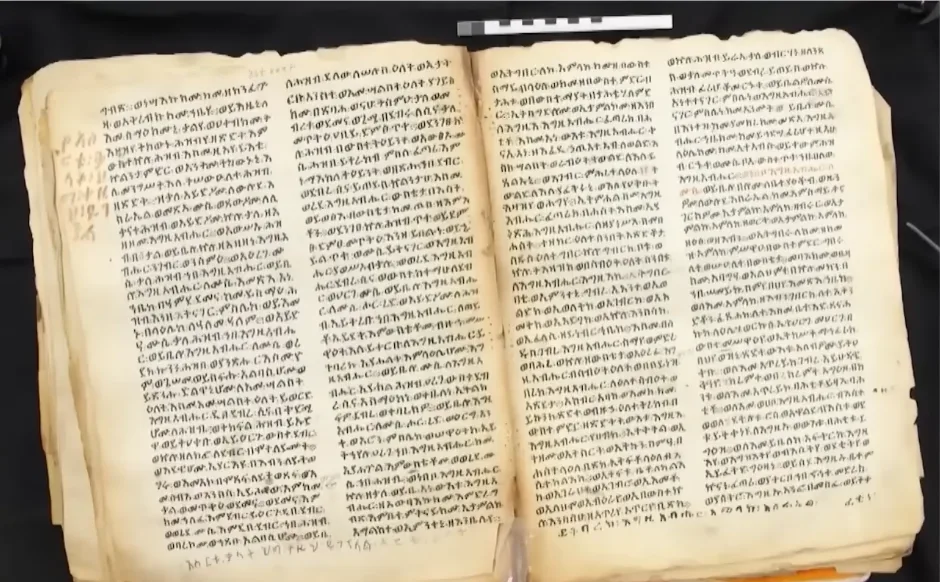

This is a rare Ethiopian Orthodox Bible manuscript, handwritten in Ethiopia’s sacred liturgical language. And if there’s one thing you should understand from the beginning, it’s this: everything you think you know about the resurrection may be missing pieces.

For nearly 2,000 years, the world has been told the same ending.

The tomb is empty.

The stone is rolled away.

Silence follows.

Credits roll.

But that ending was never universal.

Thousands of miles away from Rome, deep within the stone monasteries of Ethiopia, monks preserved a different record—an ancient biblical tradition untouched by Western councils and theological edits. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church safeguarded a Bible with 81 books, not 66. Pages the West never read. Words never preached. Teachings never systematized.

And hidden within those pages is a resurrection account that doesn’t merely describe what happened after Jesus rose from the dead—it explains what fundamentally changed. Not just death. Not just heaven. But the nature of God, the structure of reality, the purpose of the human soul, and humanity’s direct access to truth.

These texts survived beyond empires, beyond censorship, beyond institutional control. And now, after centuries of isolation, they are resurfacing.

The Bible That Was Never “Finished”

Most people assume the Bible is fixed, final, and untouchable. But the Ethiopian Orthodox Church never agreed.

While Protestant Bibles contain 66 books and Catholic Bibles 73, Ethiopia preserved 81—15 more than Protestants and eight more than Catholics. These aren’t random additions. Many of them are among the oldest Christian texts ever used, revered by early believers long before they were excluded from Western canon.

Books like Enoch, Jubilees, and Maccabees were treated in the West as myth or legend for centuries. Then science intervened. Radiocarbon dating of the Garima Gospels—discovered in an Ethiopian monastery—confirmed they were written between 330 and 650 AD, making them the oldest illustrated Christian manuscripts known.

While Europe fell into chaos, Ethiopian monks were quietly preserving what some now call Christianity’s original source code.

Enoch, the Watchers, and Forbidden Knowledge

The Book of Enoch doesn’t simply claim humanity sinned before the flood. It explains why.

According to Enoch, 200 watcher angels descended to Earth, took human wives, and produced hybrid beings known as the Nephilim—giants who consumed the world. These beings weren’t just violent; they introduced forbidden knowledge: weapon-making, astrology, enchantment, seduction.

This wasn’t disobedience alone. It was unauthorized knowledge.

Enoch names names—Samyaza, Azazel, Barakiel—and describes a world spiraling into chaos. That chaos, critics argue, is exactly why the Roman Church rejected the text. It presents a universe that is unstable, dangerous, and uncontrollable.

Ethiopia kept it.

And Enoch, according to Ethiopian tradition, is only the beginning.

The Forty Days the West Never Taught

The most controversial text is known as Mashafä Qeddus, often called The Book of the Covenant.

In Western tradition, the resurrected Jesus appears briefly before ascending. In Ethiopian tradition, He remains forty days—and He teaches. Not sermons, but instructions. Not parables, but explanations.

He speaks about hidden structures of reality. About knowledge that bypasses religious hierarchy. About nature, frequencies, spirits, and an end-times conflict not fought with armies, but with awareness.

According to Ethiopian belief, the 81-book canon represents the narrow gate, while the 66-book Bible is the wide path—simplified for the masses.

If that’s true, then the Bible most of the world reads isn’t complete. It’s filtered.

A Warning About Religion Itself

In these forty days, Jesus doesn’t comfort—He prepares.

He warns of a deceptive force governing material systems: money, power, empires. He tells His followers not to build temples of stone, but temples of the heart. He predicts religious leaders who will wear robes, hoard wealth, and weaponize His name. He warns explicitly of a future Rome that will turn the cross into a sword.

The specificity unsettles scholars.

He describes humanity as carrying two winds: the wind of life and the wind of error. The latter is portrayed like a parasite, entering through greed, corrupt speech, and distorted desire. Once inside, it calcifies the heart, turning a person into what He calls a walking tomb—alive physically, dead spiritually.

The antidote is not ritual or tithe. It is gnosis—knowledge. Awareness. Mastery of thought. Recognition that the kingdom of heaven is not external, but internal, hidden in the silence between thoughts.

A self-aware believer, these texts suggest, is uncontrollable.

Science, Symbolism, and Strange Accuracy

The Book of the Covenant also describes cosmological structures once dismissed as poetic: storehouses of snow, gates of wind, and an abyss of water beneath the Earth.

Modern science now confirms global atmospheric rivers and a vast subterranean ocean locked within Earth’s mantle. These parallels raise uncomfortable questions. If the text was right about winds and water, what else might it be right about?

“The Darkness Will Wear My Face”

Perhaps the most chilling line attributed to the resurrected Christ in these texts is this:

“The darkness will come, and it will wear my face.”

The warning isn’t of an obvious monster, but of deception cloaked in holiness. Evil appearing as Christianity itself. A savior that destroys by imitation.

This reframes traditional ideas of the Antichrist—not as an outsider, but as something embedded within trusted institutions.

Ethiopia, the Ark, and a Different Center of Authority

Ethiopia doesn’t just claim unique texts. It claims the Ark of the Covenant.

According to Ethiopian tradition, the Ark rests in the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion in Axum, guarded by a single monk forbidden to leave for life. Accounts describe guardians suffering physical deterioration, fueling speculation that the Ark is more than symbolic—perhaps technological.

Ethiopia is also the only African nation never colonized. Its Solomonic dynasty ruled nearly 3,000 years, claiming direct descent from King Solomon through Menelik I, the son of the Queen of Sheba.

If true, biblical authority may not point to Rome—but to Africa.

Rock-Hewn Churches and Impossible Engineering

In Lalibela, eleven massive churches were carved directly downward into solid volcanic rock in the 12th century. Not built. Excavated.

Modern engineers argue the project should have taken centuries. Local tradition says humans worked by day and angels by night, using tools of light.

Even today, laser scans reveal hidden chambers beneath the structures—sealed for 800 years.

Bloodlines, Not Just Beliefs

In the West, Jesus stands alone. In Ethiopian tradition, lineage matters.

Genetic studies confirm ancient Levantine DNA within Ethiopian populations, supporting migration from Jerusalem around 3,000 years ago. Ethiopian Christianity retained Jewish practices—dietary laws, circumcision, Sabbath observance—suggesting continuity, not conversion.

Some traditions go further, suggesting Jesus may not have died on the cross and that Ethiopia would have been the safest refuge—a land ruled by His extended family.

Why Now?

For centuries, these manuscripts were hidden in mountain monasteries, wrapped in goatskin, protected by men who would die before surrendering them.

Now they’re everywhere.

Unauthorized translations. Online discussions. Algorithms pushing them into the mainstream.

Some Ethiopian interpretations claim these texts were never meant to surface until humanity entered an age of illusion—a world where people speak without mouths and see without eyes.

A hyperconnected, artificial reality.

Sound familiar?

According to the most radical readings, these texts are an emergency release—a fail-safe meant to awaken humanity when institutions collapse and meaning evaporates.

The question isn’t whether these claims are comfortable.

The question is whether we’re ready to read what was never meant to be hidden forever.

As Ethiopian monks say:

“The West has the water.

We have the well.”

News

🎰 Host HUMILIATED Ali on Live TV—What Ali Said Next Left Him Crying and Apologizing

In 1974, on live television in front of nearly 40 million viewers, a famous American broadcaster looked at Muhammad Ali…

🎰 The Tragic Fate Of BJ Penn: When Talent Isn’t Enough

“When I look back,” BJ Penn once said quietly, “it’s going to be like… man, I really did that.” But…

🎰 Marvelous Marvin Hagler: The Champion Who Made War a Discipline

Before the bell ever rang, Marvin Hagler had already won. Not with trash talk.Not with theatrics.But with certainty. When asked…

🎰 When John Wayne Tried to Break Muhammad Ali—and Ended Up Broken Himself

In 1971, John Wayne was still the most powerful man in Hollywood. He wasn’t just a movie star. He was…

🎰 The Sad Truth About Chuck Liddell’s Brain Damage, At 55 Years Old…

He was the face of an era. A shaved mohawk like a war flag.Fists of iron.A stare that promised violence….

🎰 Rich Franklin: The Teacher Who Redefined What a Fighter Could Be

What happened to Rich Franklin? For newer fans, his name might not come up as often as it should….

End of content

No more pages to load