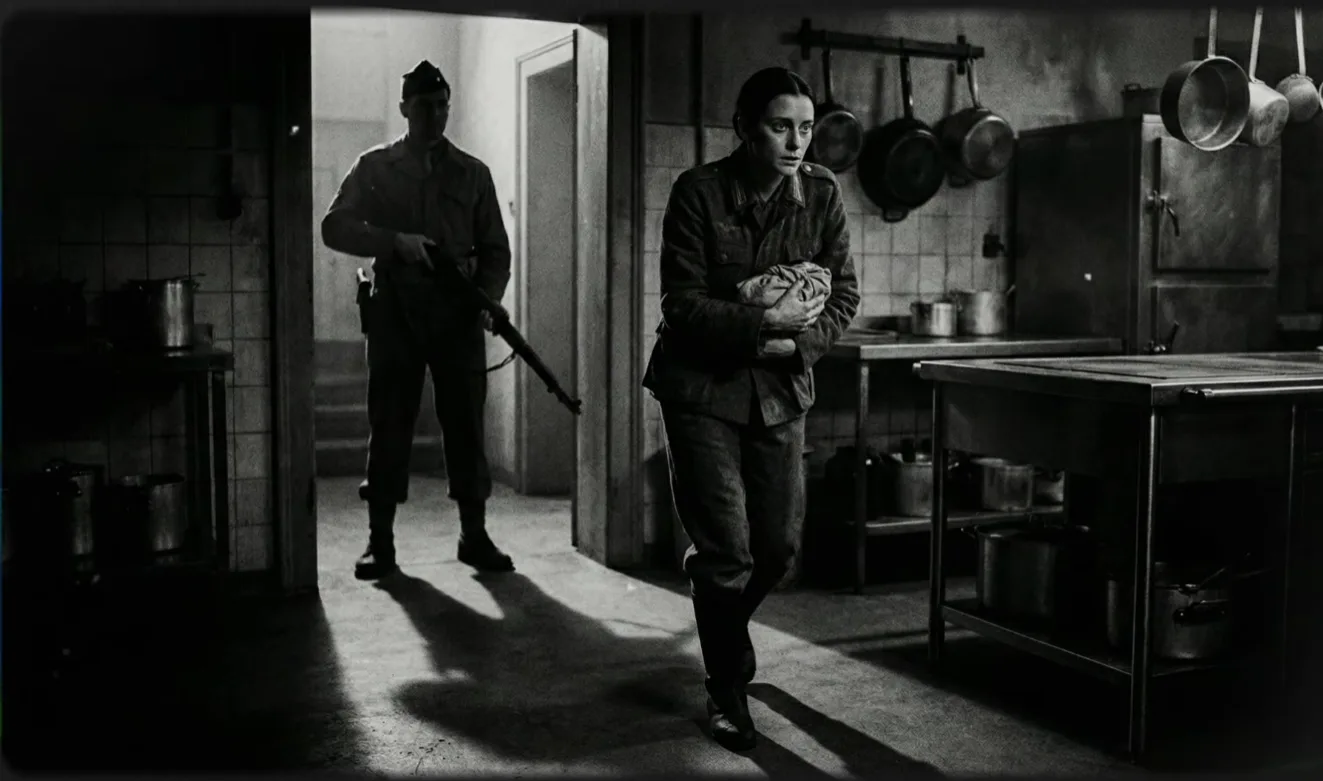

The bread was still warm when Margaret Vogle slipped it under her shirt.

Her hands shook as she pressed the stolen loaf against her ribs, feeling the heat through the thin fabric of her prison uniform.

The camp kitchen was empty.

The American cooks had left for their shift change.

She had maybe 90 seconds before someone returned.

60 seconds.

She moved toward the door, forcing herself to walk normally.

Not too fast.

Prisoners who ran always got caught.

30 seconds.

Her fingers touched the door handle.

Almost there.

Almost.

“Stop right where you are.”

The voice came from behind her.

American accent.

Deep.

Calm.

Margaret froze.

She’d been caught.

The training from Ravensbrook clicked into her mind automatically.

Deny everything.

Show no fear.

never apologized to the enemy.

She turned slowly.

An American soldier stood in the kitchen doorway, Sergeant Stripes on his sleeve, maybe 35, weathered face, eyes that had seen too much war.

His rifle was slung over his shoulder, not raised, not threatening, just there.

He looked at her, at her hands pressed against her ribs, at the shape of the bread clearly visible under her shirt.

“You know, stealings against camp regulations,” he said.

Margaret said nothing.

Her German military training had been clear.

Admit nothing, even when caught.

The sergeant tilted his head slightly.

“You speak English?”

“Yes.”

“Then you understand what I’m saying. You stole food from the camp kitchen. That’s a disciplinary offense.”

She waited for what came next.

The beating, the solitary confinement, the reduction in rations that would leave her even hungrier than before.

Instead, Sergeant William Hayes did something that would haunt Margaret Vogle for the next 60 years.

He reached into his pocket, pulled out a pencil and a small notepad, and wrote something down.

Then he tore off the page and held it out to her.

“This is a requisition slip,” he said.

“For two loaves of bread, one jar of jam, and a canteen of milk authorized by me. Take it to the supply office tomorrow morning.”

Margaret stared at the paper, at his hand holding it out to her, at his face, which showed no anger, no mockery, no trap.

“I don’t understand,” she whispered.

“The bread you stole,” Hayes said quietly.

“It’s not enough to share with whoever you’re stealing for, so I’m giving you more.”

Margarette didn’t take the paper.

She couldn’t.

Her hands wouldn’t move.

because nothing in her training, six years in the German women’s auxiliary, two years as a signals operator, eight months as a prisoner of war, nothing had prepared her for an enemy who responded to theft with generosity.

“Why?” The word came out broken.

Hayes looked at her for a long moment.

Then he set the requisition slip on the counter between them.

“Because you’re hungry enough to risk solitary confinement for a loaf of bread,” he said.

“And because I remember what hungry looks like.”

He turned to leave, then paused at the door.

“Next time you need food, just ask. We’re not in the business of starving prisoners.”

The door closed behind him.

Margaret stood alone in the kitchen, the stolen bread still pressed against her ribs, the requisition slip sitting on the counter like evidence of something she couldn’t comprehend.

The Americans were supposed to be brutal.

That’s what every officer in the Vermach had told them.

That’s what the propaganda broadcasts had promised.

Capture meant torture, starvation, death.

But this American soldier had just caught her stealing and given her more food instead of punishment.

And that act of inexplicable mercy was about to destroy everything Margaret Vogle believed about the war, about the enemy, and about which side had truly been fighting for civilization.

Before we continue Margaret’s story, I need to tell you something.

Every week I dig through archives, interview historians, and piece together these forgotten moments when someone’s entire world view shattered.

And every week, someone tells me these stories don’t matter, that nobody cares about what happened to German prisoners, that I should focus on real victims.

But I believe these moments when enemies became human to each other, when propaganda met reality, when someone chose mercy over revenge, these are the stories that show us who we really are.

So please stay tuned to the end with all the love in your heart and subscribe to untold captive stories.

Help me prove that complicated truth matters more than comfortable lies.

Now, let’s return to that kitchen in Louisiana, 1945, where a German woman held a piece of paper that made no sense and a loaf of bread that would change everything.

Margaret Vogle had been hungry before.

Not like this, not the grinding, constant hunger that turned your stomach into a knife and made you think about food every waking moment.

But she’d known rationing.

She’d known scarcity.

She’d grown up in Stoutgart, daughter of a postal worker and a seamstress, smart enough to finish gymnasium, not wealthy enough for university.

When the war started in 1939, she was 22, working as a telephone operator for the Reich Postal Service.

By 1941, they’d asked for volunteers, women to support the war effort.

Not as soldiers.

German women didn’t fight but as auxiliaries, radio operators, signal clerks, administrative staff, the Nrrican Helerinan, communication helpers.

Margaret had volunteered, not out of ideology, not out of patriotism, out of practicality.

The auxiliary paid better than the postal service.

It offered better rations, and it got her out of Stuttgart before the bombing got worse.

They stationed her in France, then Poland, then back to Germany as the Allies closed in.

She was good at her job.

Morse code, signal routing, radio protocols.

She could decode intercepted messages faster than most of the men.

By 1944, she’d been promoted to senior signals operator, working out of a mobile command post that moved with retreating German forces.

March 1945, the Americans crossed the Rine.

Margaret’s unit had been ordered to evacuate east to burn all classified documents to destroy radio equipment before retreat.

But orders came too late, or confusion was too great, or both.

The Americans overran their position outside Mannheim on a gray morning that smelled like diesel and smoke.

Margaret hadn’t even had time to finish destroying the code books when American soldiers appeared in the doorway, rifles raised, shouting in English she barely understood, “Hands up! Move slow. You’re prisoners of war.”

They’d processed her through a forward camp, cataloged her rank, her unit, her role, then put her on a truck with 40 other German women, nurses, clerks, radio operators, all captured in the final chaotic weeks.

The ship to America took 12 days.

Margaret spent most of it in the cargo hold, sick from the motion, terrified of what awaited.

The propaganda had been clear.

Americans were savage.

They’d torture German prisoners, especially women, especially those who’d served in military intelligence.

But when the ship docked in New Orleans, what greeted them wasn’t torture.

It was heat.

Impossible wet, suffocating Louisiana heat that pressed down like a physical weight.

hand American soldiers who processed them with board efficiency, who handed them prison uniforms and towels and bars of soap, who spoke in draws she could barely understand, but whose meaning was unmistakable.

Follow the rules.

Work your assigned duties.

Cause no trouble.

That was 6 weeks ago.

Now Margaret stood in Camp Concordia, a converted army training facility in northern Louisiana, surrounded by barbed wire and guard towers and American soldiers who didn’t act like the monsters she’d been warned about, and she’d just been caught stealing bread.

Margaret took the stolen bread back to her barracks after midnight.

The women’s compound was a separate section of Camp Concordia.

Wooden buildings arranged in neat rows housing 200 German female prisoners, nurses, clerks, radio operators, a few luftvafa auxiliaries who’d manned search lights and anti-aircraft predictors.

She shared barracks 7 with 15 other women.

Most were asleep when she slipped through the door, but Hilda Schmidt was awake, sitting on her bunk, writing a letter home by moonlight through the window.

Hilda looked up as Margareta entered, saw the bread, said nothing.

Margaret moved to her own bunk and carefully divided the loaf into 16 pieces.

Small pieces, barely enough to taste, but enough to share.

She set aside one piece and carried the rest through the barracks, placing them silently on each sleeping woman’s pillow.

When she returned to her bunk, Hilda was watching her.

“You were gone a long time,” Hilda said quietly.

“I was careful.”

“Did anyone see you?”

Margaret hesitated, then nodded.

Hilda’s face went pale.

Who?

An American sergeant.

Margaret?

No.

What did he do?

Margaret pulled the requisition slip from her pocket and handed it to Hilda.

Hilda read it by moonlight.

Read it again.

Then looked at Margaret like she’d lost her mind.

This is a trick,

Hilda whispered.

They’re testing you.

Tomorrow they’ll arrest you when you try to use it.

Maybe.

Why would an American give you more food for stealing?

I don’t know.

What did he say to you?

Margaret sat on her bunk, feeling the weight of exhaustion.

He said, “Next time I should just ask.”

Hilda stared at her.

“Ask?”

That’s what he said.

“The Americans are our enemies, Margaret. They don’t give prisoners food for asking.”

Then why did he give me this?

Neither of them had an answer.

Margarett saw Sergeant William Hayes again 3 days later.

She’d avoided the kitchen since the night she was caught.

Avoided him.

Avoided the supply office where the requisition slip sat unused in her pocket like evidence of something she couldn’t explain.

But avoiding was impossible in a camp of 200 prisoners and 50 guards.

Paths crossed, duties overlapped.

She was hanging laundry on the line behind barracks 7 when Hayes walked past on patrol.

He slowed when he saw her, stopped.

“You didn’t use the requisition slip,” he said.

“Margaret’s hands stilled on the wet sheet she was hanging.”

“No.”

“Why not?”

She didn’t answer.

Hayes came closer, not threatening, just close enough to speak without shouting.

“You think it’s a trap, isn’t it?”

“No, ma’am.

Then why give it to me?”

Hayes was quiet for a moment.

Then he said, “Can I ask you something?”

Margaret nodded.

“Who are you stealing for? Yourself or someone else?”

The question was too direct, too observant.

Margaret felt something crack in her carefully maintained walls.

“The older women in my barracks,” she said quietly.

“They’re rationed the same as us, but they can’t eat the camp food. It’s too rich, too much salt. They need plain bread.”

Hayes nodded slowly.

And you’re feeding them from your own rations.

It’s not enough.

That’s why you stole.

Yes.

Hayes reached into his pocket and pulled out a new requisition slip.

This one authorized plain white bread twice weekly for medical dietary needs.

Take this to the camp infirmary,

he said.

Tell them you need medical ration authorization for barracks 7.

They’ll set it up.

Margaret took the paper with trembling hands.

Why are you doing this?

Because you’re taking care of people who can’t take care of themselves,

Hayes said.

That’s not criminal.

That’s decent.

He started to walk away.

Sergeant.

He turned.

We’re enemies.

Margaret said.

You’re supposed to.

She didn’t know how to finish.

Hayes smiled, but it was sad.

“Yeah, we’re supposed to hate each other. Supposed to be monsters to each other. But I’ve got a mother back in Kansas who’s probably hungry right now, too. And if she was in a camp somewhere, I’d hope somebody would look after her.”

He walked away.

Margaret stood holding the requisition slip, feeling the Louisiana sun press down, feeling something shift in her understanding of the world.

Over the next month, Margaret encountered Sergeant William Hayes seven more times.

She was working kitchen duty, scrubbing pots after the evening meal.

Hayes came through during his rounds, checking the work details.

He paused when he saw her hands raw, bleeding slightly from the harsh soap and steel wool.

The next day, softer soap appeared in the kitchen.

Gloves, too.

No one said where they came from, but Margaret knew.

A fight broke out in the women’s compound.

Two prisoners, both half starved, both desperate, arguing over a missing piece of bread.

Hayes was the guard who responded.

He separated them calmly, sat them down, asked what happened.

When they explained, he reached into his own ration bag and gave them each a piece of chocolate.

“Now you’re even,” he said.

“And now you both have something sweet.”

“Problem solved.”

Margaret watched from the barracks doorway, unable to reconcile this man with the enemy she’d been taught to fear.

Sunday recreation time.

The women were allowed outside for 2 hours.

Some played cards, some read, some just sat in the sun.

Margaret was sitting alone when Hayes walked past.

He paused.

You play chess?

She looked up, surprised.

Yes.

Good at it.

I used to be.

Hayes pulled a folded chessboard from his pack, a travel set, pieces stored inside.

“I need practice,” he said.

“Nobody here plays worth a damn. You interested?”

For the next four Sundays, they played chess.

Hayes won twice.

Margaret won twice.

They drew three times.

They didn’t talk much during the games, just moved pieces, exchanged pawns, built strategies in silence.

But after the fourth game, Hayes said something that changed everything.

“You’re good at seeing patterns,” he said.

“Better than me. You think three moves ahead.”

“That was my job,” Margaret said.

“Signals, intelligence, pattern recognition.”

Hayes nodded.

Must have been hard watching the war fall apart through intercepted messages.

Yes,

you knew Germany was losing before most people did.

It wasn’t a question, but Margaret answered anyway.

We knew by 1943, but we couldn’t say it.

Defeatism was treason.

So, you kept working.

What else could we do?

Hayes looked at her.

You could have run

where?

We were soldiers.

We had orders.

You were women forced to choose between orders and survival.

The distinction hit Margaret like a blow.

She’d never thought of it that way.

She’d enlisted.

She’d volunteered.

She’d been part of the machine.

But Hayes was right.

By the end, it wasn’t service.

It was survival.

The trouble started when Oberloitant Friedrich Bower noticed.

Bower was a German officer captured near Cologne transferred to Camp Concordia in late April.

He’d been Luftwafa, a career officer, mid-40s, rigid with the kind of discipline that came from 20 years in uniform.

The male and female compounds were separate, but they shared the messaul, the infirmary, the recreation yard.

Bower saw Margaret and Hayes playing chess, saw them ah talking, saw the way Hayes treated her with respect, with something approaching friendship, and Bower didn’t like it.

He approached Margaret after Sunday recreation when she was walking back to her barracks.

“Fran Vogle,” he said formally.

She stopped, turned.

Old habits kicked in.

When an officer addressed you, you stood at attention.

Oberloitant.

I’ve noticed you’ve become friendly with one of the American guards.

It wasn’t a question.

It was an accusation.

Sergeant Hayes is professional,

Margaret said carefully.

He plays chess with you.

That’s more than professional.

He plays chess with several prisoners,

but he talks to you differently.

I’ve watched.

Margaret felt something cold settle in her stomach.

What are you suggesting?

Bower stepped closer, his voice dropped.

I’m suggesting that fratonization with the enemy is a betrayal of Germany.

That you’re being used.

That when this war ends and we return home, there will be a reckoning for those who collaborated.

I’m not collaborating.

You’re playing chess with an American soldier while German civilians starve in the rubble.

You’re smiling.

You’re comfortable.

You’ve forgotten which side you’re on.

I haven’t forgotten anything,

Margaret said, anger rising.

I remember that we lost.

I remember that the Reich collapsed because it was built on lies.

And I remember that these Americans could starve us or beat us or execute us.

and instead they feed us and house us and treat us like human beings.

Bower’s face went hard.

You’ve been broken.

I’ve been shown the truth.

The truth is that you’re a traitor.

The word hung between them like poison.

I saved women from starving.

Margarete said quietly.

I shared bread.

I followed camp rules.

I did nothing wrong.

You befriended an enemy soldier.

That’s collaboration.

And when we return to Germany, I’ll make sure everyone knows what you did here.

Bower walked away.

Margaret stood alone, shaking.

Margarett avoided Hayes for two weeks after Bower’s threat.

No more chess games.

No more conversations.

She kept her head down, worked her shifts, stayed silent.

Hayes noticed.

On the third Sunday, he approached her during recreation time.

“You’re avoiding me,” he said.

“Yes,

why?”

Margarett looked at him at this American soldier who’d shown her more kindness than her own officers, who’d treated her like a human being instead of an enemy.

“Because you’re making my life harder,” she said.

Hayes frowned.

“How?”

“The other prisoners think I’m collaborating. They think I’m a traitor because I talk to you.

You’re not a traitor for having a conversation.

That’s not how they see it.

Hayes was quiet for a moment.

Then he said, “What do you see it as?”

The question cut through everything.

Margaret had been asking herself that same question for weeks.

What was she doing?

What did these conversations mean?

I see it,

she said slowly,

as the first time in six years that someone treated me like a person instead of a tool.

Hayes nodded.

That’s not collaboration.

That’s being human.

But when we go home, when we’re sent back to Germany, they’ll say I was too friendly with Americans.

They’ll say I forgot my loyalty.

Did you?

I don’t know anymore,

Margaret whispered.

I don’t know what loyalty means when the country I served doesn’t exist anymore.

When the officers who gave orders are being tried for war crimes?

When the propaganda I believed turned out to be lies.

Hayes pulled the chessboard from his pack, set it on the bench between them.

You want to know what I think?

He said yes.

I think you’re punishing yourself for surviving, for being treated well while your country suffers, for finding out that the enemy wasn’t what you were told.

He started setting up the chess pieces.

But here’s the thing, Margaret.

You didn’t start this war.

You didn’t choose the regime.

You were a woman doing a job in a system that would have punished you for refusing.

And now you’re a prisoner being offered basic human decency.

That’s not betrayal.

That’s just what should have been normal all along.

Margaret sat down across from him.

The others will hate me,

she said.

Probably.

They’ll say I collaborated.

Let them.

Why should I?

Hayes looked at her across the chessboard.

Because you’re smarter than them.

Because you figured out that the propaganda was lies.

And because refusing to be human just to avoid judgment is letting fear win.

He moved his first pawn.

Your move.

Margaret looked at the board at the pieces arranged in their starting positions at the choice in front of her.

She moved her pawn forward.

In June 1945, the mail system finally worked consistently.

The Red Cross had established channels.

Letters could flow between Germany and America, though heavily censored, though delayed by weeks or months.

Margaret received her first letter from home on a Tuesday morning.

It was from her sister, Claraara, still in Stogart, living in what remained of their parents’ apartment building.

The letter was three pages long.

Claraara wrote about starvation, about the black market, about American occupation forces, about the trials beginning in Nuremberg.

But the last paragraph stopped Margarett’s heart.

We heard from Frabau that you’ve been seen fratonizing with American soldiers in the prison camp, that you play games with them, that you smile and laugh while we starve.

I don’t want to believe it, Margaret.

Please tell me it’s not true.

Please tell me you haven’t forgotten who you are.

Margaret sat on her bunk, hands shaking.

Bower had written home, had told his wife, who had told Margaret’s sister the poison was already spreading.

She could write back, could deny it, could say Bower was lying, that she’d been a model prisoner, that she’d never spoken to an American except when required.

She could save her reputation or she could tell the truth.

That night, Margarete wrote two letters.

Letter one to her sister.

Dear Claraara,

what Fra Bower told you is true.

I have spoken with American soldiers.

I have played chess with a sergeant named William Hayes.

I have smiled.

I will not apologize for this.

The Americans who guard us here have fed us, housed us, and treated us according to the rules of war.

They could have starved us.

They could have beaten us.

Instead, they gave us dignity.

I know Germany is suffering.

I know you’re hungry.

And I carry that guilt every day.

But punishing myself by refusing kindness doesn’t feed you.

It just makes me cruel.

The war is over, Claraara.

The regime is gone and we have to decide what kind of people we’ll be in, whatever comes next.

I’m choosing to be honest.

I’m choosing to recognize humanity, even in former enemies.

If that makes me a traitor in your eyes, I understand.

But I won’t lie to protect a loyalty to a regime that destroyed our country.

With love,

Margaret

left her too to Sergeant Hayes.

She found him on evening patrol, handed him a folded piece of paper.

“What’s this?” Hayes asked.

“A thank you,” Margarette said.

“For treating me like a human being, for showing me that enemies can choose to be decent to each other.”

Hayes unfolded the paper.

It was a sketch.

Margaret had drawn it from memory, the chessboard from their last game, the position where she’d finally beaten him after he’d won three straight.

At the bottom, she’d written in careful English.

You taught me that winning isn’t about destroying your opponent.

It’s about respecting them enough to play your best game.

Thank you for playing with honor.

MV.

Hayes looked at the drawing for a long time.

Then he folded it carefully and put it in his pocket.

You’re going home soon,

he said.

Repatriation starting in July.

I know

it’s going to be hard.

I know that, too.

The people there won’t understand what happened here.

They’ll judge you for surviving well.

Margaret smiled sadly.

They already are.

Hayes was quiet.

Then he said, “Can I tell you something my father told me before I shipped out?”

Yes.

He said, “The war will end, son. And when it does, you’ll have to decide what kind of man you were during it, not what kind of soldier.”

“What kind of man?”

“I think that applies to you, too. What kind of person was I?” Margaret asked.

“Someone who stole bread to feed the hungry. Someone who chose truth over comfort. Someone who refused to stop being human just because the world went insane.

He held out his hand.

It’s been an honor knowing you, Margaret.

She shook his hand, felt the firmness of his grip, the respect in the gesture.

The honor was mine, Sergeant.

Margaret Vogle returned to Germany in August 1945.

The ship docked in Bremen.

The city was rubble.

70% destroyed, refugees everywhere, hunger everywhere.

She made her way to Stuttgart by train and by foot.

Her sister Claraara met her at what remained of their building.

The embrace was stiff, uncertain.

You look healthy,

Claraara said.

It sounded like an accusation.

I was fed,

Margarete replied.

We weren’t.

I know.

They stood in the ruins of their childhood home.

And Margarette understood that some gaps couldn’t be bridged.

Some judgments couldn’t be changed.

But she didn’t lie.

She didn’t pretend.

She didn’t apologize for surviving.

40 years later, in 1985, Margarete received a letter from America.

It was from William Hayes, now retired, living in Kansas with his wife and two grown daughters.

Dear Margaret,

I hope this letter finds you well.

I’ve thought about you often over the years, wondered what became of the German woman who taught me that even in war, people can choose to be decent to each other.

I’m writing because my daughter is studying history at university.

She’s writing about German PWs in America.

I told her about you, about the bread you stole to feed others, about the choice you made to be honest instead of safe.

She asked me what I learned from the war.

I told her I learned that the enemy is only a monster if you choose to see them that way.

That sometimes the bravest thing you can do is refuse to hate.

Thank you for teaching me that.

Thank you for the chess games.

Thank you for choosing truth.

Your friend

William Hayes

Margaret kept that letter for the rest of her life.

She kept it in a frame on her wall next to a sketch she’d drawn in 1945, a chess board with pieces midame.

When people asked about it, she told them the truth.

This, she would say, is from the war, not from the fighting.

from the moment after when I stole bread and was caught by an enemy soldier who gave me more instead of punishment.

Why did he do that?

They would ask.

And Margaret would smile.

Because he understood something the war tried to make us forget.

That we’re all human first and enemies second.

And that sometimes if we’re very lucky, we get the chance to prove it.

News

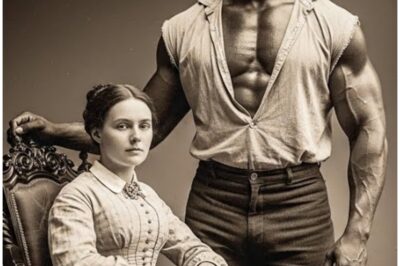

🎰 She Was Deemed Unmarriageable—So Her Father Gave Her to the Strongest Slave

The Story of Elellanar Whitmore and Josiah Freeman Virginia, 1856 They said I would never marry. Twelve men in four…

🎰 Beaten Daily by Her Mother… Until a Quiet Mountain Man Took Her Away to a Life She Never Expected

They say blood is thicker than water, but for 18-year-old Sarah, her own mother’s blood was filled with nothing but…

🎰 3 Doves at the Feet of Our Lady of Fatima and the miracle happened?

Imagine a silent procession full of faith, where the heart of an entire nation beat in unison. And in the…

🎰 Ethiopia’s Forgotten Scriptures and the Christianity That Came Before Rome

The Ethiopian Church did something no other Christian tradition dared to do. Instead of carefully filtering religious literature, it preserved…

🎰 Bridge collapses in India during procession and miracle of Our Lady of Guadalupe happens live

In a small community in a remote region of India, where local customs and traditions blended with the seed of…

🎰 Shroud of Turin: The Religious Artifact That Cannot Be Explained

For years, critics claimed the Shroud was a medieval forgery, no more than a few hundred years old. That narrative…

End of content

No more pages to load