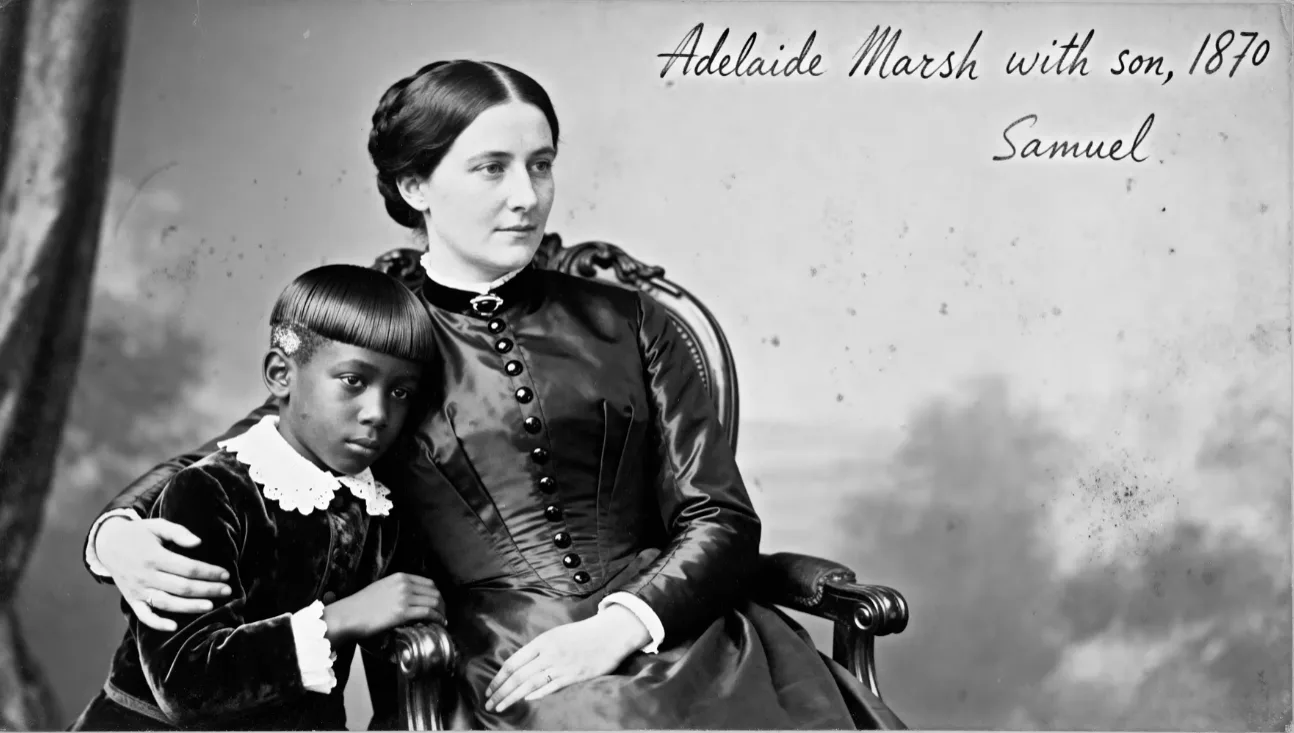

At first glance, it is a beautiful image. A woman in silk, a child leaning into her shoulder, the soft blur of a studio backdrop behind them. It looks like love. It looked like love for over 150 years, until one archivist could not stop staring at the top of that boy’s head.

Eleanar Vance had been cataloging photographs at a historical society in Richmond for 11 years. She had handled thousands of images from the antebellum and Reconstruction periods. Everything from daguerreotypes of Confederate officers to cabinet cards of newly freed families standing stiff and proud outside their first owned homes. She knew what to expect from photographs of this era. She knew the poses, the props, the elaborate staging meant to communicate status and respectability.

But the image she pulled from a donated estate collection in the spring of 2019 made her pause in a way nothing had in years. The photograph was a cabinet card, roughly 4×6 inches, mounted on thick card stock with the photographer’s name embossed in gold script along the bottom edge.

The woman in the portrait appeared to be in her early 30s, dressed in a dark silk dress with jet buttons running from collar to waist. Her hair was parted in the center and pulled back in a style typical of the early 1870s. She was seated in a carved wooden chair, and her left arm was wrapped around a young boy who stood beside her, leaning into the curve of her body.

The boy looked to be about 6 or 7 years old. His clothes were fine—a little velvet suit with a white lace collar, the kind of outfit a wealthy family might dress their cherished child in for a special occasion. His skin was brown. His features suggested African ancestry, and his head was tilted slightly toward the woman’s shoulder in what looked, at first glance, like a gesture of genuine affection.

Eleanar had seen photographs like this before. Mixed-race families existed throughout American history, even when laws and customs forbade acknowledging them openly. She assumed this might be one of those images, a quiet record of a relationship that could not be spoken aloud in its own time.

But something about the boy’s hair kept pulling her eye back. It was straight. Not loosely curled or wavy, which might occur naturally in a child of mixed heritage. Straight. Flat. Almost plastered to his scalp in a way that looked painful. And along the hairline, just above his left ear, Eleanar noticed a faint discoloration—a chemical burn, perhaps, or the remnant of something worse.

She leaned closer, adjusting the angle of her magnifying lamp, and felt her stomach tighten. The hair did not look like it had grown that way. It looked like it had been forced.

Eleanar Vance had spent more than a decade learning to read photographs the way other people read books. She understood that every element of a 19th-century studio portrait was deliberate. The backdrops, the props, the arrangement of hands and bodies—all of it was staged to communicate something specific to the viewer. Wealth, piety, familial harmony, respectability. Nothing was accidental.

So when something in an image did not fit the expected pattern, it usually meant there was a story the photograph was not telling directly. She had seen photographs where the “wrong” detail was a set of manacles half-hidden behind a chair leg. She had seen portraits where the “loyal servant” standing behind a white family was positioned in a way that revealed, on closer inspection, the iron collar around their neck. She had learned to look for the things that did not belong, the objects and poses that disrupted the careful performance of normality.

But she had never seen anything quite like this boy’s hair.

She removed the cabinet card from its protective sleeve and turned it over. On the back, in faded pencil, someone had written a name and a date: Adelaide Marsh with son, 1870. Below that, in different handwriting, was a single word that had been partially erased but was still legible if she held it at the right angle. The word was Samuel.

Two names. Mother and son, according to the inscription. But the erasure of Samuel’s name, the deliberate attempt to make it disappear, suggested that someone, at some point, had wanted to undo whatever claim this photograph made about their relationship.

Eleanar set the card down on her worktable and stared at it for a long time. She had a feeling—one she had learned to trust over the years—that this was not just a portrait of a mother and her child. This was evidence of something else entirely. And if she did not pursue it, whatever truth was buried here would stay buried.

The photographer’s stamp on the card read Whitmore and Company, Richmond. Eleanar began there, pulling city directories from the 1860s and 1870s to trace the studio’s history. She found it listed on Broad Street from 1858 through 1879, run by a man named Thomas Whitmore, who advertised “portraits of distinction for families of quality.” The phrasing was typical of the era, designed to signal that the studio catered to wealthy white clientele.

But a deeper search through Whitmore’s business records, which had been donated to a university archive in the 1990s, revealed something more interesting. Whitmore had also maintained a separate ledger for what he called “special commissions.” These were portraits taken for clients who did not want their names recorded in the main appointment book. The entries were sparse—just initials and dates and occasional notes about payment. But one entry, dated March 1870, caught Eleanar’s attention.

AM. Portrait with Ward. Hair preparation required, extra fee.

Ward. Not son. And hair preparation.

Eleanar felt the pieces beginning to click into place, though the picture they were forming was not a comfortable one. She contacted a colleague at a university in Washington, a historian named Dr. Lorraine Okonkwo, who specialized in the post-Emancipation period and the legal mechanisms white families used to maintain control over Black children after slavery officially ended.

Dr. Okonkwo had spent years documenting the practice of “apprenticing” Black children to their former enslavers—a system that allowed white families to keep Black minors as unpaid laborers under the guise of providing them with training and care. She had also written about the related phenomenon of “companion children”—Black children who were kept in white households not for labor but for companionship, dressed in fine clothes and displayed as evidence of the family’s benevolence.

When Eleanar sent her a high-resolution scan of the photograph, Dr. Okonkwo responded within hours.

“I’ve seen images like this before,” she wrote. “The clothing, the pose, the proximity to the white woman—it all fits the pattern. But the hair is what makes this one unusual. Most companion children were photographed with their natural hair, often exaggerated or styled to emphasize their difference from the white family members. Straightening a Black child’s hair like this would have been painful and unusual for the period. It suggests the family wanted to erase visible markers of his race, to make him appear more like a biological child. That is a different kind of violence than simple exploitation. It is an attempt at erasure.”

Eleanar began searching for more information about Adelaide Marsh. The name appeared in Richmond city directories from 1865 through 1882, listed at a substantial address in the Church Hill neighborhood. Census records from 1870 showed the household consisting of Adelaide Marsh, aged 32, listed as head of household; her widowed mother, Margaret Marsh, aged 58; and one servant, a Black female named Celia, aged 45. There was no child listed in the household at all.

This was not unusual for the period. Black children living in white households were often deliberately excluded from official records or listed under ambiguous terms that obscured their actual status. But the absence of any child in a census taken the same year as the photograph raised questions. If Samuel was Adelaide’s son, legally or otherwise, why was he not counted among the household members? And if he was not her son, what exactly was he?

Eleanar dug deeper into the Marsh family history. She found that Adelaide’s husband, a cotton merchant named Walter Marsh, had died in 1864 during the last year of the Civil War. His will, filed with the Richmond Probate Court, made provisions for his wife and explicitly mentioned “all servants and their issue currently held by the estate.” The Marshes had been enslavers, and according to the will, those enslaved people had not been freed upon Walter’s death, but transferred to Adelaide’s ownership.

Among the names listed in an inventory attached to the will was a woman named Celia, age 39 at the time of the inventory, and her daughter, name not given, age 4. There was no mention of a son. But four years later, the census showed Celia still in the household at age 45 with no daughter present—and the photograph showed a boy of about six or seven dressed in velvet, leaning into Adelaide Marsh’s shoulder as if she were his mother.

Eleanar contacted Dr. Okonkwo again with her findings. The historian’s response was measured but grim.

“This is consistent with a pattern I’ve documented in dozens of cases. After Emancipation, some white families retained Black children even when the adults in their families left or were forced out. The children were young enough to be controlled. And in some cases, the white family would claim legal guardianship through the apprenticeship system. But the most troubling cases are the ones where no legal mechanism was used at all. The white family simply kept the child. Sometimes claiming them as orphans, sometimes presenting them as adopted, and sometimes, as this photograph suggests, trying to pass them off as biological children. The hair straightening would fit that last category. It was an attempt to make the child’s race less visible.”

Dr. Okonkwo explained the broader context that made such arrangements possible. In the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, Virginia and other former Confederate states passed a series of laws known as the Black Codes, designed to restrict the freedom of newly emancipated people and force them back into labor arrangements that differed from slavery in name only. One of the most insidious provisions allowed courts to apprentice Black children to white employers—often their former enslavers—if the children were deemed to be orphans, abandoned, or without adequate means of support. The definition of “adequate means” was left to white judges, who frequently ruled that Black parents who were themselves struggling to survive in the devastated post-war economy were unfit to care for their children.

But even this legal framework did not account for all the children who remained in white households. Some were kept through informal arrangements, verbal agreements, or simple coercion. A Black mother working as a domestic servant might be told that if she wanted to keep her position, her child would need to stay in the household as well. The child might be presented to visitors as a ward, a companion, or sometimes, as in the case of the Marsh photograph, as something more ambiguous. Still, the practice was common enough that it had its own vocabulary. Yard children. House children. Pet children. Terms that made the arrangement sound benign while obscuring its fundamental violence.

“The hair is what makes this case particularly disturbing,” Dr. Okonkwo continued in a follow-up call. “Hair straightening for Black people in this era was rare and painful. The most common method involved lye-based compounds that could cause severe burns if left on too long. For a child of six or seven to be subjected to that process repeatedly, to maintain the appearance of straightened hair, would have been genuinely traumatic. It suggests the family was not simply keeping the child as a companion or servant, but actively trying to transform him into something else. They were trying to unmake his identity.”

Eleanar found herself returning to the photograph again and again, studying the boy’s face for some sign of what he might have been feeling in that moment. His expression was difficult to read. The long exposure times of the era meant that subjects had to hold still for several seconds, which often resulted in blank or strained expressions. But there was something in the set of his mouth, a tightness that might have been discomfort—or might have been something else entirely. She wondered if his scalp was still burning from whatever chemical had been used to flatten his hair. She wondered if he understood why he was being dressed in velvet and posed beside this woman. She wondered if he remembered his mother, and whether his mother had had any choice in letting him go.

The next step required a visit to Richmond, to the church where the Marsh family had been members. Eleanar made the trip in early summer, driving down from her office in the Shenandoah Valley to meet with the archivist at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, one of the oldest and wealthiest congregations in the city. The church occupied a prominent position on Grace Street, its white steeple visible for blocks in every direction. During the Civil War, Jefferson Davis himself had worshiped here, and the pews were still marked with small brass plaques bearing the names of the families who had purchased them generations ago. The Marsh name appeared on one such plaque in the third row from the front.

The church had maintained meticulous records of births, deaths, marriages, and baptisms going back to the 18th century. These records had served a dual purpose in the antebellum era: they documented the spiritual lives of the white congregation, but they also sometimes noted the baptisms of enslaved people owned by church members. These entries were typically brief and often lacked surnames, recording only a first name, the owner’s name, and the date. They were, in their own way, property records disguised as religious documents.

If Samuel had been baptized there, or if any official record had been made of his relationship to Adelaide Marsh, it would be in those ledgers.

The archivist, a retired schoolteacher named Mrs. Dorothy Hail, was initially skeptical of Eleanar’s inquiry.

“The Marsh family were generous benefactors of this church for generations,” she said, leading Eleanar through a corridor lined with portraits of former rectors. “I’m not sure what you expect to find that would be of historical significance.”

But when Eleanar showed her the photograph, Mrs. Hail’s expression changed. She studied the image for a long moment, then looked up at Eleanar with something that might have been recognition.

“I’ve seen this boy before,” she said quietly. “Not in person, obviously. But there’s another photograph in the collection.”

The second photograph, which Mrs. Hail retrieved from a storage room in the church basement, showed the same boy about ten years older. He was dressed in the plain dark suit of a household servant, standing behind a seated group of white women at what appeared to be a church function. The women were smiling, fanning themselves against what must have been summer heat, their dresses light-colored and their expressions easy. Behind them, Samuel stood at rigid attention. His hair was short now, natural, tight curls visible even in the faded image. He was not looking at the camera. He was looking down at the floor, and his hands were clasped in front of him in a posture of rigid stillness. There was no velvet, no lace collar, no tender lean into anyone’s shoulder. The companion child had become something else.

Eleanar studied the two photographs side by side, trying to reconcile them. The boy in velvet and the servant in dark wool. The straightened hair plastered painfully to a small skull, and the natural curls of a teenager who had been allowed finally to look like himself. The possessive embrace and the empty space between bodies. It was as if she were looking at two different people—except the face was unmistakably the same. Those same eyes, that same shape of the jaw. But something in the expression had hardened in the intervening decade. Whatever softness had been present—or performed—in the earlier image was gone entirely. In its place was something more guarded, more watchful, more aware of the camera’s gaze and what it could be used to prove.

The church records confirmed what Eleanar had begun to suspect. Samuel had never been legally adopted by Adelaide Marsh. He had never been baptized as her son. Instead, the record showed a single entry dated 1876, noting the “return of a colored ward named Samuel to his people at the request of his mother, Celia,” who had apparently remained in the Marsh household as a domestic servant throughout the years her son was being displayed as Adelaide’s companion. The entry was terse, almost bureaucratic, but its implications were devastating.

For six years, Celia had watched her son be dressed up and paraded as another woman’s child. She had watched his hair be burned straight. She had watched him posed for portraits that erased her existence entirely. And then, finally, she had found a way to get him back.

Dr. Okonkwo helped Eleanar locate records from a Black church in Richmond that had been founded by formerly enslaved people in 1866. The church, known in its early years simply as the Colored Baptist Church of Richmond, had been established in the basement of a former warehouse just months after the end of the war. Its founding members were men and women who had spent their entire lives in bondage, who had been forbidden by law from learning to read and write, who had been denied the right to marry or to keep their children. And one of the first things they did with their freedom was build an institution that would record their existence in their own words.

The church had kept its own membership rolls, separate from the white churches that had refused to accept Black congregants as full members, or that had relegated them to segregated balconies where they could hear the sermon but not participate in the sacraments. These rolls were more than simple lists of names. They recorded marriages that had been denied legal recognition under slavery. They recorded the births of children who would never be sold away. They recorded deaths and memorialized the lives that had been lived, brief as some of them were. And sometimes, they recorded reunions.

In those rolls, Eleanar found Celia’s name listed as a founding member, along with a note that she had been “reunited with her son Samuel” in 1876. The entry was brief—just a few lines—but the language was deliberate. Reunited. Not received or acquired or any of the euphemisms white record-keepers might have used. Reunited implied a separation that had been wrong, a relationship that had existed before and was now being restored. It implied that Celia had always been Samuel’s mother, even during the years when a white woman had dressed him in velvet and called him son.

Another entry, dated 1879, recorded Samuel’s marriage to a woman named Hannah. And a third entry, from 1882, noted the birth of their first child, a daughter named Eleanor.

The discovery that the boy in the photograph had survived, had reclaimed his identity, had built a family and a life beyond the Marsh household, was both a relief and a complication. It meant the story did not end with his erasure, but it also raised questions about how to tell that story now, more than a century later, when the descendants of all the people involved might still be living.

Eleanar Vance brought her findings to the historical society’s director, a man named Richard Townsend, who had hired her a decade earlier and generally trusted her judgment. She laid out the photographs, the records, the correspondence with Dr. Okonkwo, and explained what she believed the evidence showed: The 1870 portrait was not a picture of a mother and son. It was a picture of a white woman and a Black child she had kept as a companion, a living doll whose hair had been chemically straightened to make him appear more like her own offspring. And the inscription on the back—Adelaide Marsh with son—was not a record of biological relationship, but a claim of ownership disguised as affection.

Townsend listened carefully, examined the evidence, and then leaned back in his chair with a sigh.

“This is going to be complicated,” he said. “The Marsh family were major donors to this institution for generations. Their descendants are still involved with the board. If we re-contextualize this photograph the way you’re suggesting, there are going to be people who are very unhappy.”

“There are people who are very unhappy already,” Eleanar replied. “They just happen to be the descendants of Samuel and Celia, not the descendants of Adelaide Marsh. And their unhappiness has been invisible for 150 years.”

The board meeting took place three weeks later. Eleanar presented her research to a room full of people who shifted uncomfortably in their seats as she showed them the two photographs side-by-side: the velvet-clad companion child of 1870, and the servant of 1880. She explained the hair straightening, the absence from census records, the church entries that documented Celia’s long campaign to reclaim her son. She quoted Dr. Okonkwo’s analysis of the companion child phenomenon and its relationship to the broader systems of racial control that persisted long after Emancipation.

When she finished, the room was silent for a long moment. Then a woman near the back, someone Eleanar recognized as a descendant of the Marsh family, raised her hand.

“I don’t understand what you want us to do with this information,” she said. Her voice was controlled, but there was an edge to it. “You’re asking us to essentially accuse my ancestors of kidnapping a child based on what? A photograph and some church records?”

“I’m not accusing anyone of anything,” Eleanar said carefully. “I’m asking us to tell the truth about what this photograph shows. For decades, this image has been displayed with a caption that calls it ‘a portrait of a mother and son.’ That caption is not accurate. The boy was not Adelaide Marsh’s son. He was the son of a woman named Celia who worked in the Marsh household and who spent years trying to get him back. If we continue to display this image with the old caption, we are participating in the same erasure that was done to Celia and Samuel in their own time.”

The debate continued for over an hour. Some board members argued that the evidence was circumstantial, that Eleanar was reading too much into ambiguous historical records. Others worried about the optics of publicly “correcting” the record on a prominent local family. But a few, including a newer board member who taught African-American history at a local college, argued forcefully that the society had an obligation to tell accurate stories, even when those stories were uncomfortable.

In the end, a compromise was reached. The photograph would be re-displayed with a new, expanded caption that acknowledged the uncertainty about the relationship between the two subjects and provided context about the practice of “companion children” in the post-Civil War South. A small exhibition would be mounted around the image, featuring both photographs and excerpts from the church records that documented Samuel’s return to his mother. And the society would reach out to descendants of Samuel and Celia, if any could be found, to invite their participation in telling the fuller story.

Finding those descendants took another six months. Eleanar worked with a genealogist named Marcus Webb, who specialized in tracing African-American family lines—a painstaking process complicated by the deliberate destruction of records and the frequency with which Black families had been separated and scattered. Webb explained that tracing a lineage like Samuel’s required working backward and forward simultaneously, using whatever fragmentary documentation had survived: marriage licenses, death certificates, property records for those rare families who had managed to acquire land, school enrollment lists, fraternal organization membership rolls, church records from multiple congregations since families often moved as they followed economic opportunities or fled violence.

The search was further complicated by the Great Migration—the mass movement of Black Americans from the rural South to cities in the North and West that began in the early 20th century and continued for decades. Millions of people had left places like Richmond, seeking better wages, safer communities, and escape from the Jim Crow laws that governed every aspect of their lives. Their descendants might be anywhere now.

Marcus Webb traced Samuel’s line through census records to Baltimore in 1910, then to Philadelphia by 1920. The trail grew clearer after that. Samuel’s granddaughter had married a steelworker named Holland. Their children had stayed in Philadelphia, and eventually Webb found a woman named Patricia Holland living in the Germantown neighborhood—a retired nurse whose great-great-grandmother had been named Hannah, and whose family Bible included an entry for Hannah’s husband, Samuel: Born in bondage, stolen as a child, but returned to his mother by the grace of God.

Patricia Holland came to Richmond for the exhibition opening. She stood in front of the 1870 photograph for a long time, not speaking, her hand pressed against the glass case as if she could reach through it to touch the boy inside. When she finally turned to Eleanar, there were tears on her face, but she was smiling.

“My grandmother used to talk about him,” she said. “She called him ‘the stolen son.’ She said he never talked about those years, not to anyone, but that his mother, Celia, used to say the white woman dressed him up like a doll and burned his hair to make him look like something he wasn’t. We always thought it was just a story. We never knew there was a picture.”

The exhibition ran for four months and drew more visitors than any previous show at the historical society. Local newspapers covered the story, and several academic journals published articles about the “companion child” phenomenon, using the Marsh photograph as a case study. Dr. Okonkwo gave a lecture at the society to a packed auditorium, explaining how Samuel’s story fit into the broader pattern of white families maintaining control over Black children through means both legal and extra-legal in the years after Emancipation. She showed slides of other photographs that scholars had identified as depicting similar arrangements—images from Alabama and South Carolina and Mississippi, all featuring well-dressed Black children posed alongside white women who were not their mothers.

The exhibition also prompted a broader reckoning within the historical society itself. Staff members began reviewing other items in the collection that had been accessioned decades ago with minimal documentation or misleading descriptions. They found photographs labeled “family servant” that showed children too young to be working. They found portraits described as “nurse in charge” where the supposed nurse was barely older than the infant she held. They found images of Black people with no names attached at all, just descriptions like “domestic scene” or “household group.” Each of these items was now being researched, contextualized, and, where possible, connected to descendants who might have their own stories to add.

Richard Townsend, the director who had initially worried about donor relationships, told Eleanar that the exhibition had changed his understanding of what the society was supposed to do.

“We’ve been treating these photographs as artifacts,” he said. “Objects to be preserved and displayed. But they’re not just objects. They’re evidence. And for over a century, we’ve been presenting the evidence in a way that supported one version of events while silencing another. I don’t know how to undo all of that. But we have to start somewhere.”

But for Eleanar, the most important moment came near the end of the exhibition’s run, when Patricia Holland returned to Richmond with her daughter and two grandchildren. They stood together in front of the photograph—four generations of Samuel’s descendants, looking at the image of a boy who had been erased and reclaimed, stolen and returned.

The youngest grandchild, a girl of about seven—the same age Samuel had been when the photograph was taken—pointed at the image and asked her great-grandmother who the people were.

Patricia Holland knelt down beside her.

“That’s your great-great-great-great-grandmother’s son,” she said. “His name was Samuel. And the woman next to him is not his mother. His real mother was a woman named Celia, who loved him so much she spent years fighting to get him back. And she did. She got him back.”

The girl looked at the photograph again, then back at her great-grandmother.

“Why is his hair like that?” she asked.

Patricia Holland was quiet for a moment.

“Because they were trying to make him into something he wasn’t,” she said finally. “But it didn’t work. He always knew who he was. And now we do, too.”

Photographs lie. That is not a new observation, but it bears repeating every time we look at an old image and assume we understand what we are seeing. The camera captures a moment, but that moment is always staged, always framed, always a performance of something the subjects and the photographer want us to believe. A white woman in silk posing with a Black child in velvet. A tender lean of a small body into a maternal embrace. These are images that tell a story of love and family and belonging.

But the details tell a different story. The burned hairline. The absence from the census. The separate ledger entry for “special commissions.” The church record noting a return that should never have been necessary.

Samuel’s photograph is not unique. Archives and attics and museum storage rooms across the country hold thousands of images like it. Portraits that were staged to show benevolence and affection, but that actually document something much darker. Children dressed as companions and displayed as evidence of a slaveholder’s kindness. Families posed together to obscure the violence that bound them. Hair straightened, skin lightened, identities erased to maintain the fiction that what was happening was normal, was natural, was good.

Every one of those photographs is a crime scene. And every one of them is also a record—if we learn how to read it—of the people who survived.

Samuel survived. Celia survived. Their descendants survived. And they carried the story forward, even when the photograph tried to erase it.

The next time you look at an old portrait and feel a warm sense of connection to the past, look closer. Look at the hands. The hair. The edges of the frame. Look for what does not belong. Look for the story the image is trying not to tell.

Because that story belongs to someone. And they have been waiting a very long time for someone to notice.

News

Antique Shop Sold a “Life-Size Doll” for $2 Million — Buyer’s Appraisal Uncovered the Horror

March 2020. A wealthy collector pays $2 million for what he believes is a rare Victorian doll. Lifesize, perfectly preserved,…

Her Cabin Had No Firewood — Until Neighbors Found Her Underground Shed Keeping Logs Dry All Winter

Clara Novak was 21 years old when her stepfather Joseph told her she had 3 weeks to disappear. It was…

My Wife Went To The Bank Every Tuesday for 20 Years…. When I Followed Her and Found Out Why, I Froze

Eduardo Patterson was 48 years old and until 3 months ago, he thought he knew everything about his wife of…

Her Father Lockd Her in a Basement for 24 Years — Until a Neighbor’s Renovation Exposed the Truth

Detroit, 1987. An 18-year-old high school senior with a promising future, vanished without a trace. Her father, a respected man…

“Choose Any Daughter You Want,” the Greedy Father Said — He Took the Obese Girl’s Hand and…

“Choose any daughter you want,” the greedy father said. He took the obese girl’s hand. Martha Dunn stood in the…

Her Son Was Falsely Accused While His Accuser Got $1.5 Million

He was a 17-year-old basketball prodigy. College scouts line the gym. NBA dreams within reach. But one girl’s lie shattered…

End of content

No more pages to load