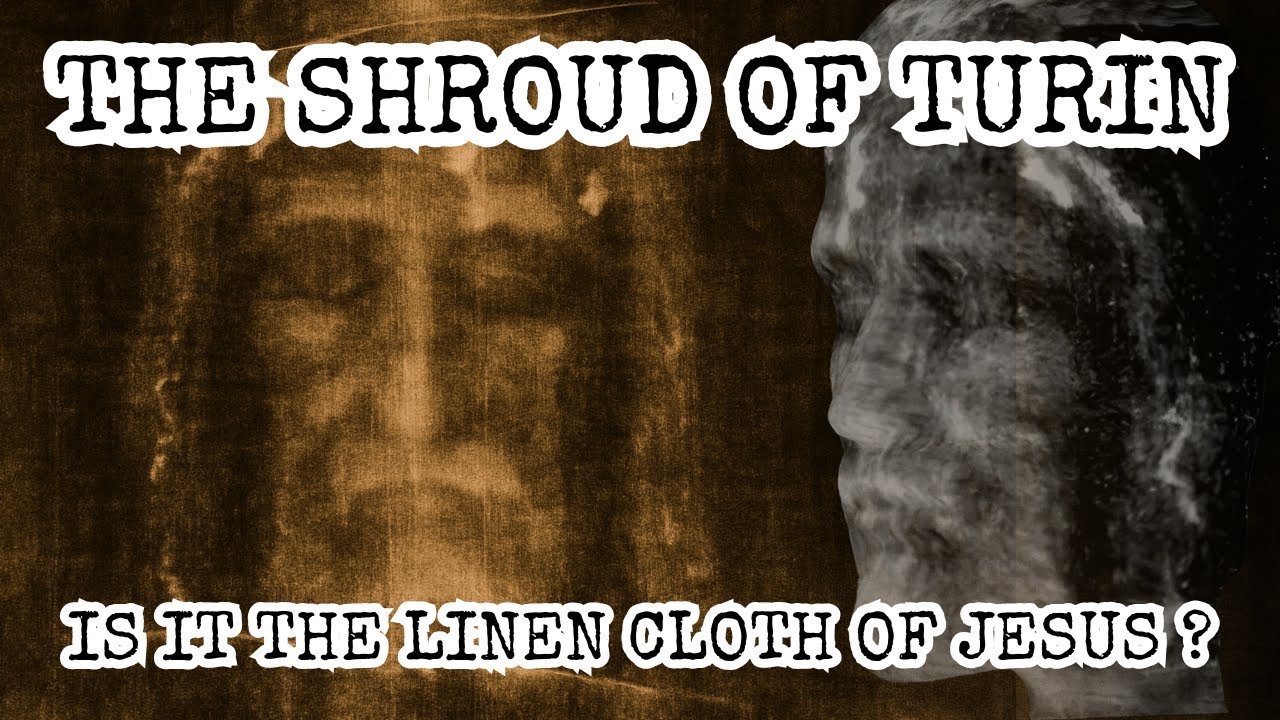

The Face in the Linen: What Science and Faith Really Say About the Shroud of Turin

For centuries, the Shroud of Turin has hovered between faith and science, reverence and controversy.

A faint, ghostly image of a man appears imprinted on the ancient linen cloth, a figure many believe to be Jesus of Nazareth, bearing wounds that seem to match the crucifixion described in the Gospels.

Now, renewed attention driven by modern imaging technology and artificial intelligence has reignited one of history’s most enduring questions: does the Shroud truly reveal the face of Jesus, or is it humanity’s most powerful religious illusion?

The linen cloth, preserved in Turin, Italy, shows the front and back image of a bearded man with long hair, visible wounds on the wrists, feet, side, and head, and markings consistent with scourging.

Believers argue the anatomical accuracy is too precise, too detailed, and too symbolically aligned with biblical accounts to be coincidental.

Skeptics counter that belief has often filled the gaps where evidence remains uncertain.

What has intensified the debate is the image itself.

Unlike paintings or drawings, the Shroud’s image contains no visible brush strokes, pigments, or dyes.

Under magnification, the image appears to exist only on the outermost fibers of the cloth, as if scorched or chemically altered rather than applied.

When photographed in 1898, the photographic negative revealed startling clarity, making the image appear more lifelike in negative than positive.

This discovery stunned scientists and theologians alike and launched decades of investigation.

Supporters of authenticity point to forensic details that seem uncannily realistic.

Bloodstains appear to precede the body image, suggesting the image formed after the wounds occurred.

The blood patterns correspond to gravity-based flow from a crucified body.

The wrists, rather than the palms, are marked, aligning with what modern anatomy suggests would be required to support body weight during crucifixion.

The side wound appears consistent with a spear thrust.

To many researchers, these details are difficult to dismiss as medieval artistry.

In recent years, digital reconstruction and AI-assisted imaging have added another layer of intrigue.

Using advanced algorithms, researchers have enhanced the facial features embedded in the cloth, producing three-dimensional renderings that reveal a solemn, asymmetrical face marked by swelling and trauma.

These reconstructions have circulated widely online, reigniting claims that the Shroud offers the closest possible glimpse of what Jesus may have looked like.

Yet science has never spoken with a single voice on the Shroud.

In 1988, radiocarbon dating tests conducted by three independent laboratories concluded that the cloth dated to between 1260 and 1390 AD, placing it firmly in the medieval period.

![]()

For many skeptics, this result settled the matter.

The Shroud, they argued, was a remarkable but ultimately human-made relic.

However, critics of the carbon dating have raised serious objections.

They argue that the sample tested may have come from a repaired section of the cloth, contaminated by centuries of handling, smoke from fires, and environmental exposure.

Subsequent studies have suggested chemical inconsistencies across different areas of the Shroud, fueling claims that the dating may not represent the original linen.

No scientific experiment has yet successfully replicated the Shroud’s image formation process in full.

Attempts using paint, heat, chemicals, or photography fail to recreate the same microscopic characteristics.

The image contains three-dimensional information encoded within its shading, something no known medieval technique was capable of producing intentionally.

This does not prove a miraculous origin, but it does deepen the mystery.

The question of whether the face on the Shroud is Jesus ultimately rests on interpretation rather than proof.

There is no inscription, no signature, no historical record that conclusively links the cloth to first-century Jerusalem.

At the same time, there is no definitive explanation for how the image was formed, nor a consensus that fully accounts for all observed properties.

The Catholic Church has taken a careful position.

It does not officially declare the Shroud to be the burial cloth of Jesus, nor does it label it a forgery.

Instead, it presents the Shroud as an object of contemplation, one that invites reflection on suffering, sacrifice, and faith rather than demanding scientific certainty.

Popes have referred to it as a “mirror of the Gospel,” emphasizing its spiritual value regardless of its origin.

For believers, the face revealed in the linen is more than an image.

It is a connection across time, a silent witness to pain and redemption.

For skeptics, it is a reminder of how powerful belief can be in shaping interpretation, especially when science cannot yet provide all the answers.

Between those positions lies a vast gray area where mystery endures.

Modern technology has not solved the Shroud of Turin.

Instead, it has sharpened the questions.

The more the image is studied, the more it resists simple classification.

It is neither easily dismissed nor conclusively verified.

In an age that demands certainty, the Shroud offers something uncomfortable: ambiguity.

Whether the face in the linen belongs to Jesus of Nazareth or to an unknown man whose image became sacred through history, the impact is undeniable.

Few artifacts have inspired such sustained scrutiny, devotion, and debate.

The Shroud continues to sit at the crossroads of faith and science, daring both to explain it fully.

What the evidence ultimately says is this: the Shroud of Turin remains unexplained.

It challenges assumptions, defies replication, and continues to provoke awe and skepticism in equal measure.

And perhaps that is why, centuries later, the face in the cloth still looks back at us, asking not for belief or disbelief, but for humility in the face of what we do not yet understand.

News

A Homeless Girl, Her Loyal Dog, and the Moment Simon Cowell Became Human

Tears, Courage, and Gold: The Performance That Melted Simon Cowell’s Toughest Walls The studio lights burned bright over the…

The 11-Year-Old Prodigy Who Defied the Rules and Earned Two Golden Buzzers

History in Gold: The Child Guitarist Whose Performance Shocked Britain’s Got Talent The theater lights dimmed into a hush…

Whispers in the Spotlight: The Myths, Legends, and Power of Pearl Bailey

Pearl Bailey: The Shadowed Mystique Behind a Reign of Black Hollywood Royalty Pearl Bailey’s name has long shimmered in…

Brigitte Bardot Dies at 91 — From French Cinema’s Legendary Sex Symbol to Controversial Icon

BB’s Final Curtain: The Life, Fame and Complex Legacy of Brigitte Bardot Brigitte Bardot — a name whispered in…

Before His Death, Robert Redford Finally Confirmed the Truth About Paul Newman

Robert Redford’s Final Admission About Paul Newman Changes Everything For decades, the relationship between Robert Redford and Paul Newman…

From Shy Audition to Historic Victory: Darci Lynne’s Unstoppable AGT Journey

The Girl Who Changed AGT Forever: How Darci Lynne Went from Audition to Champion When Darci Lynne first walked…

End of content

No more pages to load