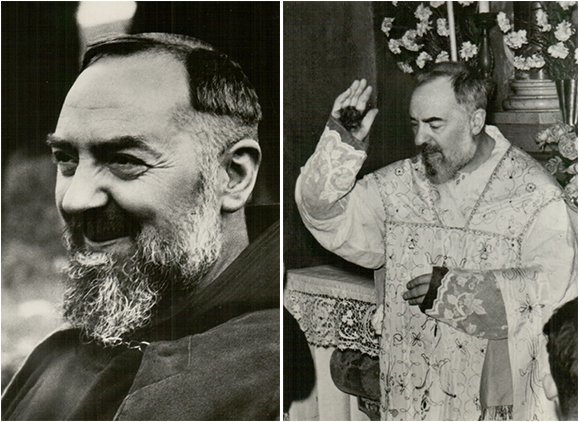

Catholic Hearts presents the extraordinary life of Padre Pio, part one.

Two world wars ravaged the 20th century. Faith was tested and doubt spread. But in a small mountain village in southern Italy, one priest would change history forever. This is the extraordinary story of Padre Pio of Pietrelcina. From his miraculous birth in 1887 to his death in 1968, 81 years of a life that defied medical science, battled demons, bore the wounds of Christ, and transformed millions of souls across the world.

You will witness supernatural visions that began at age five. Demonic attacks that left physical wounds. Medical investigations by atheist doctors who could not explain what they saw. 50 years of bleeding stigmata examined by skeptics, photographed by scientists, and witnessed by thousands. Wounds that disappeared without a scar on the day he died.

May 25th, 1887. The region of Campania in the impoverished south of Italy. The newly unified kingdom of Italy is barely 17 years old. For centuries, this peninsula was divided into rival kingdoms, duchies, and papal territories. Now they are one nation, but the south remains desperately poor. Families struggle. Children work the fields before they can read. Disease and hunger are common.

In the small medieval town of Pietrelcina, perched on a hillside in the province of Benevento, a humble family awaits the birth of their fourth child. The father, Grazio Forgione, is a farmer. The mother, Maria Giuseppa, known to all as Mama Peppa, is a woman of deep faith and quiet strength. They have little, but they have the church and they have each other.

On that spring evening, as the sun sets over the ancient stone houses, Mama Peppa goes into labor and the child is born en caul. This is a prodigious sign. The baby emerges fully enclosed in the amniotic sac, the membrane unbroken, the child wrapped in a translucent veil. It is an exceedingly rare phenomenon. In the superstitious minds of the villagers, it is both wondrous and frightening. Some say such children are marked for greatness. Others whisper darker things. The midwife carefully breaks the membrane. The baby cries. He lives.

The next morning, barely 24 hours old, the infant is carried to the church of Sant’Anna and baptized. His name: Francesco Forgione. In English, Francis, named after the great saint of Assisi.

Decades later, when Francesco is an old man and a saint himself, he weeps at the memory. He says to his spiritual children, “How ungrateful I am. For years, I never thanked God for being baptized so soon after my birth.” Even as a child, even as a saint, he sees only his unworthiness before the mercy of God.

Francesco grows up in poverty, but not in darkness. Pietrelcina is a place of stone and sky, of olive groves and ancient churches. The Forgione family owns a small farm outside the town, Acquafredda, a modest property with a simple stone house. Francesco helps his father in the fields, tending sheep, learning the rhythms of rural life. But from the beginning, the boy is different.

At age five, Francesco begins to see things that others do not. He sees Jesus. He sees the Virgin Mary. He sees his guardian angel. And he plays with him as if the angel were another child from the village. To Francesco, this is normal. He does not understand that other people do not see what he sees. He assumes everyone speaks with Jesus. Everyone walks with angels.

One day during mass at the church of Sant’Anna, the boy is kneeling in prayer when Jesus appears to him at the altar. The Lord beckons to him, calls him forward. Francesco obeys. He approaches the altar and Jesus places his hands upon the child. “Give yourself to me,” Jesus says. And the boy does. From that moment, Francesco understands, though he does not yet have the words, that his life belongs to God. His vocation begins not at adolescence, not in a seminary classroom, but here at 5 years old in a small church in a forgotten town. The seed is planted.

As Francesco grows older, his strangeness becomes more apparent. When he works in the fields with other boys, he does not behave as they do. While they joke in rough horseplay, Francesco prays. While they eat their lunch carelessly, Francesco spreads a large napkin on his lap, bows his head, and prays before taking a single bite. His friend Luigi Orlando later remembers this vividly. The other children mock him. They do not understand why he treats a simple meal with such reverence. But what disturbs them most is his reaction to blasphemy.

One afternoon, Francesco is playing with a friend, wrestling as boys do. The other boy loses and in frustration shouts a curse against God. Francesco’s reaction is immediate and total. He claps his hands over his ears, tears streaming down his face, and runs away sobbing. He cannot bear to hear the name of God blasphemed.

His mother, Mama Peppa, grows concerned. She does not know if her son is exceptionally holy or mentally disturbed. She takes him to a priest. The priest observes the boy carefully. He asks him questions. He watches him pray. Finally, he turns to Mama Peppa and smiles. “Your son is not sick. He has a great vocation.” And so, Francesco is allowed to continue his prayers, his meditations, his strange solitary hours in the *tolla*, the tower room of their house, where he kneels for hours before a small crucifix.

Even as a child, he already practices penance. He sleeps on a stone pillow. He disciplines himself. He weeps for the sins of the world. This is not a normal childhood. But Francesco Forgione is not a normal child.

When Francesco is 9 years old, his father takes him to a pilgrimage site, the sanctuary of San Pellegrino in the nearby town of Altavilla. It is a small church, modest and old, dedicated to a local saint. Grazio and Francesco kneel in prayer along with a few other pilgrims. The atmosphere is quiet, contemplative. Then a woman bursts through the door. She is screaming, sobbing, wild with grief. In her arms, she carries a child, a boy, perhaps two or three years old. But the child is horribly deformed. His limbs are twisted. His body is bent. He cannot move, cannot speak. He is alive, but barely.

The woman staggers to the statue of San Pellegrino and throws herself down before it. “Heal my son,” she cries. “St. Pellegrino, heal my son.” She begs. She pleads. Her voice echoes through the stone walls of the sanctuary. The other pilgrims watch in horror and pity. Minutes pass. Nothing happens.

The woman’s cries turn from pleading to rage. She stands, clutching her deformed child, and glares at the statue. “If you will not heal him, then take him!” And she hurls the child at the feet of the statue. In that instant, the boy is healed. His limbs straighten, his body uncurls. He stands whole and perfect and begins to walk. The sanctuary erupts in gasps and cries of astonishment. The woman collapses in tears. The pilgrims fall to their knees.

Francesco watches it all. To him, this is not shocking. This is simply what happens when you pray to the saints. This is normal. Years later, when he tells this story to his spiritual directors, they are astounded. Francesco is confused. He thinks miracles are ordinary. He assumes everyone sees such things. This is the world in which Francesco Forgione grows up. A world where the veil between heaven and earth is thin, where saints intervene, where God is close.

But as Francesco enters adolescence, something changes. He loves his family, he loves his home. The thought of leaving them, of entering a monastery, of abandoning Pietrelcina forever fills him with dread. He knows God is calling him to religious life. He has known it since he was 5 years old. But the pull of the world—not the world of sin, but the world of home, of family, of ordinary human love—is strong. He struggles. His soul is torn between two loves. The love of God and the love of his parents. This is not a battle between good and evil. This is a battle of good and better. And it costs him dearly.

Francesco begins to suffer physically. He cannot eat. He cannot sleep. His body weakens under the weight of his inner turmoil. Mama Peppa watches her son waste away. She does not understand. She suggests gently that perhaps he should not enter religious life. Perhaps he could become a diocesan priest, remain in Pietrelcina, stay close to home. Francesco’s response is heartbreaking. He says, “I no longer have a mother on earth.” He does not mean it as cruelty. He means it as truth. If even his mother asks him to compromise his vocation, then he must choose God alone.

But the struggle is not over. In the weeks before Christmas 1902, Francesco is 15 years old. He has decided to enter the Capuchin order, a strict branch of the Franciscans known for poverty, penance, and preaching. But his heart is heavy. His body is weak. He is terrified of what lies ahead. And then God intervenes.

The first vision comes just before Christmas in late December 1902. Francesco is praying, meditating on his vocation when suddenly he is no longer in his room. He finds himself in a vast open field. Beside him stands a man of extraordinary beauty, radiant as the sun. The man takes Francesco by the hand. “Come with me,” the man says. “You must fight as a valiant warrior.” Francesco does not yet know this man is Christ, but he trusts him. The man leads him across the field, and Francesco sees two groups of people. On one side stand men clothed in dazzling white robes, their faces shining with joy. On the other side stand men clothed in black, their faces twisted and dark like shadows. Between the two groups is a great empty space.

And then from the midst of that space, a figure emerges. It is a man, but not a man. It is enormous, monstrous, towering so high its head touches the clouds. Its face is hideous, blackened, the face of a demon. It strides forward and the ground shakes beneath its feet. Francesco freezes in terror.

The radiant man beside him, Christ, says calmly, “You must fight this one.” Francesco stammers, “But he is too strong. No one could defeat him.” Christ smiles. “Do not be afraid. Fight with confidence. I will always be at your side. I will help you, and if you defeat him, I will give you a crown of glory.”

Francesco has no choice. He steps forward. The battle is terrible. The demon towers over him, strikes at him with crushing blows. But every time Francesco is about to fall, Christ steadies him. Every time he falters, Christ lifts him up. And in the end, Francesco defeats the giant. The demon flees howling and the dark figures scatter in terror. The men in white—angels—erupt in joyful song praising God. Christ takes a crown of surpassing beauty and places it on Francesco’s head. Then he removes it. “I am saving an even more beautiful crown for you. But you must continue to fight. This enemy will return again and again. He will try to destroy you, but never fear. I will always be with you.”

The vision ends. Francesco finds himself back in his room, trembling, weeping. He does not fully understand what he has seen, but he knows it is important. He knows his life will be a battle.

On January 1st, 1903, Francesco receives a second vision. He has already submitted his application to enter the Capuchin order. He has been accepted. He will leave home in 5 days. But he still does not understand the first vision. What did it mean? Why did he have to fight that monstrous enemy? On this day, as he prays, a pure supernatural light floods his soul. In an instant, everything is revealed. The radiant man was Christ. The demon was Satan. The battle was not a single moment, but a symbol of Francesco’s entire life. He will fight the devil every day from now until his death. Satan will attack him without ceasing, but Christ will never abandon him. The men in white robes were angels watching and cheering for him. The men in black were demons mocking and cursing him. And the crown, the crown Christ promised is the reward waiting in heaven if Francesco remains faithful.

Now Francesco understands. His vocation is not just to be a Capuchin friar. It is to be a warrior in a lifelong spiritual battle. He is terrified, but he is also strengthened.

The night before Francesco is to leave home, January 5th, 1903, he cannot sleep. He is racked with grief. Tomorrow he will leave his mother, his father, his siblings. He will never live in this house again. He will never wake to the smell of Mama Peppa’s cooking, never hear his father’s voice in the fields. The pain is physical. He later writes that it felt as if his bones were being pulled apart. And then in the darkness, Jesus and Mary appear to him. They do not speak. They simply stand before him, radiant and serene. Jesus places his hand on his head and instantly the boy’s soul is flooded with peace. The fear remains, the sorrow remains, but beneath it there is now a foundation of unshakable strength.

The next morning, Francesco Forgione leaves Pietrelcina. He will return many times, but he will never again live as a son in his father’s house. He belongs to God now.

January 6th, 1903, the feast of the Epiphany. 15-year-old Francesco Forgione enters the Capuchin Novitiate in the town of Morcone, province of Benevento. With him are three other young men. All have been accepted. All have left their families behind. By the end of the first month, only two remain. Francesco and one other novice.

The Capuchin order is not for the faint of heart. The Capuchins are Franciscans of the strictest observance. They live in absolute poverty. They own nothing, not even books, except the Rule of St. Francis. They eat little: bread, vegetables, occasionally cheese. Meat is rare. Wine is diluted with water. They rise before dawn for prayer. They spend hours in the choir chanting the Divine Office. They work with their hands: cleaning, cooking, building, tending gardens. And they practice severe physical penance. On certain days of the week, the friars gather in the chapel, extinguish the lights, bare their backs, and scourge themselves with chains until blood flows.

This is not cruelty. This is asceticism. The intentional mortification of the flesh to free the spirit. It is a way of uniting oneself to the sufferings of Christ. For most young men from comfortable families, this life is unbearable. But Francesco was not raised in comfort. He was raised in poverty. And he has already been practicing penance since childhood. The physical hardships do not break him, but the loneliness almost does.

Novices in the Capuchin order are forbidden to speak to one another. They may speak only to the master of novices, the priest responsible for their formation. They may not converse with their fellow novices. They may not write letters home. They may not complain. This is intentional. The purpose is to strip away all human consolation, all worldly attachments and force the novice to rely entirely on God.

For Francesco, who has left behind a loving family, this silence is agony. When his mother, Mama Peppa, comes to visit him for the first time, she is shocked. Her son does not look at her. He does not smile. He responds to her questions with brief formal answers, his eyes downcast. She leaves heartbroken, thinking the monastery has turned her son into a stranger.

When Francesco’s father, Grazio, visits, having returned from working in America to see his son, he reacts with anger. He storms up to the novice master and demands an explanation. “What have you done to my son? You’ve driven him mad,” he shouts. Only then does the novice master release Francesco from his obedience to silence. The young friar immediately throws himself into his father’s arms, weeping. Grazio understands: this is not cruelty. This is formation. But it is brutal.

And yet, despite the harshness, despite the silence and the hunger and the cold stone cells, Francesco thrives spiritually. Because this life of penance has a purpose. It is not an end in itself. It is a means to union with Christ. And Francesco loves Christ with a burning, consuming love.

During the novitiate, the young men are required to meditate daily on the passion of Christ: his suffering, his crucifixion, his death. They kneel in the chapel and contemplate the gospel accounts of Good Friday. For most novices, this is a pious exercise. For Francesco, it is devastating. He weeps so violently, so copiously that the floor beneath him becomes soaked with tears. His sobs echo through the chapel. The other novices can hear him. The master of novices grows concerned. Eventually, they place a cloth beneath Francesco’s knees to absorb the flood of tears. But even the cloth is not enough. Every day after meditation, the cloth is wrung out, saturated with the tears of a boy who cannot bear the thought of Christ’s suffering.

This is not sentimentality. This is love. Francesco weeps not because he pities Jesus. He weeps because he knows that Jesus suffered for him. For Francesco, the unworthy, the sinner. And he cannot fathom such mercy. Years later, a friar finds him weeping again and asks, “Why are you crying, Pio?” “Because,” he says through his tears, “because I never thanked God for baptizing me so soon after I was born.” He is crying over an act of grace that happened when he was one day old. This is the soul of Francesco Forgione, a soul that sees only unworthiness and is overwhelmed by mercy.

January 22nd, 1904. Francesco Forgione, now 16 years old, makes his first vows as a Capuchin friar. He kneels before the altar. He renounces all personal property. He vows obedience to his superiors. He vows chastity for the rest of his life. And he receives a new name. From this day forward, he is no longer Francesco. He is Fra Pio, Friar Pious of Pietrelcina.

His mother, Mama Peppa, is present for the ceremony. When it is finished, she embraces her son and says, “You are now entirely the son of St. Francis. May he bless you.” Fra Pio will spend the rest of his life as a Capuchin friar, but he will never cease to be his mother’s son. The bond between them remains unbroken until her death.

After his first profession, Fra Pio is sent to continue his studies: philosophy, theology, rhetoric, Latin. The Capuchins do not have grand seminaries or universities. The education is modest, practical, homeschool-style instruction from older friars who serve as teachers. Fra Pio is not a brilliant student. He is not a great intellectual, but he is diligent, obedient, and pious. What marks him most during these years is not his academic success, but his continued experiences of the supernatural. He continues to see Jesus, Mary, and his guardian angel. He continues to suffer demonic attacks.

One night in September 1905, Fra Pio is in his cell when he hears footsteps in the room next door. He assumes it is his friend Fra Anastasio rising to pray. Fra Pio decides to join him. He kneels and begins his prayers. When he finishes, he leans toward the window. His cell and Anastasio’s cell are so close that the friars can pass books to each other through the windows. He calls out softly, “Fra Anastasio. Fra Anastasio.” No answer.

Fra Pio turns around. Standing in his cell is an enormous black dog. Smoke pours from its mouth. Its eyes glow with malice. Fra Pio stumbles backward and falls onto his bed. He hears a voice, not from the dog, but in the air, hissing, “It’s him. It’s him.” The dog leaps out the window and vanishes onto the roof. Later, it is discovered that Fra Anastasio was not in his cell. He was traveling. The dog was not an animal. It was the devil. This is the first of many, many demonic attacks that Fra Pio will endure for the rest of his life.

Also during these years, Fra Pio experiences his first bilocations, the mystical phenomenon in which a person appears in two places at once. One night in January 1905, Fra Pio and Fra Anastasio are praying together in the chapel. It is late, around 11:00. Suddenly, Fra Pio is no longer in the chapel. He finds himself in a rich, opulent home, a mansion far away, in a city he has never visited. A man is dying. A woman is giving birth. There is chaos, grief, and joy mingling together. Then the Blessed Virgin Mary appears beside him. She hands him a newborn baby girl and says, “I entrust this child to you. She is a rough diamond. Polish her, make her shine because one day I wish to adorn myself with her.”

Fra Pio is confused. He says, “But I am only a seminarian. How can I care for her? I don’t even know if I will become a priest. And even if I do, how can I guide her when I am so far away?” Mary smiles. “Do not doubt. She will come to you. But first, you will meet her in St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome.” The vision ends. Fra Pio is back in the chapel with Fra Anastasio. He says nothing, but he writes about it later under obedience to his spiritual director.

Years pass. Fra Pio becomes a priest. He forgets about the vision. Then in 1922, 17 years later, a young woman comes to him in confession in St. Peter’s Basilica. She is 17 years old and her name is Giovanna Rizzani. Her father died the night she was born in the city of Udine, 720 km away from where Fra Pio was praying that night in 1905. The next year, Giovanna travels to San Giovanni Rotondo to meet Padre Pio in person. When she arrives, he greets her by name. “Giovanna,” he says with a smile, “I have been waiting for you for years. Our Lady gave you to me when you were born. You belong to me.” Giovanna is stunned. She becomes one of his most devoted spiritual daughters for the rest of his life. And when Padre Pio is dying in 1968, she hears his voice, though he is far away, calling her, “Come quickly to confession or you will not find me.” She obeys. She confesses to him one last time. Days later, he dies. This is the first of Padre Pio’s spiritual children, a gift from Mary herself.

September 10th, 1910. Fra Pio is 23 years old. He has completed his studies in theology. He has received the minor orders and the subdiaconate. He has been ordained a deacon. But there is a problem. The canonical age for priestly ordination is 24. Fra Pio is still too young. However, his health is terrible. He has been sick for years. Chronic fevers, persistent coughs, weakness. The superiors believe he will not live much longer. They petition Rome for a dispensation to ordain him early so that he may die as a priest. Rome grants it.

On August 10th, 1910, in the Cathedral of Benevento, Francesco Forgione, now Padre Pio of Pietrelcina, is ordained to the priesthood. It is a small, quiet ceremony. His mother is there. His father is in America working to send money home. A few friends from Pietrelcina attend. There is no grand celebration. No one knows that this young, sickly friar will become one of the most famous priests in history.

Padre Pio celebrates his first solemn mass on August 14th in the church of Santa Maria degli Angeli in Pietrelcina. An older Capuchin friar watching him gives him a single piece of advice. “You do not have the voice to be a great preacher. Be a great confessor.” Padre Pio takes this advice to heart. For the next 58 years, he will spend 10 to 16 hours a day in the confessional, hearing the sins of millions. But first, he must suffer.

September 7th, 1910, less than 1 month after his ordination, Padre Pio is in Pietrelcina staying at his family’s small farm. His health is so poor that his superiors have excused him from living in a monastery. He has permission to remain at home, *habitu retento*: keeping the Capuchin habit but living outside the cloister. On this day he is praying under an elm tree in the family’s vineyard at Piana Romana. Suddenly Jesus and Mary appear to him. Padre Pio feels an intense burning pain in his hands. When he looks down, he sees red marks like coins on the palms of both hands. The pain is excruciating, as if nails have been driven through his flesh. He stumbles back to the house, shaking his hands as if trying to throw off something that is burning him. His mother sees him and asks, confused, “Are you practicing the guitar?” Padre Pio does not answer. He runs to his room and collapses on his bed. The marks fade after a few days, but the pain remains. This is the first manifestation of the stigmata, the wounds of Christ on the body of Padre Pio. But these wounds are invisible. No one else can see them. Only he feels the pain. And so begins 8 years of hidden suffering.

For the next several years, Padre Pio lives in a state of constant physical torment. He suffers from what doctors call galloping tuberculosis, a rapid, aggressive form of the disease that kills most patients within months. He coughs blood. He has high fevers that spike to dangerous levels. He loses weight until he looks skeletal. In 1911, his superiors send him to Naples to be examined by Dr. Antonio Cartenelli, one of Italy’s most famous physicians. Dr. Cartenelli examines Padre Pio and delivers his verdict. This man has one month to live.

The Capuchins, believing the young priest is dying, have a photograph taken of him as a keepsake. In the photo, Padre Pio is gaunt, hollow-eyed, his beard patchy and thin. He looks like a ghost. But one month passes, then another, then a year. Padre Pio does not die. But doctors are baffled. His symptoms are real: the fevers, the coughs, the weakness, but somehow, inexplicably he survives. And there is a pattern. When Padre Pio is in Pietrelcina, his health improves. When he is in a monastery, his health collapses. The superiors try sending him to different convents: Venafro, Foggia, San Marco in Lamis. Every time, within days or weeks, he becomes deathly ill. Every time they send him back to Pietrelcina and he recovers.

Eventually the superiors give up trying to move him. Padre Pio remains in his family home for 5 years, living in a kind of ecclesiastical limbo. A Capuchin priest without a community. A friar without a cloister. But God has a purpose for this isolation. During these years, Padre Pio is being prepared. He is being purified. He is being tested. And the invisible stigmata continue to torment him.

Padre Pio’s spiritual director during these years is Padre Benedetto of San Marco in Lamis, the provincial superior of the Capuchins. Padre Benedetto is a wise and holy man, and he insists that Padre Pio write to him regularly describing everything that happens: the visions, the sufferings, the mystical experiences. Padre Pio obeys, though he finds it humiliating. In these letters, we have a rare privilege. We can read the interior life of a saint as it unfolds.

On September 8th, 1911, almost exactly one year after the first wounds, Padre Pio writes: “Yesterday evening, something happened that I cannot explain or understand. In the middle of the palm of my hands, a red spot appeared about the size of a penny accompanied by a sharp and intense pain. This pain is more acute in the left hand. I also feel this pain beneath my feet. This phenomenon has been repeating itself for almost a year now, though not frequently. But I have always been overcome by a cursed shame to tell you. Only now I confess it because I have been conquered by that shame.” He is ashamed. He does not want to talk about the wounds. He does not want attention. He does not want to be seen as special. But Padre Benedetto insists on knowing everything.

In another letter, Padre Pio writes: “The pain in my hands, feet, and side is constant. It feels as though I am being pierced by swords, and the devil does not cease to appear to me in the most horrible forms, beating me in ways that are truly frightening.” The stigmata are not just physical wounds. They are accompanied by demonic assaults. Night after night, Padre Pio is attacked by demons. They appear as monstrous animals, as hideous figures, as his own deceased father to trick him. They beat him, throw him against walls, pull him from his bed. The other friars, when he briefly stays in monasteries, hear the sounds: thuds, crashes, screams. They find him bruised and bleeding. But they do not understand what is happening. Some think he is epileptic. Others think he is mentally ill. But Padre Pio knows the truth. He is in a spiritual war. And Christ is allowing it.

During these years of hidden suffering, God also grants Padre Pio extraordinary mystical gifts. One of the most astonishing is the gift of understanding foreign languages that he has never studied. In 1912, Padre Benedetto decides to test Padre Pio. He writes him a letter in ancient Greek. Padre Pio has never studied Greek. He is barely educated in Latin. He should not be able to read a single word. But when Padre Pio receives the letter, he reads it perfectly. He understands every word. He responds in Italian, explaining the content of the Greek letter with perfect accuracy.

Padre Benedetto is stunned. He writes back, “How did you read my letter?” Padre Pio’s response is simple. “You know very well. My guardian angel explained it to me.” Later, Padre Benedetto begins writing to him in French. Again, Padre Pio has never studied French. Again, he understands. And he responds in French. Padre Pio later writes, “The mission of our guardian angels is great, but the mission of my angel is even greater because he must be my teacher in the explanation of foreign languages.” This is not natural. This is supernatural. And it is a sign of what is to come.

April 7th, 1913. Good Friday morning. Padre Pio is in bed, too weak to rise, when Jesus appears to him. Jesus is sad. His face is disfigured with sorrow. He is weeping. Padre Pio asks Jesus, “Lord, why are you suffering so much?” Jesus does not answer with words. Instead, he shows Padre Pio a vision. A vast crowd of priests appears. Secular priests, religious priests, bishops, cardinals. Some are celebrating mass. Others are vesting for mass. Still others are removing their vestments after mass. Jesus looks at them with anguish. Then he turns his face away, unable to bear the sight. Two large tears roll down his cheeks. He cries out in anguish, “Butchers!”

Padre Pio is horrified. “Lord, why do you call them butchers?” Jesus turns to him and says, “My son, do not think that my agony lasted only three hours. No, because of the souls who are most favored by me, I am in agony until the end of the world. During my agony, my soul seeks a drop of human compassion. But alas, I am left alone under the weight of indifference. The ingratitude and sleep of my ministers make my agony still more bitter. Alas, how poorly they correspond to my love. What most grieves me is that they add contempt and disbelief to their indifference. How many times I was ready to destroy them if I had not been restrained by the angels and by souls who love me. Write to your spiritual father and tell him what I have shown you this morning.”

The vision ends. Padre Pio is left devastated. He writes immediately to Padre Benedetto describing everything. He adds, “This vision caused me such pain, physical and spiritual, that I was prostrate all day. I believed I would die from the suffering.” This vision reveals the heart of Padre Pio’s mission. He is not called merely to be a priest. He is called to be a victim, an offering for the sins of priests. And the invisible stigmata are the beginning of that offering.

In 1914, the world plunges into war. The Great War, later called the First World War, erupts across Europe. Millions of young men are conscripted into the armies. Trenches are dug. Cities are bombed. The death toll climbs into the millions. Italy enters the war in May 1915. And Padre Pio, like all Italian men of military age, is called to serve.

He is drafted four times between 1915 and 1918. Each time he reports for duty. Each time he becomes violently ill within days or weeks and is sent home. The military doctors examine him and conclude that he has tuberculosis. They give him medical exemptions, but each time the exemption expires, he is called back. Finally, in late 1915, they draft him and refuse to release him even though he is sick. For several months, Padre Pio serves as a soldier, though he is so weak he can barely stand. He wears the uniform. He sleeps in the barracks, but he does not fight. Eventually, the army realizes he is useless as a soldier. They discharge him permanently.

Padre Pio returns to Pietrelcina, but the war continues to rage and the superiors decide it is time to move him to a safer location, a remote monastery far from the battlefields. In 1916, Padre Pio is sent to the town of San Giovanni Rotondo, high in the mountains of Foggia province in the region of Puglia. He is told it is temporary. He will never leave.

Before Padre Pio settles permanently in San Giovanni Rotondo, there was one final chapter in his years of hidden suffering. In the nearby city of Foggia, there lives a young woman named Raffaelina Cerase. She is pious, devout, and suffers from a terminal illness: cancer. Padre Pio is assigned to be her spiritual director. He travels to Foggia regularly to visit her, hear her confession, and celebrate mass for her. Raffaelina is dying slowly. She knows it, but she bears her suffering with patience, offering it to God.

On the night of March 24th, 1916, Raffaelina’s condition worsens. Her family sends word to Padre Pio asking him to come. But Padre Pio is in his cell in the monastery resting. At exactly the moment of Raffaelina’s death, Padre Pio appears at her bedside. Though his physical body never left the monastery, Raffaelina sees him. She smiles. She dies peacefully. Later, when the friars come to Padre Pio’s cell to tell him that Raffaelina has died, he says calmly, “I know. I was there.” This is bilocation: being in two places at once. It is one of Padre Pio’s most frequently documented mystical gifts. Over the next 50 years, thousands of people will testify to seeing Padre Pio in places where his physical body could not have been. But for now, it remains a mystery known only to a few.

July 28th, 1916, Padre Pio arrives in San Giovanni Rotondo for the first time. It is a small, remote town perched on the Gargano Peninsula, surrounded by mountains and forests. The roads are poor. There is no running water. The people are desperately poor. Many of them illiterate. The Capuchin monastery, called a friary, is small and simple. There are only a handful of friars. When Padre Pio is told he will be staying here, he resists. He has heard that the people of San Giovanni Rotondo are rough, violent, even dangerous. The town has a reputation for bandits and blood feuds.

A young woman named Raffaelina Russo from the town hears of Padre Pio’s reluctance. She goes to him and says, smiling, “Father, you must come to San Giovanni Rotondo precisely because we are bandits. Come and convert us.” Padre Pio laughs, a rare thing for him, and agrees. He comes to San Giovanni Rotondo intending to stay only temporarily. He will remain there for the next 52 years until his death. And it is here that the invisible stigmata will become visible.

August 5th, 1918. The First World War is still raging, though it will end in just 3 months. Millions have died. Europe is exhausted, broken, bleeding. In the monastery of San Giovanni Rotondo, Padre Pio is hearing confessions. It is late afternoon, around 5:00. He is in the confessional with a young boy from the small school attached to the friary. Suddenly, Padre Pio is seized by an overwhelming terror. His face goes pale. His body trembles. He gasps for breath and tells the boy, “Go. I cannot continue. I feel ill.” The boy leaves, confused and frightened.

Padre Pio remains in the confessional alone. And then it happens. A celestial figure appears before him, radiant, terrible, holding in his hand a long instrument like a flaming sword. The tip of the sword glows with fire. The figure plunges the sword into Padre Pio’s heart. The pain is indescribable. It is not a physical wound. There is no blood, no visible injury. But Padre Pio feels as though his heart has been pierced through and through. As though he is being burned alive from within. He cries out in agony. He believes he is dying. This mystical phenomenon is called transverberation: the piercing of the soul by divine love. St. Teresa of Avila experienced the same thing four centuries earlier. She described it as an angel with a flaming spear piercing her heart, causing both unbearable pain and unimaginable ecstasy. For Padre Pio, there is mostly pain. The wound does not heal.

For the next two days, Padre Pio can barely move. He lies in his cell, sweating, gasping, clutching his chest. On August 7th, the pain finally subsides enough for him to rise. But he knows something has changed. God is preparing him for something greater.

September passes quietly. The war is ending. On November 11th, the armistice will be signed. The guns will fall silent. The soldiers will return home. Those who survived. But in San Giovanni Rotondo, far from the battlefields, Padre Pio is fighting a different war. He celebrates mass every morning. He hears confessions. He prays in the chapel. And the invisible stigmata continue to burn in his hands, feet, and side. But they are still invisible. No one knows. Only Padre Pio and his spiritual directors know of the wounds.

Then on the morning of September 20th, everything changes. It is a Friday morning. Padre Pio rises early as always and celebrates mass in the small chapel of the monastery. After mass, he remains kneeling before the altar to make his thanksgiving, a period of prayer and meditation after receiving Holy Communion. The other friars leave. The chapel is empty except for Padre Pio. He is kneeling in front of a large wooden crucifix. A life-sized figure of Christ, arms outstretched, head crowned with thorns. Padre Pio closes his eyes and begins to pray. And then suddenly he is no longer alone.

Padre Pio later describes what happened in a letter to his spiritual director Padre Benedetto. He writes: “On the morning of the 20th, after I had celebrated mass, I was suddenly overtaken by a drowsiness, a sweet sleep similar to a gentle rest. All of my internal and external senses, even the faculties of my soul, found themselves in an indescribable stillness. There was absolute silence around me and within me. Then suddenly I was filled with great peace and complete abandonment to God. And while all this was happening, I saw before me a mysterious figure. A person whose hands, feet, and side were dripping with blood.”

The person is Jesus Christ, crucified, wounded, bleeding. Padre Pio is terrified. He wants to cry out, to flee, but he cannot move. Christ speaks to him. “I saw him before me,” Padre Pio writes, “and he was deeply grieved by the ingratitude of men, especially those consecrated to him, those most favored by him. He said that he suffered greatly for this, and he desired to associate souls with his passion. He invited me to share in his sufferings and to meditate on them, and he asked me to work for the salvation of souls. I asked him what I could do and I heard this voice: ‘I unite you to my passion.’”

Then the vision ends. Padre Pio opens his eyes and he sees blood. His hands are bleeding. His feet are bleeding. His side is bleeding. The invisible stigmata have become visible. Padre Pio stares at his hands in horror. In the center of each palm, there is a wound, a circular open wound about the size of a coin. Blood is flowing from it, dripping onto the chapel floor. He looks at his feet. The same wounds. He touches his side. Blood seeps through his tunic. He is terrified. He is ashamed. He is overwhelmed.

He writes to Padre Benedetto: “What agony I experienced in that moment. I felt as though I was dying. I would have died if the Lord had not intervened to strengthen my heart. The vision of that person disappeared. And I realized that my hands, feet, and side were pierced and dripping with blood. Imagine my anguish. I have continued to feel it almost every hour since that day. The wound in my heart pours blood frequently, especially from Thursday evening through Saturday. Father, I am afraid I will bleed to death if the Lord does not hear the cries of my poor heart and take away these visible signs. Will Jesus grant me this grace? Will he at least remove the embarrassment and confusion caused by these outward signs?”

Padre Pio does not want the stigmata. He does not want people to see the wounds. He does not want attention. He does not want to be called holy. He begs God to take away the visible signs, not the pain, but the visibility. He writes, “I desire to be inebriated with pain, but I cannot bear these outward signs that cause me such humiliation.” But God does not remove the wounds. For the next 50 years, Padre Pio will bear the visible stigmata of Christ. And the world will never be the same.

At first, no one knows. The friary is nearly empty. The war has taken many of the friars, some to serve as chaplains, others conscripted as soldiers. Only a handful remain. Padre Pio hides the wounds as best he can. He wraps his hands in bandages. He wears fingerless gloves. He keeps his sleeves long. He does not mention the wounds to anyone except Padre Benedetto, his spiritual director. And then in October, he falls ill. The Spanish flu, the devastating pandemic that will kill between 50 and 100 million people worldwide, sweeps through Italy. Padre Pio contracts it and becomes deathly ill. He is confined to his cell for days, feverish and weak. During this time, a few people notice the blood on his bandages, but they say nothing. They think he has injured himself somehow.

It is not until mid-October, nearly a month after the stigmata appeared, that Padre Pio finally writes to Padre Benedetto and describes what happened. And even then, he begs for secrecy. “Please, father,” he writes, “do not let anyone know about this. It causes me unbearable shame.” But the secret cannot be kept forever.

Within weeks, word begins to spread. One of the friars sees the bandages soaked with blood and asks what happened. Padre Pio refuses to answer. A lay woman who helps at the friary notices the same thing. She tells her friends in the town. Slowly, quietly, the rumor spreads. Padre Pio has the stigmata.

By November, people from the surrounding villages begin to arrive at the monastery asking to see the wounded priest. Padre Pio refuses to see them. He locks himself in his cell. But the crowds grow larger. They wait outside the friary. They pray. They beg to see him, to touch him, to receive his blessing. The local bishop hears the rumors and sends a priest to investigate. The priest examines the wounds. He questions Padre Pio. He writes a report to the bishop. The bishop forwards the report to the Vatican. And the Church begins its investigation.

8 years. For eight years, Padre Pio suffered in secret, bearing the invisible wounds of Christ, enduring demonic attacks, living in isolation and illness. And now, in a single moment, everything has changed. The wounds are visible. The world is beginning to notice. Padre Pio begged God to remove the stigmata. God refused. Because these wounds are not just for Padre Pio. They are for the Church. They are for the world. In an age of war, of doubt, of skepticism and materialism, God has given the world a sign, a living reminder of the passion of Christ. But not everyone will accept it. Investigations are coming. Doctors, bishops, theologians, all will examine Padre Pio. Some will believe, others will accuse him of fraud. The battle has only just begun.

Padre Pio’s story continues. The pain, the love, the mystery, all unfold in part two. Subscribe to Catholic Hearts and walk with us in faith.

News

🎰 The Rosary Misunderstood: Why So Many Pray It Without Power—and How to Pray It Right

A mother named Clara stood before Pope Leo XIV with tears streaming down her face. Her husband was slowly dying…

🎰 The Man in White: Why Christianity Is Exploding in Iran Despite Brutal Persecution

Right now, Iran is a country where owning a Bible can lead to prison. Churches are sealed with padlocks. Pastors…

🎰 Hindu Monk Dies and Returns With a SHOCKING Message From Jesus For all Unbelievers and Believers

My name is Avind. I was once known as Swami Aravindananda. For 33 years, I lived as a Hindu monk…

🎰 When Heaven Went Dark: China, the Cross, and the Forgotten Records of History

For nearly two thousand years, historians and skeptics have posed a pointed—almost embarrassing—question to Christians: if the sky truly went…

🎰 Germany at the Threshold: A Week That May Change the Church

The week that is beginning in Germany is not like any other. Not for the Church in Germany, and not…

🎰 Afghan Pastor Sentenced To Dath By Firing Squad Miraculously Saved Few Seconds To Before Execution

Today’s testimony is shared by Rasheed, a brother from Afghanistan. A story so powerful it will shake your understanding of…

End of content

No more pages to load