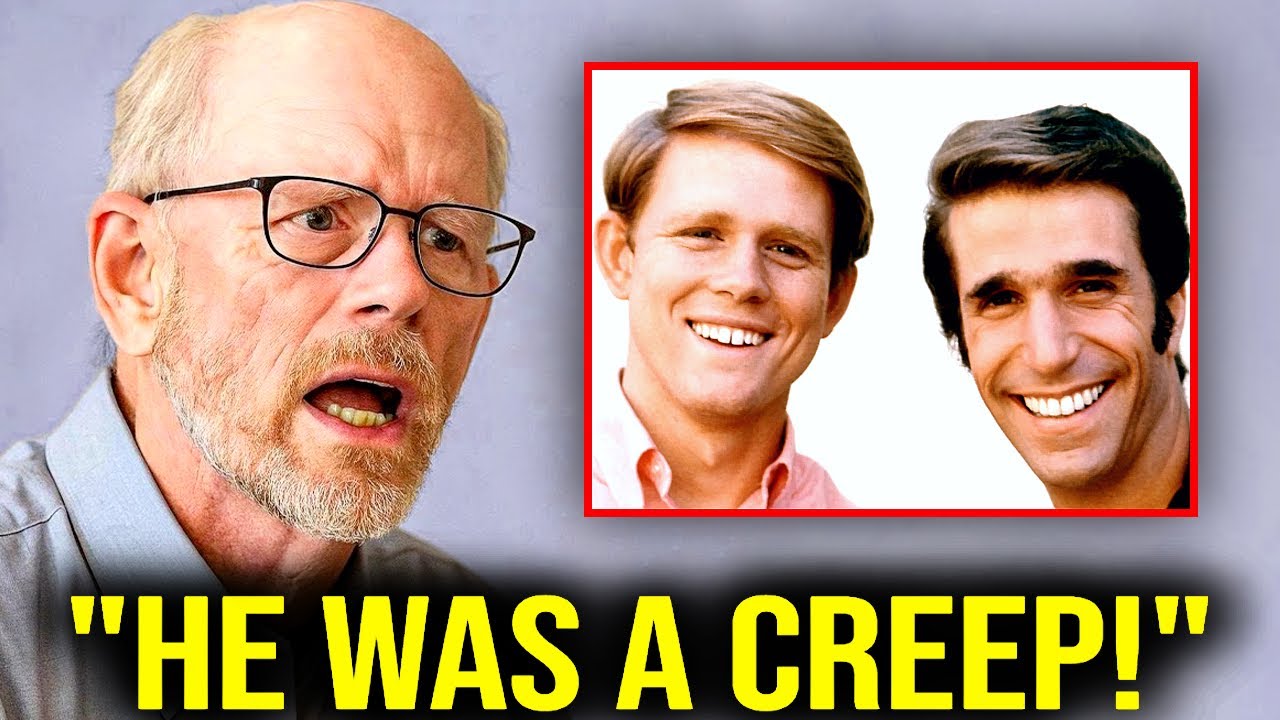

Why Ron Howard Quietly Left Happy Days at the Height of Its Fame

For decades, fans of Happy Days believed Ron Howard’s departure was simple and unremarkable.

The official explanation sounded harmless: he wanted to pursue directing.

A natural progression. A polite exit. Nothing more.

But according to Howard himself, that explanation barely scratched the surface.

The truth was far more layered, far more tense, and far more revealing about how Hollywood really works when a young star outgrows the role that made him famous.

When Happy Days premiered in 1974, it quickly became a cultural phenomenon.

America fell in love with its nostalgia, its optimism, and its characters.

Richie Cunningham, played by Ron Howard, was the emotional center of the show—the clean-cut teenager audiences trusted.

Howard, already famous from The Andy Griffith Show, seemed destined to remain America’s favorite son forever.

But success has a way of quietly reshaping power dynamics.

As the seasons progressed, Happy Days began to change.

What started as an ensemble-driven coming-of-age story gradually shifted its focus.

Fonzie, portrayed by Henry Winkler, exploded in popularity.

Audience reactions were overwhelming.

Ratings soared whenever he appeared.

Network executives noticed—and they adjusted accordingly.

Storylines began orbiting around Fonzie.

Screen time shifted.

Creative priorities followed the ratings, not the original vision.

Richie Cunningham, once the heart of the series, slowly found himself standing on the sidelines of his own show.

Ron Howard felt it.

In later interviews, Howard confirmed that his decision to leave was not sudden, nor was it emotional in the way fans imagined.

It was strategic.

Calculated.

Necessary.

He saw what many young actors fail to recognize until it’s too late: the longer you stay in a role that’s shrinking, the harder it becomes to redefine yourself.

Howard was not angry.

He did not resent Winkler.

In fact, he has repeatedly expressed respect for his co-star.

But he understood something crucial—Happy Days was no longer the show he had signed on to, and Richie Cunningham was no longer evolving.

At the same time, Howard was developing a quiet obsession behind the camera.

While others relaxed between takes, he studied scripts, camera angles, and editing techniques.

He watched directors work.

He asked questions.

He learned.

Acting had given him access, but directing offered something far more intoxicating: control over story, tone, and vision.

And that control mattered.

Howard has since confirmed that remaining on Happy Days would have delayed, if not destroyed, his chances of being taken seriously as a filmmaker.

In the late 1970s, television actors—especially those associated with wholesome sitcoms—were rarely respected in Hollywood’s directing circles.

Staying too long risked being permanently labeled.

The final push came when Howard realized that even his own character’s future was no longer in his hands.

Richie’s arcs had become repetitive.

Growth was limited.

The role that once represented opportunity had become a ceiling.

Leaving at the peak felt dangerous.

Happy Days was still a ratings juggernaut when Howard exited in 1980.

Walking away from guaranteed fame, steady income, and national visibility went against every rule young actors were taught to follow.

But Howard wasn’t chasing comfort.

He was chasing longevity.

What shocked many fans was how quietly he left.

Richie Cunningham was written out respectfully, and Howard stepped away with grace.

That silence was intentional.

Howard understood that bitterness closes doors faster than failure.

The aftermath, however, was unforgiving.

Hollywood did not immediately welcome him as a director.

Studios were skeptical.

Executives doubted that “Richie Cunningham” could command a film set.

Howard faced rejection after rejection.

The transition was brutal, humbling, and far from guaranteed.

But then came Night Shift. Then Splash. Then Cocoon.

And eventually, Apollo 13, A Beautiful Mind, and an Academy Award.

Looking back, Howard has confirmed what many suspected but few understood at the time: leaving Happy Days was an act of survival, not ambition.

Staying would have meant comfort at the cost of growth.

Fame at the expense of future.

What makes Howard’s story so compelling is not scandal, but restraint.

In an industry where egos often combust publicly, he chose discipline.

He recognized when the spotlight was no longer serving him—and stepped out of it before it defined him forever.

Today, Happy Days remains beloved, frozen in amber as a symbol of simpler times.

But Ron Howard refused to remain frozen with it.

He left not because the show failed him, but because he refused to fail himself.

And that decision, quietly made decades ago, changed Hollywood history.

News

A Homeless Girl, Her Loyal Dog, and the Moment Simon Cowell Became Human

Tears, Courage, and Gold: The Performance That Melted Simon Cowell’s Toughest Walls The studio lights burned bright over the…

The 11-Year-Old Prodigy Who Defied the Rules and Earned Two Golden Buzzers

History in Gold: The Child Guitarist Whose Performance Shocked Britain’s Got Talent The theater lights dimmed into a hush…

Whispers in the Spotlight: The Myths, Legends, and Power of Pearl Bailey

Pearl Bailey: The Shadowed Mystique Behind a Reign of Black Hollywood Royalty Pearl Bailey’s name has long shimmered in…

Brigitte Bardot Dies at 91 — From French Cinema’s Legendary Sex Symbol to Controversial Icon

BB’s Final Curtain: The Life, Fame and Complex Legacy of Brigitte Bardot Brigitte Bardot — a name whispered in…

Before His Death, Robert Redford Finally Confirmed the Truth About Paul Newman

Robert Redford’s Final Admission About Paul Newman Changes Everything For decades, the relationship between Robert Redford and Paul Newman…

From Shy Audition to Historic Victory: Darci Lynne’s Unstoppable AGT Journey

The Girl Who Changed AGT Forever: How Darci Lynne Went from Audition to Champion When Darci Lynne first walked…

End of content

No more pages to load