The Ethiopian Church did something no other Christian tradition dared to do. Instead of carefully filtering religious literature, it preserved everything—texts that others debated, rejected, or tried to erase. While much of the Christian world narrowed its canon, Ethiopian monks chose inclusion over discretion. And that single decision may have preserved an entirely different version of Christian history.

Recently, a once-forbidden manuscript page was released by Ethiopian monks—despite centuries-old orders demanding its destruction. The page explicitly mentions Jesus, and its contents are forcing scholars to reconsider what they thought they knew about the origins of Christianity. The question now is unavoidable: why was this text silenced, and who benefited from keeping it hidden?

Christianity Before the Roman Empire

What many people don’t realize is that Christianity did not originate as a Roman religion. Long before it became the faith of emperors and councils, it was already deeply rooted in Africa.

Ethiopia is widely regarded as the first Christian kingdom in the world. In the early fourth century—during the 320s and 330s—King Ezana of Axum (often rendered as King Aana in oral tradition) declared Christianity the official religion of the kingdom. That happened more than fifty years before Rome made Christianity its state religion in 380.

This detail alone reshapes the timeline. While Roman leaders were still arguing over doctrine, councils, and authority, Ethiopia was already living out the faith as a national identity. Christianity there did not grow under imperial pressure or political strategy. It grew organically.

This is not a footnote in history. It is one of the most important facts in the entire Christian story.

A Civilization That Didn’t Need Rome

Ethiopia was not a fragile culture borrowing ideas from Europe. It was a wealthy, independent kingdom with its own currency, international trade routes, and intellectual life. It had scholars, artists, and theologians centuries before Europe entered the Middle Ages.

This independence mattered. Because Ethiopia was never ruled by Rome or later European empires, it never had to submit to outside religious control. Its churches used their own language, Geʽez, their own artistic symbols, and their own theological priorities.

And most importantly, they kept their books.

While wars, fires, and political purges destroyed libraries across Europe and the Near East, Ethiopian monks retreated into the mountains and copied manuscripts by hand—again and again. For them, these writings were worth more than gold, more than power, even more than life itself.

Proof Written in Gold

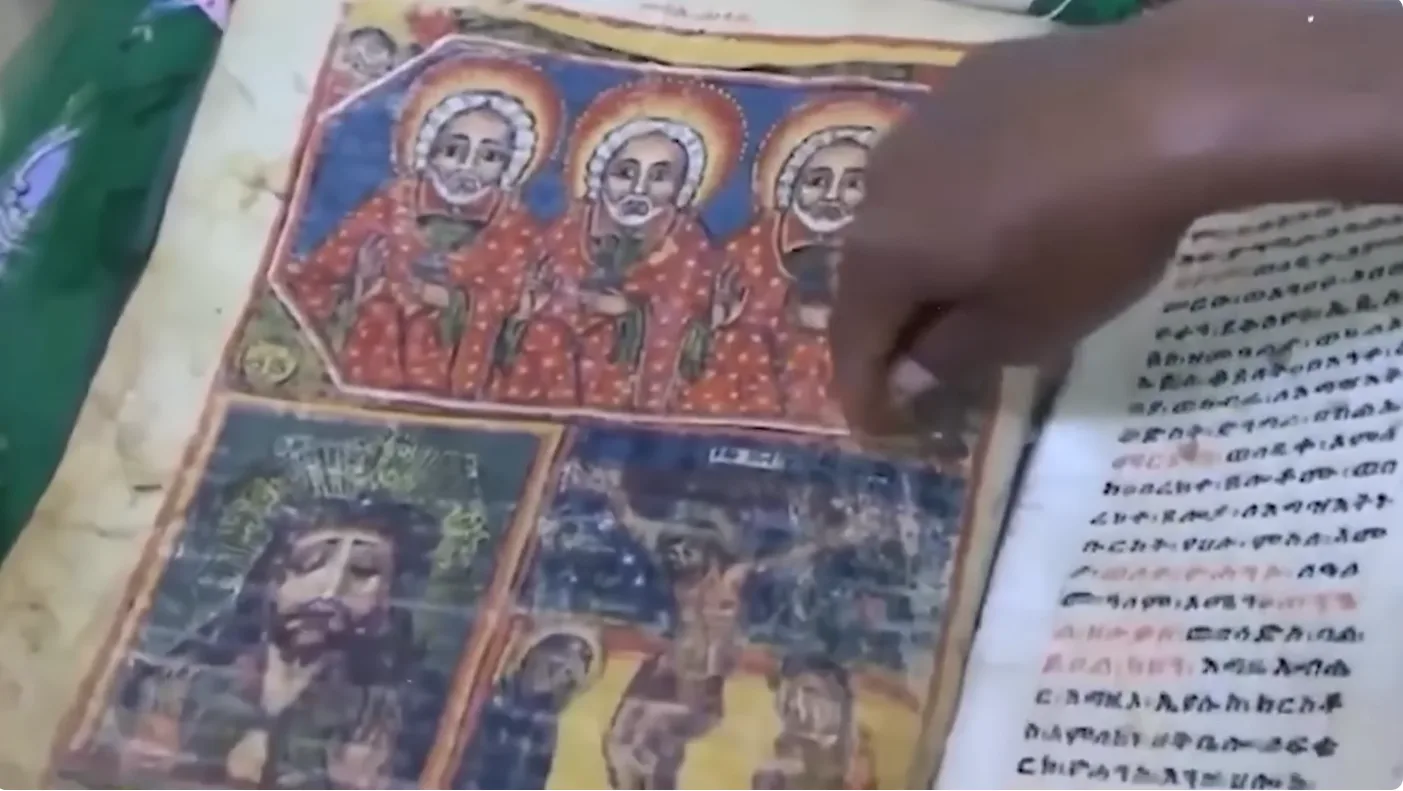

The physical evidence still exists.

The Garima Gospels—ancient Ethiopian manuscripts written in gold ink on parchment—have been studied by scholars from institutions like Oxford University. Radiocarbon dating places some of these texts as early as the late fourth century, around the year 390.

These are not crude or derivative works. They are masterpieces of theology, art, and craftsmanship, produced by a culture that fully understood the message of Jesus without needing European interpretation.

This is why modern scholars are stunned. Ethiopia did not merely preserve Christianity—it preserved an early form of it, one that developed outside Roman political influence.

The Books the World Lost—and Ethiopia Didn’t

Ethiopia is the only place on Earth that preserved complete versions of two ancient and controversial texts:

the Book of Enoch and the Book of Jubilees.

Everywhere else, these books survive only in fragments—scraps in Greek, Hebrew, or Aramaic. Scholars in the West spent centuries searching caves and libraries for missing pieces, trying to reconstruct what the original texts might have said.

All that time, Ethiopian monks were reading the complete versions as part of daily worship.

The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls confirmed that these books were not fringe writings. They were central to early Jewish and Christian thought. So why were they removed from Western Bibles?

The uncomfortable answer many historians now admit is control.

Western church leaders favored texts that supported institutional authority and clear hierarchy. They were wary of books filled with visions, angels, cosmic mysteries, and divine encounters that bypassed church leadership. Ethiopia had no such concern. Isolated in the mountains and free from imperial pressure, it chose spiritual depth over administrative simplicity.

The Book of the Covenant and the Forty Days After Resurrection

Among Ethiopia’s most significant texts is one almost unknown outside the tradition: Mashafa Kidan, commonly called The Book of the Covenant.

According to Ethiopian belief, this book records what Jesus taught His closest followers during the forty days between His resurrection and ascension. In Western Christianity, this period is barely described. In Ethiopian Christianity, it is the heart of spiritual instruction.

The teachings in this book are not about church structure or religious law. They focus on inner transformation, deep prayer, spiritual awareness, and direct connection with God. For over a thousand years, Ethiopian monks have used these teachings to train priests and holy men.

The number forty is deeply symbolic in biblical history—Moses on the mountain, Israel in the wilderness—and the idea that these final teachings were preserved intact makes this text especially significant.

This is not a “new discovery.” The monks have had it all along. What is new is that the rest of the world is finally reading it.

Two Paths, One Faith

As history moved forward, Christianity split into two distinct paths.

One path ran through Rome, where faith became intertwined with empire, unity, and political order. Councils debated doctrine, and lists of acceptable books were gradually finalized—not at Nicaea, as commonly believed, but over centuries of institutional refinement.

The other path ran through Axum.

Ethiopia was not interested in managing an empire. It was interested in preserving the soul of the faith. It kept books that Rome rejected, not by accident, but by choice. Those texts spoke to mystery, vision, and transformation rather than governance.

That decision shaped the entire identity of the Ethiopian Church—and preserved a spiritual worldview the rest of the world lost.

Why This Matters Now

Today, many people feel disillusioned with institutional religion. They are searching for something older, deeper, and more personal. In that search, eyes are turning toward Ethiopia.

The manuscripts, mountain libraries, and ancient traditions are not relics of the past. They are a map—evidence that Christianity once existed without empire, without censorship, and without fear of mystery.

Ethiopia did not just save books for itself. It saved them for the future.

And now the question becomes unavoidable:

Have we been reading a shortened version of history for nearly 2,000 years?

If the earliest Christians had access to these texts from the beginning, how differently might faith—and the world—have developed?

The forgotten kingdom may not have been forgotten at all. It may have simply been waiting.

News

🎰 Host HUMILIATED Ali on Live TV—What Ali Said Next Left Him Crying and Apologizing

In 1974, on live television in front of nearly 40 million viewers, a famous American broadcaster looked at Muhammad Ali…

🎰 The Tragic Fate Of BJ Penn: When Talent Isn’t Enough

“When I look back,” BJ Penn once said quietly, “it’s going to be like… man, I really did that.” But…

🎰 Marvelous Marvin Hagler: The Champion Who Made War a Discipline

Before the bell ever rang, Marvin Hagler had already won. Not with trash talk.Not with theatrics.But with certainty. When asked…

🎰 When John Wayne Tried to Break Muhammad Ali—and Ended Up Broken Himself

In 1971, John Wayne was still the most powerful man in Hollywood. He wasn’t just a movie star. He was…

🎰 The Sad Truth About Chuck Liddell’s Brain Damage, At 55 Years Old…

He was the face of an era. A shaved mohawk like a war flag.Fists of iron.A stare that promised violence….

🎰 Rich Franklin: The Teacher Who Redefined What a Fighter Could Be

What happened to Rich Franklin? For newer fans, his name might not come up as often as it should….

End of content

No more pages to load