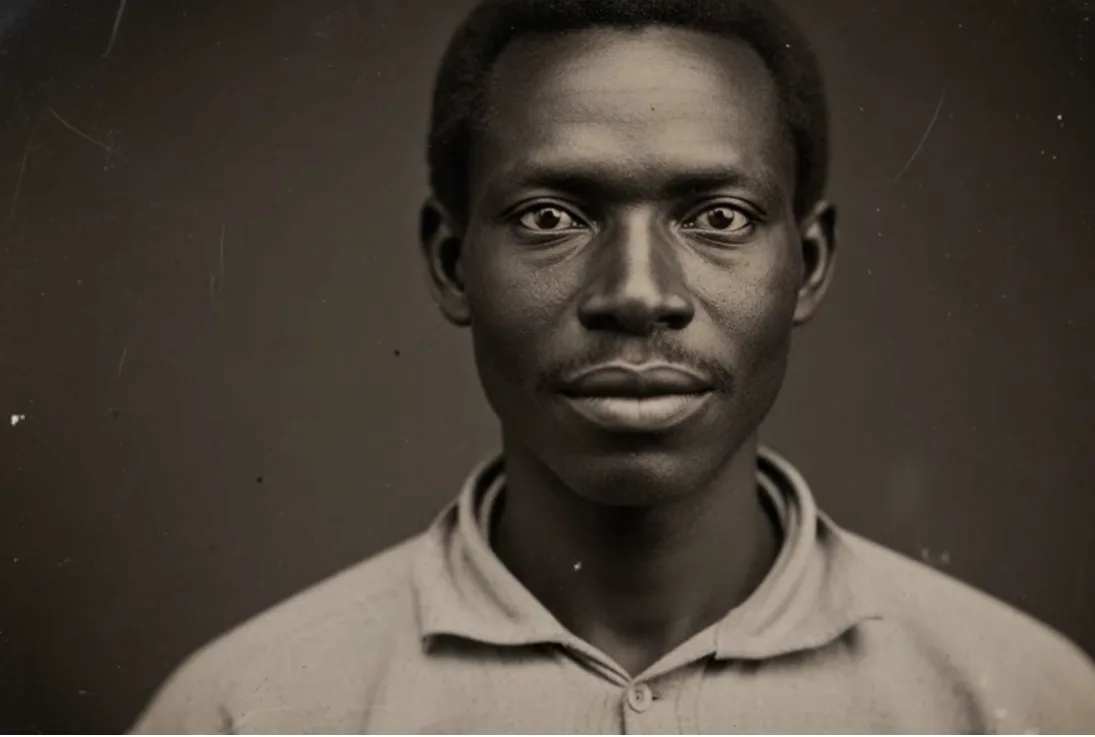

December 7th, 1859. Lot 43. Male, approximately 32 years, origin unknown.

The notation that follows, written in faded ink by an auctioneer named William Marsh, reads:

Highest bid withdrawn. Sale completed under protest. Buyer warned of documented anomalies. Price: $400.

Significantly below market value for a prime-age male.

What made this entry extraordinary wasn’t the low price—though that alone raised questions. It was the seventeen-page attachment stapled behind it: a collection of testimonies from three previous owners, two ship captains, a Methodist minister, and a Texas Ranger. All describing the same impossible phenomenon.

The man they were selling could read and write in seven languages. Perform mathematical calculations that took trained engineers hours, in moments. Recite entire books after hearing them once. Demonstrate knowledge of astronomy, navigation, medicine, and law that rivaled university professors.

In 1859 Texas, such abilities in an enslaved man weren’t just unusual. According to every witness who’d encountered him, they were impossible.

Before we uncover how this man’s intelligence became the most dangerous secret in Galveston, I need you to do something. Hit that subscribe button right now—because stories like this, the ones that challenge everything we thought we knew about American history, are exactly what we uncover here. Drop a comment telling me where you’re watching from. These buried stories deserve to reach every corner of the world.

Now, let’s discover why Galveston’s wealthiest plantation owners called this slave the most terrifying purchase they’d ever witnessed. Not because of his strength or defiance, but because of what existed inside his mind.

William Marsh had conducted slave auctions in Galveston for eleven years. The Strand, the warehouse district along the Gulf waterfront, handled thousands of transactions annually, making Galveston second only to New Orleans in the Texas slave trade. Marsh prided himself on knowing merchandise. But on the morning of December 7th, 1859, he stood in his office holding documents that made his hands shake.

The man scheduled for Lot 43 had arrived three days earlier on a steamship from New Orleans, accompanied by paperwork unlike anything Marsh had seen. The seller, a cotton broker, had included written warnings from every person who’d previously owned or transported this particular slave. The testimonies read like fevered fantasies. Then Marsh met the man himself.

His name in the catalog was listed simply as Solomon.

He stood five-eleven, well-muscled, with hands that showed calluses from fieldwork but also careful maintenance. His face carried no distinguishing scars. What distinguished him was far more subtle and unsettling: his eyes held an awareness that made Marsh deeply uncomfortable.

During the standard assessment, Marsh asked, “Can you read?”

A slight pause. “Yes, sir.”

“How did you learn?”

“I taught myself, sir. By observing letters and words, understanding patterns, practicing when I could.”

Marsh set down his pen. Self-taught literacy among slaves was rare and dangerous. But what followed was incomprehensible.

Solomon explained, in calm, precise English, that he could speak French, Spanish, German, Latin, and some Greek. That he could perform complex calculations mentally. That he remembered everything he saw or heard. “My mind holds information the way a ledger holds numbers,” he said. “I cannot explain why this is true. I only know it has been true for as long as I can remember.”

Marsh spent the next two days reading through the attached testimonies. Each one confirmed Solomon’s claims, with details that made the phenomenon even more inexplicable.

The first testimony came from a Virginia planter who’d purchased Solomon in 1854. He wrote of how Solomon had observed tobacco harvesting for six hours, then worked with an efficiency that exceeded men with twenty years’ experience. How he’d correctly predicted harvest timing based on weather patterns the overseer had dismissed. How, when shown a page from an agricultural journal for thirty seconds, Solomon had recited it back word-for-word, including footnotes. The planter concluded: “I sold him because I was housing someone whose intelligence exceeded my own, who understood systems I could barely grasp, and who remained enslaved only because of the color of his skin.”

The second testimony was from a New Orleans cotton broker who’d owned Solomon for eight weeks. He described how Solomon had corrected a significant accounting error, spoke French better than his wife, and warned about structural weaknesses in a ship’s hull—a warning later proven true when the ship developed leaks. “I sold him because I found myself unconsciously beginning to defer to his judgment,” the broker wrote. “A man cannot function as a merchant when his slave understands commerce better than he does.”

The third testimony came from a ship captain who’d transported Solomon. During a storm, when the navigator struggled with complex celestial calculations, Solomon—sitting in chains—quietly announced their position, correct to within three miles, despite having no instruments or charts. “I’ve sailed for thirty years,” the captain wrote. “Solomon’s abilities exceeded all educated men I’ve known. A man with his intelligence should not exist in chains. And yet there he was, headed to auction like livestock.”

Marsh understood the problem immediately. Solomon would be nearly impossible to sell. Most buyers wanted workers who were strong, obedient, and simple. Intelligence in a slave made owners nervous. Extraordinary intelligence would be terrifying.

His business partner suggested lying, selling Solomon as a standard field hand. Marsh refused. “That’s fraud. And it’s dangerous.” Instead, he prepared the auction listing with full disclosure, attaching all the testimonies. The description ended with an unprecedented warning: “Buyer assumes full responsibility for management of unusual capabilities. No refunds or exchanges.”

The auction began normally on December 7th. But as Lot 43 approached, the atmosphere changed. Buyers had read the testimonies. By the time Solomon stood on the platform, most had moved to the back or left entirely.

“Lot 43,” Marsh announced, his practiced enthusiasm sounding hollow. “Male, approximately thirty-two years, excellent physical condition.” He paused. “As noted in the documentation provided, this lot demonstrates unusual intellectual capabilities. Special terms apply.”

Silence.

Marsh opened the bidding at $600. Nothing. $500. Nothing. One by one, the remaining buyers shook their heads and walked out.

“$400,” Marsh said desperately. “Gentlemen, at this price, you’re buying him at half his physical value alone.”

A hand went up at the back of the room.

“Sold to Mr. James Blackwood of Oleander Plantation for $400.”

James Blackwood was a wealthy planter who owned six thousand acres of cotton land thirty miles inland. He’d built his fortune through systematic efficiency and prided himself on recognizing opportunities others missed. As he signed the purchase documents, he waved away the attached testimonies. “I’ve read them. I understand what I’m buying. This man’s intelligence isn’t a problem. It’s an asset if managed correctly.”

Marsh watched them leave, a deep unease settling in his gut. He wrote in his personal journal that evening: “Blackwood was pleased with his purchase. I cannot shake the feeling he shouldn’t be.”

Oleander Plantation, Texas – December 1859 to March 1860

Blackwood assigned Solomon to the main house work crew initially, wanting him close for observation. For a week, Solomon worked steadily, quietly, observing everything. Then Blackwood decided to test the testimonies.

In his study, he gave Solomon a complex calculation involving cotton yields, market prices, and expenses—a problem that had taken Blackwood thirty minutes with pencil and paper. He read Solomon the variables. Solomon responded immediately: “The projected profit is $4,273.42, sir.”

Blackwood checked his own figure. Exactly.

He tested Solomon with languages, switching to French, then Spanish. Solomon responded fluently, his accent superior to Blackwood’s own. He showed Solomon a page from a medical text for thirty seconds, then took it away. Solomon recited it perfectly, word for word, including technical terminology and footnotes.

Blackwood’s initial excitement curdled into something more complex. Solomon wasn’t just intelligent. He was intellectually superior to Blackwood himself, to anyone Blackwood had ever known.

Over the following weeks, Blackwood found himself increasingly reliant on Solomon’s abilities. He brought him into the study daily, presenting plantation management problems. Solomon solved them instantly: market projections, crop rotation strategies, equipment diagnostics. The plantation’s efficiency improved. But a fundamental crack was widening in the social structure.

The head overseer, Porter, warned Blackwood: “Sir, the other workers are noticing. They see you consulting him, deferring to his judgment. It undermines the structure we depend on. How can we maintain authority when slaves see one of their own operating as your adviser?”

Blackwood dismissed the concern, but Porter’s words lingered. The fundamental structure. Slavery required strict hierarchy, absolute distinction between owner and owned. Solomon’s intelligence threatened that distinction, made the categories seem arbitrary.

By February, Blackwood was not just consulting Solomon but seeking his company for conversations about philosophy, science, history. These discussions left Blackwood exhilarated and deeply unsettled. He was engaging as an intellectual equal with a man he legally owned as property.

The contradiction became unbearable.

In early March, Blackwood confronted Solomon directly. “I need to ask you something honestly,” he said, his voice strained. “I own you. Legally, completely. Yet you are intellectually superior to me in ways I can’t measure. How am I supposed to reconcile that? How am I supposed to maintain authority when I know you are more capable than I am?”

Solomon replied with careful precision. “Sir, the contradiction you’re experiencing isn’t caused by me. It existed before you purchased me. The system requires believing that enslaved people are inferior, naturally suited to servitude. That belief can only be maintained if evidence contradicting it is suppressed. My existence makes the evidence impossible to ignore. I don’t create the contradiction. I simply make it visible.”

The truth of those words settled like a weight. Blackwood could no longer pretend.

The crisis point came on March 15th, when an abolitionist pamphlet was found in Solomon’s possession. Blackwood, already wrestling with his conscience, exploded—not at Solomon, but at himself, because every argument in the pamphlet echoed his own recent thoughts.

“Do you believe slavery should be abolished?” Blackwood demanded.

“Sir, I believe slavery is morally indefensible,” Solomon said, his gaze unwavering. “I believe it corrupts everyone it touches. And I believe you’ve reached the same conclusions, which is why my presence troubles you so deeply.”

Blackwood dismissed him, then sat at his window until long after dark, watching the slave quarters. Solomon hadn’t told him anything revolutionary. He’d simply made visible what had always been true.

On March 28th, 1860, James Blackwood did the unthinkable. He called his lawyer and had manumission papers drawn up. He handed them to Solomon along with fifty dollars. “You’re free,” Blackwood said. “Under state law, you have ninety days to leave Texas.”

Solomon studied the papers. “Why free me when you could have sold me for profit?”

“Because you were right,” Blackwood said, his voice rough. “About everything. I can’t own someone who’s forced me to see truths I’d spent my life avoiding.”

“And the others?” Solomon asked quietly. “The one hundred and forty-three people who remain enslaved here. What about their right to freedom?”

Blackwood had no answer. He was freeing one man while keeping over a hundred others in bondage. The contradiction was obvious and damning.

Solomon nodded, accepting the honesty if not the justification. “Then I thank you for my freedom, Mr. Blackwood, while acknowledging its incompleteness.”

He walked out of the study, off the plantation, and onto the road toward Galveston.

The Aftermath – 1860 and Beyond

Solomon’s departure triggered a chain reaction. Word spread through Oleander that a man had been freed because his intelligence made slavery’s injustice undeniable. The enslaved workers began asking questions. Small acts of resistance multiplied. The plantation’s efficiency crumbled.

Meanwhile, Blackwood faced vicious ostracism from the planter community. He was isolated, his business relationships dissolved. In June, desperate to reconcile his conscience, he announced a plan for the gradual emancipation of all Oleander’s enslaved people over five years.

The response was immediate and brutal. He was completely cut off. By December 1860, exactly one year after purchasing Solomon, Blackwood lost Oleander Plantation to bankruptcy. It was sold to neighbors who rescinded the emancipation plan. The workers were re-enslaved.

Blackwood moved to Galveston, living in modest circumstances, working as a clerk. He never recovered his wealth or status, but his later writings suggest he never regretted his attempt. “I purchased Solomon believing I was acquiring a valuable asset,” he wrote in 1862. “Instead, I acquired a mirror that reflected truths I’d spent my life avoiding… I lost everything making those gestures. I would lose it all again rather than live with the alternative.”

Solomon’s Journey

Solomon traveled north, using his intelligence to navigate toward free states. In Memphis, his abilities caught the attention of a shipping merchant, who hired him as a logistics consultant—a role he performed brilliantly, though his contributions had to be kept discreet, attributed to white employees.

By mid-1861, as the Civil War began, Solomon’s analytical skills attracted Union officers in Cincinnati. He worked unofficially on complex military logistics: calculating supply routes, projecting resource needs, analyzing enemy movements. His work was invaluable, yet he received no official recognition. An officer confided in his diary: “We depend on this man’s intelligence while denying his humanity sufficiently to credit his contributions. We use him as we would a calculating machine—valuable for output, but unworthy of recognition.”

Solomon also assisted Underground Railroad networks, his perfect memory ideal for coordinating escape routes without written records. A Quaker abolitionist wrote of him: “He operates in shadows, essential but invisible, brilliant but constrained by racial prejudices that deny his fundamental humanity.”

After the war, Solomon lived in Cincinnati, working as a consultant and analyst. He wrote extensively about his experiences, his reflections preserved in letters and journals discovered centuries later. In one powerful passage, he wrote:

“Intelligence in bondage becomes a curse rather than a blessing. It means understanding fully the injustice of your position… Now in freedom, intelligence proves equally problematic. I understand too well how precarious this freedom is… My unusual memory means I forget nothing. Every moment of slavery remains perfectly preserved. Freedom cannot erase slavery’s impact when the past remains eternally present.”

In 1868, Blackwood wrote to Solomon from Galveston, expressing guilt and seeking closure. Solomon’s reply was profound:

“You express guilt about freeing one man while keeping others enslaved… What you attempted was imperfect, compromised, limited by your capacity to sacrifice everything for principle. But it was also genuine, costly, and significant… You freed me because my intelligence made slavery’s injustice unavoidable. But what about those whose intelligence was less obvious? Were they less deserving of freedom? The answer is no. Yet you could not extend to them the recognition you extended to me. This limitation wasn’t your personal failing. It was systemic. What slavery’s end must ultimately accomplish is not just freeing exceptional individuals like myself, but recognizing that exceptionalism should never have been required for freedom in the first place.”

Solomon died in Cincinnati in 1896. His brief obituary read: “Solomon Freeman, Negro resident, employed in various business capacities.” It mentioned none of his extraordinary life.

The Ledger’s Truth

The auction ledger entry remains. Lot 43. $400. A price paid not for a man’s labor, but for the terrifying truth he carried.

Solomon’s story is not just about one man’s phenomenal mind. It’s about what that mind revealed: that slavery’s justifications were fragile fictions, maintained by suppressing evidence of Black intelligence and humanity. Solomon was a living contradiction to the myth of natural inferiority—so threatening that he was sold at a loss, and later freed not from benevolence, but because his owner could no longer bear the cognitive dissonance.

His life asks us a haunting question: Why did a man have to be exceptional to be seen as human? Why wasn’t ordinary humanity enough?

The ledger, the testimonies, the letters—they all survive. They tell a story American history tried to bury: that genius wore chains, that truth was sold under protest, and that sometimes, the most dangerous thing a person can be is impossible to ignore.

If this story challenged you, share it. Subscribe for more buried histories. And tell me in the comments: what does it mean that Solomon had to be extraordinary to be seen as deserving of freedom? I read every one.

Until next time, keep questioning the official stories. The truth is often hidden in the footnotes.

News

Antique Shop Sold a “Life-Size Doll” for $2 Million — Buyer’s Appraisal Uncovered the Horror

March 2020. A wealthy collector pays $2 million for what he believes is a rare Victorian doll. Lifesize, perfectly preserved,…

Her Cabin Had No Firewood — Until Neighbors Found Her Underground Shed Keeping Logs Dry All Winter

Clara Novak was 21 years old when her stepfather Joseph told her she had 3 weeks to disappear. It was…

My Wife Went To The Bank Every Tuesday for 20 Years…. When I Followed Her and Found Out Why, I Froze

Eduardo Patterson was 48 years old and until 3 months ago, he thought he knew everything about his wife of…

Her Father Lockd Her in a Basement for 24 Years — Until a Neighbor’s Renovation Exposed the Truth

Detroit, 1987. An 18-year-old high school senior with a promising future, vanished without a trace. Her father, a respected man…

“Choose Any Daughter You Want,” the Greedy Father Said — He Took the Obese Girl’s Hand and…

“Choose any daughter you want,” the greedy father said. He took the obese girl’s hand. Martha Dunn stood in the…

Her Son Was Falsely Accused While His Accuser Got $1.5 Million

He was a 17-year-old basketball prodigy. College scouts line the gym. NBA dreams within reach. But one girl’s lie shattered…

End of content

No more pages to load