For nearly a decade, the interview was thought to be lost.

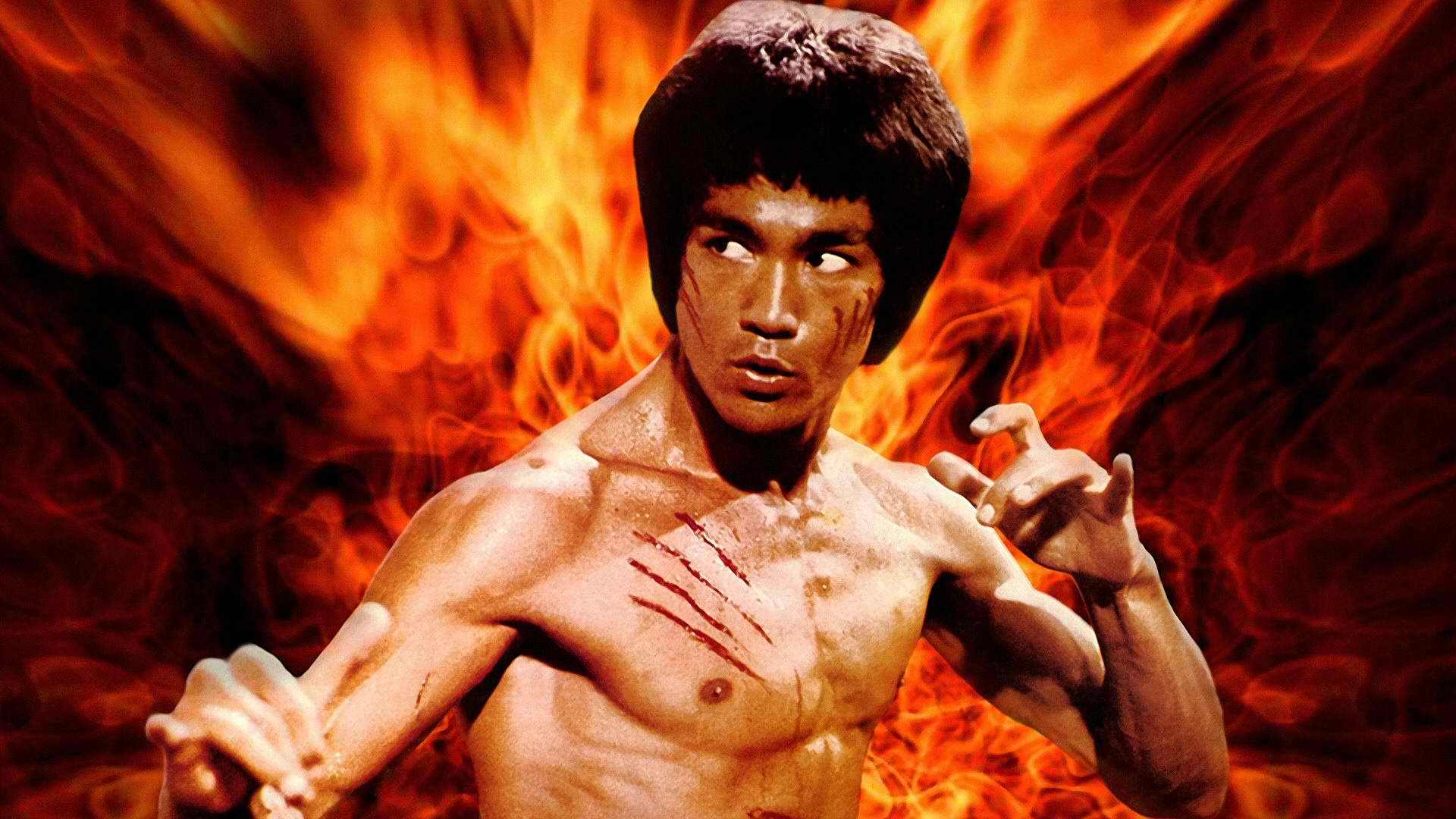

Buried on an old beta tape—relic technology from another era—it finally resurfaced, restored and preserved for the world to hear. What it contains is rare and invaluable: Jackie Chan speaking openly about Bruce Lee, not as a myth or symbol, but as a man, a mentor, a pressure-soaked human being, and the standard no one could ever truly replicate.

What emerges isn’t just a tribute. It’s a philosophy of martial arts, filmmaking, and identity.

Jackie Chan makes one thing clear early: Bruce Lee wasn’t great just because he could fight.

Plenty of martial artists were technically excellent. Many classic kung fu films were impressive, disciplined, and beautifully choreographed. But something was missing.

Bruce Lee had soul.

“He wasn’t just block, punch,” Jackie explains. “He had rhythm. Tempo. Feeling.”

Lee’s movements weren’t mechanical. They breathed. They flowed. His fighting carried personality—small feints, subtle shifts, expressive timing. It wasn’t about copying poses or screams or facial expressions. It was about understanding rhythm and energy.

According to Jackie, that was the mistake many filmmakers made after Bruce Lee’s death. They copied the surface—yells, stances, poses—without capturing the essence underneath.

“You have to look beyond that,” he says. “It was about the rhythm.”

Martial Arts Acting, Not Just Martial Arts

Jackie draws a sharp line between being competent and being great.

You can act.

You can fight.

But greatness requires something more.

“There’s a level of martial arts performance on screen,” he explains. “You can be good, and you can be great.”

Technology can enhance action, but it can’t replace real emotion expressed through physical ability. That’s why Bruce Lee’s performances still resonate decades later. His fighting wasn’t just violence—it was character, intent, and presence.

Physicality, Jackie insists, is emotion.

Meeting Bruce Lee: The Man Behind the Legend

Jackie first encountered Bruce Lee not as a star, but as a stuntman.

At the time, Jackie was one of the best stunt performers in Hong Kong. When a production needed someone to double for a Japanese actor crashing through a window, they called him. After the stunt, Bruce Lee approached him, hugged him, and asked his name.

“You’re good,” Bruce said.

That moment stuck.

Jackie worked on multiple Bruce Lee projects, including Enter the Dragon. He recalls Lee as kind, focused, and intensely driven—but also surrounded by pressure.

“He always wanted to be number one,” Jackie says. “Nobody could touch him.”

The Burden of Myth

As Bruce Lee’s fame exploded, so did exaggeration.

Jackie watched people inflate Lee’s abilities to superhuman levels—claiming his punches weighed hundreds of pounds, that his kicks were invisible to the human eye. Jackie didn’t participate in the mythmaking. Instead, he observed human nature.

“Human being is human being,” he says. “Not a cartoon.”

Even Muhammad Ali, even Mike Tyson—fast as they were—you could still see them move. But the myth around Bruce Lee created impossible expectations, and Jackie believes that pressure weighed heavily on him.

The Last Time Jackie Saw Bruce Lee

On Enter the Dragon, Jackie played a small but memorable role—getting hit accidentally during a stick-fighting sequence.

Bruce didn’t stop to apologize mid-take. He stayed in character until the director yelled “cut.” Afterwards, Bruce checked on him, and when more stuntmen were needed later that night, Bruce specifically kept Jackie on set so he could earn extra money.

“That’s Bruce Lee,” Jackie says. “He appreciated me.”

It was the last time Jackie ever worked with him.

When Bruce Lee died suddenly, Jackie didn’t believe it. He heard the news on the street, ran to a taxi, turned on the radio, and listened in shock.

“I was very, very shocked.”

Becoming Jackie Chan—By Not Becoming Bruce Lee

After Bruce Lee’s death, studios scrambled to create replacements.

Everyone wanted the next Bruce Lee. Jackie was pushed into imitation—new names, similar styles, forced seriousness. He hated it.

“I was embarrassed,” he admits.

Eventually, Jackie made a decision that would define his career: do the opposite.

If Bruce kicked high, Jackie kicked low.

If Bruce punched with rage, Jackie punched with humor.

If Bruce was untouchable, Jackie got hurt—on purpose.

“I let somebody punch myself,” he says. “That’s more easy.”

Comedy, pain, and vulnerability became his weapons. Films like Drunken Master and Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow changed everything. Jackie Chan wasn’t the next Bruce Lee.

He was the first Jackie Chan.

Reinventing Action Cinema

As others copied him, Jackie evolved again—moving away from pure kung fu into acrobatics, stunts, and physical danger.

Motorcycles. Windows. Skyscrapers. Fire.

He learned everything because he had to stay ahead. Over time, the comparisons stopped.

“Now nobody say I’m Bruce Lee,” he laughs. “Now they say Jackie Chan style.”

Why the West Was Different

Jackie also reflects honestly on why Western success came slower.

In Asia, his films were family events. Parents, kids, grandparents—all went together. In the West, action films were segmented by age, rating, and genre.

Long fight scenes that Asian audiences loved didn’t always translate. American audiences preferred short, explosive action. Asian audiences wanted endurance, escalation, and spectacle.

“It’s culture,” Jackie says simply.

The Legacy

Bruce Lee created the soul.

Jackie Chan expanded the language.

One brought philosophy and rhythm. The other brought humor, danger, and humanity. Together—whether directly or indirectly—they shaped martial arts cinema forever.

Bruce Lee proved what was possible.

Jackie Chan proved there was more than one way to be legendary.

News

🎰 “No, Man.” Why Dustin Poirier Will Never Squash the Beef With Conor McGregor

“So… would you say the beef has been squashed? All is good?” “No, man.” That was it. No pause. No…

🎰 When Trash Talk Turns Cinematic: How Paramount’s UFC 324 Promo Set the MMA World on Fire

At first, it looked like nothing more than standard fight-week trash talk. Paddy Pimblett was smiling.Justin Gaethje was staring straight…

🎰 UFC’s Dream Match Collapses as Justin Gaethje Derails the Patty Pimblett Hype Train

The first UFC event following the promotion’s official partnership with Paramount Plus is in the books—and almost immediately, the UFC’s…

🎰 Tom Aspinall claps back after ‘catching strays’ from Dana White over eye injury after UFC 324

Tom Aspinall appeared baffled to be the subject of one of Dana White’s infamous rants in the aftermath of UFC…

🎰 Dillon Danis joins Ilia Topuria in mocking Paddy Pimblett after UFC 324 defeat

Dillon Danis finally got one over on Paddy Pimblett last night as he watched his rival lose for the first…

🎰 UFC veteran simultaneously thanks and proves Dana White wrong by sharing post-fight bonus receipts

UFC 324 marked the start of a new system for earning post-fight bonuses inside the Octagon. Dana White hadn’t been…

End of content

No more pages to load