Faith in the Ruins: Why Christianity Flourished During the Dark Ages

When the Roman Empire collapsed in the West, much of Europe descended into chaos.

Roads crumbled, cities emptied, literacy collapsed, and political authority shattered into fragments ruled by warlords and shifting alliances.

To later generations, this era became known as the Dark Ages—a time defined by instability, fear, and uncertainty.

Yet amid the ruins of empire, one institution did not merely survive.

It expanded, hardened, and reshaped the continent.

Christianity, once a persecuted minority faith, became the spiritual backbone of medieval Europe.

The question that has puzzled historians for centuries is not whether Christianity endured the Dark Ages, but why it thrived.

The answer begins with fear.

In a world where life expectancy was short, disease was poorly understood, and violence could erupt without warning, people desperately sought meaning and reassurance.

Christianity offered something uniquely powerful: a coherent explanation for suffering and a promise that it was not meaningless.

Plagues were not random horrors but trials.

War was not chaos but punishment or testing.

Death was not the end but a passage.

In an age when the world seemed to be falling apart, Christianity gave people a story that made sense of the collapse.

But belief alone does not explain Christianity’s dominance.

Structure mattered just as much as faith.

As Roman political institutions vanished, the Church stepped into the vacuum.

Bishops became administrators.

Monasteries became centers of stability.

While kings rose and fell, the Church remained continuous, organized, and recognizable across borders.

It preserved Roman legal ideas, administrative habits, and even infrastructure.

In many regions, the Church was the only institution capable of coordinating relief during famine, negotiating truces, or maintaining records.

To ordinary people, Christianity was not an abstract belief system—it was the most reliable presence in their lives.

Monasteries played a critical role in this transformation.

Isolated yet disciplined, monastic communities became engines of survival.

They stored food, cared for the sick, and preserved knowledge at a time when books were rare and fragile.

Monks copied manuscripts by hand, saving not only Christian texts but also works of classical philosophy, science, and history that would otherwise have been lost forever.

Ironically, much of what we know about ancient Greece and Rome survived because medieval Christians believed knowledge itself was sacred.

Christianity also adapted rather than resisted local cultures.

When missionaries moved into pagan regions, they did not erase traditions overnight.

Instead, they reinterpreted them.

Pagan festivals became Christian holidays.

Sacred groves became church sites.

Local gods were transformed into saints, their stories reshaped but their emotional power preserved.

This strategy allowed Christianity to feel familiar rather than foreign, easing conversion without constant violence.

Faith spread not only through force, but through narrative flexibility.

Another reason Christianity flourished was its message of moral equality.

In a rigidly hierarchical world defined by birth and violence, Christianity preached that all souls were equal before God.

While this did not erase social inequality, it offered dignity to the poor, the enslaved, and the powerless.

The idea that even kings were subject to divine judgment was radical in a time when rulers often claimed absolute authority.

This moral framework gave Christianity credibility not just among peasants, but among rulers who sought legitimacy beyond brute force.

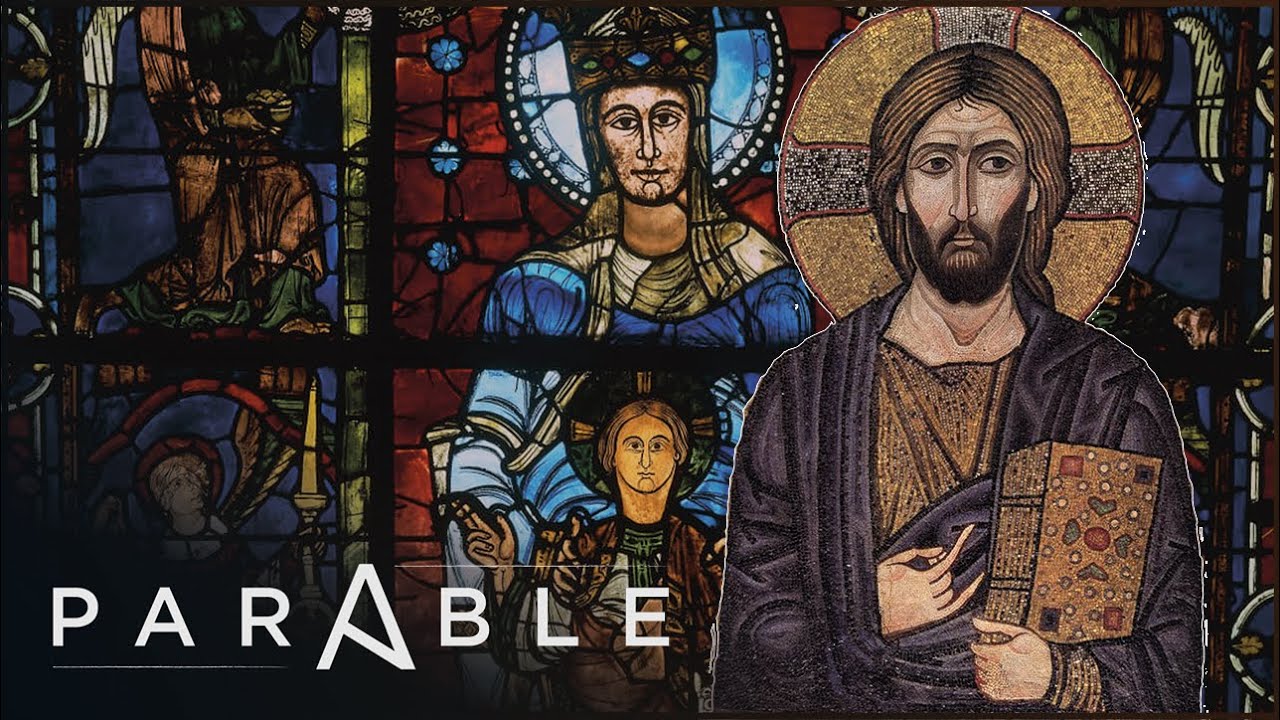

The Church also mastered symbolism and ritual.

Cathedrals rose where palaces had fallen, dominating landscapes both physically and psychologically.

Bells structured daily life.

Rituals marked birth, marriage, and death.

In a largely illiterate society, visual storytelling—stained glass, murals, processions—made Christian narratives unforgettable.

Faith was not confined to texts; it was experienced through sound, sight, and repetition.

Christianity did not rely on individual interpretation alone.

It shaped collective memory.

Crucially, Christianity offered continuity across generations.

In a world where political borders shifted constantly, the Church provided a shared identity that transcended tribes and kingdoms.

Latin, preserved by the Church, became the language of scholarship and diplomacy.

Pilgrimage routes connected distant regions.

Shared doctrine created a sense of belonging to something larger than any single kingdom.

Christianity became Europe’s cultural glue.

Critics have often accused the medieval Church of suppressing progress, yet this interpretation oversimplifies history.

The Church did restrict certain ideas, but it also funded education, preserved science, and laid the foundations for universities.

Medieval scholars were not rejecting reason; they were attempting to reconcile faith and logic.

The intellectual revival of later centuries did not emerge despite Christianity, but in many ways through it.

Christianity also benefited from timing.

It rose precisely when people needed meaning the most.

Had the Roman Empire remained stable, Christianity might have remained a minority faith.

Instead, the collapse of old systems made room for new ones.

Christianity did not just fill the void left by empire—it replaced it with something more resilient, rooted not in armies but in belief.

By the time Europe began to stabilize, Christianity was no longer simply a religion.

It was law, education, morality, art, and identity woven together.

The Dark Ages did not weaken Christianity.

They forged it.

Pressure stripped it down to its essentials, tested its institutions, and forced it to adapt or die.

It adapted.

What emerged from the darkness was not a fragile faith clinging to survival, but a powerful system that had learned how to endure collapse.

Christianity thrived during the Dark Ages because it understood something timeless: when the world breaks apart, people do not search first for power or wealth.

They search for meaning.

And Christianity was ready with an answer when everything else fell silent.

News

A Homeless Girl, Her Loyal Dog, and the Moment Simon Cowell Became Human

Tears, Courage, and Gold: The Performance That Melted Simon Cowell’s Toughest Walls The studio lights burned bright over the…

The 11-Year-Old Prodigy Who Defied the Rules and Earned Two Golden Buzzers

History in Gold: The Child Guitarist Whose Performance Shocked Britain’s Got Talent The theater lights dimmed into a hush…

Whispers in the Spotlight: The Myths, Legends, and Power of Pearl Bailey

Pearl Bailey: The Shadowed Mystique Behind a Reign of Black Hollywood Royalty Pearl Bailey’s name has long shimmered in…

Brigitte Bardot Dies at 91 — From French Cinema’s Legendary Sex Symbol to Controversial Icon

BB’s Final Curtain: The Life, Fame and Complex Legacy of Brigitte Bardot Brigitte Bardot — a name whispered in…

Before His Death, Robert Redford Finally Confirmed the Truth About Paul Newman

Robert Redford’s Final Admission About Paul Newman Changes Everything For decades, the relationship between Robert Redford and Paul Newman…

From Shy Audition to Historic Victory: Darci Lynne’s Unstoppable AGT Journey

The Girl Who Changed AGT Forever: How Darci Lynne Went from Audition to Champion When Darci Lynne first walked…

End of content

No more pages to load