep aching part, wanted it anyway. Wanted a child. Wanted to hold something that was his in a world where he owned nothing.

In August 1856, the herbs stopped working. Or perhaps Naomi stopped taking them. Goliath never asked which. All he knew was that one morning she woke up and vomited and then smiled through her tears.

“I think I think I’m pregnant.”

Goliath felt something crack in his chest. Not breaking, opening like a door he’d kept locked for years suddenly swinging wide.

“Pregnant,” he repeated.

“I’m sorry. I tried to”

He kissed her gently, carefully, afraid his strength might hurt her. “Don’t apologize. Never apologize for this.”

For 3 months they kept it secret. Naomi wore loose dresses, avoided Mistress Constance’s scrutiny, but by October there was no hiding it anymore. Mistress Constance noticed first.

“Girl, are you with child?”

Naomi hesitated, then nodded.

“Well, it’s about time. The master will be pleased. Tell him at dinner tonight.”

That evening, as Naomi served roasted duck and sweet potatoes, she quietly informed Master Blackwood of her condition, his face lit up with that terrible smile Goliath had learned to dread.

“Excellent. Finally, we’ll see if you breed true to his size. If this child comes out a giant, I’ll have a breeding pair. Do you know how much that could be worth?”

From his position standing silent in the corner, Goliath felt that crack in his chest widen. Not a good feeling now. a dangerous one.

Three days later, Marcus Doyle arrived at Blackwood Plantation. Doyle was a slave trader, one of the most successful in Virginia. He specialized in specialty merchandise, the kind of slaves that attracted premium prices. Beautiful women for plantation mistresses, companions, strong men for brutal work, and occasionally pregnant women.

There was a market, Doyle explained to Cornelius over cigars and whiskey for pregnant slaves, particularly ones with interesting genetics.

“See these rich bastards in New Orleans? They’re getting bored with regular breeding programs. They want experiments, curiosities. Your giants woman, she’s what, 5′? 5’2?”

Cornelius confirmed.

“Perfect. And she’s carrying his child. That’s a scientific curiosity right there. Half giant, half normal. There are medical men in Louisiana who’d pay” Doyle paws dramatically. “$3,000 for her.”

Cornelius’s eyebrows rose. “3,000? I paid 800.”

“That was before she was carrying giant seed. Now she’s unique, one of a kind.”

“But if she produces a giant child here, I could”

“could.” Doyle interrupted. “Key word might not might come out normalsized. might not survive birth. Women that small delivering giant babies. Well, the mortality rate is high. Bird in hand, Cornelius. 3,000 in hand or maybe 5,000 in 18 months. Plus the risk.”

Cornelius swirled his whiskey. “When would you need her?”

“I’m heading back to New Orleans day after tomorrow. She’d come with me.”

“Let me think on it.”

That night, Cornelius did his calculations. 3,000 immediate versus potential 5,000 later. But that potential came with risk. If the child died, if Naomi died, he’d be out his initial investment by morning. He’d made his decision.

He found Goliath in the tobacco barn, loading cured leaves onto a wagon.

“I’ve sold your wife,” Cornelius said simply. No preamble, no sympathy.

Goliath froze. The 300B load he’d been lifting slipped from his hands, crashing to the barn floor.

“What?”

“Marcus Doyle made an excellent offer. She leaves tomorrow morning.”

“No.” The word came out strangled. “No, you can’t.”

“I can and I have. She’s my property. Goliath. Same as you. Same as that wagon. I sell what I please,”

“but the baby is also my property. Doyle’s interested in it. Wants to see if she produces a giant or not. It’s for science.”

Something must have shown in Goliath’s face. some flicker of rage that even he couldn’t suppress because Cornelius took a step back and called out, “Thorn, bring the chains.”

Overseer Thornton appeared with iron shackles, the heavy ones, the ones they used for the Sunday exhibitions.

“Just a precaution,” Cornelius said. “Until you calm down, can’t have you doing something stupid.”

They chained him, wrists, ankles connected by links thick as a man’s thumb, bolted him to the barn’s central beam. And there Goliath stood powerless as the sun set on his last evening with Naomi.

She came to him that night. Somehow she’d convinced Mistress Constance to let her say goodbye. “5 minutes,” Constance said coldly. “That’s all you get.”

Naomi ran to where Goliath stood, chained, her small hands reaching up to touch his face. He bent down, pressing his forehead against hers.

“I’m sorry,” she whispered. “I’m so sorry.”

“Don’t,” his voice cracked. “This isn’t your fault. The baby will be born free.”

He pulled back to look her in the eyes. “I swear it somehow. I will find you. I will buy your freedom.” Her child will never know chains.

Naomi was crying now, silent tears streaming down her face. “Don’t make promises you can’t keep.”

“I keep all my promises.”

“Time’s up,” Mistress Constance called.

“No, please. Just another”

“now, girl.”

Naomi pressed something into Goliath’s chained hand, a piece of cloth torn from her dress. The only thing she owned that was truly hers.

“Remember me,” she whispered.

Then she was gone, dragged away by Mistress Constance, her sobs echoing through the barn until they faded into silence.

Goliath stood alone in the darkness, chained to a beam, clutching a scrap of cloth, and something inside him, something that had been bent and compressed for 15 years, finally snapped.

Morning came. Marcus Doyle’s wagon waited outside the big house, horses stamping impatiently. They brought Naomi out in shackles, lighter ones than Goliath wore, but chains nonetheless. She was crying still, makeup smeared, eyes red and swollen.

The entire household gathered to watch. Master Blackwood, Mistress Constants, the two sons, Jacob and Nathaniel Jr. Overseer Thornton, Dr. Whitmore, who’d arrived for his monthly examination, and decided to stay for the spectacle.

And Goliath, still chained in the barn, but positioned near the door where he could see everything.

Doyle loaded Naomi into the wagon like cargo. didn’t help her climb up, just shoved her. She stumbled, caught herself on the wagon’s edge.

“You’ve made an excellent deal, Cornelius,” Doyle called out cheerfully. “I’ll write you from New Orleans. Let you know if she produces a giant or not.”

“See that you do. I’m curious.”

The wagon began to move. Naomi turned, searching the crowd until her eyes found Goliath, their gazes locked, and then she screamed. Not words, just raw animal grief. the sound of something breaking that can never be repaired.

Goliath pulled against his chains once, twice. The iron bit into his wrists, drawing blood. But the links held.

Master Blackwood laughed. “Easy there, giant. You’ll hurt yourself.”

Goliath pulled harder. The chains creaked. The wooden beam they were bolted to groaned.

“Thornton. Sedate him if you need to.”

But Goliath had stopped. He stood perfectly still, watching the wagon disappear down the long plantation road, watching until even the dust settled. When he finally turned back to face his capttors, everyone present would later swear his eyes had changed, gone flat and cold, like looking into a shark’s eyes or a snakes.

Uncle Moses, standing with the other field hands, whispered to young Samuel, “I told you. Ned Turner’s eyes looked just like that. Right before Southampton ran red with blood.”

“What’s he going to do?” Samuel whispered back.

“Something terrible,” Moses replied. “And soon.”

They kept Goliath chained for a week after Naomi left. No work, just locked in the barn with barely enough food and water to survive. Cornelius wanted to make sure the anger passed before trusting him back in the fields.

On the eighth day, Overseer Thornton came to release him. “Master says, “You can work again.” But one wrong move and you’re back in chains. Understood?”

Goliath nodded slowly.

“Good. Now come on. We’re behind on harvest because you’ve been sulking.” Thornton unlocked the shackles and stepped back quickly. Old instinct. Something felt different about the giant this morning. Something in the way he moved. Too calm. Too focused.

“Get yourself cleaned up,” Thornton ordered. “Then report to the tobacco fields.”

Goliath walked to the water trough outside the barn. washed the week’s grime off his face and arms. And as he did, he noticed something he’d never paid attention to before.

The blacksmith shop was only 30 yards away. Through the open door, he could see Josiah working the forge, emering horseshoes, and hanging on the wall just inside the entrance, tools, hammers, chisels, cutting implements, weapons.

For 15 years, Goliath had walked past that shop every day, and never once considered it. Why would he? He was property, obedient, broken.

But now, now his mind cataloged everything. The layout, the contents, the possibilities.

“Move.” Thornton cracked his whip near Goliath’s feet.

Goliath moved. But as he walked toward the tobacco fields, his eyes tracked every detail of the plantation. Things he’d never noticed or cared about before. The big house had three entrances. The front door was always locked at night, but the kitchen door, the one the house slaves used, stayed open until 1000 p.m. Overseer Thornton made his rounds every morning at 5:30, always starting at the slave quarters and moving clockwise around the property, always alone for that first hour. Master Blackwood kept a rifle in his study and a pistol in his bedroom. But he wasn’t a good shot. Goliath had overheard him complaining about missing a deer at 20 yards. The two sons, Jacob and Nathaniel Jr., slept in the east wing, second floor, windows that overlooked the tobacco barn. Dr. Whitmore visited the third Thursday of every month. Always stayed overnight. Always slept in the guest room on the first floor. The driver, Pete, a slave who’d been promoted to help manage the other field hands, had his own cabin separate from the quarters. A reward for loyalty, for betraying his own people.

Information, details, vulnerabilities. For the first time in 15 years, Goliath was planning something beyond just survival. He was planning justice.

That night, in the small cabin he’d shared with Naomi, Goliath couldn’t sleep. The space felt enormous without her, empty, haunted by memories of her laughter, her breathing, the way she’d curl against him like she was trying to disappear into his warmth. He sat on the floor. The bed was too small for him anyway, and he’d only used it because Naomi liked the softness and thought.

3 months until Naomi would give birth. 3 months until he’d never see his child. Three months of Master Blackwood profiting from their suffering.

No, the thought came clear and sharp as a knife blade. No more waiting. No more hoping. No more believing that good behavior might earn him anything other than more chains. He’d been patient for 15 years. Model slave. Perfect property. And where had it gotten him? His wife sold. His child stolen before birth. His body studied and exhibited like a circus freak.

Goliath reached under the floorboard where he’d hidden Naomi’s cloth. Pulled it out, pressed it to his face. Her scent was already fading.

“I promised you,” he whispered to the empty cabin. “I promised our child would be born free, and I [clears throat] keep my promises.”

But how? How does a slave, even a giant one, free anyone? He had no money, no connections, no power beyond his strength, unless he made power. Unless he took it, the thought should have horrified him. should have sent him running to Master Blackwood to confess his dark thoughts before they became actions.

Instead, Goliath felt something he hadn’t experienced in years. Hope. Terrible. Violent hope.

The next morning, Goliath began his preparations. Subtle things, things no one would notice. When loading timber, he took extra time near the blacksmith shop, observed Josiah’s routine, [clears throat] noted when the shop was empty, what tools hung where. When hauling water, he walked past the big house’s kitchen entrance, counted steps from the door to the main staircase. 23 steps, memorized which boards creaked. When working the tobacco fields, he positioned himself where he could see Overseer Thornton’s morning rounds, confirmed the timing, 5:30 every morning. Clockwork regular.

At meals he listened, really listened to the conversations Master Blackwood had with his sons about money troubles, about debts, about the upcoming harvest and whether it would be enough to cover expenses. Knowledge accumulated like stones. Piece by piece. Building something.

After 2 weeks, Uncle Moses approached Goliath in the fields. “You planning something?” Moses said quietly. Not a question, a statement.

Goliath kept working, not looking at the old man.

“Don’t know what you mean,”

“boy. I’m 80 years old. Been enslaved since before you were born. I know the look of a man about to do violence.”

Goliath’s hands paused on the tobacco bundle he was tying. “Then you should stay away from me.”

“Should, but won’t.” Moses glanced around, making sure no overseers were close. “You’re going to need help.”

“Why would you help me?”

“Because I’m too old to run, too old to fight. But I ain’t too old to want to see justice done. And because” Moses’s voice dropped even lower. “That man sold your pregnant wife. That’s evil even by their standards. Someone needs to pay for that.”

“If I tell you what I’m planning and we’re caught, they’ll torture me. Kill me.”

“I know.” Moses smiled, showing gaps where teeth used to be. “I’m 80 years old and been whipped more times than you got scars. Ain’t nothing they can do to me that’s worse than what I already lived through. So I’m asking again, you need help?”

Goliath looked at the old man. Really looked. Saw the decades of suffering etched into every line of his face. Saw the strength that had kept him alive through horrors Goliath couldn’t imagine.

“I need three things,” Goliath said finally. “I need to know who I can trust. I need to know the layout of the big house, every room, every exit. And I need to know when Marcus Doyle comes back.”

“Doyle, the slave trader. He comes through here every 3 months, checks on his investments. Master Blackwood mentioned he’d return in October to see if Naomi had delivered yet.”

Moses nodded slowly. “So, you planning to wait until he’s here? Kill all of them at once?”

“Yes,”

“that’s bold. That’s Nat Turner Bold. You know what happened to him? They caught him. Hanged him.”

“I know.” Goliath tied off the tobacco bundle with more force than necessary, “but he killed 57 white people first. 57. Showed the whole South that slaves could fight back. That’s what they’re really afraid of, isn’t it? Not individual escapes, not even small rebellions. They’re afraid we’ll remember we outnumber them, that together we’re stronger.”

“And you think you can make them afraid?”

“I think I can make Halifax County never sleep peacefully again.”

Moses was quiet for a long moment. Then he smiled again, a terrible, joyous expression. “All right, then. Let me tell you who you can trust.”

Over the next two months, Goliath built his coalition carefully.

Josiah the blacksmith, 30 years old, strong as an ox, with access to every metal tool and weapon on the plantation. His wife had been sold 2 years prior. He had nothing left to lose.

Ruth the midwife, 45, with knowledge of herbs and poisons that could drop a man without a mark. She delivered three babies this year, watched two of them get sold away from their mothers within weeks. Something had broken in her after the third.

Moses the coachman. Yes, he was 80, but he knew every road in Halifax County. More importantly, he knew which paths led north, which families were Quakers, where the Underground Railroad stations hid.

Samuel the field hand. Only 23, but the strongest man on the plantation after Goliath. Young enough to run after, young enough to live free.

And there was one more. Someone unexpected. Rebecca. She was a house slave. Personal maid to Mistress Constance. 18 years old, beautiful, and completely trusted by the Blackwood family, which meant she heard everything.

“Miss Constance talks like we’re not even there,” Rebecca explained during a secret meeting in Goliath’s cabin. “Just yesterday, she told Master Blackwood the guest room window latch is broken. Won’t lock properly. And Dr. Whitmore is staying in that room next week.”

Goliath nodded slowly. “Good. What else?”

“Jacob keeps a pistol under his pillow. Nathaniel Jr. doesn’t. Overseer Thornton sleeps with his door unlocked, drunk most nights by 1000 p.m. And Master Blackwood,” Rebecca’s face hardened. “Rifle in the study, loaded, pistol in his bedroom drawer. He checks both every night before bed. Paranoid, especially after what happened at the Harrison plantation.”

“What happened there?”

“Two weeks ago. Kitchen fire killed the master and his wife. Sheriff thinks it was an accident, but” Rebecca paused meaningfully. “The slaves were freed when the property was sold to pay debts.”

“Convenient accident, don’t you think?”

Uncle Moses chuckled. “There’s been three accidents like that in Virginia this year. Masters falling off horses. Mysterious poisonings. One fellow got trampled by his own cattle. We’re getting smarter is what’s happening. Learning that dead masters are free masters,”

“not free.” Goliath corrected quietly. “Dead. But yes, one leads to the other.”

He looked around at the five faces gathered in his cabin. Five people willing to risk everything.

“I need to be clear about something.” Goliath said, “This isn’t an escape plan. This is revenge. Pure and simple. I’m going to kill everyone who had a hand in selling Naomi. That means Master Blackwood, Mistress Constance, the Sons, Overseer Thornton, Dr. Whitmore, Driver Pete, and when Marcus Doyle returns him especially. Eight people.”

Samuel said “8 in one night.”

“In one night after that we run head north. Moses knows the roots but the killing comes first. That’s non-negotiable.”

Rebecca spoke up. Her voice soft but firm. “Miss Constance once slapped me so hard I couldn’t hear out of my left ear for a week. Because I put too much sugar in her tea. Too much sugar.” She looked at Goliath. “I want in. All the way in.”

“I watched Master Blackwood sell my wife.” Josiah added, “Told me I should thank him because she was difficult and now I could have a better woman. I want him dead.”

“My daughter was six when they sold her.” Ruth said quietly. “Six ripped her out of my arms, screaming. Master Blackwood’s father did that. But the sun is just as evil. I’ll help any way I can.”

Samuel and Moses just nodded.

“Then we’re agreed,” Goliath said. “October 23rd, the night of the harvest celebration. Master Blackwood always drinks heavy that night. The whole house will be drunk and careless.”

“That’s in 3 weeks,” Rebecca noted.

“Three weeks,” Goliath confirmed. “Three weeks to prepare, to gather what we need to plan every detail. Because we only get one chance at this.”

“If we fail, we die,” Moses finished. “But if we succeed, eight monsters die with us.”

“Fair trade.”

“Fair trade.” The others echoed.

The preparations were meticulous.

Josiah worked the forge every day, but certain items disappeared into hidden corners. A knife here, a small axe there, chains that had broken and needed replacing. Instead of melting them down, he hid them. Weapons, tools, anything that could be used to kill.

Ruth gathered herbs on her weekly foraging trips, oleander from the ornamental gardens, hemlock from the creek beds, gyms seeds from the fields. Nothing overtly suspicious. Midwives needed herbs for healing, but the quantities she collected were far more than medical necessity required.

Rebecca mapped the big house in her mind. Every room, every window, every squeaking floorboard. She noted Master Blackwood’s bedtime routine. Always midnight, always the same pattern. Check the doors. Check the weapons. One last glass of bourbon, then upstairs.

Moses studied the patrol patterns of the county’s slave catchers. They made rounds every 3 days, checking plantations for runaways. Their next visit would be October 21st, 2 days before the planned uprising. Perfect timing.

Samuel did what he did best, worked hard, kept his head down, and prepared his body. He was the backup. If Goliath fell, Samuel would need to finish the job.

And Goliath Goliath tested his limits. Late at night in his cabin, he would wrap his chains around his hands and pull, testing the metal, feeling where the weak points were. The chains they’d used on him for 15 years were strong, strong enough to hold normal men. But Goliath had never been normal.

On the first night of testing, he pulled until his hands bled, and the links groaned, but held.

On the fifth night, one link cracked just slightly. A hairline fracture invisible unless you knew where to look.

On the 10th night, that link snapped.

Goliath stared at the broken chain in his hands. Felt its weight, its potential. “They think metal can hold me,” he whispered to the empty cabin. “They think chains make me property. They’re about to learn different,”

he practiced with the broken chain. How to swing it for maximum impact. How to wrap it around a throat. how to use 20 pounds of iron as a weapon instead of a restraint over and over until his muscles memorized every motion until the chain became an extension of his arm.

By October 20th, 3 days before the uprising, Goliath was ready.

But fate, as always, had other plans.

Marcus Doyle arrived early. October 21st, 2 days ahead of schedule. His wagon rolled up to Blackwood Plantation at 3:00 in the afternoon, dust trailing behind it.

Goliath was in the tobacco fields when he heard the commotion. Voices raised in greeting. Master Blackwood’s booming laugh.

“Marcus, we weren’t expecting you until Thursday.”

“I know, I know, but I’ve got news about your investment. Thought you’d want to hear it in person?”

Goliath’s blood turned to ice. News about the investment about Naomi. He dropped the tobacco bundle he’d been carrying and started walking toward the big house, not running. That would draw attention, but walking with purpose, close enough to hear.

Uncle Moses saw him coming and whispered urgently, “Don’t. Whatever you’re thinking, don’t.”

But Goliath was already past, caring about caution.

He positioned himself near the big house’s front porch, pretending to work on a broken wagon wheel, close enough to hear the conversation through the open windows.

“So, what’s this news?” Master Blackwood asked.

Doyle’s voice carried clearly. “She delivered two weeks ago down in New Orleans. And dead baby still born. Little thing was well, it was deformed. Too big for her body to carry. Tore apart from the inside. The doctors tried to save it, but”

“what about the woman?”

There was a pause. A terrible heavy paw. “Didn’t make it. Bled out during delivery. I’m sorry, Cornelius. I know you were hoping for a giant breeding pair.”

Master Blackwood cursed. “Damn. Well, at least I got my 3,000 out of it.”

“Still,”

“Profit indeed. And I’ve got another proposition for you if you’re interested. There’s a plantation in Mississippi looking for specialty labor. They’ve heard about your giant. Willing to pay 8,000 if you’re willing to sell.”

Goliath stopped hearing words.

Dead. Naomi was dead. The baby, his son, his daughter. He’d never know which was dead. Gone. Everything he’d endured, everything he’d survived, everything he’d planned. And she was dead anyway.

The world seemed to tilt. Goliath’s vision narrowed to a single point, the window where Master Blackwood and Marcus Doyle were calmly discussing profit margins while announcing the death of Goliath’s family.

“Boy, boy.” Overseer Thornton’s voice cut through the fog. He was right next to Goliath now, whip in hand. “What are you doing? Get back to work.”

Goliath turned slowly, looked down at Thornton from his 7’6 height, and Thornton saw something in those eyes that made him step back, made his hand instinctively move toward the pistol at his belt.

“Now hold on!”

Goliath’s hand shot out impossibly fast for someone his size, grabbed Thornton’s throat, lifted. The overseer’s feet left the ground. His hands clawed at Goliath’s iron grip. His face went red, then purple.

“Help!” Someone screamed. “The giants gone mad,”

but Goliath was already walking. Carrying Thornton like a child carries a doll. Walking toward the big house, toward the porch where Master Blackwood and Marcus Doyle had emerged, alerted by the screaming.

“Goliath, put him down!” Master Blackwood’s voice cracked with fear.

Goliath squeezed. There was a sound like green wood snapping. Thornton’s body went limp. Goliath dropped the corpse and kept walking.

Master Blackwood fumbled for the pistol at his belt, raised it with shaking hands. “Stop. I’ll shoot. I swear I’ll”

The gun went off. The bullet caught Goliath in the shoulder, punched through muscle, broke bone. Goliath barely slowed. Master Blackwood fired again. This one hit Goliath’s chest just left of center. Goliath stumbled, dropped to one knee, but he didn’t fall. Blood ran down his torso, soaking his shirt. His breathing was labored, but when he looked up at Master Blackwood, his eyes were clear, focused, filled with a hatred so pure it seemed to physically radiate.

“You sold my wife,” Goliath said, his voice a rumble like distant thunder. “My child, for profit,”

“they were property. I can sell what I own.”

Goliath stood. The movement should have been impossible with two bullet wounds, but he stood anyway. “Then let me show you what property can do.”

He charged.

Master Blackwood emptied the pistol. Three more shots. Two missed. One hit Goliath’s leg. Didn’t matter.

Goliath hit the porch at full speed. 23 steps he’d counted before. He’d planned to sneak up them at night, silent and careful. Instead, he crashed through the front door like it was made of paper.

Inside the big house, chaos erupted.

Mistress Constance was in the parlor. She screamed when she saw Goliath. 7 ft 6 in of bleeding, furious slave smashing through her foyer.

Jacob came running from the study, rifle in hand. “What the hell?” He got the rifle halfway up before Goliath’s hand closed around his throat.

“You threw bread at my feet once,” Goliath said quietly. “Remember?”

Jacob’s eyes bulged. He tried to speak, but Goliath’s grip crushed his windpipe.

“I remember everything.” Goliath lifted Jacob off his feet and threw him. Not pushed, through. The younger man’s body sailed 15 ft across the foyer and hit the far wall with a wet crunch. He [clears throat] didn’t get up.

Mistress Constance ran for the stairs. Goliath caught her in three strides. His massive hand clamped down on her shoulder, spinning her around.

“You called my wife girl,” Goliath said. “You laughed when they took her away.”

“Please,” Constance gasped. “Please, I’m sorry. I didn’t”

“You’re not sorry. You’re scared. There’s a difference.” He grabbed her by the throat, not squeezing yet, just holding, and carried her back to the parlor, sat her down in her favorite chair, the one she’d sat in a thousand times while house slave served her tea. “Stay,” he commanded, like she was a dog.

Then he turned to hunt the others.

Nathaniel Blackwood Jr. was trying to load his rifle when Goliath found him in the upstairs hallway. His hands were shaking so badly he dropped bullets twice.

“Stay back!” Nathaniel screamed. “Stay back, Oral!”

Goliath walked toward him slowly. Inevitably,

Nathaniel pulled the trigger. “Click!” He’d forgotten to actually chamber around. “Oh, God. Oh, God, please.”

Goliath took the rifle from his hands as easily as taking a toy from a child. He examined it for a moment, then swung it like a club. The stock connected with Nathaniel’s head, bone crunched. The younger man collapsed, blood pouring from his shattered skull.

Two down. Vort to go.

Dr. Whitmore was in the guest room trying to escape through the broken window latch Rebecca had mentioned. He had one leg out when Goliath entered.

“Ah,” Goliath said softly. “The scientist,”

Dr. Whitmore froze, slowly turned to face the giant he’d cut and measured and studied for years.

“I can explain,” Witmore stammered. “I was just, it was just research, purely academic.”

“You cut me,” Goliath said “23 times. I counted each scar each time you treated me like an animal.”

“I’m sorry. I’m so so sorry.”

“No, you’re not. You’re just scared of the specimen fighting back.” Goliath grabbed Dr. Whitmore by the ankle and pulled him back through the window. The doctor hit the floor hard. The wind knocked out of him.

“Let me show you what it’s like,” Goliath continued almost conversationally. “Being studied. Being treated like you’re not human.”

He picked up the medical bag Dr. Witmore always carried, dumped its contents on the floor, scalpels, bone saws, measuring instruments.

Dr. Whitmore tried to crawl away. Goliath stepped on his leg. Not hard enough to break it, just hard enough to pin him.

“This won’t be academic,” Goliath said, picking up a scalpel. “This will be personal.”

The doctor’s screams could be heard throughout the big house. By the time Goliath finished, Dr. Artemis Witmore had 23 cuts, one for each scar he’d given Goliath. But unlike Goliath, Dr. Whitmore didn’t survive the experiment.

Outside, chaos had erupted. The other slaves had heard the gunshots. Then Goliath charged the big house and now they faced a choice. Join him or stop him.

Uncle Moses made the choice for them. He stood in the center of the slave quarters and shouted, “Tonight it’s happening tonight. Anyone who wants freedom, follow me.”

Josiah emerged from the blacksmith shop, arms full of weapons. “Who’s with us?”

20 hands went up, then 30, then 40. Within minutes, every slave on Blackwood Plantation had armed themselves with whatever they could find. Farm tools, kitchen knives, lengths of chain.

“Driver Pete!” Uncle Moses called out. “Where is he?”

“His cabin!” Someone shouted.

The mob moved as one. 40 people, unified in purpose for the first time in their lives. They found Pete trying to bar his door. Too late. Josiah kicked it open. The door exploded inward, taking Pete with it.

“Please,” Pete scrambled backward. “I was just I was just doing what I was told.”

“So are we,” Josiah said coldly.

The mob fell on Driver Pete like a wave. When they were finished, there was nothing left to identify.

Back in the big house, Goliath had found Master Cornelius Blackwood. He was in his study trying to reload his rifle with hands that wouldn’t stop shaking. Bullets rolled off the desk. His expensive whiskey had spilled, mixing with the blood that had dripped [clears throat] from Goliath’s wounds all the way up the stairs.

“Stay away,” Cornelius warned. But there was no strength in his voice. “Just terror. I’ll have you hanged, burned, drawn, and quartered.”

“You’ll be dead,” Goliath replied simply.

“I paid $4,500 for you. You’re my property.”

“I was never your property. I was just waiting.”

Goliath crossed the study in two strides, grabbed Master Blackwood by the front of his expensive shirt and lifted him off his feet.

“My wife’s name was Naomi. My child, I’ll never know if it was a son or daughter. You sold them for profit.”

“It was just business. Nothing personal.”

“It was everything personal.”

Goliath carried Master Blackwood to the window. the same window where Cornelius had stood so many times looking out over his plantation, surveying his property.

“You like the view from here,” Goliath said. “Let me give you a better one.”

He threw Master Cornelius Blackwood through the window.

The glass exploded outward. Blackwood’s body tumbled through the air, his scream cutting off abruptly when he hit the ground two stories below. The impact killed him instantly.

Goliath stood at the broken window, breathing heavily, blood running down his torso from his wounds. Below the slaves of Blackwood Plantation had gathered, 40 faces looking up at him, some frightened, some aed, all of them suddenly impossibly free.

Marcus Doyle tried to run. He’d managed to get to his wagon, was unhitching it from the post, when Goliath emerged from the big house.

“No, no, no, no, no.” Doyle fumbled with the rains, fingers slipping on leather.

Goliath walked across the yard. Each step left a bloody footprint.

“You told him she was dead,” Goliath said. “You made it sound like it was nothing, like you were discussing crop failures.”

“I’m sorry. I didn’t know you. I didn’t think.”

“No, you didn’t think. You never thought we were human enough to grieve.”

Goliath reached the wagon. Doyle tried to spur the horses forward, but Goliath grabbed the harness. The horses reared and screamed, but they couldn’t break free.

“She was pregnant,” Goliath continued. “4 months. You killed her. You killed my child.”

“It wasn’t me. The doctors, the delivery. I just arranged the”

“you sold her to people who would use her as a breeding experiment. You knew she might die. You didn’t care.”

Goliath pulled Doyle off the wagon. The slave trader fell hard, crying openly. Now,

“Please, please, I’ll pay you. I have money. $3,000. It’s yours. All of it. Just let me”

“$3,000.” Goliath repeated. “That’s what you paid for my wife’s life.” “What my child was worth?” he bent down, his massive frame looming over the cowering man. “Let me show you what your life is worth.”

Goliath’s hands found the chains attached to Doyle’s wagon. The same chains Doyle used to secure his merchandise. 20 lb of iron strong enough to hold three people. He wrapped them around Doyle’s neck.

“Please, please.”

But Goliath was done listening to white men beg. He pulled. The chains tightened. Doyle’s face went red, then purple. His hands clawed uselessly at the iron. Goliath didn’t stop until long after Doyle stopped moving.

When it was over, eight bodies lay scattered across Blackwood Plantation.

Master Cornelius Blackwood, shattered on the ground beneath his study window.

Mistress Constance Blackwood, found dead in her parlor chair. Fear stopped her heart.

Jacob Blackwood broken against a wall.

Nathaniel Blackwood Jr. skull crushed.

Overseer Thornton neck snapped.

Dr. Artemis Witmore 23 cuts too many.

Driver Pete unrecognizable after the mob finished.

Marcus Doyle strangled with his own chains.

The sun set on Halifax County, painting the sky blood red, and in the middle of it all stood Goliath, covered in wounds and blood, his own and others, surrounded by 40 freed slaves who looked at him with something between terror and reverence.

“What do we do now?” Samuel asked.

Goliath looked north toward freedom, toward the mountains where he’d heard runaways could hide. towards something beyond slavery.

“We run,” he said simply. “We find others like us, and we never stop fighting,”

Uncle Moses stepped forward. “Boy, you’re bleeding bad. Those gunshots.”

“I know.” Goliath could feel his strength fading. “Feel the blood loss catching up with him. But not yet. Not quite yet.”

“The militia will come,” Rebecca warned. “By morning, they’ll have an army hunting us.”

“Then we leave tonight.” Goliath looked around at the faces watching him. “Anyone who wants to stay, stay. Anyone who wants freedom, come with me. We head for the Blue Ridge Mountains. There are maroon communities there, places where former slaves live free.”

“That’s 300 m,” Josiah said.

“Then we better start walking.”

The exodus began at midnight. 53 slaves, every person from Blackwood Plantation, plus a few from neighboring farms who’d heard what happened and decided to take their chance, vanished into the Virginia wilderness.

They traveled by night, hid by day. Uncle Moses knew the roots, the safe houses, the Quaker families who’d hide runaways in false bottom wagons. But the journey was hard, harder than any of them imagined.

On the second night, slave catchers found their trail. Blood hounds baying in the darkness, torches moving through the trees.

Goliath turned to face them alone, told the others to keep moving.

“You [clears throat] can’t fight them all,” Ruth protested.

“I can slow them down.”

The slave catchers expected runaways to surrender. Expected them to be scared and starving and desperate. They didn’t expect a 7 foot6 giant to charge out of the darkness like a vengeful god.

The fight was brief and brutal. Three slave catchers died before the others retreated. Spooked by what they’d seen. A giant covered in blood, roaring in a language they didn’t understand, swinging a broken chain like it weighed nothing. They’d report back that the giant was possessed by demons or immune to bullets. Neither was true. But fear makes men see what they expect.

Two weeks later, the group reached the Blue Ridge Mountains. They’d lost people along the way. Four caught by patrollers. Two died from injuries. One gave up and turned back, preferring known slavery to unknown freedom. But 46 made it. 46 people who’d been property now living in a hidden community of former slaves and free blacks who’d built something impossible. A town. A real town, gardens, cabins, children playing freedom.

The elder of the community, a woman named Grace, who’d escaped 30 years prior, looked at the newcomers with knowing eyes. “You’re the ones from Blackwood Plantation,” she said. Not a question.

“We are,” Goliath confirmed.

“We heard eight dead in one night. Biggest uprising Virginia’s seen since Nat Turner. They’ve got a $15,000 bounty on you.”

“I know.”

Grace smiled. “Good. Come in. You’re safe here. For now,”

for 4 years, Goliath lived in the mountains. The community of freed slaves grew. More runaways arrived, telling stories of the giant of Virginia, of how one man had killed eight whites and led an army of slaves to freedom. The stories grew in the telling. By 1857, some versions claimed Goliath killed 20 people. By 1858, it was 30. But Goliath didn’t correct anyone. Let them tell their stories. Let the legend grow. Because legends inspired action.

All across Virginia, subtle rebellions increased. Kitchen fires that killed masters. Overseers found dead in accidents. Slaves simply walking away and never coming back. The system was cracking. And Goliath’s name, the name given to him in mockery, had become something else. A promise. A warning.

The giant could be killed. But the idea of the giant that was immortal.

October 1860. Goliath was making repairs on a cabin when the militia finally found them. 200 armed men, Virginia National Guard. They’d spent 3 years searching, following every rumor, checking every mountain hollow, and finally they’d found it. The Maroon Community.

The Elder Grace rang the warning bell. “They’re coming.”

Everyone took positions. The community had planned for this. 46 had become 80. 80 people who’ chosen death over slavery, who’d spent years preparing defenses. But 200 trained soldiers was too many.

“We can’t win this,” Josiah said quietly. He was graying now, the years in the mountains showing in his face.

“No,” Goliath agreed. “But we can make them remember.”

He turned to face the community, people he’d lived with, laughed with, helped raise children with. “Anyone who can run, run. Get deep into the mountains. They can’t catch everyone.”

“What about you?” Ruth asked.

Goliath smiled. “I’ll give you time to run.”

“That’s suicide,” Samuel protested.

“I’ve been dead since they stole me from Africa. This is just my body catching up.”

He wouldn’t hear arguments. Wouldn’t accept backup. Instead, he armed himself with what they had. A hunting rifle. Seven shots. Two pistols. 12 shots combined. And his chains. The same ones he’d broken four years ago, now polished and deadly.

Then he walked out to meet an army.

The Virginia National Guard expected a siege, expected to surround the community and starve them out. What they got instead was Goliath walking out of the treeine alone. 7′ 6 in, scarred and massive, holding a rifle like it was a toy.

Captain Morrison, leading the militia, couldn’t believe what he was seeing. “That’s him. That’s the giant everyone’s been terrified of.”

“So, we should just shoot him from here.”

“No, I want him alive for trial, for hanging. I want every slave in Virginia to see what happens to insurrectionists.”

Morrison raised his voice. “You giant, [clears throat] you’re surrounded. Surrender and we’ll guarantee you a trial.”

Goliath’s response was to raise his rifle and fire. The shot took Morrison in the shoulder, spinning him around.

“Fire, fire.”

30 rifles discharged simultaneously. Most missed. This far into the mountains, the soldiers were tired, scared, shooting at a target backlit by setting sun, but some hit. Goliath staggered as bullets punched through him, shoulder, chest, leg, side. He didn’t fall. Instead, he charged.

The Virginia National Guard had never seen anything like it. A man absorbing bullets and still running. Still fighting, Goliath crashed into the front line like a cannonball. His chains whipped out, breaking the jaw of one soldier. His rifle stock crushed another skull. His bare hands grabbed and threw and destroyed.

He was shot nine times in the first minute, 11 times in the second. But he kept fighting. A soldier later wrote in his journal, “It wasn’t human. It couldn’t be. We shot it again and again, and it just kept coming. Like killing a bear or a mountain, something too big and too angry to die.”

By the third minute, 20 soldiers were down. Dead or dying or fleeing in terror, Goliath was on his knees now. Too much blood loss, too many wounds. Even he had limits. But when a young lieutenant approached cautiously, rifle aimed at Goliath’s head, the giant reached out with one final burst of strength, grabbed the rifle barrel, bent it, then collapsed.

They shot him 14 more times to be sure, 37 bullets total, and even then it took 3 hours for him to finally die.

The Virginia National Guard dragged his body down from the mountains, displayed it in Richmond for a week. Proof that the rebellion was over, that the giant was dead. They’d hoped it would discourage further uprisings. Instead, it had the opposite effect.

Slaves across Virginia saw that giant body riddled with bullets, but still somehow defiant even in death, and learned a lesson. It takes 37 bullets to kill a freed man. and even then he dies on his feet.

Within 6 months, three more major uprisings occurred in Virginia. By 1861, the state was so destabilized that when the Civil War began, entire plantations couldn’t function. Slaves simply walked away, dared their masters to stop them.

The legend of Goliath, the 7 foot6 giant who broke his chains and killed his oppressors, spread like wildfire.

Frederick Douglas mentioned him in a speech in 1862. “They call him an animal, a monster, a murderer. But I call him what he was, a man, a man who chose death over slavery. And in choosing death, showed us all how to live.”

Today, Halifax County doesn’t talk much about Goliath. The official records call the incident a tragic slave uprising, resulting in eight deaths and substantial property damage. property damage as if humans could be property as if murder could be damage.

But in the black communities of Virginia, the story still gets told, passed down through generations, embellished and mythologized, yes, but the core truth remains.

A man stolen from Africa, displayed like a circus animal, tortured in the name of science, worked like a beast, his wife sold, his child killed before birth, and when he’d endured all he could endure, he broke his chains, killed eight men in one night, led 50 slaves to freedom, and when an army came to stop him, he stood alone and fought until his last breath.

They called him Goliath, meaning the giant who falls. But he never fell. Not really. Because even now, over 160 years later, his name is still spoken. His story still told. And every time someone hears it, really hears it, they learn the same lesson Goliath taught Halifax County that October night.

Chains can be broken, masters can bleed, and freedom is always, always worth the price.

In 1923, a historian from Howard University traveled to Halifax County doing research on slave rebellions. He interviewed descendants of people who’d been enslaved on neighboring plantations. People whose grandparents had witnessed the aftermath of that October night.

One woman, 93 years old, told him this. “My grandmother was a house slave on the Morrison place, two miles from Blackwood Plantation. she said the morning after they could see smoke rising from where the big house had been. Master Morrison gathered all his slaves, maybe 40 of us, and told us what happened. A slave named Goliath killed his master and seven others,” he said, then led a rebellion. “They’re hunting him now, and anyone who helps runaways will be hanged alongside them.” He meant it as a warning. “As fear! But my grandmother said when she looked around at the other slaves, she didn’t see fear. She saw something else. Something Master Morrison couldn’t recognize because he’d never felt it. Hope. That night, three slaves from Morrison Plantation ran, just disappeared into the darkness. Master Morrison offered rewards, sent slave catchers, threatened the ones who stayed. Nobody talked. Nobody knew anything. Within a year, five more had vanished. By 1865, when freedom finally came, only half the original slaves were still there. The rest had followed Goliath’s example. My grandmother told me that giant didn’t just kill eight white men. He killed the idea that we had to accept slavery. He showed us we could fight back, could win, could be free, even if it meant dying.”

The historian recorded her story along with dozens of others. But his manuscript was never published. too controversial, too inflammatory. The white-owned publishing houses of the 1920s weren’t interested in stories that celebrated slave rebellion. The manuscript sat in a vault at Howard University for 70 years until 1993 when a graduate student found it and finally brought those stories to light in the mountains of Virginia. The maroon community Goliath helped establish lasted until 1863. When the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, the 80 residents faced a choice. Stay in hiding or come down from the mountains into a world that suddenly, impossibly called them free.

Most chose to stay. Freedom on paper didn’t mean freedom in practice. Not in Virginia. Not in 1863. But some ventured down, tested the new reality.

Uncle Moses was one of them. He was 88 by then, ancient by any standard. He walked into the town of Halifax and stood in the center of the square, the same square where slaves had been auctioned for decades. A crowd gathered, white people uncertain and hostile. Black people amazed and terrified in equal measure.

Moses stood there for an hour. Just stood, daring someone to challenge his right to exist in that space. Nobody did.

Finally, he spoke. His voice carrying across the square. “I knew a man once, a giant 7’6 in tall, the strongest man I ever met, and the bravest. They beat him, studied him like an animal, sold his wife, killed his child, and when he’d endured all he could endure, he stood up, broke his chains, and [snorts] showed the entire South that we are not property. We are not animals. We are human beings, and human beings die free or not at all. His name was Goliath. And I watched him kill eight men in one night. Watched him lead 50 of us to freedom. Watched him stand alone against an army. They shot him 37 times before he fell. 37 bullets. And he died with his eyes open, staring north toward freedom. I’m 88 years old. I’ve been a slave for 84 of those years. And I’m standing here today free because of that man. because he taught me that freedom isn’t given, it’s taken. So to every white person hearing this, we remember. We remember every injustice, every cruelty, every family torn apart. And we will never ever forget. And to every black person hearing this, remember Goliath. Remember that one man, just one, can change everything. Can inspire hundreds. Can break a system that seemed unbreakable. They tried to erase him from history. tried to make us forget. But we don’t forget. We carry his story in our bones, in our blood, in every breath we take as free people.”

Moses collapsed halfway through his speech, exhausted, dying. They carried him to a doctor, a black doctor, one of the first in Virginia, who examined him and shook his head, his hearts giving out, worn down by years of strain. He has days, maybe hours.

Moses smiled when they told him, “Good. But I’ve lived long enough. Seen slavery end. Seen us walk free. That’s more than most of my generation got.”

He died that night peacefully in a bed instead of a field. A free man instead of property.

At his funeral over 200 black people attended. They sang spirituals, the same songs slaves had used to communicate in code, to plan escapes, to preserve hope. And they sang a new one, a song that had emerged from the mountains, from the maroon communities, from the freed people spreading across the south.

The ballad of Goliath.

It went like this. “7 ft and 6 in tall, broke his chains, and heard the call. Killed eight masters in one night, showed the southweed stand and fight. They shot him down, but he won’t fall. His spirit lives in one and all. Remember, brothers, remember well the giant who broke the gates of hell. Goliath. Goliath. Hear his name. Freedom’s price is blood and flame. Goliath. Goliath. Stand up tall when one man rises. Breaks the wall.”

The song was never written down. Couldn’t be. Literacy was still rare among freed slaves. But it didn’t need writing. It lived in voices, in memory, in the collective consciousness of a people who’d survived the unservivable. And it spread from Virginia to the Carolas, from Georgia to Mississippi, from Louisiana to Texas. Everywhere formerly enslaved people gathered. They sang about the giant who broke his chains.

In 1872, a white journalist from New York traveled south to document reconstruction. He was interviewing freed people about their experiences when he heard the song. Intrigued, he asked about its origin.

An elderly woman, formerly enslaved on a plantation in Alabama, told him, “That’s the song of Goliath, the giant from Virginia. You never heard of him?”

The journalist admitted he hadn’t.

“Well, that’s because white folks don’t want you to know. Don’t want anyone knowing what one black man did when he decided he’d had enough. Story goes like this. There was a man so tall he had to duck through doorways so strong he could carry what three men couldn’t. They bought him like you’d buy a horse. Worked him like a mule. And when they wanted entertainment, they’d make him fight three men at once. He never complained, never fought back. For 15 years, he was the perfect slave. Then they sold his pregnant wife, sold her to be a breeding experiment. She died giving birth. The baby died, too. And something in that giant just broke. He killed his master, killed his master’s wife, killed the sons, [snorts] killed the overseer, killed the doctor who’d been experimenting on him, killed the slave trader, killed eight people in one night with nothing but his bare hands and a broken chain. Then he led every slave on that plantation to freedom. 50 people into the mountains. They lived free for 4 years. Four years. while the militia hunted them. When they finally found him, he stood alone to give the others time to escape. One man against 200 soldiers. They shot him 37 times. 37. And he still killed 20 of them before he died. Now you tell me, sir, is that the action of property, of an animal, or is that the action of a man who’d rather die free than live enslaved?”

The journalist wrote the story, sent it to his New York newspaper. They refused to publish it. too inflammatory. His editor said, “The South is trying to rebuild. Stories like this will only stir up tensions.” The journalist quit his job, published the story as a pamphlet, distributed it himself. Most copies were burned. In the South by angry whites who saw it as propaganda in the North by people who wanted to move past the ugliness of slavery, but some survived. And in those survivors, Goliath’s story lived on.

At 20’s Harlem, the Harlem Renaissance was in full bloom. Black artists, writers, musicians were reclaiming their narrative, telling their own stories in their own words.

Langston Hughes heard the ballad of Goliath in a speak easy. Listened to an old man sing it with tears running down his face. Hughes sought the man out afterward. Asked about the song.

“My grandfather taught it to me,” the old man said. “He was born a slave. Freed in 1865. He told me his grandfather knew Goliath. Actually knew him. Worked alongside him in the tobacco fields of Virginia. Said Goliath wasn’t just big. He was quiet, thoughtful, would sing these songs from Africa when he thought nobody was listening. Beautiful songs, sad songs. My great greatgrandfather said everyone knew Goliath was different special. But they thought his specialness was in his size, his strength. Turned out his specialness was in his humanity. His refusal to accept what they’d made him. His determination to be a man, not property. When word spread that he’d killed his masters and freed the plantation, my great great grandfather said it was like lightning striking. Suddenly impossible seemed possible. If a giant could do it, maybe normal folks could, too. Within weeks, slaves were vanishing from plantations across Virginia. Not by hundreds, by ones and twos, but steady, constant, each one inspired by Goliath’s example. The system started cracking. And 40 years later, when the Civil War came, those cracks became chasms.”

Hughes went home and wrote a poem called Called it the Giant. It was never published in his lifetime. Too controversial, too explicitly violent. But the manuscript survived and in 1994 it was included in aostumous collection of his work. The final stanza read,

“They call him murderer. Call him beast, call him monster, call him least among the human, among the free, but I call him what he came to be. A man who said no more. A man who broke the door. A man who showed us all the way to turn the night into the day.”

In 2015, a group of historians from the University of Virginia decided to do a comprehensive study of slave rebellions in the state. They combed through court records, your property inventories, letters, diaries, newspaper accounts from the 1850s. What they found shocked them.

October 1856, Blackwood Plantation. Eight deaths in one night. Property damage estimated at 50,000 lay fortune at the time. The official record listed it as an unfortunate incident involving a mentally disturbed slave.

But the unofficial accounts, letters between plantation owners, diary entries from the period told a different story. They told of terror, of white families afraid to sleep at night, of increased security, of paranoia.

One letter from a plantation owner in neighboring county to his brother in Richmond read, “The negro uprising at Blackwoods has unsettled the entire region. Eight men dead, including Cornelius himself. The slave, a giant of impossible size, killed them all with his bare hands, then led every slave on the property to freedom. They’ve offered a reward of $15,000, the largest I’ve ever heard. But I don’t think they’ll catch him. The negroes are protecting him. Even under threat of death, they won’t talk. I’ve doubled my security. Sleep with a pistol under my pillow. Margaret wants to return to Richmond, but I can’t abandon the plantation. Not during harvest, but I confess, brother. I am afraid. If it happened at Blackwoods, it could happen here. The Negroes are watching us differently now, like they’re measuring us, calculating. I fear we’ve been sitting on a powder keg all these years and Blackwood’s giant just lit the fuse.”

The historians published their findings in 2017. The paper was titled the Blackwood uprising forgotten catalysts of the American Civil War. Their thesis was simple. The major slave rebellions everyone knew about Nat Turner Denmark Vasey Gabriel’s rebellion weren’t the only factors destabilizing the slave system. Smaller rebellions, individual acts of resistance men like Goliath who refused to accept their bondage. These accumulated, spread, inspired others. By 1860, the South was so destabilized, so paranoid, so convinced that their slaves would murder them in their beds. That secession seemed like the only option. Better to fight a war, one southern politician wrote, than to live in daily fear of our own property.

The paper won awards, was cited hundreds of times, but more importantly, it brought Goliath’s story back into the light. Mainstream history had ignored him, buried him, pretended he never existed. But he did exist, and his actions mattered, changed the course of history in ways both large and small.

In 2019, a sculptor from Richmond proposed a monument, a statue 7′ 6 in tall, cast in bronze, depicting Goliath breaking his chains. The proposal sparked immediate controversy.

“He was a murderer,” some argued. “We can’t glorify violence.”

“He was a freedom fighter,” others counted. “We can’t ignore the violence of slavery while condemning the violence of resistance.”

The debate raged for months. City council meetings, public forums, op-eds in newspapers. Finally, a compromise. The statue would be erected, but not in the city center. Instead, in the historic Jackson Ward neighborhood, traditionally black, the heart of Richmond’s African-American community.

The unveiling took place on Junth, 2021. Over 5,000 people attended. black families from across Virginia, historians, activists, descendants of people who’d been enslaved in Halifax County.

The statue was magnificent. Goliath stood tall, chains broken and falling from his wrists, face tilted upward, defiant, proud, free. At the base, an inscription

Goliath born unknown Africa. Zarka 1826 died. October 1860, Blue Ridge Mountains, Virginia. I was never your property. I was just waiting.

The crowd sang, not the national anthem, not hymns. They sang the ballad of Goliath, the song that had survived 165 years of suppression that had passed from voice to voice, generation to generation,

“7 ft and 6 in tall, broke his chains, and heard the call.”