For more than a century, he existed only as a shadow.

A figure slipping through fog-choked streets, vanishing into alleys, leaving mutilated bodies and unanswered questions behind. The world knew him only by a name that became legend: Jack the Ripper. He had no confirmed face, no proven identity—only terror, myth, and endless speculation.

Until now.

After 137 years, modern science has done what Victorian investigators could not. A single piece of fabric, long dismissed and forgotten, has finally spoken. DNA recovered from a silk shawl found at the scene of one of the Ripper’s murders has produced a match—one that points decisively to a man police suspected all along.

His name was Aaron Kosminski.

In 1888, London’s Whitechapel district was a place of desperation and decay. Overcrowded tenements, disease, poverty, and hunger defined daily life. Coal smoke mixed with damp air to create the infamous “pea-soup fog,” so thick it rendered streetlamps useless and swallowed entire streets in darkness.

For a killer, it was perfect cover.

Between August and November of that year, five women—Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly—were brutally murdered. All were poor, vulnerable, and living on the margins of society. All were killed within a few streets of one another.

The murders were savage, intimate, and terrifyingly methodical. Panic swept the city. Newspapers screamed headlines. Letters poured in—some real, many hoaxes—one of them signed for the first time with the name that would echo through history: Jack the Ripper.

A Case That Wouldn’t Die

The Metropolitan Police launched one of the largest investigations of the era. More than 2,000 people were interviewed. Dozens of suspects were questioned. Yet the killer was never caught.

Part of the failure was circumstance. There was no forensic science in 1888—no fingerprints, no blood typing, no DNA. Crime scenes were trampled by crowds. Evidence was mishandled or destroyed. One of the most infamous examples came after the murder of Catherine Eddowes, when police found a chalked message near the scene reading:

“The Jews are the men that will not be blamed for nothing.”

Fearing anti-Semitic riots, the message was erased before it could be photographed or analyzed.

Another haunting clue arrived in the mail: a small box containing half a human kidney, sent to George Lusk of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee. Catherine Eddowes had indeed had a kidney removed during her murder, and doctors confirmed the organ was human and diseased—consistent with Eddowes’ known medical condition. But once again, investigators had no way to prove its origin.

The trail went cold.

Or so the public believed.

A Suspect Hiding in Plain Sight

Behind the scenes, senior officers quietly focused on one man: Aaron Kosminski, a 23-year-old Polish Jewish immigrant who lived and worked in Whitechapel as a hairdresser.

Kosminski had fled Eastern Europe to escape pogroms and settled in London with his family. By contemporary accounts, he suffered from severe mental illness—likely paranoid schizophrenia. He experienced hallucinations, violent outbursts, and harbored what police described as a “great hatred of women.”

Chief Constable Sir Melville Macnaghten named Kosminski as a prime suspect in an internal memorandum. Chief Inspector Donald Swanson, who oversaw the entire Ripper investigation, later wrote in the margins of a memoir that the killer was Kosminski and that he had been confined to an asylum.

Kosminski was committed to Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum in 1891.

The murders stopped.

But without forensic proof or cooperative witnesses—one reportedly refused to testify against a fellow Jew—the police had no case that could stand in court. The truth remained unofficial, buried in files and marginal notes, while legend took over.

The Shawl That Changed Everything

The turning point didn’t come in a courtroom or police archive. It came at an auction house in 2007.

Russell Edwards, an author and amateur detective obsessed with the Ripper case, purchased a stained, tattered silk shawl believed to have been recovered from the scene of Catherine Eddowes’ murder on September 30, 1888. The shawl had been passed down through the family of a police officer who allegedly took it from the scene.

Most experts dismissed it as worthless—a likely fake in a market flooded with Ripper memorabilia.

Edwards saw something else.

DNA.

He brought the shawl to Dr. Jari Louhelainen, a forensic geneticist at Liverpool John Moores University who specializes in extracting genetic material from ancient, degraded samples.

Against all odds, usable mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) was recovered.

Science Meets History

Mitochondrial DNA is inherited exclusively through the maternal line and changes very little over generations. That makes it uniquely valuable for historical cases.

First, researchers tested whether the shawl had truly been at the crime scene. They compared mtDNA from bloodstains on the fabric to a living descendant of Catherine Eddowes’ sister. The match confirmed the shawl’s authenticity.

Then they found something else.

Mixed with Eddowes’ blood were biological traces consistent with semen—the genetic signature of the killer.

The team traced a living maternal descendant of Aaron Kosminski’s sister. When they compared the mtDNA profiles, they matched.

After 137 years, science pointed to the same man Victorian police had suspected all along.

The findings were published in the Journal of Forensic Sciences in 2019 and subjected to peer review. While critics rightly note the limitations of degraded samples and the possibility of contamination, the researchers concluded the evidence strongly supports Kosminski as the source of the DNA.

No historical case can offer modern courtroom certainty—but combined with police records, witness accounts, geographic profiling, psychiatric history, and the timeline of Kosminski’s institutionalization, the conclusion is overwhelming.

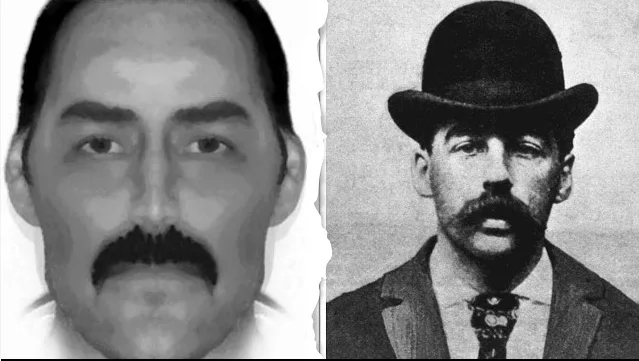

The Ordinary Face of Evil

The revelation is unsettling not because it’s dramatic—but because it isn’t.

Jack the Ripper was not a royal conspirator, a brilliant surgeon, or a criminal mastermind. He was an ordinary man, deeply mentally ill, living among his victims, hidden in plain sight.

The myth endured because the truth was too mundane to satisfy imagination.

Kosminski died in 1919, institutionalized and forgotten, while his alias became immortal.

When the Fog Lifts

Jack the Ripper was never caught by genius deduction or relentless policing. He was stopped because his own illness overtook him. The case went unsolved not for lack of suspicion, but because the world lacked the tools to prove what investigators already knew.

Until now.

The fog that once concealed Whitechapel’s most infamous killer has finally lifted. History has spoken—and it has named him.

But the story leaves us with a chilling question:

How many other truths remain buried, waiting for the right technology to drag them into the light?

And what secrets, even now, are still hiding in the shadows—watching, waiting, patient as time itself?

News

🎰 “No, Man.” Why Dustin Poirier Will Never Squash the Beef With Conor McGregor

“So… would you say the beef has been squashed? All is good?” “No, man.” That was it. No pause. No…

🎰 When Trash Talk Turns Cinematic: How Paramount’s UFC 324 Promo Set the MMA World on Fire

At first, it looked like nothing more than standard fight-week trash talk. Paddy Pimblett was smiling.Justin Gaethje was staring straight…

🎰 UFC’s Dream Match Collapses as Justin Gaethje Derails the Patty Pimblett Hype Train

The first UFC event following the promotion’s official partnership with Paramount Plus is in the books—and almost immediately, the UFC’s…

🎰 Tom Aspinall claps back after ‘catching strays’ from Dana White over eye injury after UFC 324

Tom Aspinall appeared baffled to be the subject of one of Dana White’s infamous rants in the aftermath of UFC…

🎰 Dillon Danis joins Ilia Topuria in mocking Paddy Pimblett after UFC 324 defeat

Dillon Danis finally got one over on Paddy Pimblett last night as he watched his rival lose for the first…

🎰 UFC veteran simultaneously thanks and proves Dana White wrong by sharing post-fight bonus receipts

UFC 324 marked the start of a new system for earning post-fight bonuses inside the Octagon. Dana White hadn’t been…

End of content

No more pages to load