“Man, you come right out of a comic book.”

What many people don’t like about Enter the Dragon is exactly what made it legendary: not everyone got the chance to fully do their thing.

How many times have you watched Enter the Dragon? Five times? Ten times? Enough to memorize every kick Bruce Lee throws?

Because Enter the Dragon isn’t just a movie.

It’s a global cultural landmark.

Released in 1973, the film didn’t just redefine action cinema—it changed who was allowed to stand at the center of the screen. It brought Asian martial arts into Hollywood’s bloodstream, shattered long-standing racial hierarchies, and placed Asian, Black, and White heroes on equal footing for the first time in mainstream cinema.

But even the most devoted fans only know half the story.

Behind this masterpiece are truths the cast stayed silent about for more than fifty years. Stories of racial prejudice, quiet rage, humiliation, sacrifice—and survival. An Asian actor forced to fight Hollywood itself. A Black martial artist battling constant erasure. Women pressured to give up their dignity just to exist on screen.

This is the story no one talked about.

Until now.

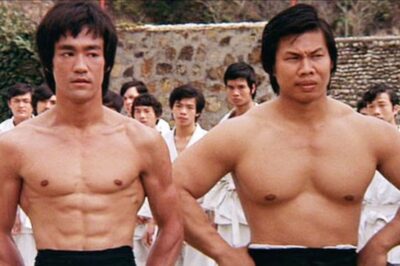

Bruce Lee: Fighting for an Entire Race

Before Enter the Dragon, Bruce Lee had already been pushed out of Hollywood.

In the late 1960s, he pitched a television series about a Shaolin monk wandering the American West. Hollywood took the idea, renamed it Kung Fu, and gave the lead role to a white actor.

Bruce left America in silence.

Back in Hong Kong, he refused to disappear. With Golden Harvest, he unleashed The Big Boss, Fist of Fury, and Way of the Dragon. Asia exploded. Box offices collapsed under demand. Bruce Lee became the most electrifying figure in the region.

Hollywood noticed—too late.

Warner Bros. didn’t return out of respect. They returned because Hong Kong was cheap, and Bruce was unavoidable.

Bruce accepted—but on his terms.

He demanded full creative control, authentic martial arts philosophy, real fight choreography, and respect for Asian culture. Conditions Hollywood had never granted an Asian actor before.

Bruce knew this was his one shot. One failure, and the door would slam shut for everyone who looked like him.

“If I succeed,” he told Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, “Asians will have a chance.”

The pressure nearly destroyed him.

Insomnia. Convulsions. Migraines so intense the world went black. On May 10, 1973, Bruce collapsed in an editing room—diagnosed with acute cerebral edema. Doctors warned him to stop.

He refused.

“If I stop,” he said, “everything disappears.”

On July 20, 1973, Bruce Lee collapsed again. This time, he never got back up. He was 32 years old.

Enter the Dragon would become his final message to the world.

Jim Kelly: Black Power in Motion

Jim Kelly almost wasn’t in the film at all.

Just 48 hours before filming began, the original actor dropped out. Warner Bros. scrambled. A multicultural film without a Black fighter would collapse its entire meaning.

Someone mentioned a Black martial artist in Crenshaw.

Producer Fred Weintraub walked into Jim Kelly’s dojo and froze.

“My God,” he said. “You look like you came straight out of a comic book.”

Kelly wasn’t an actor. He was a fighter. And he carried himself like one.

In Hong Kong, Kelly quickly realized the truth: he was the only Black man on set. And that usually meant being underestimated.

He answered every doubt with action.

Bruce Lee saw him immediately. They trained together. Bruce called him “Brother Jim.”

Williams was originally written as a minor role—fly in, fight, die.

That changed fast.

Director Robert Clouse expanded Kelly’s screen time. Added dialogue. Added presence. What appeared on screen was something audiences had never seen before: a Black hero who wasn’t a servant, villain, or sidekick—but an equal.

The world responded.

But Hollywood didn’t.

Kelly was paid scale. No profit participation. No residuals. While Warner Bros. counted millions, Kelly counted bills.

After Bruce’s death, the studio leaned on Kelly to promote the film—but refused to let him step out of Bruce’s shadow.

They called him “the Black Bruce Lee.”

Kelly rejected it.

“I don’t want to be the Black Bruce Lee,” he said. “I want to be Jim Kelly.”

John Saxon: Learning to Step Aside

John Saxon arrived in Hong Kong as a Hollywood leading man—and immediately realized he wasn’t the center anymore.

Bruce Lee and Jim Kelly dominated the room.

Saxon trained relentlessly, not to outshine them, but to survive beside them. Bruce corrected him constantly.

“Don’t act karate,” Bruce said. “Fight right.”

Saxon pushed for depth in his character, knowing that without substance, he’d disappear. He also fought to protect Kelly’s screen time when the studio tried to reduce it.

For the first time in his career, Saxon understood what it felt like not to be chosen.

And that humility gave his character weight.

A Set Without Mercy

There were no safety nets on Enter the Dragon.

No padding. No breakaway glass. No fake hits.

Bruce Lee received 12 stitches during a fight scene and kept filming. The cobra used on set may not have been venom-free. Some extras were real triad members.

This wasn’t acting realism—it was survival.

Among the nameless stunt performers were Jackie Chan, Sammo Hung, Yuen Biao, and Yuen Wah—young men who bled in silence and later became legends.

Bruce believed fear was necessary.

“If a scene doesn’t scare you,” he said, “the audience won’t feel it.”

The Women No One Remembered

For the women on Enter the Dragon, survival meant something else entirely.

Many Hong Kong actresses refused certain roles due to stigma. The production filled those scenes with sex workers—women who knew they’d be judged but had no other path to the screen.

Some were pressured to go beyond the script. Those who refused were replaced instantly.

Their faces built the world. Their sacrifices were erased from history.

A Legendary Film, Unequal Endings

Enter the Dragon earned over $400 million worldwide—more than 400 times its budget.

Bruce Lee never saw it.

Jim Kelly became an icon but was denied the career he deserved.

John Saxon was overshadowed.

The stunt performers waited decades for recognition.

And the women faded into silence.

Yet the film’s message survived everything:

Heroes are not defined by skin color.

Talent is not owned by one culture.

Prejudice only lasts until someone shatters it.

More than fifty years later, Enter the Dragon still breaks barriers—because the people behind it paid the price in full.

News

🎰 The Tragic Fade of Nate Diaz: From Stockton’s Street-Bred Warrior to a Legend in Limbo

For years, Nate Diaz embodied everything raw, rebellious, and real about mixed martial arts. He was the antithesis of corporate…

🎰 5 Hollywood Stars Dolph Lundgren Refuses to Work With Again — And the Shocking Stories Behind Each Feud

Dolph Lundgren became a global icon the moment he stepped onto the screen as Ivan Drago in Rocky IV—ice-cold, intimidating,…

🎰 Bruce Lee, Bolo Yeung, and the Truth Behind the Silence

For decades, Bruce Lee’s death has been surrounded by noise. Rumors. Theories. Sensational headlines designed to shock rather than explain….

🎰 Ravishing Rick Rude: The Perfect Heel, the Broken Body, and the Death Wrestling Still Won’t Explain

“Was he intense in the ring?” “Oh yeah. He was wound tight.” “Dangerous?” “Very.” That single word—dangerous—follows Rick Rude through…

🎰 Larry Holmes’ Pennsylvania Country Life — From Heavyweight Glory to a Quiet Legacy

Fame once followed Larry Holmes everywhere.Roaring arenas. Flashing lights. The weight of a heavyweight crown. Today, his story unfolds far…

🎰 How Riddick Bowe Lives Today: From $80 Million to Brain Damaged and Broke

Riddick Bowe was the undisputed heavyweight champion of the world.He beat Evander Holyfield in 1992.He made over $80 million in…

End of content

No more pages to load