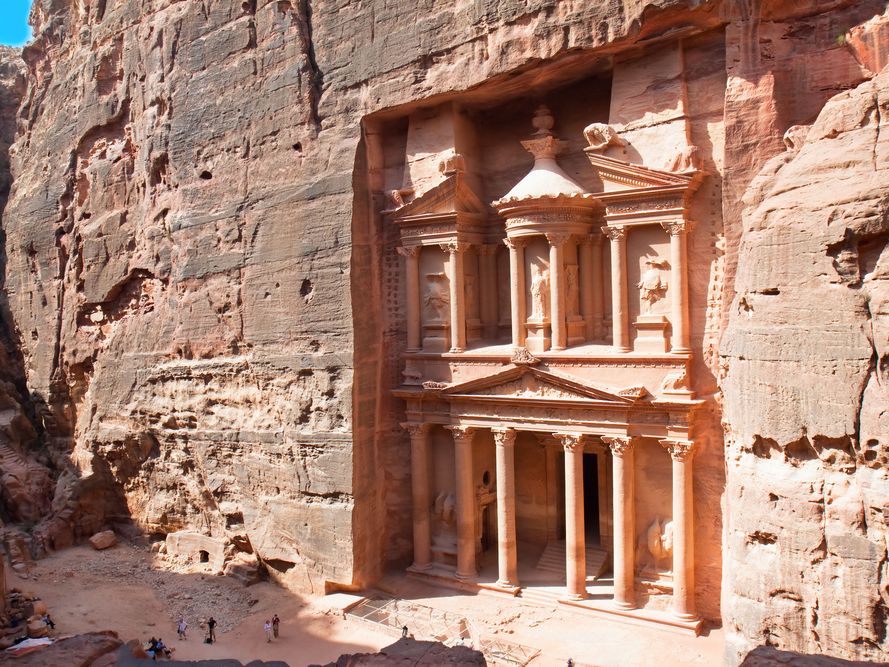

Petra’s Enigma: How Ancient Engineers Carved a Masterpiece Beyond Modern Understanding

Petra’s Treasury façade was carved from the top down, a method requiring the removal of roughly 8,000 cubic meters of solid sandstone—equivalent to about 20,000 tons of rock—using Bronze Age tools like copper chisels and stone hammers.

This subtractive sculpture demanded near-perfect precision; every mistake was permanent.

The columns, each 12 meters tall, feature entasis—subtle convex curves designed to correct optical illusions, a mathematical refinement that requires precise measurement and symmetry.

Modern stonemasons attempting to replicate even small sections of Petra struggle to achieve the same surface smoothness or precision with period-appropriate tools.

Petra’s surfaces approach a polish comparable to modern stonework done with diamond abrasives and power tools—a level of finish that ancient hand grinding would have required years to accomplish.

Recent 3D laser scanning and microscopic analyses conducted in 2025 have revealed astonishing details.

The Treasury’s surfaces show uniform smoothness with deviations as small as 2 to 3 millimeters across hundreds of square meters.

Toolmark analyses present a puzzling picture: some marks correspond with known ancient percussion tools, but others are too uniform and controlled, suggesting unknown techniques or mechanical guidance.

Several surfaces display almost no tool marks at all, defying explanation by conventional methods.

Adding to the enigma is the lack of archaeological evidence for extensive scaffolding.

Carving a 40-meter vertical cliff face with such precision would typically require complex scaffolding systems, yet only minimal holes or anchor points exist.

Theories propose rope suspension or temporary platforms, but these seem insufficient for the level of accuracy and safety needed.

Measurement and proportion posed another challenge.

Creating identical columns with perfect entasis requires continuous, precise measurement—a daunting task without modern surveying tools.

Researchers speculate the Nabataeans used full-scale templates, ropes, plumb lines, and water levels, but how they maintained accuracy over such heights and depths remains unclear.

Petra’s water management systems, featuring carefully graded channels and dams, demonstrate the Nabataeans’ advanced engineering skills.

These hydraulic feats required precise surveying and geometric calculations, hinting that similar expertise might have guided the architectural carving.

Intriguingly, quality analyses show Petra’s earliest facades, including the Treasury, exhibit the highest craftsmanship—exceeding later works in precision and finish.

This contradicts typical expectations of skill improving over time.

Possible explanations include early master craftsmen possibly from foreign cultures, lost techniques inherited from predecessors, or even earlier unknown civilizations whose knowledge faded over time.

Unfinished facades scattered around Petra provide clues to the carving process: initial rough excavation, intermediate shaping, and final smoothing.

Some incomplete works display more precise initial carving than finished facades elsewhere, suggesting varying skill levels or workshops.

Petra’s interior spaces also reveal deliberate acoustic design, with reverberations enhancing ceremonies.

This suggests a sophisticated understanding of sound behavior, reinforcing the city’s architectural mastery.

The Nabataeans’ position as cultural and trade intermediaries exposed them to Greek, Roman, Egyptian, and Arabian influences, reflected in Petra’s eclectic architectural style.

Yet, no known ancient culture matches Petra’s unique combination of scale, precision, and surface finish.

Comparisons with Egyptian rock-cut temples, Lycian tombs, or Indian rock-cut architecture highlight differences in scale, technique, and finish.

Petra stands alone in its architectural ambition and technical execution.

In conclusion, Petra remains a profound archaeological and engineering mystery.

The 2025 studies highlight tool marks inconsistent with known ancient methods, surface finishes beyond hand grinding capabilities, and architectural precision achieved without clear evidence of scaffolding or measurement systems.

Modern craftsmen cannot replicate Petra’s finest work within reasonable timeframes using period tools.

These findings suggest the Nabataeans possessed advanced, now-lost stoneworking techniques, possibly inherited or developed beyond current understanding.

Petra’s creation challenges assumptions about ancient technology and the linear progression of craft skills, leaving us to marvel at a civilization whose secrets endure two millennia later.

News

Exposed at Sundance: Why Meghan Markle’s Star Power Is Fading Fast

Meghan Markle’s Sundance Disaster: When the Spotlight Turns Against Her Meghan Markle’s documentary Cookie Queens, which she executive produced, premiered…

Leaked Yacht Footage Exposes Meghan Markle’s Secret Life Before Prince Harry

The Yacht Video Meghan’s Lawyers Paid Millions to Bury Has Just Leaked Just one day ago, a video surfaced online…

Inside Iran’s Jesus Revolution: How Christianity Is Quietly Toppling Theocratic Control

Iran’s Jesus Revolution: Over One Million Muslims Embrace Christianity Amidst Unrest Iran, the largest Shiite Muslim state, is traditionally seen…

What Really Happened in Pickle Wheat’s Truck? The Shocking Truth Behind the Viral Rumor

The Truth Behind the Shocking Discovery Rumor in Pickle Wheat’s Truck Cheyenne Picklewheat has captured the hearts of Swamp People…

27 Years Buried Secrets: What Princess Diana’s Tomb Revealed That Shattered Official Stories

Unveiling the Secrets: What Happened When Princess Diana’s Tomb Was Opened After 27 Years? Princess Diana’s death in 1997 sent…

From Mockery to Miracles: How Jesus Transformed Four Devout Muslims in One Night

When Mockery Meets Miracles: Four Muslim Men’s Life-Changing Encounter with Jesus at Communion Ysef grew up deeply rooted in Islamic…

End of content

No more pages to load