Imagine waking up to the sound of shouting that doesn’t rise but stops. Cut short by shock. On March 3rd, 1931, just after sunrise, a rope creaked in the cold air above West 131st Street, Harlem. No speeches, no warning shots, just a body left where everyone would see it. A nephew of Lucky Luciano. Italian blood hung in black Harlem. The message wasn’t subtle. It was theatrical and it was meant to humiliate.

A coffee cup cooled untouched on a diner counter across the street. A folded newspaper slipped from a man’s hand and stayed on the sidewalk. 200 people gathered, then froze, unsure whether to look up or look away. Someone whispered the letters K like a prayer said backward. By 8:17 a.m. three patrol officers arrived. By 8:19, they were already backing up, hands loose at their sides, eyes scanning the windows instead of the rope.

This wasn’t just murder. It was a public insult performed in daylight. An announcement that the rules no longer mattered. and everyone understood the dangerous question it posed. What happens when humiliation is intentional and witnessed.

Lucky Luciano was not there. That absence mattered.

By noon, word reached him through a man who spoke too softly and wrote nothing down. Lucky listened. He didn’t interrupt. He didn’t ask questions. He stared at a stain on the table shaped like a continent and said only one thing. Give me a week.

By nightfall, Harlem looked normal to anyone passing through. Street lights came on. Storefronts glowed. A man played a muted trumpet somewhere above Lennox Avenue. But inside the neighborhood, something had shifted subtle and irreversible.

The rope was gone by 4:40 p.m., cut down clean. No ceremony, no photographs taken by police. Officially, the report would later say unknown assailants, unknown motive. Unofficially, everyone knew who had done it. The Ku Klux Klan hadn’t just killed a man, they had staged him. Italian blood in Black Harlem wasn’t random. It was a deliberate fracture attempt.

What followed wasn’t outrage. It was discipline. A barber on West 135th Street, swept hair from his floor, twice slower than usual, eyes fixed on the door. A woman folded the same newspaper three times at her kitchen table, never opening it. In a numbers house near 7th Avenue, a runner stopped mid-step, turned around, and refunded every bet without explanation. Money, like words, suddenly felt dangerous.

Police radios crackled all evening. According to department logs, patrol coverage in Harlem that night increased by 18%. Yet arrests dropped to zero, not one. Officers drove through intersections without slowing. A few killed their engines and sat quietly watching stoops where no one sat anymore. Harlem had learned long ago that survival sometimes meant absence.

And still no retaliation. That was the first twist. Everyone expected violence. A body answered with another body. That’s how the city usually worked. But instead, there was nothing. No Italian crews storming up town, no guns, no meetings overheard, just silence stretched thin enough to hurt.

Lucky Luciano spent that night, not in Harlem, but downtown in a borrowed apartment near Mulberry Street. The curtain stayed half drawn, a single lamp burned. On the table, a cup of coffee he never touched, and a small notebook confiscated months earlier from a dock worker. Its pages blank now, except for numbers written so faintly they looked erased.

Three men spoke to Lucky that night. Each offered a solution. Each promised speed. Each ended with the same word tonight. Lucky said no to all of them. He asked instead about the rope, where it was bought, who sold it, what kind of knot had been used. One man said it was a hangman’s knot tied clean professional. Lucky nodded once. That told him enough. This wasn’t spontaneous hate. It was organized theater.

Outside a car idled too long at the curb. Lucky noticed. He watched its exhaust drift upward and dissipate. When it finally pulled away, he said something almost too quiet to hear. They want a reaction, so we won’t give them one.

By midnight, rumors began to spread, not of revenge, but of a deadline. 7 days. No one could say where the number came from. No note, no threat, just a shared understanding moving mouth to ear, bar to bar, church to backroom. 7 days to correct a humiliation that had been allowed to happen.

The second twist was more unsettling than violence. The city began to adjust around that expectation. Milk deliveries skipped certain streets. A freight elevator near the Harlem River Yards broke down and stayed broken. A police captain reassigned himself to desk duty without filing the paperwork. Harlem wasn’t preparing for war. It was preparing for consequence.

And the most frightening part for those who understood power was that Lucky Luciano still hadn’t raised his voice.

On March 4th, 1931, Lucky Luciano finally crossed into Harlem. Not loudly, not with protection anyone could see. He arrived just after noon when the streets were busiest and least suspicious. A gray overcoat, no hat. He walked the last half block alone.

The room was above a fish market on East 125th Street. You could still smell salt in the floorboards. Four men waited inside. None spoke when Lucky entered. That silence mattered more than respect. It meant they already understood this wasn’t a meeting. It was a listening session.

Lucky sat. He placed his gloves beside a folded street map. A coffee cup was poured for him automatically. He didn’t touch it. One of the men began listing names. Klan sympathizers. Night riders rumored to come up from Yonkers. A warehouse contact near the Harlem River Drive. Lucky raised one finger. The man stopped mid-sentence. That finger, steady, almost gentle, was the first visible assertion of control since the hanging.

Lucky asked one question. Who saw it? Not who did it? Not how. Who saw it? They answered carefully. Children on stoops. Women at windows. 200 maybe more. That number stuck. Lucky repeated it once like he was testing its weight. 200 witnesses meant 200 memories, 200 private verdicts. You couldn’t erase that with blood.

This was the third twist. Lucky wasn’t planning revenge. He was auditing shame.

He asked about police timing. 8 minutes from first call to arrival. Too fast. Someone had been waiting. That meant cooperation or fear. In 1931, the NYPD employed just over 15,000 officers citywide, but only a fraction worked Harlem beats. Everyone in the room understood what that implied. Patrols were thin reputations thinner.

Lucky finally touched the notebook. He didn’t open it, just rested his palm on the cover. They wanted us loud, he said. They wanted panic. Instead, we’ll give them precision.

Outside, a fish vendor shouted prices that didn’t change. Inside, Lucky began assigning days, not tasks. Days. Tuesday would be for observation. Wednesday for confirmation. Thursday for pressure. Each step depended on cooperation, not force.

One man asked the obvious question voice tight. What if they move again? Lucky looked at him. A long look, not angry, measuring. They won’t, he said. They already had their show.

That afternoon, something unusual happened across Harlem. People began to talk, not to police, not to reporters, but to each other. Quiet confirmations, small corrections. A man at a bar said the rope had been bought on Amsterdam Avenue, not downtown. Another said the truck seen idling belonged to a laundry company that hadn’t washed clothes in weeks. A woman mentioned a patrolman who’d crossed the street before the body was even spotted. None of this went on paper.

By evening, Lucky visited one place, only a small church on West 132nd Street. No announcement, no prayer. He stood in the back as a janitor swept the aisle. A single light flickered. Lucky watched the broom push dust into neat lines, then scatter them again. He left a donation exactly $7 on the table by the door. That number would matter later.

The fourth twist came quietly, almost invisibly. While everyone expected Lucky Luciano to harden, to become colder, he did the opposite. He slowed down. He allowed Harlem to feel involved, not as soldiers, but as witnesses who mattered.

That night, police reports noted an anomaly emergency calls from Harlem dropped by 27% compared to the previous week. Less noise, less chaos, more control.

Back in the fish market room, one man finally broke protocol and asked what everyone else was afraid to. What happens on the seventh day? Lucky put his gloves back on. He stood for the first time since the rope. He smiled, not with humor, but with certainty. By then, he said they’ll understand who decides what gets remembered.

No one followed him out. They didn’t need to.

By March 5th, 1931, the countdown had a shape. Not written, not spoken aloud. But everyone felt it tightening like a watch ticking inside a pocket you couldn’t reach. Day three was for pressure.

Lucky never issued orders the way men expected. There were no threats, no raised voices, no promises of blood. Instead, things began to fail small at first, then in patterns too deliberate to ignore. A printing press on West 138th Street jammed and stayed jammed. The owner swore the rollers had been tampered with, but nothing was broken, just misaligned enough to stop work. A delivery truck carrying coal to three buildings with known Klan sympathizers took a wrong turn and ended up stalled near the Harlem River driver gone keys still in the ignition. No theft report filed. No witness statements given.

This was the next twist. Retaliation wasn’t aimed at men. It was aimed at function.

Lucky spent most of the day walking. No car, no escort. He moved through Harlem like a man counting steps. He stopped once at a lunch counter near Lennox Avenue, sat down, ordered coffee, and left before it arrived. The waitress noticed. She would mention it later years later when people asked how they knew something serious was coming. He didn’t drink, she said. That’s how I knew.

Behind the scenes, information moved faster than fear. A dock clerk quietly altered a ledger. A janitor left a door unlocked for exactly 12 minutes. A church secretary misfiled a donation receipt tied to an out-of-state group no one wanted their name next to. None of these people had met Lucky. That was the point.

The New York City Police Department noticed the pattern but couldn’t touch it. On paper, nothing illegal was happening. No bodies, no guns, no riots. Yet by Wednesday night, internal memos flagged unusual non-compliance across Harlem precincts. Officers reported doors not being answered. Questions met with silence. Informants suddenly forgetting names they’d used for years.

Lucky met that evening with one man only in a narrow apartment overlooking St. Nicholas Park. The curtains were open. They wanted to be seen. On the table between them lay a folded newspaper headline, unread deliberately up-turned. The man asked if it was time to escalate. Lucky shook his head. Not yet, he said. They still think this is about anger.

The deadline 7 days was now circulating beyond Harlem. Downtown bars picked it up first, then the docks, then precinct houses. No one could trace it to Lucky, which made it more dangerous. Rumors don’t need leadership. They need repetition.

By the end of day three, the effects were measurable. Freight delays tied to just four addresses caused an estimated $42,000 in losses, a small number citywide, but concentrated enough to send a message. Phone records later showed outgoing calls from those addresses spiked by 61%, most of them unanswered.

That night, Lucky stood alone at a window looking north. He rested his hand on the glass, feeling the vibration of traffic below. For the first time since the rope, his jaw tightened, not in rage, but in recognition. They were beginning to understand, and there were still three days left.

March 7th, 1931. Day five. This was the day fear changed hands. Up until now, the pressure had been abstract. missed deliveries, broken routines, unanswered phones. But on Friday morning, the consequences acquired weight shape. Names whispered carefully only once.

At 9:12 a.m., a payroll envelope meant for a construction crew tied to a known Klan organizer never arrived. Not stolen, not intercepted, simply never delivered. The courier later swore he had made the drop described the doorway perfectly, even remembered the smell of fresh paint in the hall. The envelope itself vanished from memory like a sentence cut mid-thought.

This was the twist no one expected. Money, clean money was being made unreliable.

By noon, four small businesses connected by church donations and shared suppliers reported identical problems. Invoices, unfiled, permits, delayed signatures, questioned. None of it could be traced to Lucky Luciano. None of it could be fixed quickly. And that was the point. Violence ends arguments. Uncertainty extends them.

Lucky spent that afternoon sitting quietly in the back of a barber shop on West 134th Street. No haircut, no conversation. He watched a man trim another man’s hair, slow and careful, as if time itself had become fragile. A folded towel slipped from the chair, and wasn’t picked up right away. No one rushed anymore.

A runner brought Lucky a message written on scrap paper, pencil, barely visible. He read it once and tore it in half. The message wasn’t a threat. It was a request. Can we talk? Lucky didn’t answer. He didn’t need to. Talking was what men asked for when they had lost leverage.

By evening, police commanders faced a decision they wouldn’t write down. Patrols could be increased, but to do what? There were no crimes to stop. Only systems refusing to cooperate, arrests without witnesses, questions without answers. Harlem had become administratively invisible. Statistics later buried in internal summaries showed something unprecedented. Response times improved by 11% yet effective enforcement dropped sharply. Officers arrived faster and left sooner.

Lucky walked past a church just before sunset. A light burned inside. Someone had left a coffee cup on the steps untouched, already cooling. He paused just long enough to notice it, then kept walking.

This is where the story turns outward toward you. If you were a shop owner watching your permit stall, if you were a police captain realizing your authority only worked when people believed in it. If you were part of a group that thought public humiliation was power, what would you do with two days left?

That night, a single sentence began circulating, spoken differently in every mouth, but identical in meaning. Sunday decides everything.

Lucky returned to his room. He sat on the edge of the bed and finally removed his gloves. His hands were steady, not clean, but steady. He looked at the clock. Two days remained.

March 9th, 1931. Day seven arrived without drama. No sirens, no crowds, just a gray morning that felt unfinished. This was the final twist and the most dangerous one. Nothing happened at first.

By sunrise, men who expected retaliation were already awake, staring at ceilings, listening for sounds that didn’t come. By 8:00 a.m., phones rang and stopped ringing. By 10, a downtown insurance office quietly suspended coverage on three properties in Harlem, citing unverifiable risk exposure. No explanation beyond that phrase, no appeal process.

Lucky did not move that morning. He stayed seated at a small table, sunlight cutting across the wood in sharp angles. A confiscated notebook lay open now. Not names, not plans, just times written down the margin. Times that had already passed.

At 11:26 a.m., a warehouse lease tied indirectly to Klan fundraising was flagged for review. At 11:41, a utility crew failed to show up to reconnect power after a routine outage. By noon, two patrol supervisors requested reassignment voluntarily. Later analysis would show that in a single day, administrative friction caused delays across nine separate city departments, a statistical anomaly that wouldn’t be repeated again that year.

This was the moment police leadership understood the trap. To intervene now would require admitting cooperation had failed earlier. To act forcefully would mean acting alone. No witnesses, no cooperation. No paperwork that would survive scrutiny. Authority stripped of belief becomes performance. And performance without an audience collapses.

Lucky finally stood in the early afternoon. He put on his coat. He did not look at the clock again. He walked one block, then another. People noticed him and looked away, not out of fear, but out of respect for the boundary he’d drawn. A man nodded once. Lucky nodded back. That was the entire exchange.

Somewhere, a decision was being weighed by men who had once believed humiliation was permanent. That belief had cost them seven days of control. Seven days of uncertainty. Seven days where nothing worked the way it was supposed to.

Here is the second question, one that matters more than the first. When power stops answering you, do you push harder or do you step back before history notices?

No one knows exactly who made the call. Only that by nightfall, enforcement slowed, files stopped moving, patrol cars stayed parked. The city chose the path that kept it breathing.

Lucky returned to his room as dusk settled. He sat. He closed the notebook. He placed it in a drawer and did not lock it.

Outside, Harlem exhaled, not loudly, not in celebration. Just a long release of tension. No one spoke about what had almost happened. Silence did the work instead.

March 10th, 1931. The eighth day felt different. Not because something new happened, but because nothing else ever would. The street where the rope had hung was clean now. Too clean. Rain had washed the last discoloration from the pavement sometime before dawn. A shopkeeper opened his gate an hour late, then apologized to no one in particular. A folded newspaper sat on a stoop, headline hidden, as if the paper itself understood that words were no longer needed.

The nephew’s body was gone, officially transferred, officially processed, unofficially erased. In New York that year, fewer than 62% of lynching related deaths, North and South combined, ever resulted in indictments. This one would not be among them. No suspects, no follow-ups. The case would be filed under a category officers used when they wanted memory to do the work paperwork refused to do.

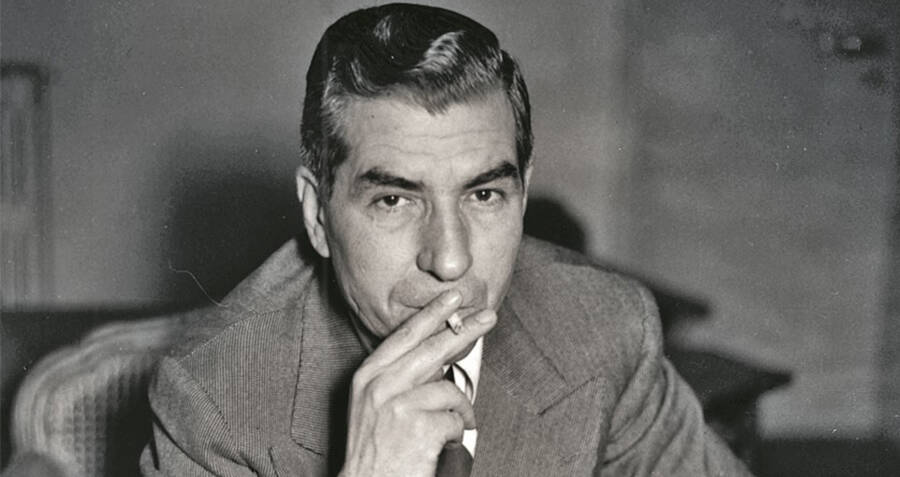

Lucky Luciano did not return to the street. That mattered most of all. Powerful men are remembered for what they do. Enduring men are remembered for what they refuse to repeat.

Lucky never spoke publicly about the hanging. He never demanded tribute. He never even claimed authorship of the seven days that followed. Ownership would have weakened the rule. Instead, something quieter settled in. In Harlem, the lesson traveled faster than any threat. Humiliation when witnessed changes the equation. You could kill a man, but if you staged him, if you turned death into theater, the response would no longer be personal. It would be structural, slow, exhausting, unavoidable.

Police behavior shifted subtly after that week. Patrol routes stabilized. Informants became cautious about exaggeration. Community silence was treated for the first time as a form of intelligence rather than obstruction. An unwritten understanding took hold. Certain lines once crossed in public could not be uncrossed without consequence.

Lucky left New York not long after, not in flight, in completion. Years later, men who had never met him would still repeat the rule without knowing where it came from. Don’t make it public. Don’t humiliate. Don’t confuse dominance with spectacle because if you do, someone else will decide the timeline and history will cooperate with them.

The rope was gone. The street was ordinary again. But the city remembered, not loudly, not proudly, just accurately. History rarely announces when it is finished teaching a lesson. It simply changes behavior and waits to see who notices.

What happened in Harlem that week was not remembered because of blood. It was remembered because restraint forced everyone else to move. The community learned that silence could be coordinated without being commanded. The police learned that authority collapses when belief disappears. And Lucky Luciano learned perhaps more clearly than ever that power lasts longer when it does not rush to be seen.

Public humiliation had been the spark. Not the death alone, but the display of it. The rope in daylight. The witnesses who couldn’t unsee what had been done. From that moment on, nothing was impulsive. Every hour that followed was measured. Every response delayed just long enough to become inevitable.

People often ask why violence didn’t explode. They misunderstand the moment. Violence would have ended the story too quickly. What followed instead was heavier, slower, a lesson that required cooperation from people who would never appear in a report or a courtroom, only in memory.

Years later, the details blurred, the exact street, the exact faces. But the rule remained intact, passed down in quiet warnings and half-finished sentences. Don’t make it public. Don’t confuse humiliation with power. Because once a community witnesses disrespect, the response no longer belongs to any one man. It belongs to time.

Somewhere in Harlem, life resumed the way it always does. Coffee cups were lifted again. Newspapers were unfolded. Patrol cars rolled on their routes. And yet beneath the ordinary motion, the city carried a new understanding, one written not in ink, but in hesitation.

That is how history survives. Not in headlines, not in monuments, but in the choices people quietly stop making.

News

🎰 Raskin Alleges Systematic Epstein Cover-Up in Explosive Hearing, Presents Thousands of Pages of FBI Records

A House Oversight Committee hearing took a dramatic and unexpected turn when Representative Jamie Raskin publicly alleged the existence of…

🎰 The Quiet Phase of Political Collapse: How Resistance to Trump Is Taking Shape Inside Washington

Political collapse is often imagined as something sudden and spectacular—resignations, mass protests, dramatic votes, or explosive scandals. In reality, it…

🎰 A Senate Hearing Erupts as Swalwell Confronts Patel Over Epstein Files and Trump References

No one in Washington expected it to be said so plainly. Not in that room, not on camera, and certainly…

🎰 Saudi Prince Reads Bible To Family To Make Fun of GOD But He Turns Christian Instead

Pay attention to the Saudi prince in white robes reading mockingly. His name is Abid. He just gathered his family…

🎰 The Miracle in Denver — The Adopted Boy Who Spoke with the Virgin Mary in the Garden

“Hi, Mary. I love you.” Ethan Miller was 3 years old when he started talking to someone in the garden…

🎰 Woman Adopted 5 Girls 27 Years ago, But What They Did Years Later Left Her In Shock!

The Woman Who Became a Mother to Five Taking care of five children at once is overwhelming for anyone—no matter…

End of content

No more pages to load