While the Third Reich was collapsing and Berlin was reduced to rubble, some of the women closest to power faced that end from within.

Not as mere observers, but as figures who made decisive choices driven by loyalty, conviction, or fear.

Eva Brown returned to the capital when defeat was already inevitable.

Her presence was neither imposed nor accidental.

She chose to be there alongside Hitler until the very last moment.

She rejected any attempt at evacuation and left written evidence that she did not envision any other possible ending.

Hundreds of kilometers away, Emmy Guring faced the collapse from an Alpine residence, isolated after her husband was dismissed by direct order of Hitler.

Surrounded by constant surveillance and in a climate of growing uncertainty, she focused her efforts on protecting her daughter and trying to prevent her husband’s execution.

A threat that amid the chaos of the regime’s last days had been communicated as imminent.

This documentary examines how in the final days of the Third Reich, the wives of the main Nazi leaders did not stay on the sidelines of the collapse, but took a direct role in its outcome.

From Bhoff to the bunker, Eva Brown’s last journey.

Although her face was unknown to most Germans, Eva Brown had been by Hitler’s side for more than a decade.

She never held an official position nor appeared at public events.

Her presence remained outside the state apparatus, confined to a secondary role.

From the Burgoff residence, she lived surrounded by comforts, removed from the outside world, and devoted to her passion for photography.

However, as the Reich began to crumble, her role also began to change.

It was no longer a matter of waiting from a distance.

In November 1944, she decided to return to Berlin, not as a decorative figure, but as someone willing to accompany him until the end.

At the same time, while the Eastern Front was dissolving, and Berlin was preparing for the inevitable, Hitler left his headquarters in East Prussia for the last time.

He traveled by night aboard a special train and arrived in the capital shortly before dawn on the 21st.

Although he had initially resisted relocating, it was Martin Borman who managed to convince him.

According to Nicolas von below, Hitler already privately admitted that the war was lost, although he still did not feel ready to face his fate.

The next day, he underwent a vocal cord operation, a procedure he had known since 1935.

Joseph Gerbles described it as a minor matter, although performing it at that moment revealed his growing physical fragility.

That same day, Ava Brown quietly arrived at the chancellory and settled again in the private quarters on the second floor of the old building.

For several days, Hitler, unable to speak, communicated only in writing.

In the backyard, about 8 m underground, a reinforced shelter had already been built, the Fura bunker.

It covered just over 200 m and had 15 rooms, including a bedroom and a living room assigned to Eva.

In that winter of 1944, the couple only went down to the bunker during bombings.

The atmosphere there was damp, cramped, and poorly ventilated, very different from the environment Ava had known in Munich.

The preserved documentation does not specify the exact date when she left the city, but everything indicates she departed after only a few days without the staff or secretaries noticing.

Hitler, meanwhile, left Berlin on December 10th and headed to his military headquarters at Ziggenberg near Badnauheim.

There, his last military gamble, the Arden offensive, began to take shape.

Although he maintained appearances, in private he acknowledged that he no longer harbored hope.

Still, he kept postponing the outcome, clinging to an illusion that was rapidly fading.

After leaving Berlin in December, Hitler returned to the capital on January 16th, 1945.

2 days later, Eva Brown also returned.

This time accompanied by her pregnant sister Gretle, escorted by Martin Borman, his wife Gerder, and an SS officer.

They all traveled in a special vehicle from Bavaria, and arrived on the afternoon of the 19th.

The version claiming Ava reappeared without notice is unfounded.

In reality, she had insisted on spending the holidays at the Burgof.

But when that meeting did not materialize, Hitler arranged for both sisters to join him in Berlin.

The atmosphere at the chancellory was already grim.

Burned Fryag Von Luringhovven, a military aid, was surprised to see two women dressed elegantly walking the halls while the rest awaited instructions for the next report.

In early February, Gerbles wrote that both his wife and Ava Brown refused to leave the city.

Hitler, although not considering it prudent, expressed admiration for that decision, especially at such a critical moment.

As the Soviet encirclement tightened, Ava turned 33 in the early hours of February 6th.

By that point, they were already spending nights in the bunker, where she had prepared a bedroom with furniture brought from the chancellory.

On February 3rd, more than 900 American planes had bombed central Berlin, leaving much of the government district in ruins.

Official figures reported nearly 3,000 dead and over 100,000 homeless.

Gerbles compared accessing the furer to forcing one’s way through trenches.

Despite the rubble, the birthday celebration took place on the second floor of the old building, one of the few areas still intact.

Attendance was sparse.

Hitler, Eva, her sister, and her brother-in-law Herman Fagerline along with the Br.

Carl Brandt, although already dismissed as Hitler’s personal physician, was still part of the inner circle, but not for long.

In April, he would be arrested by direct orders from the Furer, accused of treason for reporting the Reich’s healthcare collapse and evacuating his family to Allied occupied zones.

Although sentenced to death, the execution was never carried out.

A few days after her birthday celebration, Ava Braun remained installed in the chancellory in an increasingly deteriorated environment.

Although her presence was discreet, her influence within Hitler’s inner circle had consolidated.

Martin Borman and Joseph Gerbles shared that closed nucleus.

Far from calming tensions, testimonies indicate that Brown fueled the Furer’s suspicions toward figures he did not trust.

In a letter to her friend Hera Schneijder, she described Carl Brandt’s conduct as an unforgivable betrayal, showing no compassion for someone who had been one of the regime’s closest doctors.

Even Albert Spear, until then considered untouchable, began to notice signs of distrust.

Ava Brown, acting on Hitler’s behalf, asked him about the whereabouts of his family, to which Spear responded evasively without providing concrete details.

But the question was neither casual nor innocent.

The Furer was already considering moving his closest circle to Obsaltzburg and needed to know who would truly be willing to follow him when the time came.

In that tense atmosphere, Borman privately told his wife that Ava had shown an unusually harsh tone towards some absentees during her recent celebration, suggesting that amid the collapse, she was trying to reaffirm her position in front of those who had underestimated her for years.

Nevertheless, her exact role in those decisions remain shrouded in uncertainty.

On February 9th, after spending 3 weeks in the capital, Ava Brown left Berlin, accompanied by her sister.

Borman, by Hitler’s direct order, personally handled the preparations.

That same dawn, she stayed awake until sunrise alongside the furer Albert Shpear and the architect Herman Gizler.

Gathered in the chancellor’s basement, they carefully observed the model of the future lints, the idealized city that Hitler projected as a symbol of his legacy.

From then on, visits to that model became increasingly frequent.

The Furer attended, accompanied by highranking officials like Ernst Calton Bruner, absorbed in a project that contrasted with the unstoppable advance of the enemy.

Images taken by Walter France show him aged, stooped, increasingly detached from reality while the odorfront was collapsing, and he continued talking about turning Linds into the architectural jewel of the continent as if the military collapse were not already underway.

At the beginning of February, Eva Brown briefly left the capital.

However, on March 7th, she returned to Berlin definitively.

She had already said goodbye to her surroundings in Munich, fully aware there would be no return.

Despite contradictory versions that circulated after the war, her decision to remain with Hitler did not surprise those who knew her.

The Furer himself had informed his closest collaborators that Eva wished to return, although he asked her to wait some time in Bavaria.

Finally, she returned to the capital in an all-terrain military vehicle.

The reasons for her return have given rise to multiple speculations.

Henrieta von Shiraak hinted that Eva wanted to secure a visible place in Hitler’s death.

Albert Spear described her as a premonetary symbol of the end, although his judgment is questionable.

During that period, he barely set foot in the chancellory, absorbed by his logistical responsibilities.

By midappril, the idea of a possible withdrawal to Obasaltsburg was still being considered, making any attempt to speak of definitive farewells premature.

Meanwhile, the course of the war was accelerating.

The very day Eva returned, American troops crossed the Rine and the Soviets advanced on Pomerania.

Despite everything, Hitler maintained a facade of confidence, repeating promises of miraculous counteroffensives, revolutionary weapons, and irreconcilable divisions among his enemies.

On March 19th, he signed an order authorizing the total destruction of any infrastructure useful to the enemy.

The goal was to leave behind a scorched Reich.

Only Spear’s direct intervention prevented that measure from being fully executed.

Alongside the military collapse, Hitler held long nightly meetings in the bunker that extended well into the early morning.

According to Christa Schroeda, after the reports ended, he would change tone and talk about trivialities as if refusing to accept the magnitude of what was happening.

Ava Brown, for her part, showed a disconcerting calmness.

Even in March, she organized small gatherings with secretaries in her apartment, apparently oblivious to the looming disaster.

But April marked a turning point.

In a letter dated the 19th, Eva mentioned that Soviet cannons could already be heard clearly.

Despite the warnings, she continued refusing to evacuate.

She trained daily with the weapon she carried and said she felt happy to be near Hitler.

She dressed carefully, maintained her composure, and demanded that the furer show no signs of weakness.

She even reprimanded him if she found a stain on his uniform.

Until the end, she acted as if nothing could break the world she had decided to inhabit.

On the night of April 20th, while Soviet artillery reached the southern limits of Berlin, Hitler celebrated his last birthday in the bunker.

The main leaders of the regime came to congratulate him.

Gobles, Himmler, Guring, Ribbonrop, and Spear.

One after another, they urged him to leave the city and seek refuge at the Obazaltzburg.

For moments, he seemed to consider the idea.

He even ordered the evacuation of his secretaries, assuring them he would meet with them again in a few days.

Shortly afterward, Ava Brown once again organized an impromptu celebration in her rooms at the Chancellory.

She invited those nearby, secretaries, officers, even Martin Borman.

Amidst drinks, old music, and forced cheerfulness, they tried to dispel the growing fear.

At dawn, central Berlin was already under enemy fire.

As hours passed, the pressure increased.

Ribbentrop approached Ava to ask her to try to persuade Hitler to leave.

She was categorical.

If he decided to stay, she would stay as well.

Meanwhile, the Furer ordered a desperate offensive with improvised units.

His mental balance deteriorated rapidly.

He feared being sedated and forcibly evacuated, so he forbade his personal doctor from coming near, expelling him from the bunker along with AA’s jewels.

On the morning of April 22nd, the news that Steiner’s counterattack had not occurred, triggered a crisis in the bunker.

Hitler, visibly upset, shouted uncontrollably for half an hour and declared that all was lost.

Amid the collapse, he gave the order to evacuate the complex, but Ava rejected the idea with determined tenderness.

Facing his officers, he responded by kissing her on the lips.

No one dared to move.

Hours later, Eva retired to her rooms and wrote a brief letter to her friend Hera.

She acknowledged that the end was near and stated she was not afraid to die as she had lived.

However, she left a small window open to doubt, asking her to keep the letter until we know our fate.

This intimate farewell was followed by another, this time addressed to her sister Gretle.

Ava spoke of a minimal hope, although she made it clear that they would not allow themselves to be captured alive.

She took the opportunity to put her personal affairs in order and gave precise instructions.

Destroy all her correspondence except for Hitler’s letters.

Even in those final hours, she continued smiling, toasting with champagne, and demanding from those around her the same absolute loyalty that she offered unconditionally.

As the days passed, and the roar of bombings relentlessly shook the bunker, the tension among those still remaining became completely unbearable.

Ava Brown remained steadfast beside Hitler when he began distributing poison capsules among his close circle.

The instructions were direct.

The end had to be swift and leave no room for enemy intervention.

The compound, far from being potassium cyanide, as many had imagined, was pric acid, a colorless liquid that caused death within seconds and left a penetrating smell of bitter almonds.

During the nightly meetings in Hitler’s lounge, the only topic was now the end.

Ava, with contained coldness, stated she wanted to die like a beautiful corpse.

He, for his part, explained that he would shoot himself in the temple and then order his body to be burned.

The conversations grew darker by the day.

Some drank non-stop.

Others, like Eva and Magda Gerbles, walked the halls smoking and speaking in low voices.

The atmosphere swung between dejection and forced calm.

On April 28th, a report from London marked a decisive turning point.

The Reuters agency announced that Hinrich Himmler, head of the SS, had offered unconditional surrender to the British and Americans behind Hitler’s back.

Mediation had been underway for weeks through Count Folk Bernardot of the Swedish Red Cross committee.

The betrayal by one of his most loyal collaborators unleashed uncontrollable fury in Hitler.

By then, Herman Fageline, Ava Brown’s brother-in-law and a trusted man in the inner circle, had disappeared.

She herself had written to her sister that he had left for now and to organize a unit and that he would likely survive, but the facts indicated otherwise.

Fageline had tried to escape and had called Ava suggesting she leave Berlin.

In Hitler’s eyes, this was treason.

He was captured shortly afterward, dressed in civilian clothes, hiding in his private apartment.

Interrogated at the Chancellery and found guilty of desertion, he was executed that same April 28th.

The capital was already in ruins.

Hitler and Ava Brown then began silently preparing their final act.

After Fageline’s execution and the news of Himmler’s betrayal, Ava Brown and Hitler made a final decision to get married.

The ceremony was organized quickly and discreetly in an atmosphere marked by total collapse.

Only a handful of people were informed beforehand.

Joseph Gerbles, Martin Borman, Nicolas Fonbelo and the secretary Troudel Junga to whom Hitler dictated his political and personal testament that very night.

In the document, Hitler justified the union by stating that after years of struggle, he was finally marrying the woman he had chosen to share his fate in the besieged capital.

He noted that by dying together, they reclaimed what their public life had denied them.

But the tone of the text left more questions than answers.

No emotions or words of affection toward Ava Brown were revealed.

The content was solemn, almost bureaucratic.

The wedding took place between the night of April 28th and the early hours of April 29th.

The civil officer, Walter Wagner, was summoned in haste.

Gerbles and Borman signed as witnesses.

After the ceremony, there was a brief champagne gathering in the bunker’s living room.

Among those present were Magda Gerbles, Generals Krebs and Burgdorf, Gerdera Christian, Constansa Manzi and Arur Axman.

According to von Below, a collective effort was made to evoke the good times, although the atmosphere was gloomy and artificial.

On the afternoon of the 29th, Hitler ordered the poison to be tested on his dog, Blondie.

The death was instantaneous.

Later, the judicial authorities in Burka’s garden concluded that it was a preliminary test before Eva Hitler’s final decision, which had already been made by that time.

By then, telephone lines to the outside world had been completely cut off.

On April 30th, Soviet troops reached the outskirts of the Reichd.

Shortly after 3:00 in the afternoon on April 30th, Hitler and Eva withdrew to their rooms.

In silence, she bit into the cyanide capsule.

He followed suit and as the poison began to take effect, he shot himself in the temple.

Their bodies were taken to the chancellory garden, dowsted with gasoline and set on fire as he had ordered.

That same night, the remains were buried in a crater opened by a bomb during the last bombings.

Fanaticism to the end, Magna Gerbal’s final decision.

Long before the bodies of Hitler and Ava Brown burned in the chancellory garden, Magda Gerbles and her six children still lived at the country estate in Lanca, a peaceful environment that seemed detached from the imminent collapse of the Third Reich.

It was the summer of 1944.

In that place, removed from the front and the noise of bombed cities, the war seemed a distant reality, provided one avoided newspapers and the radio.

For the children, those months were calm.

Helga, the eldest, was approaching 13 years old.

Intelligent and perceptive, she sensed the adults unease, although no one explained anything to her.

Her younger siblings lived in a world of family routines, outdoor play, and lessons with the governness chosen by Magda from dozens of candidates.

This discreet and loyal woman would recall years later that coexistence without resorting to political judgments or superficial anecdotes.

The Gerbal’s children were described as kind, balanced, and well-mannered.

Helmut, the only boy, stood out for his introspective character.

His father, however, expected a firmer, less docsile attitude from him.

When a school report warned about his poor performance, the atmosphere became tense.

Joseph Gerbles reacted harshly.

It was then that Magda took charge, supported by the governors.

They devoted daily hours to Little Helmet, and after a few weeks, not only did he improve, but he earned unexpectedly high grades.

Despite his central role in the regime’s propaganda machinery, Gerbles showed himself at home as an enthusiastic father, sometimes provocative.

He sought to awaken in his children a rebelliousness that never came.

He often made absurd comments to see if anyone would contradict him.

On one occasion, he managed to disturb the atmosphere so much that the children chased him around the room.

Helmet hiding under a sofa made him trip.

Everyone laughed except him.

Wounded in his pride, he lost control.

But when the governness confronted him, he changed his attitude.

He admitted his mistake and promised to make it up to the boy.

Magda, for her part, maintained her composure.

Even as the Reich’s situation deteriorated, she kept a friendly demeanor with the staff.

Only in private did she show signs of exhaustion.

At irregular intervals she had episodes of domestic frenzy.

She would remove curtains, empty furniture, and reorganize every corner, as if by ordering her surroundings, she could resist the chaos that was slowly approaching.

During the last months of 1944, Magda Gerbles divided her time between the family estate in Lanca and brief trips to Berlin.

Whenever Joseph required her, she went without hesitation.

Neither low-flying aircraft nor the poor state of the roads could dissuade her.

Although the strain in their relationship was evident, she still felt instinctively connected to him.

Life in Lanka retained a certain routine.

Hitler no longer visited the property, but Eloqua, her closest friend, appeared with increasing frequency.

Only with her did Magda speak without filters.

Her mother, Fraend, had also settled there.

Although the coexistence became tense, overwhelmed by fear, the elderly woman vented her anguish on her daughter, demanding impossible solutions.

She sometimes burst in at dawn, hinting at desperate gestures.

Although she did not carry them out, her words left a lasting impression.

Years later, she would recall Magda affectionately, but would not find a single kind word for her son-in-law.

On her birthday night, the children entered her room dressed in party clothes and carrying handmade gifts.

Magda, surprised, broke down in tears.

No one yet spoke of the outcome.

One of the attendants recalled that in moments of discouragement, Magda mentioned an end, though never clearly.

She still trusted that something unexpected might change everything.

Her habit was to wait and decide only when no options remained.

The children stayed in Lanki until late January.

Columns of displaced people multiplied and Helga, the eldest, began asking questions that no one wanted to answer.

Shortly afterward, Joseph ordered the move to Schwanver.

The caravan left at night along dark and congested roads heading toward the banks of the Harl.

For a few weeks, the war seemed to fade into the background.

Spring was blooming in the gardens.

The river water sparkled in the sun, and the explosions, though present, still sounded far away.

However, from the east, artillery began to dominate the landscape.

When the children asked about the loud noises, Magda responded calmly, assuring them that everything would pass soon.

On April 18th, she called from the bunker and gave the order to bring the children back to Berlin.

The roots barely offered any way out, and the city hardly provided any shelter, but the journey was carried out nonetheless.

Amid improvised suitcases and restrained farewells, the family began their last move while the calm gradually gave way to the siege tightening around the capital.

In the days following the move to Berlin, the situation in the bunker became increasingly unbearable.

On April 25th, Hitler offered Magda Gerbles and her children the possibility of leaving the capital.

The window to escape was minimal, but still existed, and the Furer insisted they should save themselves.

Magda without hesitation rejected the offer.

She said her decision was already made that they would stay there with him until the end.

That same day, Eric Kempka, in charge of the Chancellory vehicle fleet, tried again.

He gathered several armored cars and went to Magda to beg her to take the last chance.

He planned to evacuate her to Gateau, where a plane awaited with engines running.

For a moment, she seemed to hesitate.

According to Kempka himself, she even let out a sigh of relief, as if allowing herself for a second to consider escape.

But the silent presence of Joseph Gerbles, who had overheard the conversation, changed the course.

He reminded his wife that although she and the children were free to leave, he would stay until the end.

Magda, immediately regaining her composure, politely declined the offer.

“The children and I are staying too, Mr. Kempka, but thank you.”

Not long after, the presence of aviator Hannah Reich briefly disrupted the bunker’s routine.

She had arrived after completing a risky flight, and it was Magda who led her to her room, where six pairs of eyes watched her curiously from their bunks.

The children, fascinated by the figure of a pilot, began to ask questions relentlessly.

Amid the bombings, Reich answered with stories, taught Tyrion songs, and shared tales to help them fall asleep.

Despite the confinement and the chaos outside, they maintained an unexpected joy, protecting each other with natural tenderness.

However, beneath that surface of normaly, tension continued to rise.

For Reich, those scenes so serene in the face of collapse became an emotional burden difficult to bear.

Throughout those days, Joseph Gerbles became increasingly convinced of the outcome.

He knew defeat was irreversible and despised attempts by figures like Himmler or Guring to negotiate with the allies as he did not consider surrender a possibility.

Becoming his own director, he sought to give his death a symbolic dimension as if it were a final propaganda operation conceived even beyond the end.

Magda, for her part, made the decision on her own without being prompted.

Joseph, who always had considerable influence over her, could have persuaded her to leave, but chose not to.

According to some testimonies, they had agreed on their common fate weeks earlier, perhaps since March, when the regime’s collapse was already inevitable.

A spiritual background also played a role in that decision.

Magda believed in reincarnation and conceived death as a transition to another form of existence.

This view, based on a personal interpretation of Buddhism, seems to have served as her intimate justification.

The children’s governness recalled that philosophical inclination, and although Magda never expressed it as a formal doctrine, it served to explain what otherwise seemed inexplicable.

Years earlier, Magda had confessed to Eloquant a disturbing thought.

She said she wanted to offer her children a new chance, but in another plane, and to achieve that, they would first have to die.

The decision was made.

Yseph Gerbles did not contemplate life after Hitler’s fall.

Magda, as she had already made clear, did not intend to separate from her husband, nor allow her children to grow up in a world where the regime to which they had dedicated their existence ceased to exist.

On the afternoon of April 29th, Gerbles wrote a final document.

It was not addressed to the present, but to the future.

In it, he declared that for the first time in his life, he would disobey a Furer order.

He would not leave Berlin.

He expressed that his wife and children shared that decision and that doing otherwise would make him a traitor to himself and to the people.

He stated that dying with Hitler was the most dignified way to serve Germany and that in times to come examples would have more power than men.

Therefore, he concluded the entire family would remain in the capital until the end.

While Gerbles maintained his activity alongside Hitler, Magda spent her last days almost entirely in the family bunker.

She barely left.

She took care of household tasks, washed clothes, cooked for the children, and mended garments.

Time, which at some point she had thought scarce, stretched unexpectedly, and with it the emotional burden of what she knew was approaching.

The children consequently began to show signs of unease.

The Soviet bombing was growing more intense, and the trembling ground made it impossible to ignore what was happening outside.

Helga, the eldest, asked her mother if they were really going to die.

Magda responded with vague phrases, assuring her that the sounds were a sign that German soldiers were coming to rescue them.

But her subdued tone no longer convinced the girl.

Even so, everyday life continued inside the bunker.

Each of the children had brought with them only one toy.

They played in the hallways, followed their mother through the corridors, and once a day went to greet Hitler and pet his dog, Blondie.

That small ritual served to maintain the illusion that everything was still in order.

To the eyes of those who observed them, Magda’s children maintained a disconcerting calm.

They were polite, attentive, and perfectly dressed.

Even in that environment, they made a deep impression.

Some soldiers, hardened by years of war, silently wondered why those children, so detached from everything, were not sent to a safe place.

Beneath the constant roar of the Soviet siege, the Gerbal’s palace was dismantled piece by piece on the surface. what the bombs had not taken.

Servants and soldiers removed, crossing ruins or tunnels with everything they could carry.

Neither the park surrounding the residence nor the paintings stored in underground shelters were preserved.

Other family properties such as Lanca or Schwan and Verda were already in Soviet hands, and in both places the luxury had disappeared without a trace.

In that same environment of material and symbolic decay, the last acts of Joseph and Magda took place.

On April 28th, Hitler announced his decision to take his own life and invited those present to follow his example.

Joseph Gerbles was one of the few who did not hesitate.

That night, he witnessed Hitler’s marriage to Eva Brown as a symbolic closure of a mutual loyalty begun years before when Hitler had been godfather at the Gerbal’s wedding.

On April 29th, Hitler appointed Gerbal’s chancellor of the Reich.

Practically, that title no longer meant anything.

Symbolically for Joseph, it was the peak of his career.

Not only was he the last of the regime’s founders still standing, but also the only one Hitler had kept in his intimate circle until the end.

His death, planned as a propaganda act, was meant to reinforce that image, that of a man who did not surrender, even in defeat.

The following morning, while Hitler said goodbye one by one to his collaborators, he made an unexpected gesture.

When shaking Magda Gerbal’s hand, he removed the golden party badge from his jacket and pinned it on hers, and she, always composed, broke into tears.

Although her faith in Hitler had eroded over time, that act sealed a bond that, for her still held a transcendent dimension.

Hours later, Adolf and Eva would disappear.

Joseph and Magda along with their children remained waiting, isolated in their private bunker with no witnesses but the concrete walls and the distant echo of a lost war.

After Hitler’s final gesture toward Magda, which had moved her to tears, she focused on writing one last letter to her eldest son Harold, entrusting it to aviator Hannah Reich.

In the letter written from the confinement of the bunker, she justified her decision and Joseph’s as the only possible outcome for their lives within the national socialist ideal.

She stated that Hitler had tried to persuade her to leave, but she had not even considered it.

She said that with the regime’s fall, everything that had value in her life had also collapsed.

Beauty, nobility, fidelity.

That is why she had taken the children with her.

Convinced that the coming world would not offer them a dignified life, she asked her son never to forget his origins, to live with honor, and that his own conduct give meaning to the sacrifice they were about to make.

She proudly described the maturity of the children who endured confinement without complaint, consoling one another when explosions shook the bunker.

She even recounted that amid the collapse, the children still managed to draw a smile from the furer and told with special emotion how he had pinned his golden party badge on her jacket, a gesture she interpreted as the greatest possible recognition.

A few hours later, the six Gerbal’s children were killed inside the shelter.

No words were heard when Magda left that room arm-in- arm with her husband.

Her face was sunken, her eyes red, and her body bent.

Even so, she maintained a disconcerting calm, as if the weight of duty outweighed that of pain.

On the night of May 1st, when the final escape attempt was being organized, Joseph and Magda slowly ascended the concrete stairs toward the outer garden.

They would not allow anyone to help them.

At the bunker’s exit, their driver and Captain Schwagaman awaited them.

To one side rested the fuel cans.

They crossed silently into the darkness, stopped a few meters away.

A sharp shot broke the stillness.

Joseph had shot himself.

Magda beside him fell after biting a poison capsule.

The other confinement, Emmy Guring and the end of Karenhal.

While the last death packs were being sealed in Berlin, in the south of the country, Emmy Guring lived a completely different day.

On April 21st, 1945, amid a dense rain that hid the mountains, she anxiously awaited her husband’s return.

Herman, then still commander of the Luftvafer, had gone to the eastern front very near Karinhal.

That night, without warning, her sister burst excitedly into the room.

Hermon had returned.

She greeted him with relief and affection, and together they went to see their daughter, Ed, who slept unaware of the gravity of the moment.

That brief family moment failed to conceal the tension already etched on Guring’s face.

He recounted his journey through a devastated Germany with columns attacked from the air and cities reduced to ruins.

Hitler had sent him to Burus garden expecting to reunite there.

However, doubts about the immediate future were evident.

On the 23rd, upon unexpectedly returning to his room, Herman carried a message from Berlin.

General Ker had arrived with momentous news.

In a meeting held in the bunker, Hitler had admitted that the war was lost and before his generals had uttered an ambiguous phrase suggesting that Guring negotiate with the Allies.

Clinging to the legality of the June 1941 decree that named him as Hitler’s successor in case of incapacity, Herman decided to write to Hitler requesting permission to assume command.

If he did not receive a response before 10:00 at night, he would act on his own.

That very afternoon, a reply arrived.

The decree was no longer valid and Hitler expressly forbade any initiative.

Shortly thereafter, several SS men arrived at Guring’s residence.

With disbelief, Herman assumed it must be a mistake.

However, he was placed under house arrest, cut off from communication, and watched throughout the night.

Emmy, locked in her room, sensed that something irreparable was happening.

The hours passed slowly, surrounded by armed soldiers.

Although they managed to dine together, the tension was such that no one touched their plates.

The next day, a guard informed her that she would never see her husband again.

The isolation had just begun.

The confinement imposed by the SS only intensified the gravity of what had occurred.

Emmy could barely spend a few minutes with her husband, who was beginning to accept that he no longer had control over his fate.

The night passed amid the alarms of bombings, and at dawn, a loyal officer allowed her a brief reunion with Herman, she assured him that Eda suspected nothing.

Relieved, he grasped her hand, repeating in disbelief that all this was unthinkable.

Minutes later, the alarm sounded again.

Emmy ran to her daughter’s room, but the girl had already been taken to the shelter.

Searching for Herman, she found him shaving calmly.

He refused to go down to the basement, but finally gave in to Emy’s insistence.

Together, they were led to the house seller, where Eda awaited them.

The official shelter built by Order of Borman was not yet operational, and the cellar door, deformed by impacts, could not close completely.

During the wait, trembling, Eda commented that the attack was especially intense.

Her father took her in his arms and told her that as long as they were together, she should not be afraid.

Emmy, silent, wished for a direct hit to end everything at once, but it did not happen.

The explosion ceased, and minutes later, an officer allowed them to enter the large shelter where they reunited with the staff with whom they had shared years of palace life.

In that improvised space, Emmy recalled the days of prosperity.

She even tried to retrieve the gray scarf that Eda had knitted for her father, but only found shreds among the debris.

Some servants managed to rescue mattresses and blankets to improvise beds.

It was in that atmosphere, suspended between collapse and routine, that an unexpected scene occurred.

Edda, still unaware of the magnitude of the moment, asked if it was true that Hitler had betrayed her father.

Observed by SS members, Emmy simply promised her that one day, when everything returned to normal, she would explain the truth.

Later, confirmation came of what until then had been only rumors.

Hitler accused Guring of high treason.

Although they were later informed he would not be executed, he would lose all his positions and be expelled from the party.

The news was devastating.

Desperate, Emmy begged the doctor to delay, sending a distressing message that Herman had dictated.

There was no mercy.

The response arrived a few hours later.

She, her husband, and her daughter would be executed along with everyone present.

The threat hung over Herman like a sentence already passed.

Emmy could not accept that Hitler had ordered his death and much less that of their daughter.

However, one detail sparked suspicion of manipulation.

In the original message, someone had reinserted a phrase that Guring had removed.

Even so, the threat was real.

According to the orders, the execution would not take place until after the fall of Berlin.

When informed that Elsa, Robert, and Christa would be excluded from the sentence, the three servants reacted with loyalty that exceeded any protocol.

They demanded to be executed alongside their masters if they were condemned.

The gesture, unexpected and profound, left Guring speechless.

He could only say that there were still moments capable of giving meaning to a life.

Shortly after, they were informed they would be transferred to Mountorf Castle in the Austrian Alps.

Emmy knew that place well, an old family residence of her husband, gloomy, with endless corridors and a reputation for being haunted.

She accepted the transfer on one firm condition.

She would not be separated from Herman.

Her insistence worked, and she was able to travel with him.

In Mountainorf, Emmy experienced unexpected relief.

Breathing fresh air after so many days of confinement restored some serenity, although the danger had not disappeared.

One night, her sister discovered an underground passage connecting to the village.

Taking advantage of the lack of surveillance, they managed to contact Luftvafa officers who, pretending to have authority, convinced the SS to disobey the execution order.

The immediate threat seemed to dissipate, though not entirely.

On May 1st, a hidden radio brought them the definitive news.

Hitler had died.

Deprived of any possibility to justify his position before him, Guring fell into a state of absolute despair.

Emmy, trying to pull him away from his desperation, pretended to feel unwell.

The effect was immediate, and he refocused on her.

Days later, on May 7th, the message they had been waiting for arrived.

They were free.

But for Emmy, that freedom brought no comfort.

Guring, steadfast until the end, wrote a final letter addressed to Eisenhower.

In it, he did not ask for mercy, only one thing, that Germany might find a dignified peace before being completely destroyed.

The next day they set off for Zelc, crossing the snowy landscapes of the Lunga with uncertainty marking every kilometer.

Emmy and Herman Guring trusted that the American forces would allow them to surrender without resistance.

Shortly before arriving, the echo of gunfire broke the Alpine silence.

They thought it was the Americans, but it was only German soldiers spending their last ammunition.

Upon reaching Rajtart, Luftvafa units surrounded the car upon recognizing the rice marshal.

It was a brief scene charged with emotion where the enthusiasm of the troops contrasted with Herman’s somber face.

Shortly afterward, an American vehicle approached.

An officer emerged who introduced himself as Stack.

He maintained protocol, showed respect, and communicated to Emmy a message that reassured her.

Eisenhower accepted receiving Guring, who could come and return in freedom.

With that promise, they were housed in Fishhorn Castle.

That very night, an American soldier spoke to Emmy the word she had been waiting for years to hear.

The war was over.

Overwhelmed with emotion.

She cried with relief for the first time in a long while.

The next morning, while Herman prepared for his meeting with Stack, Emmy firmly reminded him that whatever happened, she would not separate from him.

He tried to appear optimistic, although his gestures hinted that this was a different kind of farewell.

From the window, she saw him leave for the last time as a free man.

Moments after seeing Herman depart, Emy’s body reacted unexpectedly.

Her right arm became paralyzed for no apparent reason.

She did not yet know it would take 2 years before she recovered movement.

At that very moment, Eda entered the room.

The girl, unaware of everything except the change in tone around her, asked a question as simple as it was devastating.

She wanted to know if they had won the war.

True to her promise not to lie, Emmy answered honestly.

Ed, still confused, nodded determinedly and said she would be brave, although she could not hide her disappointment.

She had expected Germany to win.

As the days passed, the apparent calm gave way to a routine marked by confusion.

Constant searches, unfounded suspicions, and baseless accusations became part of daily life.

A misunderstanding with a young actress surnamed Brawn led a general to suspect that Emmy was hiding information about her relationship with Ava Brawn.

The disdain she received from that officer, convinced of a non-existent lie, left a difficult to erase scar.

On June 2nd, Eda turned seven.

Emmy tried to offer her some comfort, some gesture, but sadness permeated everything.

A few days earlier, Frabala, devastated by her husband’s arrest, had taken her own life.

Without knowing it, Emmy was right when she told her daughter that her aunt had reunited with her husband.

In that shattered world, even the simplest words contained truths impossible to accept.

After weeks of uncertain waiting, the routine in Strabing became increasingly bleak.

The absence of news about Herman fed a growing unease, and isolation weighed heavier than any concrete suspicion.

Amid that tense stillness in mid-occtober of 1946, an acquaintance approached with the information Emmy had so feared receiving.

Her husband had taken his own life in his Nuremberg cell a few hours before the scheduled execution.

There was no official announcement, nor immediate confirmation, only a phrase shared quietly, almost cautiously.

Emmy did not react with surprise, but with a form of contained relief.

She understood that in the end he had managed to evade what terrified him most.

A public death subjected to the executioner’s ritual.

Inside her still echoed the words she had heard him say many times.

They won’t hang me.

The real blow came shortly after when she had to explain to Eda that her father would not return.

The girl, unable to fully grasp the loss, imagined that an angel had come down from heaven to deliver the poison.

Emmy did not break the fantasy, but the wound was deep.

Years of unshakable happiness were buried beneath a definitive absence.

Life, she would later write, had lost all meaning for me.

From then on, a slow but relentless decline began.

Emmy was arrested, fell ill, lived in miserable conditions, and even had to be separated from her daughter for long periods.

In the denazification processes, several witnesses recognized her past help, but the verdict was not based on facts, rather on associations.

She was reproached for her marital loyalty.

The only thing they could condemn me for was having loved my husband, she would declare without ambiguity.

She lost almost everything.

Properties, reputation, comfort, nobility, and luxury gave way to an austere life marked by necessity.

But Emmy never renounced her past.

She continued writing letters to Herman as if the bond, though invisible, remained alive.

She found in her daughter, Eda, the only reason to resist.

Over time, she learned to see pain and joy as inseparable parts of the same life.

News

🎰 They Bought A Lion In A Shop….1 Year Later, The Reunion Will MELT You

In 1969, you could buy a lion at Herods. Not a stuffed one, not a photograph, a real living, breathing…

🎰 Unware of His Wife’s Plans, Night After His Wedding He Hid Under The Bed To Prank Her-But Then…

I was flat on my stomach under the king-size bed, holding my breath like a foolish teenager. My suit jacket…

🎰 This 1879 photo seems sweet — until experts discover something disturbing about the enslaved young

This 1879 portrait looked like a reunion until experts found something disturbing about the enslaved girl. Dr. Amanda Chen stared…

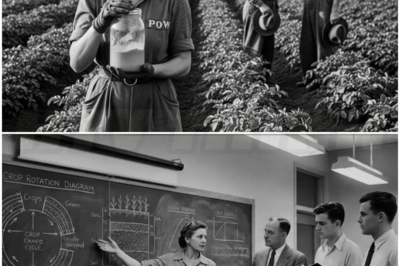

🎰 How One German Woman POW’s ‘GENIUS’ Potato Trick Saved 2 Iowa Farms From Total Crop Failure

May 12th, 1946, Webster County, Iowa. John Patterson stood in his potato field at dawn, staring at rows of withered…

🎰 This is What the Prisoners Did to the Nazi Guards After the Liberation of the Camps!

Spring of 1945 when the Allied armies entered Dhaka, Bookenvald, and Bergen Bellson. The concentration camp system was already disintegrating….

🎰 Black Maid Greeted Korean Mafia Boss’s Dad—Her Busan Dialect Greeting Had Every Guest Frozen..

Black maid greeted Korean mafia boss’s dad. Her Busan dialect greeting had every guest frozen. The entire room went silent….

End of content

No more pages to load