Clara Novak was 21 years old when her stepfather Joseph told her she had 3 weeks to disappear. It was late August 1873 in the timber country outside Duluth, Minnesota territory, and Joseph Carki had spent two years deciding that his wife’s daughter from her first marriage was a mouth he couldn’t afford to feed through another winter.

Clara’s father, Henrik Novak, had been a forestry worker before the family left Czech Republic in 1865. Henrik understood trees the way some men understood horses or weather, deeply, instinctively, with knowledge that came from generations of working forests. He’d worked the timber around Duluth for 5 years before tuberculosis took him in the winter of 1870. Clara had been 18 when he died, old enough to remember everything he’d taught her. Young enough that losing him felt like losing the ground beneath her feet.

Henrik’s widow, Anna, had remarried within a year. Joseph Carki was practical rather than cruel, a lumber camp worker who needed a wife and saw Anna as practical choice rather than romantic one. He brought no cruelty to Clara exactly, but he brought no patience either. She was another person eating his food, sleeping under his roof, and by August 1873, Joseph had calculated that the coming winter would cost him more than he could manage, with Clara included.

He gave Clara $15 and told her to find somewhere else. $15 for three years of labor she’d provided, cooking, cleaning, tending the small garden, hauling wood. She took the money without argument. Henrik had taught her many things. But perhaps the most important was that you don’t waste energy fighting battles you’re going to lose. You find another way.

Clara knew something about wood that most people in Duluth didn’t. Something her father had taught her years ago, something she’d filed away as interesting knowledge without understanding its potential for survival. Henrik had explained it during one of their winter afternoons in the workshop when he was teaching her about timber the way another father might teach a son.

Freshly cut wood is wet, dangerously, uselessly wet. When you fell a tree and cut it into logs, the wood contains 50 to 100% moisture. Sometimes more water by weight than wood. You can’t burn green wood efficiently. Most of the energy goes into evaporating the water before any useful heat is produced. A pound of dry seasoned wood produces roughly 8,000 BTU of heat. A pound of green wood produces barely 4,000. You’re burning twice the wood for the same warmth.

Seasoning is the process of drying wood to the point where it burns efficiently, getting moisture content down to 15 or 20%. The conventional method was simple. Stack wood outdoors in a sheltered location and wait 6 months minimum, 12 months better. The wood sat exposed to air. Moisture evaporated slowly and eventually the wood was dry enough to burn properly.

The problem, Henrik had explained, was that outdoor seasoning in Minnesota was nearly impossible to do well. Rain and snow kept rewetting the wood. Freezing temperatures in winter could actually damage wood fibers when moisture inside the logs froze and expanded, cracking the wood internally in ways that made it burn poorly even after it dried. Most families dealt with the problem by cutting enormous quantities of wood in summer and burning through winter stocks that were partially wet, inefficient, wasteful.

Henrik had seen a better system in Czech Republic used by foresters who needed reliable dry wood through brutal winters. You seasoned the wood underground in a tunnel dug into a hillside. The constant underground temperature prevented frost damage. An air channel through the tunnel driven by the natural slope created continuous air flow that removed moisture from the wood steadily and consistently. The result was perfectly seasoned wood in 4 to 6 weeks, a fraction of the time outdoor seasoning required.

Clara remembered this conversation clearly. Remembered Henrik sketching the tunnel design on the back of a feed receipt. Remembered asking why they didn’t do it that way. Henrik had smiled and said they might someday when they had a proper hillside.

They never did.

But now Clara had something Henrik never anticipated. She had a hillside. She had $15. and she had the desperate need to make them work.

She found unclaimed land two miles outside Duluth, 5 acres on the side of a glacial ridge that nobody wanted because the soil was poor and the slope made farming impossible. The very thing that made it worthless for farming made it perfect for what Clara needed, a hillside, a consistent slope from bottom to top, natural ground that she could dig into from the side rather than excavating from above.

She staked her claim in early September. Built a small one room cabin on the flatter ground at the base of the ridge. Rough-hewn timber construction, simple peaked roof, single fireplace, maybe 140 square ft of living space. The cabin took 2 weeks to build and cost about $8 of her $15 budget, functional, but crude. Not the point, anyway. The point was the hillside behind the cabin. That was where the real work would happen.

Clara spent the rest of September studying the hillside before she dug a single inch. Henrik had been precise about the design requirements. The tunnel needed to face a specific direction. The slope needed to be steep enough to drive air flow, but not so steep that the tunnel would be unstable. The entrance needed to be positioned where it would get adequate air movement without being exposed to direct wind that would overwhelm the system.

She selected a spot on the ridge where the slope ran roughly north to south, the lower end facing south, the upper end facing north. This mattered. The south-facing lower entrance would receive more solar warming during the day, creating temperature differential with the shaded north-facing upper vent. The temperature difference would drive air movement through the tunnel. Warm air rises, cold air sinks. The system would move air continuously, passively without any mechanical help.

The excavation began in early October. Clara dug horizontally into the hillside at the base of the slope, not down from the top like a well or a root cellar, but sideways into the earth like a mine entrance. The tunnel would extend 18 ft into the hillside, following the natural slope upward at a gentle angle.

The Minnesota glacial till she was digging through was a mixture of clay, sand, gravel, and occasional boulders left by retreating glaciers thousands of years earlier. Harder than loose soil, but softer than solid rock. She used a heavy spade and a pickaxe, working methodically through the material. Each spadeful weighed perhaps 12 to 15 lb. Each foot of tunnel required removing roughly 30 cubic feet of earth, hundreds of individual spadefuls.

The work was brutal. Clara weighed perhaps 105 lb and stood 5’4″. She was strong from years of farm labor, but this excavation was beyond anything she’d done before. She’d work dawn to dusk, breaking ground methodically, hauling excavated earth out in buckets and a wheelbarrow. By evening, her hands were raw, her back screaming. Her clothes soaked through with sweat despite the October cold.

She shaped the tunnel as she dug. The cross-section was roughly oval, 6 feet wide at the base, narrowing to about 4 feet at the top, 5 1/2 ft high at the center, enough space to stand upright in the middle, crawl the edges. The floor was leveled carefully, not perfectly flat, but smooth enough to roll logs across.

The walls needed reinforcement. Raw earth would collapse, especially with frost cycles expanding and contracting the soil. She lined the tunnel walls with rough-hewn timber planks, vertical boards set against the earth walls held in place by horizontal cross beams every 2 ft. The cross beams were notched into the tunnel walls locked against the earth itself. The timbers created a stable shell within the earth and tunnel.

The ceiling was the most critical element. She built it from heavy timber beams, 4 in x 6 in planks laid side by side across the tunnel width every 2 ft, creating a solid ceiling that could support the earth above. Between the beams, she packed clay tightly. This sealed the ceiling against moisture seepage while allowing the earth above to provide insulation.

The excavation and timber lining took 3 weeks of sustained work. By late October, the tunnel was complete, 18 ft long, bored into the hillside at a gentle upward angle, timber-lined with a clear entrance at the base of the slope.

The two vents were the heart of the system. The lower entrance at the base of the hillside facing south was simply the tunnel opening itself. Clara built a sturdy timber frame around it and fitted a door that could be opened or closed. When open, air could flow freely into the tunnel.

The upper vent was different. At the far end of the 18 ft tunnel, where it penetrated deepest into the hillside, Clara dug a small vertical shaft upward through the earth to the surface, 8 in square, lined with timber, rising about 4 ft to break through the ground surface on the upper part of the slope. This shaft was the exhaust vent, the point where air leaving the tunnel escaped to the outside.

The physics were elegant and simple. The lower entrance faced south, received more solar warming, was slightly warmer. The upper vent was shaded, slightly cooler. Warm air rose. Cool air sank. Air flowed continuously from the lower entrance through the tunnel and out the upper vent, driven by nothing more than the temperature difference between the two openings. No fan, no pump, no mechanical anything, just gravity and thermodynamics working together.

Clara tested the system by lighting a small smoke fire near the lower entrance. The smoke drifted into the tunnel, moved through it slowly but steadily, and emerged from the upper vent on the hillside above. The airflow was real, gentle, maybe a few feet per second, but continuous and consistent, enough to carry moisture away from anything stored inside.

She began filling the tunnel in late October, cutting trees from the ridge and carrying the logs down to the entrance. Fresh green logs, unseasoned, heavy with moisture, practically dripping sap if you cut them wrong. She carried them in pairs, rolling them down the hillside, maneuvering them through the entrance, positioning them inside the tunnel on simple timber racks she’d built to hold logs off the floor.

The racks were important. Henrik had been specific about this. Wood needed air circulation on all sides to season evenly. Logs sitting directly on the ground would retain moisture on the bottom, develop mold on the contact surface, season unevenly. The racks held logs 6 in above the floor, allowing air to flow beneath them, as well as around and above.

She filled the tunnel with perhaps two cords of green wood, roughly 120 cubic feet of logs stacked on the racks. The tunnel was full, but not packed. She left gaps between logs for air movement. The system needed breathing room to work. Then she closed the lower entrance door, not sealed, just closed, left the upper vent open and waited.

The first two weeks, nothing visible happened. The logs sat in the tunnel, green and heavy, looking exactly as they had when she’d carried them in. Clara checked every few days, would open the entrance door, reach into the wood, feel the surface, still damp, still heavy, still green. But something was happening that she couldn’t feel yet. The air flowing through the tunnel was carrying moisture away from the wood surface, one invisible layer at a time.

The constant temperature inside the tunnel, about 40°, never freezing, never warming, meant the moisture was evaporating at a consistent rate rather than the uneven drying that happened outdoors. The wood fibers weren’t contracting and expanding with temperature swings. The moisture was leaving cleanly, steadily, without damage.

By the end of the third week, Clara noticed the change, reached into the tunnel, and touched a log. The surface was drier, not dry, but noticeably less damp than it had been. The smell had shifted, too. The sharp green sap smell was fading, replaced by the warmer, woodier smell of drying timber.

By week four, the transformation was unmistakable. The logs had lost significant weight, she could tell by lifting one end. The surface was dry to the touch. The wood had taken on the lighter color of seasoned timber. She split one log with her axe to check the interior. The cross-section showed wood that was perhaps 60% of the way to fully seasoned. Moisture content dropping steadily.

By week six, the wood was done. Fully seasoned, 15 to 20% moisture content. Clara split a test log and held a match to a chip. It caught immediately, burned hot and clean with none of the sputtering and smoke that green wood produced. 8,000 BTU per pound, efficient, powerful heat from wood that had been dripping with sap six weeks earlier.

She carried the seasoned logs out of the tunnel and into her cabin, built a fire in the fireplace. The wood burned beautifully, hot, clean, steady. One log produced more useful heat than three green logs would have. Her small cabin warmed quickly, maintained comfortable temperature with minimal wood consumption.

The neighbors noticed something strange about Clara’s property almost immediately, though they couldn’t have articulated exactly what it was. There was no wood pile. Every other homestead in the Duluth area had a wood pile. Stacks of logs and split wood visible from the road, growing through summer and shrinking through winter. Clara’s property had nothing. A small cabin, a tool shed, and bare ground. No wood anywhere visible.

They watched her cutting trees on the ridge throughout September and October, saw her hauling logs down the hillside, but the logs disappeared. No stacking, no splitting into firewood, just green logs carried to the base of the ridge and vanishing behind the cabin where the hillside rose.

Elsa Brandt was the first to say what everyone was thinking. Elsa was wife of Hinrich Brandt, who owned the general store and lumberyard in Duluth. She was 43, sharp-tongued and accustomed to being right about practical matters. She organized a visit in mid-November with four other women from the area. Concerned citizens checking on the young Czech woman who seemed to have no firewood heading into winter.

They arrived on a gray November afternoon, wind cutting across the ridge. Clara invited them inside the cabin. The fireplace was burning, the cabin warm, maybe 58°, comfortable enough. The women looked around for the wood pile visible through the window. Found nothing.

“Where is your firewood?” Elsa asked bluntly. “We’ve watched you cutting trees for 2 months, but there’s no wood anywhere on your property. No pile, no stack, nothing split. How are you burning this fire?”

Clara gestured to the stack of seasoned logs beside the fireplace. Maybe 20 logs, enough for a week. “I bring it in as I need it.”

“From where? There’s nothing outside.”

“From the hillside.”

“All the hillside is bare ground and rock.”

Clara considered how much to explain, decided on directness. “I have a storage tunnel dug into the hillside. The wood is stored inside. It stays dry. I bring it out when I need it.”

Elsa’s expression shifted from confusion to something approaching pity. “A tunnel in the hillside. You’re storing firewood in a hole in the ground. That wood will be completely rotted by spring. The ground is damp. Underground is damp. Wood rots in damp conditions. You’re going to run out of firewood and freeze.”

“The tunnel has air flow. The wood stays dry.”

“Air flow in a hole in the ground. Miss Novak, I think you don’t understand how wood storage works. You need a proper woodshed with a roof and good drainage. What you have will kill you. Please let us help you find proper arrangements before winter gets serious.”

Clara thanked them for their concern. Watched them leave through the window, certain she would be dead or desperate by December.

Through November and into December, Clara’s system worked exactly as Henrik had designed it decades before in Czech Republic. She’d cut fresh trees, carry the green logs into the tunnel, position them on the racks. Six weeks later, she’d bring out perfectly seasoned wood. The rotation was continuous, new green wood going in while older batches came out seasoned. The tunnel always contained wood at various stages of drying.

Her fuel consumption was remarkable because every log she burned was perfectly seasoned. Each log produced maximum heat. She burned perhaps a cord and a half through November and December, roughly half what her neighbors were burning. And her neighbors were burning inefficiently because most of their wood was green or poorly seasoned from hasty outdoor drying. They were watching their wood piles shrink at alarming rates while Clara’s cabin stayed consistently warm.

The economics were devastating for comparison. Hinrich Brandt’s lumber yard sold seasoned firewood at $2 per cord, but most of it was only partially seasoned, dried perhaps 4 months outdoors. Clara’s wood was better seasoned than anything for sale in Duluth, and it cost her nothing but labor to produce.

December brought the first real cold. Sustained temperatures in the 20s at night, single digits during the worst days. Clara’s cabin maintained 55 to 60° with moderate fire burning. Her neighbors cabins fluctuated wildly as they fed green wood into fireplaces that sputtered and smoked and produced disappointing heat.

The Brandt household went through three cords of wood in December alone. Hinrich burned constantly, frustrated that his expensive firewood wasn’t heating properly. Elsa complained about the smoke, the smell, the inefficiency. They had six more cords stacked outside, enough for January and February if consumption stayed steady. But it wouldn’t. The cold was going to get worse.

January brought the storm that broke everything open. The blizzard hit January 19th with brutal suddenness. Temperature plummeted from 15° to minus 25 overnight. Wind screamed across the ridge at sustained 45 mph. Snow fell in dense curtains for eight consecutive days. Conditions that tested every heating system in the region to the point of failure.

Clara’s cabin stayed warm. The fireplace burned steadily with perfectly seasoned logs, each one catching immediately, burning hot and clean, producing consistent heat. She’d brought in two weeks worth of wood before the storm hit. Knowing from the sky and the wind that something catastrophic was coming, Henrik had taught her to read weather, too.

The Brandt household began struggling by day two. Hinrich was burning wood desperately. Green wood that sputtered, smoked, produced half the heat it should have. The fireplace roared constantly, but the cabin temperature kept dropping. 45° by evening, 40 by midnight. The green wood simply couldn’t produce enough heat to overcome the cold driving in through every gap.

By day three, other families were worse off. The Patterson cabin ran out of seasoned wood entirely on January 21st, left with nothing but green logs cut 2 weeks earlier that barely burned at all. The family huddled in blankets around a fire that produced more smoke than heat. Their children showed signs of cold exposure despite being indoors. Pale skin, shivering that wouldn’t stop, confusion.

On day four, Hinrich Brandt made the decision that would reveal Clara’s secret to the entire community. He’d heard rumors, vague, confused reports that Clara’s cabin was somehow staying warm while everyone else was struggling, that she had wood that burned properly when nobody else did. He walked through the blizzard to her cabin 2 mi through knee-deep snow and minus 25 wind to find out how.

Clara opened the door. Hinrich stumbled in, frost-covered, breathing hard, looked around at the cabin, warm, comfortable, fireplace burning steadily with wood that glowed orange-red with efficient heat. Looked at the stack of logs beside the fireplace. The wood was clearly dry, the pale golden color of properly seasoned timber, no visible moisture, bark peeling slightly the way good, dry wood does.

“How?” Hinrich said, still catching his breath. “How is your wood burning like that? I’ve been burning for 4 days straight and my house is 40°. Your wood is burning like it came from a kiln. Where did you get this wood?”

“I seasoned it underground in a tunnel in the hillside.”

“Show me.”

Clara pulled on her coat and led Hinrich around the back of the cabin to the hillside. The entrance was there. She’d built a sturdy timber door frame set into the earth, nearly invisible when the door was closed because the natural hillside soil and vegetation blended around it. She opened the door and led Hinrich inside.

He stopped at the entrance, staring. The tunnel stretched 18 ft into the hillside, lit by a single oil lamp. Clara carried timber-lined walls, solid timber ceiling, and everywhere on the racks, on the floor, stacked against the walls, logs, dozens of logs, all of them dry, bone dry, the golden color of perfectly seasoned wood filling the tunnel completely.

“This is impossible,” Hinrich said slowly. “This wood is underground. Underground is damp. This should be rotted, but it’s drier than anything I’ve ever seen.”

Clara explained the system, the slope-driven convection, the lower entrance warming from sun, the upper vent staying cool in shade, the natural air flow carrying moisture away from the wood continuously, the constant temperature preventing frost damage, the 6 week seasoning time.

“You put green wood in here and it comes out dry in 6 weeks.”

Hinrich touched a log, ran his fingers along the surface, completely dry, knocked on it with his knuckles. The hollow sound of properly seasoned timber, not the dull thud of wet wood.

“Green wood in, seasoned wood out, the hillside does the work. I just carry it in and carry it out.”

Hinrich stood in the tunnel for a long time, understanding washing over him. He ran a lumber yard, had sold wood for years, had never in all his years in the timber industry, seen wood seasoned this cleanly, this completely, this quickly. Clara Novak, 21 years old, expelled from her stepfather’s house with $15, had built a wood seasoning system that outperformed anything available commercially in Duluth.

“How much wood do you have?” he asked.

“About two and a half cords seasoned and ready. Another cord and a half at various stages of drying.”

“I need wood. My house is 40°. The Patterson’s children are hypothermic. Half the families in the area are running out or burning garbage because their wood won’t burn. How much can you spare?”

Clara looked at the tunnel full of wood. Looked at Hinrich, a man whose wife had come to her cabin weeks ago, convinced she’d freeze to death, a man who ran a lumberyard and had never considered underground seasoning.

“Take what you need,” she said. “Take enough for the Pattersons, too. Enough for anyone who needs it.”

By the end of day four, 12 families had sent someone to Clara’s tunnel. They came through the blizzard through minus 25 wind and knee-deep snow because their firewood wouldn’t burn and their houses were dropping below survivable temperature. Each family that entered the tunnel had the same reaction. Shock at the dry wood, confusion about how underground storage could produce drier wood than outdoor storage. Then understanding slowly as Clara explained the convection system.

The word spread even through the blizzard. By day five, families were sending children, teenagers who could trudge through the snow faster to carry dry seasoned logs back from Clara’s tunnel. The wood burned magnificently in their fireplaces. One cord of Clara’s seasoned wood produced more heat than two cords of the greenwood they’d been burning. Houses that had been dropping steadily toward dangerous temperatures began warming again.

Elsa Brandt came herself on day six. trudged through the blizzard to Clara’s cabin, entered the tunnel, watched other families loading up seasoned logs, stood in the 18-ft tunnel surrounded by wood that should have been rotting underground, but was instead the driest, cleanest firewood anyone in the area had ever seen.

“I told you this would rot,” Elsa said quietly, almost to herself. “I told you underground was damp. I was wrong.”

“You were thinking about a simple hole,” Clara said. “No air flow, no drainage, just earth and wood sitting together. That would rot. This is different. The slope drives air through continuously. The wood dries faster underground than it would outdoors because the temperature never freezes the moisture inside. Henrik, my father, learned this in Czech Republic. Foresters used it for generations.”

“Your father taught you this.”

“He taught me everything about wood. I just needed a hillside to use it.”

Elsa looked at Clara for a long moment. The young woman her delegation had visited 6 weeks earlier, pitying her for her foolishness, certain she’d freeze. The young woman whose cabin had no visible firewood, and whose neighbors had assumed she was doomed, standing in a tunnel full of the best firewood any of them had ever burned, explaining a system that had been keeping her warm while they suffered.

“I’m sorry,” Elsa said, “for the visit, for what we said. We assumed you were stupid because you were young and alone and doing something we’d never seen. We were wrong.”

Clara nodded. “My father wasn’t stupid. He was a forestry worker in Czech Republic. He understood trees better than most people understand anything. I just remembered what he taught me when I needed it most.”

The blizzard ended January 27th. 8 days of sustained minus 25 and 45 mph wind. When it broke, the community emerged to find that Clara’s underground tunnel had been the difference between survival and disaster for a dozen families.

Hinrich Brandt came back after the storm with a proposition. He wanted to understand the system thoroughly. Wanted to build similar tunnels for the lumber yard, season wood underground for commercial sale. The wood would command premium prices. He offered Clara consulting work, payment for explaining and helping design the tunnels. Clara accepted, not because she needed the money. She’d survived on $15 and her own labor, but because spreading the knowledge mattered more than keeping it private. Henrik had learned the system from generations of Czech foresters who’d shared it freely, Clara would do the same.

By spring 1874, three underground seasoning tunnels had been built on hillsides around Duluth using Clara’s specifications. Each one produced perfectly seasoned firewood in 6 weeks. Hinrich Brandt’s Lumberyard began selling underground seasoned wood at premium prices. Customers could feel the difference immediately when they burned it.

Clara lived on her 5 acres for 7 years. The tunnel she built in 1873 continued functioning. She’d fill it with green wood, wait 6 weeks, bring out seasoned wood. The system never failed. The hillside did the work. She just managed the process.

She married at 24, a timber worker who’d watched her tunnel system work through two winters and understood exactly what he was getting in a wife. They expanded the property, built a proper house, kept the original tunnel functioning alongside two larger ones they built together.

Clara died in 1931 at age 79. The Duluth Historical Society documented her tunnel system after her death. The original 18 ft tunnel still intact in the hillside, timber-lining sound after 58 years, the slope-driven vent system still capable of seasoning wood if someone filled it.

Modern forestry engineers confirmed what Henrik Novak had understood decades before arriving in America. Underground seasoning tunnels on proper slopes produce wood dried to 15% moisture content in four to 6 weeks, a fraction of the time required for outdoor seasoning. The constant temperature prevents freeze-thaw damage to wood fibers. The slope-driven convection removes moisture consistently without mechanical assistance. The system is passive, maintenance-free, and produces results superior to any outdoor seasoning method.

The story is about a young woman who remembered what her dead father taught her and used it to survive. Who built something that looked like nothing from the outside, a hole in a hillside, but was actually sophisticated engineering based on generations of forestry knowledge, who kept her neighbors alive during a blizzard with wood that nobody believed could exist underground.

Because sometimes the person with no visible firewood knows more about keeping wood dry than the man who runs the lumberyard. The tunnel everyone called a hole in the ground was actually a seasoning system that outperformed anything on the market. And a father’s knowledge carried in a daughter’s memory across an ocean in 20 years can be worth more than $15 and a hillside.

News

My Wife Went To The Bank Every Tuesday for 20 Years…. When I Followed Her and Found Out Why, I Froze

Eduardo Patterson was 48 years old and until 3 months ago, he thought he knew everything about his wife of…

Her Father Lockd Her in a Basement for 24 Years — Until a Neighbor’s Renovation Exposed the Truth

Detroit, 1987. An 18-year-old high school senior with a promising future, vanished without a trace. Her father, a respected man…

“Choose Any Daughter You Want,” the Greedy Father Said — He Took the Obese Girl’s Hand and…

“Choose any daughter you want,” the greedy father said. He took the obese girl’s hand. Martha Dunn stood in the…

Her Son Was Falsely Accused While His Accuser Got $1.5 Million

He was a 17-year-old basketball prodigy. College scouts line the gym. NBA dreams within reach. But one girl’s lie shattered…

🎰 Four Flight Attendants Missing for 26 Years… Until Construction Broke the Wall

In 1992, four flight attendants walked into Dallas Fort Worth International Airport for a routine overnight shift and were never…

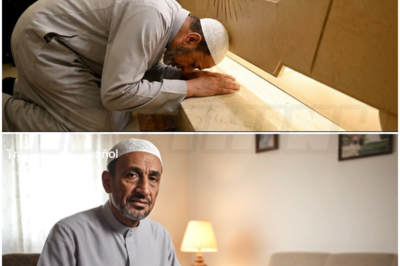

🎰 A Muslim Man Went Out Of Curiosity To The Tomb Of Saint Carlo Acutis… And Everything Changed After…

“The first time I entered that Catholic church in Assisi, I was wearing my white kufi and gray thobe, because…

End of content

No more pages to load