I had never met Aunt Marjorie, knew her only as a name whispered at holiday gatherings with the particular reverence reserved for those who had survived things others preferred to forget. When the executor called to say she had left me her personal effects, I assumed it was a mistake—some confusion of names or distant relations. But the will was clear: Everything to Eleanor Bishop, grand-niece, the one who asks too many questions.

It was the questions, I suppose, that had led me to open the Bible first, ignoring the boxes of china and the brass candlesticks wrapped in newspaper from 1987. I had always been told our family kept no photographs from before the war, that a fire had claimed them all, that the past was simply gone. Yet here, pressed between psalms and proverbs, was a portrait so formal and so strange that I sat with it for nearly an hour before I understood what I was seeing.

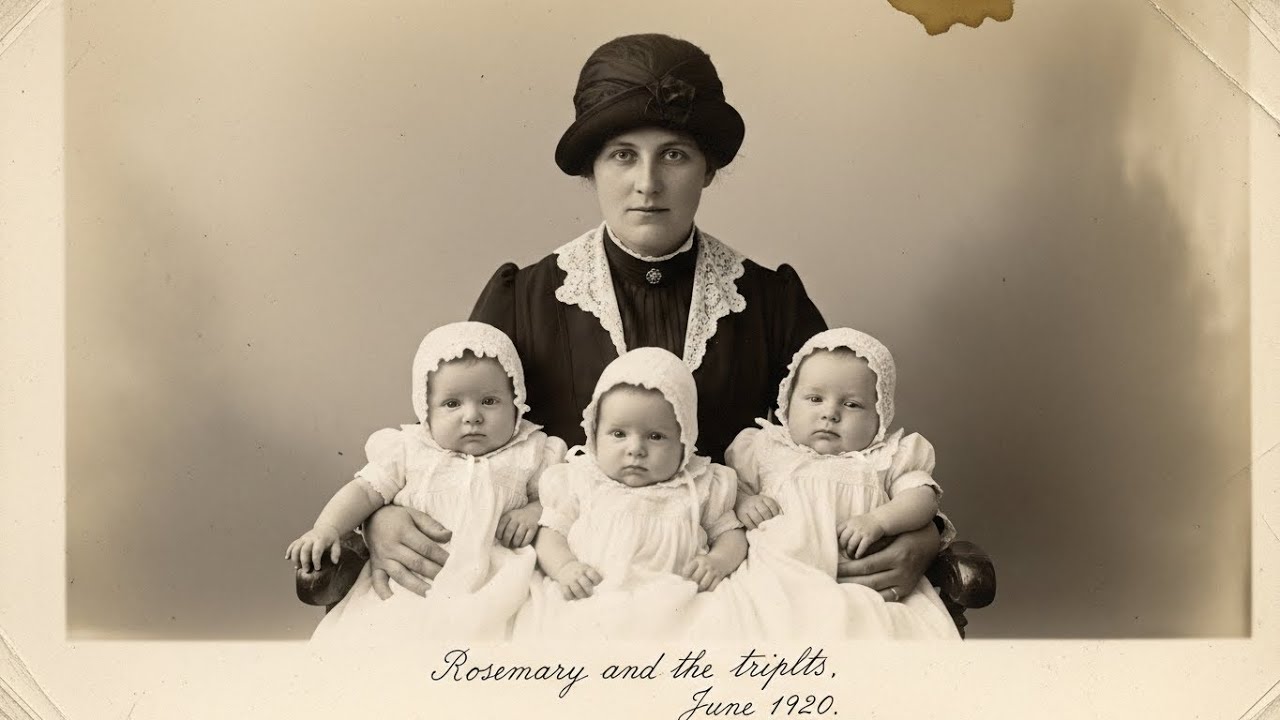

A woman in her early 30s stares directly at the camera, her dark hair pinned beneath a modest hat, her dress high-collared and severe in the fashion of another era. She is not beautiful in any conventional sense, but there is a quality to her face—a kind of fierce containment—that makes it impossible to look away. On her lap, arranged like dolls in a shop window, sit three infants in matching white christening gowns, their faces round and placid, their tiny hands folded or reaching toward the camera’s lens.

The photograph had been labeled in faded ink along the bottom edge: Rosemary and the triplets, June 1920. Below that, in a different hand, someone had added a single word: Survived.

I turned the image over, expecting perhaps a studio stamp or a date, but found instead a fragment of a letter, the paper yellowed and brittle, the handwriting cramped as though the author had been working by poor light or in great haste. The words were only partially legible:

…cannot say which was hers and which were not. But she loved them all the same, and that is what matters now. When so much else has been taken, they must never know. Promise me, Marjorie. Promise me they will never know.

The letter ended there, the rest of the page torn or rotted away, leaving me with a mystery that would consume the next six months of my life.

I had always believed that family secrets were the province of novels, that real people simply forgot or moved on, that the passage of decades eroded everything but the blandest facts. But as I began to research Rosemary Bishop, my great-great-grandmother, I discovered that some silences are not the result of forgetting, but of deliberate, painstaking concealment—and that the truth, when it finally emerges, can illuminate not only the past, but the present, revealing connections and debts we never knew we owed.

The first thing I learned was that Rosemary had never given birth to triplets.

Medical records from the county hospital, preserved in an archive that smelled of mold and old paper, showed that Rosemary Bishop had been admitted on the night of May 3rd, 1920, suffering from what the attending physician described as a “catastrophic hemorrhage following a stillbirth.” She was 29 years old. She had been married for 7 years to a man named Thomas Bishop, a traveling salesman who was, according to the hospital’s intake notes, “somewhere in Ohio at the time of her admission.” There was no mention of triplets, no mention of live births, no mention of anything that might explain the three infants in the photograph taken six weeks later.

The hospital records painted a grim picture of those first days. Rosemary had lost consciousness twice during the night, her blood soaking through sheet after sheet until the nurses stopped counting. The attending physician, a Dr. Harold Weston, had written in his notes that he did not expect her to survive until morning, and that he had sent word to the local minister to prepare for last rites.

But Rosemary did survive—through some combination of stubbornness and luck and the particular strength that women of that era cultivated out of necessity. She was discharged on May 10th, one week after her admission, with instructions to rest and avoid exertion and to accept that she would never bear children. The discharge summary included a single line that I read and reread until the words burned themselves into my memory: Patient informed of permanent damage to reproductive organs. Prognosis for future pregnancies: impossible.

I sat in that archive for a long time after reading those words, the fluorescent lights humming overhead, the smell of old paper thick in my throat. I thought about Rosemary leaving the hospital, walking out into the May sunshine with empty arms and an empty womb, returning to a house that had been prepared for a baby who would never come. I thought about Thomas, still somewhere in Ohio, selling his wares and writing letters home that spoke of the future they would build together when he returned. I thought about the seven years of marriage that had preceded that night—the seven years of trying and hoping and praying, the seven years of watching other women’s bellies swell while her own remained flat and silent. And I thought about the photograph taken six weeks later, showing a woman with three infants on her lap and a look in her eyes that I could only now recognize for what it was. Not pride. But defiance.

I spent weeks in that archive cross-referencing birth certificates and death records, census data and church registries, trying to understand how a woman who had lost her only pregnancy could appear in a portrait with three healthy children.

The answer, when it came, arrived not from official documents, but from the diary of a midwife named Clara Henning, whose papers had been donated to the local historical society by her granddaughter in 1994. Clara had been 63 years old in 1920, a widow who had been attending births in the county for nearly 40 years. Her diaries, which spanned from 1882 to 1923, were written in a cramped hand that became increasingly difficult to read as the years progressed, the letters shrinking and tilting as though she were trying to fit too many secrets onto too few pages.

But her entry for May 5th, 1920, was longer and more legible than most, as though she had known even then that someone would need to read it someday.

She described being called to a farmhouse on the outskirts of town, a place she identified only as “the Henley property,” where a young woman had gone into labor three weeks early. The girl’s name was not recorded, only her age—16—and the circumstances of her condition, which Clara referred to obliquely as “a shame and a sorrow that has been visited upon this family through no fault of their own.”

The birth had been difficult, the girl weak and frightened, her mother standing in the corner of the room with her hands pressed to her mouth as though physically preventing herself from speaking. But by dawn, Clara had delivered three infants—two boys and a girl—all small but breathing, all crying with the thin, reedy wails of babies who had arrived before they were ready.

The girl had held them once, Clara wrote, cradling all three against her chest while tears ran down her cheeks and soaked into the blankets. Then she had looked up at her mother, at the woman who had not spoken a word throughout the entire labor, and asked what would happen now.

What followed was a negotiation that Clara recorded in painful detail, her handwriting becoming more uneven as the account progressed, as though she was struggling to write and weep at the same time.

The girl’s family, the Henleys, were respectable farmers with a reputation to protect. A reputation that would be destroyed if the community learned that their unmarried daughter had given birth to three illegitimate children. The father—a young man from a neighboring town who had been sent away by his own family when the pregnancy was discovered—would never be permitted to return. The infants would be taken to an orphanage in the city, where they would likely be separated and raised by strangers, their origins erased, their mother’s name forgotten.

The girl had begged. Clara recorded her words, or something close to them:

“Please, mother. Please let me keep at least one. Please don’t take all of them. I will be good. I will do whatever you ask. Only please, don’t take all of them away from me.”

But Mrs. Henley had been immovable, her face as hard and cold as the stone walls of the farmhouse. The children would go, the girl would recover, life would continue as though nothing had happened. This was the way things were done. This was the price of respectability.

Clara had left the farmhouse that morning with a heaviness in her chest that she described as “the weight of all the women I have ever attended, all the babies I have ever delivered, all the secrets I have ever been asked to keep.” She had walked home through the spring fields, the wildflowers blooming in the ditches, the sky so blue and clear it seemed to mock the darkness of what she had witnessed.

And she had thought, as she walked, about Rosemary Bishop, who was lying in her bed a few miles away, her body healed but her heart shattered, her arms aching for a child who would never come.

Clara did not record what made her turn around, what impulse or inspiration led her to retrace her steps to the Henley farmhouse that afternoon. But the diary entry for May 6th described a second conversation, this one with Mrs. Henley alone, conducted in the parlor while the girl slept upstairs and the three infants lay in a makeshift cradle by the fire.

Clara had proposed an arrangement. She knew a woman, she said—a woman of good reputation and steady character who had just lost a child and could never have another. This woman had a husband who traveled for work and would not return for several weeks. This woman had the means and the desire to raise children, to love them, to give them the life they deserved. If Mrs. Henley would agree to let Clara take the infants to this woman rather than to the orphanage, Mrs. Henley’s reputation would be preserved. The children would have a home. And everyone involved could pretend that the events of the past few days had never happened.

Mrs. Henley had been silent for a long time, Clara wrote, her hands folded in her lap, her eyes fixed on some point in the middle distance. Then she had asked a single question.

“Would my daughter ever see them again?”

Clara had said no. And Mrs. Henley had agreed.

The next morning, May 7th, 1920, Clara Henning wrapped the three infants in a basket lined with clean linen, covered them with a blanket to protect them from the morning chill, and carried them across the fields to the Bishop house. She did not take the road, fearing that she might be seen, that someone might ask what she was carrying, that the secret would unravel before it had even begun. Instead, she walked through the woods and the meadows, following paths that only she knew, arriving at Rosemary’s back door just as the sun was rising over the hills.

The diary does not record the conversation that followed, only its outcome. Clara wrote simply: Agreed. The children are hers now. God forgive us all.

By the end of that day, Rosemary Bishop had three children. The girl at the farmhouse had been told they had died, that their small bodies had given out during the night, that they had been buried in unmarked graves in the churchyard. The family Bible, which I now held in my hands, had been altered to include three new names written in Rosemary’s careful script: William, James, and Elizabeth Bishop, born May 3rd, 1920—the same date as her stillbirth, as though the lie had been designed from the beginning to fit seamlessly into the truth.

When Thomas Bishop returned from Ohio three weeks later, he found his wife sitting on the porch with three infants in her arms, her face radiant with a joy he had never seen before. She told him that she had given birth while he was away, that the labor had been difficult but that she and the babies had survived, that she had not written to him because she had wanted it to be a surprise. Thomas, who had been married to Rosemary for seven years and had seen her through countless disappointments and heartbreaks, did not ask questions. He took the babies from her arms one by one, held them against his chest, and wept with a happiness that required no explanation.

The lie was almost perfect.

Almost.

I returned to the photograph with new eyes, searching for the detail that had prompted someone—Marjorie, perhaps, or someone before her—to add that cryptic note. For a long time, I could see nothing unusual—only the standard arrangement of a family portrait, the mother’s arms encircling the infants, their tiny fingers curled or splayed against the white cotton of their gowns.

But then, as the light shifted and I tilted the image toward the window, I saw it.

The infants’ hands did not match.

Two of the children—the boys—had the round, dimpled hands of well-fed babies, the kind that appear in advertisements and greeting cards: plump and pink and perfect. Their fingers were short and stubby, their wrists creased with rolls of healthy fat, their skin smooth and unmarked. But the third child, the girl on the left, had hands that were longer and thinner, the fingers almost spidery, the wrists showing the faint shadows of bones beneath the skin. Her nails, visible even in the grainy photograph, were longer than her brothers’. And there was something about the way she held her hands, palms upward and fingers slightly curled, that suggested a different body, a different inheritance, a different origin.

This was not merely a difference in size or development. It was a difference in kind. The unmistakable evidence that these three children had not come from the same body, had not shared the same womb, had not been born on the same night.

I spent days researching, trying to understand what I was seeing. I consulted medical textbooks from the era, photographs of other triplets, studies of infant development and hereditary characteristics. I learned that identical triplets, which are extremely rare, would be expected to have nearly indistinguishable features at birth, while fraternal triplets might show some variation but would still share certain family resemblances, certain commonalities of proportion and structure. I learned that the differences I was seeing in the photograph—the dramatic disparity between the girl’s hands and her brothers’—would be highly unusual in any set of triplets, fraternal or identical.

And then I found another photograph.

It was buried in a box of miscellaneous papers that the historical society had not yet cataloged, a box labeled simply *Henley Family, 1890-1930.* The photograph showed a young woman, perhaps 16 or 17, standing in front of a farmhouse with a grim expression on her face. She was dressed in a simple cotton dress, her hair pulled back from her face, her hands clasped in front of her. And those hands—even across the distance of a century—were unmistakably the same hands I had seen in the photograph of Rosemary’s triplets: long, thin fingers, prominent knuckles, wrists like bird bones.

The young woman was identified on the back of the photograph as Sarah Henley, spring 1919—one year before the triplets were born.

I had found Elizabeth’s biological mother.

The discovery opened a new chapter of my research, one that took me deeper into the history of the Henley family and the small community that had surrounded them. I learned that Sarah Henley had been the youngest of four children, the only daughter in a family of sons—cherished and protected, and utterly unprepared for the realities of the world beyond her father’s farm. I learned that she had been beautiful in a fragile, ethereal way, with pale skin and dark hair and those distinctive hands that she had inherited from her grandmother, a woman who had immigrated from Sweden as a child and who had been known throughout the county for her skill at needlework and lacemaking.

I learned that in the summer of 1919, Sarah had fallen in love. His name was Daniel Crawford, and he was the son of a minister from a neighboring town—a young man of 20 who had come to help with the harvest, and who had stayed through the autumn, finding reasons to linger, finding excuses to be near the Henley farm, finding ways to see Sarah when her parents were not watching.

The courtship had been conducted in secret—in stolen moments behind the barn, and whispered conversations through Sarah’s bedroom window, in letters that were hidden under loose floorboards and destroyed before they could be discovered.

By October, Sarah knew she was pregnant. Daniel had promised to marry her. He had promised to speak to her father, to make things right, to give the child his name. But when he went to his own father, the minister, to confess what had happened, he was met not with understanding, but with fury. The Crawfords were a family of reputation and standing, and they would not allow their son to ruin himself by marrying a farmer’s daughter who had been foolish enough to “get herself into trouble.” Daniel was sent away that same night, shipped off to relatives in California, forbidden to write or to make any attempt to contact Sarah again.

Sarah had waited for him all through the winter as her belly swelled beneath her loose dresses and her mother’s eyes grew hard with suspicion. She had waited, believing that he would come back, that he would keep his promise, that love would triumph over circumstance. But by February, when the pregnancy could no longer be hidden and the truth had to be told, she had stopped waiting. She had stopped believing in anything at all.

The Henleys had handled the situation with the brutal efficiency that was common in such cases. Sarah was confined to the house, kept away from visitors, forbidden to leave her room except to use the privy. The official story was that she had fallen ill, that she was suffering from a wasting disease, that she was not expected to recover. The neighbors had sent casseroles and condolences, the minister had come to pray over her, and all the while, Sarah had lain in her narrow bed, feeling the babies move inside her, knowing that she would never be allowed to keep them.

Clara Henning had been the only person outside the family who knew the truth, and she had been sworn to secrecy—bound by the codes of her profession and by the fear of what the Henleys might do if she broke their trust.

But Clara had also been a woman of conscience—a woman who had spent her life bringing children into the world and who could not bear to see these three sent to an orphanage, separated and forgotten, raised without love.

And so she had made her choice.

The diary entries for the weeks following the transfer were sparse, as though Clara could not bring herself to write about what she had done. But in June, after the photograph had been taken, she allowed herself a brief reflection:

Saw R. in town today with the children. They looked healthy and well cared for. She smiled at me as she passed—a smile that said everything and nothing. I believe I did the right thing. I must believe it, or I will not be able to live with myself.

Rosemary had raised the three children as her own, with a devotion that bordered on ferocity. Neighbors and relatives who came to visit in those early months were impressed by how quickly she had recovered from the birth, how energetically she managed the demands of three infants, how naturally she seemed to have adapted to motherhood after so many years of disappointment. If anyone noticed that the children did not resemble each other—that Elizabeth’s hands were different from her brothers’, that she had a way of tilting her head that neither William nor James shared—they did not speak of it. In a small community, some things were best left unexamined. Some lies were kinder than truth.

Thomas Bishop, for his part, seems to have accepted the situation without question. His letters from this period, which I found in a box of family correspondence that had somehow survived the “fire” that was supposed to have destroyed everything, are full of wonder and gratitude and an almost childlike delight in his unexpected family. He wrote to his brother in Michigan about the babies’ first smiles, their first words, their first steps. He wrote about teaching William to throw a ball and James to whistle and Elizabeth to dance. He wrote about Rosemary, his beloved Rosemary, who had finally gotten the family she had always wanted, who had been transformed by motherhood into something radiant and whole.

He never wrote about the hands that did not match.

But someone noticed. Someone always notices.

Marjorie, my aunt, had been Elizabeth’s closest friend—the confidant of her childhood and the keeper of her secrets. They had grown up together in the same small town, attended the same school, shared the same dreams of escape and adventure. And it was Marjorie, according to a letter I found tucked into the back of Clara Henning’s diary, who had first asked the question that Elizabeth had been afraid to ask herself.

The letter was dated 1952, written in Elizabeth’s hand, and it was addressed to Clara Henning, who by then was in her 90s and living in a nursing home in the city. Elizabeth wrote that Marjorie had shown her the photograph, had pointed out the hands, had asked if Elizabeth had ever wondered why she looked so different from her brothers. Elizabeth wrote that she had taken the photograph to her mother, had demanded an explanation, had finally asked the question she had been suppressing for 32 years.

Mother looked at me for a long time, Elizabeth wrote. She looked at me the way she used to look at me when I was a child and had done something wrong—something that required discipline and correction. But she did not punish me. She did not even speak. She simply took the photograph from my hands, pressed it to her chest, and began to cry. And in her crying, I heard everything she could not say: that she loved me, that I was hers, that nothing else mattered. I did not ask again. Some truths are too heavy to bear.

Elizabeth died in 1978 at the age of 58, from a cancer that had spread through her body before the doctors could find it. Her brothers had both died before her—William in France, and James in his sleep—and she had spent her last years as the sole surviving child of Rosemary and Thomas Bishop, the keeper of the family secrets, the one who knew but never told.

Marjorie had been with her at the end. Marjorie had held her hand as she slipped away, had promised to keep the photograph safe, had sworn to protect the truth until someone was ready to hear it. And Marjorie had kept that promise for another 45 years—through her own marriage and widowhood, through the slow accumulation of years that turns a young woman into an old one, through all the chances she had to speak and all the reasons she had to stay silent—until she died and left everything to me.

I do not know why Marjorie chose me. Perhaps it was because I was the one who asked questions, the one who never accepted the easy answers, the one who had always sensed that there was more to our family’s story than anyone was willing to tell. Perhaps it was because she knew I would not be satisfied with the photograph alone—that I would dig and search and demand the truth until I found it. Perhaps it was simply because I was the last one left—the end of a line that had begun with a lie and a basket of borrowed babies and a woman’s fierce determination to be a mother.

But I prefer to think that Marjorie chose me because she knew I would understand.

I understand now what it meant to be Rosemary Bishop in May of 1920. To lie in a hospital bed with an empty womb and a broken heart. To be told that you would never have children, that the thing you wanted most in the world was forever beyond your reach. I understand what it meant to see Clara Henning standing at your back door with a basket in her arms, to hear her explain what she was offering and what it would cost, to make a decision in an instant that would shape the rest of your life.

I understand what it meant to love children who were not yours—to look at them every day knowing that somewhere a girl was grieving for them, that their real mother was living a lie just as surely as you were. I understand what it meant to keep that secret, to protect it, to carry it like a stone in your heart for 42 years until the day you died.

And I understand what it meant to be Sarah Henley—16 years old and pregnant and abandoned, watching your children be carried away in a basket, being told that they had died, living the rest of your life with a grief that had no name and no acknowledgment.

I found her eventually, or rather, I found what became of her. Sarah Henley married in 1923, a man named Robert Paulson who had a farm in the next county and who knew nothing of her past. They had four children together—three boys and a girl—and by all accounts, they were happy, or at least content, living out their lives in the quiet rhythms of rural existence. Sarah died in 1967 at the age of 63 and was buried in the churchyard next to her husband, who had preceded her by two years. Her obituary made no mention of the triplets. Her children and grandchildren, scattered now across the country, have no idea that they have relatives they have never met, that their mother and grandmother once gave birth to three babies who were taken from her and raised by strangers, that somewhere in the world there are people who share their blood.

I have thought about reaching out to them, about telling them the truth, about connecting the branches of a family tree that was severed a century ago. But I have not done it. Not yet. Some secrets are kept for a reason, and I am not sure I have the right to undo what so many women worked so hard to protect.

Instead, I have framed the photograph and placed it on my mantelpiece next to my grandmother’s wedding picture and a snapshot of my mother as a young girl. When visitors ask about it, I tell them it is my great-great-grandmother with her triplets, taken in 1920, one of the only photographs we have from that era. They nod and move on, seeing nothing unusual, noticing nothing strange.

But sometimes, when I am alone, I take it down and hold it close. And I look at those hands—the ones that do not match. And I think about all the women who made me possible.

Rosemary, who loved so fiercely that she rewrote reality.

Clara, who carried a basket of babies across the fields and changed three lives forever.

Sarah, who turned her face to the wall and asked to be forgotten.

Elizabeth, who knew but never told.

Marjorie, who kept the secret until she found someone ready to hear it.

And I think about what it means to be a mother—not by blood, but by choice.

And I understand now that the hands in the photograph were never the point. The point was the arms that held them, the heart that loved them, the woman who looked into the camera with defiance in her eyes and dared the world to question what she had done.

The photograph is my inheritance. The story is my gift. And the hands that do not match are the proof that love is stronger than blood, stronger than truth, stronger than all the secrets we keep to protect the people we cannot bear to lose.

News

Antique Shop Sold a “Life-Size Doll” for $2 Million — Buyer’s Appraisal Uncovered the Horror

March 2020. A wealthy collector pays $2 million for what he believes is a rare Victorian doll. Lifesize, perfectly preserved,…

Her Cabin Had No Firewood — Until Neighbors Found Her Underground Shed Keeping Logs Dry All Winter

Clara Novak was 21 years old when her stepfather Joseph told her she had 3 weeks to disappear. It was…

My Wife Went To The Bank Every Tuesday for 20 Years…. When I Followed Her and Found Out Why, I Froze

Eduardo Patterson was 48 years old and until 3 months ago, he thought he knew everything about his wife of…

Her Father Lockd Her in a Basement for 24 Years — Until a Neighbor’s Renovation Exposed the Truth

Detroit, 1987. An 18-year-old high school senior with a promising future, vanished without a trace. Her father, a respected man…

“Choose Any Daughter You Want,” the Greedy Father Said — He Took the Obese Girl’s Hand and…

“Choose any daughter you want,” the greedy father said. He took the obese girl’s hand. Martha Dunn stood in the…

Her Son Was Falsely Accused While His Accuser Got $1.5 Million

He was a 17-year-old basketball prodigy. College scouts line the gym. NBA dreams within reach. But one girl’s lie shattered…

End of content

No more pages to load