October 1944. The Herkin Forest.

A German patrol laughed when they saw him. An Apache Scout. No boots, no map, just silence. By dawn, 12 soldiers had vanished without a single shot fired. This is the story of how ancestral knowledge became the deadliest weapon of World War II, and why an entire Vermacht unit learned too late that some wars are won before the enemy even knows they’re being hunted.

The morning mist clung to the trees like cigarette smoke trapped in a closed room. Sergeant William Cartwright stood outside the command tent watching as Captain Robert Harrison briefed the new arrivals. Two men, Native Americans, one wore his uniform like it was borrowed. The other moved like the forest itself had taken human form.

Cartwright had seen plenty of soldiers in his two years of combat. He’d seen farm boys from Iowa turn into hardened killers. He’d seen college graduates break under artillery fire. He’d seen men who looked tough crumble and men who looked weak become heroes. These two didn’t fit any category he knew. They didn’t walk like soldiers. They walked like they were reading something invisible in the air, like every step was a conversation with the ground beneath their feet.

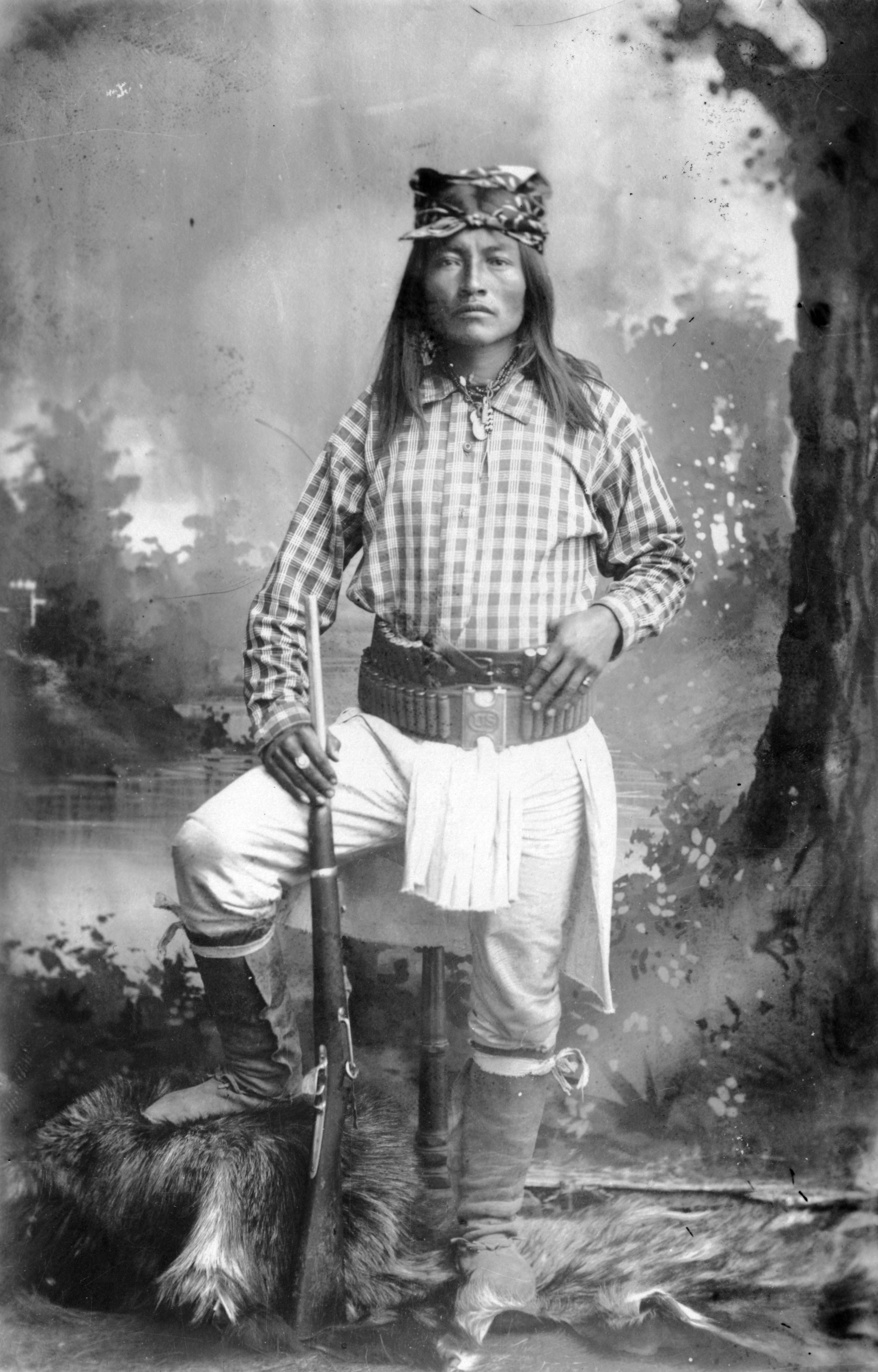

Captain Harrison gestured toward the taller one, Joseph Nicha, Apache. The name meant nothing to Cartwright at first. Later he’d learned that Nicha was descended from chiefs, from warriors who’d held off the entire United States Army for decades using nothing but knowledge of the land and absolute refusal to surrender. The other was Thomas Big, Navajo. His people had walked the long walk, survived forced relocation, kept their culture alive through generations of suppression.

Harrison called them scouts. Cartwright called them a waste of resources. The Germans were dug in 5 mi east. Mortars, machine gun nests, veteran troops from the Eastern Front who’d seen hell in Stalingrad and come back meaner. And command sent two Indians with no boots and no rifles. Cartwright lit a cigarette and turned away. This was going to be a disaster. He’d seen enough disasters. Normandy had been a disaster. The hedgerows had been a disaster. Now this forest, this endless maze of trees and mud and death, was shaping up to be the biggest disaster yet.

That afternoon, intelligence reported movement. A German patrol, 12 men. Lieutenant Marcus Hoffman leading. Hoffman was known throughout the Allied intelligence network. Ruthless, experienced, calculating. He’d survived Stalingrad when 90% of his division had frozen or starved or been shot. He’d held positions in Normandy when everyone else retreated, buying time for German forces to regroup. He was the kind of officer who didn’t make mistakes, who didn’t underestimate enemies, who treated war like chess played with human lives. Now he was here in the Herkin, hunting American forward positions, probing for weaknesses, gathering intelligence for the coming German counter-offensive that would later be known as the Battle of the Bulge.

Captain Harrison called Joseph and Thomas into the tent. Cartwright followed, curious in spite of himself. Harrison spread the map across the table, his finger tracing the reported route. Hoffman’s patrol was moving through sector 7. Dense forest, no roads, no clearings. Perfect ambush territory if you knew what you were doing. Perfect death trap if you didn’t.

Harrison looked at Joseph. “Can you track them?”

Joseph didn’t look at the map. He looked at Harrison with eyes that seemed to see through the canvas walls, through the trees, through time itself. “We don’t need to track them. We need to make them track us.”

Cartwright laughed. It came out harsher than he intended. “That’s your plan? Get them to follow you. You’re going to leave a trail for veteran Wehrmacht soldiers and hope they’re dumb enough to follow it.”

Thomas spoke for the first time, his voice quiet, but carrying absolute certainty. “They won’t know they’re following. They’ll think they’re hunting. They’ll think they found our trail by skill. By the time they realize the truth, it’ll be too late.”

Cartwright shook his head. This was insane. This was suicide. This was going to get good men killed.

Harrison nodded slowly. “Do it. And Cartwright, you’re going with them.”

Cartwright’s cigarette nearly fell from his lips. “Sir?”

Harrison’s expression left no room for argument. “You’re going to watch. You’re going to learn. And you’re going to report back exactly what you see. That’s an order.”

They left at dusk. Joseph, Thomas, Cartwright, and Private Roscoe Whitmore, a kid from Tennessee who couldn’t stop talking even when silence might save his life. Roscoe kept asking questions as they geared up.

“How do you track without a map? How do you see in the dark? Do you really not wear boots?”

Joseph never answered, just checked his equipment with methodical precision. Thomas smiled once, a slight curve of his lips that suggested he’d heard these questions a thousand times before. “You don’t see in the dark. You listen to it, you feel it, you become part of it.”

Roscoe went quiet after that, but his eyes stayed wide, watching everything the two scouts did.

They moved through the forest like shadows given human form. No flashlights, no noise, no wasted movement. Cartwright had been in combat for 2 years. He’d done night patrols in North Africa. He’d crawled through hedgerows in France under German flares. He thought he knew how to move silently. But watching Joseph and Thomas, he realized he’d been stomping through every forest he’d ever entered like a drunk elephant. They didn’t step on branches. They didn’t disturb leaves. They didn’t even seem to breathe loudly. It was like watching ghosts, like watching something that existed between the physical world and somewhere else entirely. Every step was placed with absolute precision. Every movement flowed into the next. They didn’t fight the forest. They became it.

After an hour of moving through darkness so complete that Cartwright could barely see his own hands, Joseph stopped. He crouched, his fingers touching the ground with the delicacy of a surgeon. Cartwright saw nothing. Just dirt. Just leaves. Just the same forest floor they’d been crossing for an hour.

Joseph stood slowly. “They were here 3 hours ago. 12 men. One is injured. Left leg favoring it heavily. Probably twisted it in a hole. He’ll slow them down. Make them irritable. Make them careless.”

Cartwright stared. “How the hell do you know that? How can you possibly know that from looking at dirt in the dark?”

Joseph pointed at a slight depression in the soil, barely visible even when Cartwright focused directly on it. Then at a broken twig snapped at an angle that apparently meant something. Then at a smear on a rock that could have been anything. “Bootprint. See the depth difference? Left side deeper than right. That means weight shifted away from the left leg. And here… blood on the stone. Not much, just a seep through the boot from a blister or a cut, but enough to know he’s hurting.”

Thomas knelt beside a tree, his fingers tracing something on the bark that Cartwright couldn’t see even when he looked directly at it. “They’re confident. Not watching their flanks, moving in a straight line, no counter-tracking, no false trails. They think they own this forest. They think they’re the predators here.”

Joseph nodded. “Let’s teach them they don’t. Let’s teach them what it means to enter land that doesn’t want them.”

Two miles east, Lieutenant Marcus Hoffman sat on a fallen log, cleaning his rifle with practiced efficiency. His men were spread out in a defensive perimeter, each positioned to cover approaches and support each other. It was textbook. It was professional. It was what had kept him alive through 3 years of war.

Corporal Heinrich Müller was smoking, talking too loud as usual, his voice carrying through the night air like a beacon. Müller had seen the intelligence reports. American scouts, Indians, Native Americans brought in from reservations to track German patrols. He’d laughed when he read it. A harsh bark of derision that made the other men look up.

“Primitives. Savages with no training, no discipline, no understanding of modern warfare. What are they going to do? Track us with smoke signals?”

The men laughed. Even Private Wendelin Gottschalk, the youngest of the group at barely 19, grinned despite his nervousness. Wendelin had only been with the unit for 3 weeks, transferred in as a replacement after the original soldier had been killed by American artillery.

Hoffman didn’t laugh. He’d fought Russians on the Eastern Front. He’d fought partisans who melted into the countryside like water into sand. He’d seen what happened to German patrols who underestimated local knowledge, who assumed that modern training and superior equipment would always win. He knew better than to underestimate anyone, especially people who’d been surviving on hostile land for generations.

But Müller kept talking, his voice growing louder with each drag on his cigarette. “They send Indians to fight us. What’s next? Cowboys and horses? Maybe they’ll lasso us.”

The men laughed again, tension easing in the familiar comfort of mockery. Even Hoffman allowed himself a slight smile. Morale mattered. Confidence mattered. But he still watched the trees, his instincts screaming that something felt wrong. The forest was too quiet. The normal sounds of night, the insects and small animals and wind through leaves had gone silent. In his experience, forests only went silent for two reasons. Predators or soldiers.

Joseph and Thomas moved into position half a mile ahead of the German patrol. Their movements invisible in the darkness. Cartwright and Roscoe stayed back, hidden in a thicket so dense that Cartwright felt like he was being swallowed by vegetation. Cartwright watched through binoculars as Joseph did something strange. He broke branches, not randomly, but deliberately at eye level where they’d be easily spotted. Then he disturbed the soil, dragging his boot in a clear line toward the west. Then he scattered some equipment, a canteen cap, a piece of torn fabric. Then he did something that made Cartwright’s blood run cold.

He disappeared.

Not walked away. Not crept into shadows. Disappeared. One second Joseph was standing in a small clearing, clearly visible in the faint moonlight. The next second, nothing. Empty space. Cartwright blinked, rubbed his eyes, looked again. Still nothing.

Roscoe whispered beside him, his voice shaking slightly. “Where’d he go? I was looking right at him.”

Cartwright scanned the area with the binoculars, checking every shadow, every tree, every possible hiding spot. Nothing, no movement, no shadow that seemed out of place, no human shape. It was like Joseph had evaporated, like he’d been a ghost all along and had simply chosen to stop being visible.

Then Thomas did the same. Broke a branch, left a footprint, scattered a cigarette butt, vanished.

Cartwright felt a chill run down his spine despite the warm night air. If he hadn’t seen them enter that clearing with his own eyes, watched them create the false trail, he’d never know they were there. He’d walk right past them, right over them, maybe. And if they could disappear like that completely and totally, what could they do to an enemy patrol? What could they do to soldiers who didn’t even know they were being hunted?

Roscoe’s whisper came again. “This is impossible. People can’t just vanish.”

Cartwright didn’t answer. He was beginning to realize that everything he thought he knew about combat, about tactics, about warfare itself was about to be challenged.

Dawn came cold and gray, the sun struggling to penetrate the thick canopy overhead. Hoffman’s patrol moved west, following the trail that Müller had spotted just after first light. Müller had been excited, energized by the find. Broken branches, footprints, scattered equipment, signs of movement that any trained soldier could read. He grinned at Hoffman.

“Told you. Amateurs. They don’t even cover their tracks. Probably reservation Indians who’ve never seen real combat. This will be easy.”

Hoffman studied the trail carefully. His experienced eyes taking in every detail. It was too clear, too obvious, too perfect. He’d seen this before. In Russia, partisans would leave trails. Obvious trails that any German soldier could follow. Trails that led straight into kill zones where machine guns waited or where the ground had been mined. He’d lost good men to those trails.

He raised his hand. The patrol stopped instantly, weapons coming up, eyes scanning the trees.

Müller looked confused. “What’s wrong? We’ve got a clear trail. We can catch them before noon.”

Hoffman scanned the trees slowly, methodically, looking for anything out of place. “This is bait. This is a trap. No experienced soldier leaves a trail this obvious unless they want it followed.”

Müller laughed, but there was an edge to it now. “Bait from Indians? Sir, with respect, they probably don’t even know we’re here. They’re probably running scared, dropping equipment as they go. This is an opportunity.”

Hoffman wanted to turn back. Every instinct screamed at him to turn back, to return to base, to report the trail and let someone else deal with it. But orders were orders. Command needed intelligence. Needed to know American positions. Needed to probe for weaknesses before the coming offensive.

He signaled the patrol forward. “Slowly. Weapons ready. Stay alert. Watch the flanks. This feels wrong.”

They walked for 2 hours, the trail continuing ahead of them like a breadcrumb path through a fairy tale, clear, consistent, leading them deeper into the forest, away from their base, away from support, into territory that grew denser and darker with each step. Hoffman’s unease grew with every mile. The forest was too silent. No birds sang, no insects buzzed, just the sound of boots on soil and the occasional whisper of wind through branches that sounded almost like voices.

The men felt it, too. Conversation died. Jokes stopped. Even Müller grew quiet, his eyes darting to the shadows between trees.

Then the trail split. One set of tracks went north into a narrow ravine. Another went west toward higher ground. Hoffman stopped, studying both paths. This was a decision point, a test.

Müller moved to the northern trail, kneeling to examine the tracks. “This one looks fresher. The prints are deeper. They went this way recently. We should follow this one.”

Hoffman shook his head slowly. “We split up. Six men north, six men west. We cover both trails. We regroup at the ridge in 4 hours. If either group makes contact, fire three shots. The rest converge on that position.”

Müller grinned. “Finally, some action. I’m tired of walking.”

Hoffman took the western trail. Müller took the northern. They synchronized watches, checked radios, agreed on rally points and emergency procedures. As the two groups separated, Hoffman looked back once. Müller was already out of sight, swallowed by the forest. The trees seemed to close behind him like a mouth closing. Hoffman shook off the feeling. Superstition, nothing more. He had six good men, veteran soldiers. They’d be fine.

Cartwright watched from a concealed position as the German patrol split, his binoculars tracking both groups. Joseph was beside him now, appearing so suddenly that Cartwright nearly gasped.

“When did you get here? I’ve been watching you for 10 minutes.” Cartwright hissed.

Joseph didn’t answer. He just watched the Germans with eyes that tracked every movement, every gesture, every decision. Thomas appeared on the other side, materializing from shadows like he’d been born from them. Roscoe nearly jumped, biting back a yelp.

“Jesus Christ, how do you do that? How do you move without sound, without disturbing anything?”

Thomas smiled. And for the first time, Cartwright saw something in that smile that wasn’t entirely human, something older, something that remembered when these forests belonged to people who knew every tree, every stream, every animal path.

“You move with the forest, not against it. You ask permission with every step. You become part of the breathing, living thing around you. Most soldiers fight the land, try to dominate it, control it. We join it, become it, and once you’re part of it, you can do things that seem impossible to those who remain separate.”

Joseph stood slowly, his movements fluid and controlled. “Müller’s group is ours. Six men, overconfident, following the trail we left like it’s a highway. They think they’re hunting. They have no idea they’re the prey. Hoffman’s group will loop back when they find nothing but false trails and dead ends. We take Müller first. Eliminate the aggressive element. Then we handle Hoffman. He’s smarter, more careful. He’ll be harder. But fear is a weapon, too. By the time we face Hoffman, he’ll already be defeated. He’ll have spent hours wondering what happened to Müller, wondering if he’s next. The mind destroys itself when given time and silence.”

Cartwright wanted to argue. Wanted to say this was reckless, that they should call in support. That four men couldn’t take on 12 veteran German soldiers. But he’d seen enough. Seen Joseph and Thomas disappear. Seen them read stories in dirt and broken twigs. Seen them move like they were part of the forest itself. He just nodded.

“What do you need us to do?”

Joseph looked at him with something that might have been respect. “Stay hidden. Watch. Learn. If something goes wrong, you get back to base and report. But nothing will go wrong. This forest has already chosen who survives today. And it wasn’t them.”

Müller’s group moved north, following the tracks into the narrow ravine. The walls rose on both sides, steep and covered in thick vegetation. Müller didn’t like it. Too exposed, too confined. No room to maneuver. But the tracks were fresh, clear, bootprints in soft soil, broken branches still oozing sap. They had to be close, maybe minutes ahead. He signaled his men forward with hand gestures, weapons up, safeties off. They entered the ravine in tactical formation. Three men on each side, covering angles, moving with the precision of soldiers who’d done this a hundred times before.

The tracks continued down the center of the ravine, clear as day. Then halfway through, they stopped. Just ended like whoever had been making them had been lifted into the air by invisible hands.

Müller stared at the last footprint. “What the hell? This doesn’t make sense.”

One of his men, a veteran named Schmidt, knelt beside the tracks, checked the ground carefully. “It’s like they just vanished. No scuff marks, no signs of climbing, no indication they turned around. They were here, then they weren’t.”

Müller spun around, his weapon coming up. Something was wrong. Very wrong. The ravine felt smaller now, darker. The walls seemed to lean in. He looked up at the ridge above. The treeline was thick. Shadows layered on shadows. He couldn’t see anything clearly, but he felt it—the absolute certainty that they were being watched, that eyes were on them, that something was out there in those trees, invisible, impatient, and absolutely deadly.

He opened his mouth to give the order to retreat, to get out of this death trap before whatever was waiting decided to spring.

Then the first man disappeared.

No gunshot, no scream, no sound at all. Just there one second, gone the next. Pulled backward into the brush like a fish hooked on an invisible line.

Müller shouted, his voice cracking, “Contact! Contact! Rear! Weapons up!”

But there was nothing to shoot at. No enemy, no movement, just empty space where Schmidt had been standing two seconds ago.

Another man vanished. This time, Müller saw it. Saw hands—dark and fast—reach out from vegetation that should have been too thin to hide anyone. Saw his soldier grabbed, a hand over his mouth, and pulled backward. Then nothing. Silence. The vegetation didn’t even move.

Müller fired blindly into the trees, his rifle bucking against his shoulder. His men did the same. Panic overriding training. Bullets tore through leaves and bark. Ricocheted off rocks. Hit nothing. The forest swallowed the sound, absorbed it like water into sand.

Then silence. Terrible silence.

Müller turned, his breath coming in gasps. Only three men left, including himself. Wendelin and a soldier named Kohl.

“Where did they go? Where are they?” Wendelin’s voice shook, his rifle trembling in his hands.

“I don’t know. I didn’t see anything. I was looking right at Schmidt, and he just vanished.”

Kohl was praying quietly in German, his eyes closed. Müller wanted to scream at him to shut up, to stay alert, but he couldn’t find his voice.

Müller backed toward the ravine entrance, his weapon sweeping back and forth. “Move! Now! Get out of here!”

They ran, abandoning formation, abandoning tactics, abandoning everything except the primal need to escape. But the forest had changed. The path they’d taken in, the clear trail through the ravine was gone, overgrown, blocked by fallen logs and thick brush that Müller would have sworn wasn’t there 20 minutes ago. This wasn’t possible. They’d walked this way. He remembered every step. Now it was like the forest had rearranged itself, closed the door behind them, trapped them in a maze that shifted and changed.

Wendelin whispered, his voice barely audible. “What’s happening? This isn’t real. This can’t be real.”

Müller didn’t answer. He didn’t have an answer. He’d fought for three years. Seen men die in every way imaginable. But this… this was something else. This was fighting an enemy that didn’t follow rules, that didn’t exist in the normal world of bullets and blood and tactics. This was fighting the land itself.

Joseph moved through the trees like water flowing downhill, silent and fluid and inevitable. He’d taken three men without a sound. Pressure points learned from his grandfather. Sleeper holds that cut blood flow to the brain in seconds. Dragged them into the brush, bound and gagged with strips of cloth, hidden so completely that you could walk within feet and never see them.

Thomas had taken two more using different methods. Distraction, misdirection, appearing in one place to draw attention while striking from another. The others had scattered in panic, firing at shadows, wasting ammunition on empty forest.

Now only three remained. Müller, Wendelin, and Kohl.

Joseph watched them from above, perched in a tree with branches that shouldn’t have supported his weight, but did. They were lost. Disoriented, exactly as planned. He could take them now, all three. But that wasn’t the point. The point was the lesson. The point was making them understand. He signaled Thomas with a gesture so subtle that even Cartwright, watching through binoculars, missed it.

Let them run. Let them exhaust themselves. Let them understand what it means to be hunted.

Müller ran. Branches tore at his uniform, his face, his hands. His breath came in ragged gasps that burned his lungs. Wendelin and Kohl followed, crashing through the underbrush like wounded animals. They no longer cared about noise or discipline or anything except survival. The forest was a blur. Trees that all looked the same, paths that led nowhere. The sun was up there somewhere, but the canopy was so thick that direction meant nothing.

Then Kohl tripped, fell hard over a root that seemed to reach up and grab his boot. His ankle twisted with an audible crack. He screamed.

Müller stopped, turned back. Every instinct screamed at him to keep running, to save himself, but he was still a soldier, still an officer. He grabbed Kohl’s arm.

“Get up. We’re not leaving you.”

Kohl looked up at him, eyes wide with pain and terror. “I can’t. My ankle. It’s broken. I can’t walk.”

Müller hesitated. He could hear it now. Something moving in the brush. Not loud. Not obvious. Just a whisper of movement. A sense of presence. He looked up into the trees. Saw nothing, just shadows, just leaves. But he knew, knew with absolute certainty that they were surrounded, that whatever had taken his men was right there, invisible and patient, waiting for the perfect moment.

He let go of Kohl’s arm. The soldier’s eyes widened.

“No, please don’t leave me. Please.”

Müller backed away. “I’m sorry. I’m so sorry.”

He ran. Wendelin followed without hesitation, his face white with terror.

Kohl screamed after them, his voice raw and desperate. “Don’t leave me! Come back! Please God, come back!”

The scream cut off abruptly. Not a fade, not a gradual silence. Just there and then not there. Like someone had flipped a switch. Müller didn’t look back. Couldn’t look back. He just ran, tears streaming down his face, knowing he’d just condemned a man to death, but unable to stop himself.

By midday, Hoffman’s group returned to the rendezvous point, a distinctive rock formation that was supposed to be easy to find. Müller wasn’t there. Hoffman waited, his patience wearing thin. 1 hour, 2 hours, no sign, no radio contact, nothing. The radios produced only static, like something was interfering with the signal. He sent two men to backtrack Müller’s route, to find out what had happened.

They returned an hour later, pale, shaking. One of them, a veteran named Braun, who’d survived the Eastern Front without flinching, could barely speak. His hands trembled as he tried to light a cigarette.

“They’re gone. All of them.”

Hoffman grabbed Braun’s collar, pulling him close. “What do you mean gone? Explain.”

Braun stammered, his eyes unfocused. “We found the ravine. We found tracks, bootprints, signs of struggle, but no bodies, no blood, just… equipment. Helmets scattered on the ground. Rifles leaning against trees like they’d been carefully placed there. Backpacks opened and contents spread out like they just decided to leave everything and walk away. But there’s no trail out, no tracks leading anywhere. They’re just… gone. Vanished.”

Hoffman released him, his mind racing. This was wrong. All wrong. He’d seen ambushes, seen massacres, seen the aftermath of partisan attacks where bodies were left as warnings. But this, this was something else entirely. No bodies meant prisoners or desertion. But six men don’t desert simultaneously. And if they were prisoners, there would be signs, drag marks, blood, something.

He looked at his remaining men. Five left. Out of 12, half his patrol gone in less than 6 hours without a single confirmed enemy sighting.

“We’re pulling back now. Forget the mission. Forget intelligence gathering. We’re getting out of this forest.”

One of his men, a young soldier named Fischer, spoke up. “Sir, what about Müller? What about the others?”

Hoffman’s voice was hard. “They’re gone. We can’t help them. We can only save ourselves. Move out. Now.”

They moved fast. No longer following trails or gathering intelligence. Just heading east, back toward German lines, back towards safety, back toward something that made sense. Hoffman kept his men tight in a defensive formation that would make any ambush costly. No one separated. No one lagged. But the forest seemed to stretch impossibly. Every mile felt like 10. The trees looked the same. The paths looped back on themselves in ways that defied logic. Hoffman checked his compass repeatedly. It spun lazily, the needle refusing to settle on any direction. Useless, broken, or something else.

One of his men whispered, his voice tight with barely controlled panic. “Sir, we’ve passed this tree before. I’m sure of it.”

Hoffman looked. A distinctive split trunk. Lightning struck at some point, the scar obvious. The man was right. They’d passed it 30 minutes ago. They were walking in circles. Impossible. He’d been navigating by the sun, by terrain features, by every skill learned in 3 years of war. But somehow they were lost. Completely and utterly lost in a forest that shouldn’t have been big enough to get lost in.

Hoffman forced himself to stay calm, to think clearly despite the fear clawing at his mind.

“We navigate by landmarks. Find a stream. Streams flow downhill. Downhill leads to valleys. Valleys have roads. We find a stream and follow it.”

They searched, found nothing. The forest was dry despite rain two days ago. No streams, no water, just endless trees and undergrowth and silence.

Fischer spoke again, his voice cracking. “Sir, this doesn’t make sense. There should be water here. There are streams on the map.”

Hoffman didn’t answer. The map meant nothing now. They were in a place where maps didn’t work. Where compasses spun uselessly, where the normal rules of navigation and terrain had been suspended.

Night fell like a hammer. One moment there was dim light filtering through the canopy. The next, complete darkness. Hoffman ordered his men to dig in, to create a defensive position. No fire, no light, just silence and darkness and waiting. They sat in a rough circle, weapons pointing outward, each man responsible for a sector.

Hoffman stayed awake, his eyes straining against the darkness, his ears picking up every sound. The forest was alive now, rustling in the bushes, snapping branches, footsteps that came close, but never close enough to see. Voices that might have been wind, but sounded like whispers. One man started crying quietly, trying to muffle it. Hoffman didn’t stop him. Didn’t even acknowledge it. What could he say? That everything would be fine. That they’d make it out. He didn’t believe it himself.

By dawn, two more men were gone. Fischer and Braun. Just gone. Hoffman had been awake all night, watching, listening. His eyes had never closed. He hadn’t dozed, hadn’t looked away. But when the sun rose, when the dim light finally penetrated the canopy, two men who’d been sitting 5 ft away were simply not there anymore. Their weapons were there. Their equipment was there. But the men were gone.

Wendelin stared at the empty spots. His face blank with shock. “How? I was looking at them. I saw them. They were right there.”

Hoffman had no answer. No explanation that made sense. No tactical analysis that fit. This wasn’t combat. This was something else. Something older. Something that didn’t care about tactics or training or experience.

Three men left. Himself, Wendelin, and a soldier named Keller, who hadn’t spoken in hours. Hoffman made a decision. The only decision left.

“We surrender.”

Wendelin looked at him like he’d spoken a foreign language. “Sir, what?”

Hoffman stood, his legs shaking with exhaustion and fear. “We can’t fight what we can’t see. We can’t escape what we can’t understand. We surrender. Maybe they’ll take us prisoner. Maybe we’ll survive. It’s the only chance we have.”

He raised his hands above his head, called out in English, his accent thick but understandable. “We surrender! We are unarmed! We want to be prisoners!”

No response. Just the forest. Just the sound of wind through leaves that might have been laughter. Hoffman called again, louder, desperation creeping into his voice. “We surrender! Show yourselves! We will not resist!”

Silence.

Then from behind him, so close he could feel breath on his neck. A voice quiet, calm, utterly without emotion.

“Lower your weapons. Place them on the ground. Step back 10 paces. Do it now.”

Hoffman turned slowly. Saw nothing. Just trees, just shadows. The voice came again from a different direction.

“Do it now or join your men.”

Hoffman nodded to Wendelin and Keller. They lowered their rifles with trembling hands, placed them on the ground like they were made of glass. Stepped back slowly, hands raised.

A figure emerged from the shadows 20 ft away. Joseph. Then Thomas from another direction. Then Cartwright and Roscoe from behind. Four men. Four Americans.

Hoffman stared. Four men had destroyed his entire patrol. 12 veteran Wehrmacht soldiers gone, captured, defeated, without a single shot fired.

Joseph stepped forward, his face expressionless. “Your men are alive. Captured, bound, and hidden. They’ll be collected and sent to POW camps. You walked into our land. You thought you owned it. You thought your training and your experience made you superior. You were wrong. This land doesn’t care about your tactics. It doesn’t care about your weapons. It only cares about who understands it, who respects it, who becomes part of it. You remained separate. You remained invaders, and the land treated you accordingly.”

Hoffman said nothing. He just stared at the Apache scout who moved like a ghost, who saw trails in bare dirt, who hunted without sound or sight, who had defeated an entire patrol using nothing but knowledge passed down through generations.

Joseph turned to Cartwright. “Take them back. Secure them. Make sure they’re treated well. They surrendered. They deserve respect for that.”

Cartwright nodded, pulling out zip ties. He and Roscoe secured the prisoners efficiently. As they prepared to move out, Wendelin looked back at Joseph, his young face marked by tears and exhaustion.

“How did you do it? How did you make us disappear? Make the forest itself fight us?”

Joseph met his eyes, and for a moment something passed between them. Understanding maybe, or recognition that they were both just soldiers following orders, caught in a war neither had chosen.

“You were taught to fight the land, to dominate it, control it, bend it to your will. We were taught to become it, to join it, to move with it instead of against it. Your way works when the land is empty. Our way works when the land is alive. This forest has been alive for thousands of years. It knows us. We know it. You were strangers. And strangers don’t survive here.”

Back at the American camp, Captain Harrison listened to Cartwright’s report with growing amazement. 12 Germans, 11 captured, one still missing, probably captured as well. No American casualties, no shots fired, no combat in any traditional sense.

Harrison looked at Joseph and Thomas, who stood quietly to the side. “You did exactly what I thought you’d do. Exactly what your people have been doing for centuries.”

Joseph said nothing, his face neutral. Thomas smiled slightly.

Harrison continued. “The Army’s going to want a full debrief. This changes how we operate in forest terrain. This changes doctrine. We’ve been fighting the land. You’ve shown us how to fight with it.”

Cartwright lit a cigarette. His hands steady now. The shaking had stopped. The doubt had stopped. He looked at Joseph with something close to reverence. “I owe you an apology. I thought you were a waste of resources. I thought command had lost their mind sending you here. I was wrong.”

Joseph shook his head slightly. “You thought what you were taught to think. What your training told you was true. Now you know different. Now you know there are other ways to fight. Older ways. Ways that don’t require bullets or bombs. Just patience, knowledge, and respect for the land itself.”

Cartwright nodded slowly. “Yeah. Now I know different. And I’ll never forget it.”

Word spread fast through the American lines. The story of the Apache Scout and the Vanish Patrol became legend within days. Other units requested Native American scouts. Officers who’d been skeptical suddenly wanted to know more. The Army began formal training programs, integrating traditional tracking methods with modern tactics. Native American soldiers who’d been relegated to support roles suddenly found themselves in demand. Joseph and Thomas trained dozens of scouts over the following months. Taught them to read the land, to move without sound, to see what others missed.

The German intelligence reports noted the change, warned their units about American scouts who could appear and disappear, who could track patrols through impossible terrain, who seemed to know where German soldiers would be before they got there. But warnings didn’t help. You can’t fight what you can’t see. You can’t track what leaves no trail. You can’t defeat knowledge passed down through generations, refined over centuries, adapted to survival itself in the harshest conditions imaginable.

The Germans had laughed at the scouts when they first heard about them, called them primitive, mocked their methods, made jokes about savages and reservations. But in the Hürtgen Forest, in the mountains of Italy, in the hedgerows of France, in every place where the land was thick and complex and alive, those scouts proved something the textbooks never taught.

War isn’t just about firepower or numbers or technological superiority. It’s about knowing the land, understanding it, becoming it. And when you face someone who’s been doing that for thousands of years, whose ancestors survived by reading tracks and moving silently and understanding that the land itself is alive, all your tanks and all your training and all your modern doctrine won’t save you. You’ll just disappear. Like Hoffman’s patrol, like Müller’s men, like so many others, gone without a shot, swallowed by a forest that chose its side long before the war began, that remembered when these lands belonged to people who understood that survival meant partnership with nature, not domination of it.

Joseph and Thomas stayed with the unit through the end of the war. They participated in dozens of operations, saved countless American lives by finding German positions, by tracking enemy movements, by teaching others to see what they saw. When the war ended in May 1945, they returned home. No medals, no parades, no recognition beyond a few lines in unit reports that most people would never read. Just the quiet satisfaction of knowing they’d done what their ancestors had always done: protected their people, defended their land, used knowledge that others had dismissed as primitive to win battles that others thought required modern technology, and proved that some skills never become obsolete, no matter how advanced warfare becomes.

Cartwright kept in touch with Joseph for years after the war. They exchanged letters regularly, shared stories, became friends in a way that would have seemed impossible that first day when Cartwright had dismissed the scouts as useless.

In one letter written in 1952, Cartwright asked the question that had haunted him since that day in the Hürtgen Forest. How did you make 12 armed, trained veteran soldiers disappear without firing a shot? How did you turn an entire forest into a weapon?

Joseph’s response came 3 weeks later. The handwriting was careful, precise.

We didn’t make them disappear. We didn’t turn the forest into a weapon. We just let the forest do what it does naturally. Swallow those who don’t belong. Confuse those who don’t understand. Exhaust those who fight instead of flow. We just showed it where to look. Showed it who the invaders were. The forest did the rest. It always does. People think the land is neutral, dead, just terrain to be crossed or controlled. But the land is alive. It remembers. It chooses. And if you know how to ask, how to listen, how to become part of it instead of separate from it, the land will fight for you. That’s not magic. That’s not mysticism. That’s just truth that most people have forgotten.

Decades later, historians would study the role of Native American soldiers in World War II. Code talkers received recognition finally, after years of classified silence. Their contribution to communication security was acknowledged, celebrated, turned into books and movies. Scouts received footnotes, brief mentions, a paragraph here and there in specialized texts. But those who were there, who saw what men like Joseph and Thomas could do, never forgot.

Roscoe told the story to his grandchildren every Thanksgiving, his hands gesturing wildly as he described men who could vanish into thin air, who could read stories in dirt, who could move through forests like they were part of the trees themselves. His grandchildren thought he was exaggerating, making it more dramatic. They didn’t understand that he was actually downplaying it, that the reality had been even more impossible, even more incredible than his story suggested.

Cartwright wrote about it in his memoir published in 1967, a chapter called The Ghosts of Hürtgen. Most readers assumed it was metaphorical, poetic license, a way of describing the horror of forest combat. Only other veterans who’d been there understood he was being literal, that he was describing exactly what happened, that 12 German soldiers really had vanished in less than a day, captured by four men who used methods that seemed impossible to those trained in modern warfare.

Even Wendelin, the German soldier who survived, spoke about it in interviews years later. He’d moved to America after the war, started a new life, tried to forget, but he never forgot that day in the forest. He described the terror of being hunted by something invisible. The helplessness of watching his comrades vanish one by one. The absolute certainty that he was going to die in that forest. That he’d never see home again. And the grudging respect he felt when he finally saw his captors. Four men against 12. And it wasn’t even close. The forest had chosen. And the forest never loses.

The lessons learned from Joseph and Thomas and the other Native American scouts influenced American military doctrine for decades. Special forces training incorporated tracking techniques derived from traditional knowledge. Survival schools taught methods of moving silently, of reading terrain, of becoming part of the environment. Modern soldiers learned skills that had been dismissed as primitive just years before.

But something was lost, too. The deep connection to land, the generational knowledge, the understanding that the earth itself is alive and aware. Those things couldn’t be taught in a manual, couldn’t be learned in a classroom. They required a lifetime, generations. A culture built on survival through partnership with nature rather than domination of it.

Joseph understood this. In his last letter to Cartwright written just before Joseph’s death in 1978, he wrote about the future, about what would be lost and what might be preserved. He wrote that the scouts had proven something important, that old knowledge has value, that technology doesn’t replace wisdom, that the fastest way forward sometimes requires looking back. He hoped people would remember, would understand, would preserve the knowledge that had saved so many lives. But he wasn’t optimistic. The world was changing, moving faster, forgetting more. Still, he’d done his part, fought his war, proved his worth. That was enough.

If you enjoyed this story of how ancestral knowledge became the ultimate weapon, how patience and understanding defeated firepower and training, how four men using methods thousands of years old defeated 12 soldiers armed with the best equipment 1944 could provide… Subscribe to the channel for more untold stories from World War II. Hit the like button and leave a comment telling us which historical event you’d like to see covered next. History isn’t just about the battles everyone knows, the famous generals, the big invasions. It’s about the moments that changed everything, fought by people whose names we’ve forgotten, but whose legacy lives on in every lesson learned, every life saved, every impossible victory won through knowledge that others dismissed as worthless.

The story of Joseph Nicha and Thomas Big, and all the other Native American scouts who served in World War II, deserves to be remembered, deserves to be told, deserves to be understood not as a footnote, but as a fundamental truth about warfare, about survival, about the value of knowledge that spans generations. Remember their names. Remember what they did. Remember that sometimes the oldest ways are still the best ways, and that the land itself, if you know how to listen, will always tell you the truth.

News

Antique Shop Sold a “Life-Size Doll” for $2 Million — Buyer’s Appraisal Uncovered the Horror

March 2020. A wealthy collector pays $2 million for what he believes is a rare Victorian doll. Lifesize, perfectly preserved,…

Her Cabin Had No Firewood — Until Neighbors Found Her Underground Shed Keeping Logs Dry All Winter

Clara Novak was 21 years old when her stepfather Joseph told her she had 3 weeks to disappear. It was…

My Wife Went To The Bank Every Tuesday for 20 Years…. When I Followed Her and Found Out Why, I Froze

Eduardo Patterson was 48 years old and until 3 months ago, he thought he knew everything about his wife of…

Her Father Lockd Her in a Basement for 24 Years — Until a Neighbor’s Renovation Exposed the Truth

Detroit, 1987. An 18-year-old high school senior with a promising future, vanished without a trace. Her father, a respected man…

“Choose Any Daughter You Want,” the Greedy Father Said — He Took the Obese Girl’s Hand and…

“Choose any daughter you want,” the greedy father said. He took the obese girl’s hand. Martha Dunn stood in the…

Her Son Was Falsely Accused While His Accuser Got $1.5 Million

He was a 17-year-old basketball prodigy. College scouts line the gym. NBA dreams within reach. But one girl’s lie shattered…

End of content

No more pages to load