Bass Reeves knew they were coming 3 days before they arrived. He’d heard the whispers in town, seen the way men looked at him when he brought in a white outlaw. So when 12 KKK members surrounded his camp that night, Bass wasn’t surprised. He’d chosen that exact spot, counted every tree, measured every shadow. When their leader said, “Tonight you die, boy.” Bass smiled in the darkness because they just walked into his trap. What the clan didn’t understand was simple. You don’t hunt Bass Reeves. Bass Reeves hunts you.

August 12th, 1884. The town of Fort Smith, Arkansas was buzzing with tension. Bass Reeves had just brought in three white outlaws alive, handcuffed, humiliated. For a black US marshal to arrest white men in 1884 was dangerous. For him to do it with the efficiency and authority Bass displayed, that was unforgivable. The outlaws had family. They had friends. And some of those friends wore white hoods at night.

Bass felt their eyes on him as he walked through town. He’d been a marshal for 2 years by then, and he understood how this worked. When you wore a badge and you looked like him, every arrest was personal. Every capture was an insult. Every day you stayed alive was a challenge to men who believed you had no right to exist, let alone carry federal authority. He heard them talking outside the general store, quiet voices that went silent when he walked past. He saw them watching from the saloon, their faces twisted with something uglier than hate. It was wounded pride. And wounded pride in a white man’s heart in 1884 Arkansas was a deadly thing. Bass knew what was coming. The only question was when.

3 days later, he had his answer. Bass was tracking a fugitive named William Dodd through the Arkansas wilderness. Dodd had killed a Creek family and stolen their horses. The warrant said dead or alive, but Bass preferred alive. Dead men couldn’t testify. Dead men couldn’t face justice. Dead men were easy. Bass had tracked Dodd to a clearing near the Poteau River. Dense forest on three sides, river on the fourth. It was good hunting ground, which is exactly why Bass chose to camp there that night. Even though Dodd was still 10 miles ahead, because Bass wasn’t hunting Dodd anymore, he was hunting the men who were hunting him.

He’d spotted them two days ago. 12 riders moving too carefully to be regular travelers, keeping their distance, but always there just at the edge of sight. They thought they were being clever. They thought Bass didn’t see them. Bass Reeves saw everything.

He made camp in the clearing as the sun went down, built his fire bigger than necessary, made coffee, ate beans straight from the can. He moved slowly, deliberately, making himself visible, making himself look vulnerable. A lone black man in the wilderness. No backup, no witnesses, just him and the darkness. It was perfect bait.

What those men didn’t know was that Bass Reeves had been preparing for this moment his entire life. He’d been born into slavery in 1838, spent his childhood as property owned by a man named George Reeves in Arkansas. He learned early that to survive, you had to be smarter than the people who owned you. You had to see three moves ahead. You had to turn their confidence into your advantage. When Bass was 14, his master took him on a hunting trip. George Reeves was drunk, mean, decided to beat Bass for some imagined offense. Bad decision. Bass fought back. Broke George Reeves’ nose. Maybe his jaw. Left him bleeding in the dirt. Then Bass ran. Not in panic, not in fear. With purpose. He disappeared into Indian territory. 14 years old, alone. No food, no weapon, no plan except survival. The Creek and Seminole tribes took him in. They taught him to track, to shoot, to move through the wilderness like smoke. For 2 years, Bass lived among them, learned their languages, learned their ways.

When the Civil War ended and slavery was abolished, Bass emerged from the wilderness a different man. He’d gone in as a boy running for his life. He came out as someone who understood a simple truth. The most dangerous man in any room is the one who’s already survived the impossible. Now, 26 years later, sitting by his campfire in that Arkansas clearing, Bass was about to teach that lesson again.

He heard them at 10:47 p.m. 12 horses moving into position. They were trying to be quiet, but Bass could hear everything. The creak of saddle leather, the nervous breathing of men preparing to kill, the metallic click of rifle hammers being cocked. Bass didn’t move, just sat there drinking his coffee, staring into the fire.

At 11 exactly, they revealed themselves. 12 men in white robes stepping out of the darkness into the firelight. Their leader was a big man, 6’3″, holding a coiled rope in one hand and a Colt revolver in the other.

“You made a mistake coming here, boy,” the leader said.

Bass took another sip of his coffee, set the cup down carefully, looked up at the 12 men surrounding him.

“One of us did,” he said quietly.

The clansmen laughed. It was the laughter of men who thought they’d already won.

“We got 12 guns pointed at you,” the leader said. “What you got?”

“I’ve got something better,” Bass replied. “I’ve got geography.”

Before anyone could process what that meant, Bass moved. Not toward the men, toward the fire. He kicked a burning log into the face of the nearest clansman. The man screamed, dropped his rifle, clutched his burning eyes. In the same motion, Bass drew both of his Colt .45s and dove behind a fallen tree he’d positioned earlier that afternoon.

The clansmen opened fire, 12 guns erupting in the darkness. But Bass wasn’t where they thought he was anymore. Their bullets tore through empty air, through the space where he’d been sitting two seconds ago. Bass fired back. Two shots, two men dropped. Now there were 10.

“Spread out!” the leader screamed. “He can’t get all of us.”

They were right. In an open fight, 12 against one, Bass would lose. That’s why this wasn’t going to be an open fight. That’s why he’d chosen this clearing. Bass had spent three days scouting this area. He knew every tree, every rock, every shadow. He’d carved hand holds into certain trees for climbing. He’d marked his sight lines. He’d even loosened the dirt in specific spots so he could hear footsteps approaching. The clansmen were shooting at darkness now, wasting ammunition, getting scared.

Bass moved like smoke through the forest. The moonlight barely penetrated the canopy, and he used that darkness like a weapon. He circled behind three men who’d clustered together for safety. They never heard him coming. Three shots, three bodies. Seven left.

“Where is he?” someone shouted, fear in the voice now.

“He’s just one man!” the leader yelled, but his voice cracked on the word ‘man’.

Bass was already gone, moving to his next position. He’d tied his horse a mile away before sunset. These men’s horses were scattered now, spooked by the gunfire. They had nowhere to run. Even if they tried, Bass knew this terrain. They didn’t. Two more clansmen made the mistake of running toward the river. Maybe they thought they could swim across, escape into the darkness on the other side. They made it 10 feet before Bass’s bullets found them. Five left.

The leader was shouting orders, but nobody was listening anymore. Fear had broken them. They were firing at sounds now, at shadows, at nothing. Bass picked off two more who’d separated from the group. Quiet shots in the darkness. Then silence. Three left.

By 1:00 a.m., it was over for all but one. The leader and two others had barricaded themselves behind a fallen tree. They were out of ammunition, terrified, waiting for dawn. Bass walked into their camp at 1:30. He wasn’t hiding anymore. Didn’t need to. His guns were drawn but pointed at the ground. He was giving them a chance to see him, to understand what had happened.

The leader looked at Bass like he was staring at a ghost. “How?” he whispered.

“You came to hunt me,” Bass said. “But you never asked yourselves a question. How does a black man survive as a US marshal for 2 years in Arkansas? How does he arrest white outlaws and live to tell about it?” He holstered one pistol, kept the other ready. “The answer’s simple. I don’t wait for the fight to come to me. I choose the ground. I choose the time. I choose everything. And when men like you come for me, thinking I’m an easy target,” he smiled. Not a friendly smile, a wolf smile. “I teach them what their granddaddies should have taught them. Underestimating the man you’re trying to kill is the fastest way to end up dead.”

Bass arrested two of them, handcuffed them to a tree. The third man, the leader, he let go.

“Why?” the leader asked, his voice broken.

“Because you’re going back to tell your people what happened here,” Bass said. “You’re going to tell them that 11 men came to lynch Bass Reeves and 11 men died or got arrested. You’re going to tell them that every time they come for me, I’ll be ready. Every time they think they’ve got me surrounded, I’m the one who chose the battlefield. And you’re going to make sure they understand something important.” He leaned close. “I’m not the hunted. I’m the hunter. And I’m always three steps ahead.”

The man rode away at dawn, broken, terrified, and alive, only because Bass Reeves allowed it. By sunrise, Bass had collected his prisoners, buried the dead, and written his report for Judge Parker in Fort Smith. Clean, detailed, professional. He didn’t mention that he’d planned the entire thing. Didn’t mention that he’d used himself as bait. Just stated the facts. Attacked by 12 members of a domestic terror organization. Defended myself. Two arrested, nine deceased. Returning to Fort Smith with prisoners.

When Bass rode into Fort Smith 3 days later with two handcuffed clansmen, word had already spread. The survivor had told his story, not with pride, with fear. The whispers changed after that. Men still hated Bass Reeves, but they didn’t try to ambush him anymore because the story of what happened in that Arkansas clearing became legend. The night Bass Reeves turned a lynch mob into a lesson. The night he proved that a badge in the hands of a dangerous man is the most powerful weapon in the world.

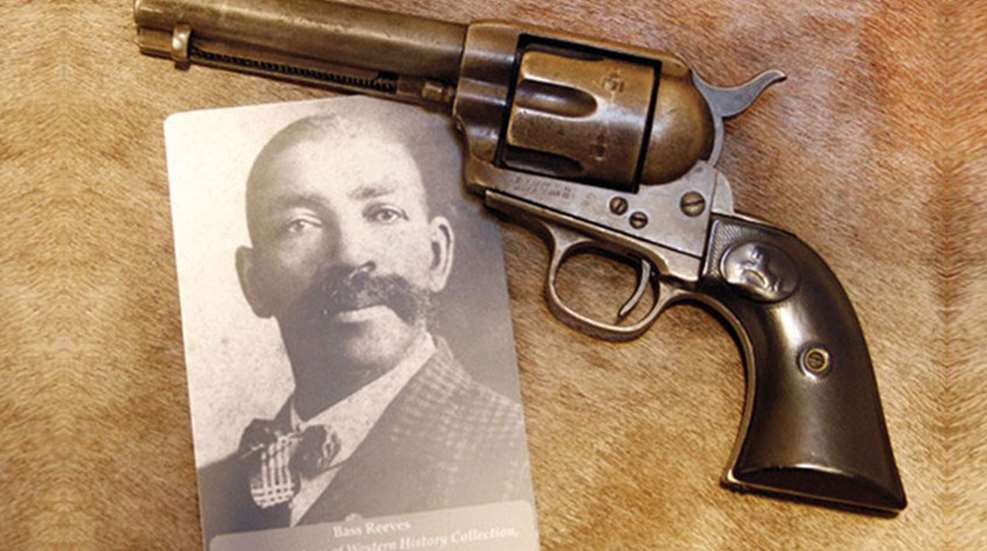

Bass Reeves served as a US marshal for 32 years. He arrested over 3,000 criminals. He killed 14 men in the line of duty. Every one of them was justified. Every one of them had a chance to surrender. Every one of them chose to fight instead. Bad choice. He never lost a prisoner. Never failed to bring back his man. And after that night in August 1884, nobody ever tried to ambush Bass Reeves in the darkness again because they’d learned, “You don’t surround Bass Reeves. Bass Reeves surrounds you.”

The KKK thought they were hunters. They thought a black man with a badge was easy prey. They were wrong. And by morning, 11 of them had paid for that mistake with their lives. Bass Reeves wasn’t just a marshal. He was a message, a declaration, a living proof that courage, intelligence, and skill don’t care about the color of your skin. That justice doesn’t bend to intimidation. That the most dangerous man in any fight is the one who’s already survived the impossible.

Bass Reeves. The man they couldn’t kill. The marshal they couldn’t intimidate. The legend they tried to bury.

News

🎰 Jackie Chan on Bruce Lee: Soul, Pressure, and the Birth of a New Martial Arts Cinema

For nearly a decade, the interview was thought to be lost. Buried on an old beta tape—relic technology from another…

🎰 The Kick That Ended an Era: How Holly Holm Shattered Ronda Rousey’s Invincibility

For years, Ronda Rousey was untouchable. She wasn’t just the face of women’s MMA—she was its unstoppable force. Opponents entered…

🎰 Dan Hooker doesn’t expect Paddy Pimblett to be around for long as his career will only get harder after UFC 324

Paddy Pimblett received a lot of praise after suffering his first loss inside the Octagon. ‘The Baddy’ showed tremendous heart…

🎰 A War Nobody Escaped: Justin Gaethje, Paddy Pimblett, and the Night Violence Took Over

“I saw what happened, and I won’t let it slide.” This wasn’t the first time Justin Gaethje flirted with controversy,…

🎰 Conor McGregor praises Khabib Nurmagomedov’s ‘legend’ pal weeks after criticizing rival for ‘scam’ on his platform

Conor McGregor has heaped praise on Telegram founder Pavel Durov just weeks after slamming his greatest rival for a venture…

🎰 Chaos vs. Consequence: Justin Gaethje, Paddy Pimblett, and a Fight That Split the MMA World

“I saw what happened, and I won’t let it slide.” This wasn’t the first time Justin Gaethje flirted with controversy,…

End of content

No more pages to load