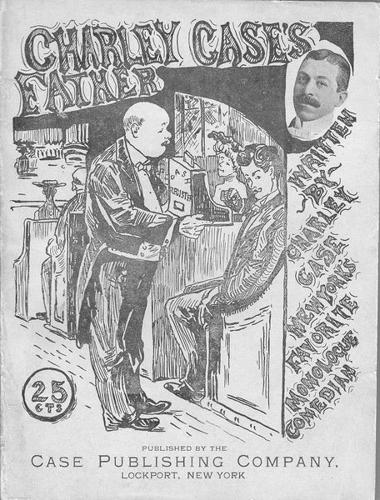

A pioneering vaudeville performer whose quiet, story-driven humor helped shape modern stand-up, Charley Case rose from 19th-century variety stages to national fame before his life ended in a sudden and mysterious tragedy.

In the long, colorful history of American comedy, certain names shine so brightly they seem to eclipse everyone else. Today, Dave Chappelle is often hailed as one of the most influential comedic voices of our time.

But decades before the term “stand-up comedy” even existed, a man named **Charley Case** was quietly shaping the art form into something we would all recognize today. His story, though fascinating and tragic, has been largely lost to time.

Born on **August 27, 1858**, Charley Case entered a world where live entertainment was dominated by vaudeville, minstrel shows, and variety acts.

He was of mixed race, a fact that carried both social obstacles and a complex place within the performance world of the late 19th century.

For many entertainers of color, the only way to gain access to the stage was through blackface performances—a practice that is rightly condemned today, but which was then a deeply entrenched part of popular culture.

Case began his career in this space, but unlike many of his peers, he soon began to strip away the paint, the exaggerated costumes, and the stock characters. He wanted to connect with audiences on a more direct, personal level.

What made Case so groundbreaking was his refusal to hide behind theatrical gimmicks. He would walk onstage alone, wearing a suit, and simply **talk**. There were no props, no elaborate backdrops—just Charley and his audience.

His humor was rooted in observation, sharp wit, and stories about everyday life. In an era when most comedic performances relied on slapstick or broad caricatures, Case’s quiet, conversational delivery was radical. Audiences didn’t just laugh; they leaned in.

He performed extensively on the vaudeville circuit, traveling to cities like Chicago, Philadelphia, and New York.

Theaters like Tony Pastor’s Opera House—often called the birthplace of vaudeville—were his stage, and his name began appearing alongside some of the biggest acts of the time. He shared bills with jugglers, singers, magicians, and even literary humorists, but his act stood apart.

Contemporary accounts suggest that his pacing was deliberate, his voice calm, drawing laughter in a way that felt almost intimate. “You could hear a pin drop until the punchline,” one theater manager recalled years later.

The term **“punchline”** itself may have been popularized in part because of Case. He had a signature habit of delivering a story with a steady rhythm, then making a quick, almost imperceptible hand gesture—a “punch” in the air—just before the comedic payoff.

This little flourish became so associated with his style that fellow performers started using the phrase “build to the punchline” when talking about their own material.

Offstage, Case was known for being a private, even melancholy figure. Despite his skill at making strangers laugh, friends described him as introspective and easily unsettled.

By **1910**, his mental health had deteriorated to the point where he suffered what was then called a “nervous breakdown.”

Seeking a change of scenery, he traveled to England for a tour. It was there that he performed a satirical song about temperance and prohibition—a piece that would later inspire W\.C. Fields’ 1933 short film *The Fatal Glass of Beer*.

Audiences abroad found his dry, understated delivery both refreshing and surprising; one British reviewer described him as “a man who tells the truth and somehow makes it funny.”

Case returned to the United States and continued to perform, but the pressures of touring and the unpredictable nature of show business weighed heavily on him. By the fall of **1916**, he was living in New York City with his wife, Charlotte.

Friends noticed he seemed unusually withdrawn. On the morning of **November 26, 1916**, tragedy struck. According to reports, Case was in his room cleaning a revolver when it discharged, striking him fatally.

While the official explanation was that it was an accident, those close to him suspected suicide. Witnesses claimed his last words were a polite, almost absurdly composed “Pardon me” before collapsing.

The shock was compounded when Charlotte, upon hearing the news of her husband’s death, is said to have suffered a heart attack and died shortly afterward.

The couple’s sudden passing sent ripples through the vaudeville community. Many performers—some of whom had shared stages with him for decades—expressed grief that the man who had inspired them to seek more personal, truthful comedy was gone.

Despite his impact, Charley Case’s name quickly faded from public memory. Vaudeville itself would be overtaken by radio, film, and eventually television, and newer comedic stars emerged to claim the spotlight.

Yet his fingerprints remain all over modern stand-up. His commitment to performing without artifice, speaking directly to the audience, and building stories toward a single, devastating laugh became the foundation on which countless comedians would stand.

Decades later, scholars of comedy began to rediscover his work through old playbills, newspaper clippings, and the recollections of surviving vaudevillians.

One modern historian referred to him as “the missing link between 19th-century variety acts and 20th-century stand-up.” Dave Chappelle, Richard Pryor, George Carlin—all in their own ways—owe something to the path Case cleared.

Today, remembering Charley Case is more than an exercise in nostalgia; it’s a reminder that every art form has its unsung architects.

His story tells us that innovation often comes quietly, without fanfare, from people who are simply trying to make an honest connection. It also reminds us that the people who make us laugh the hardest are sometimes the ones who carry the heaviest burdens.

In a cultural moment when comedy is again grappling with its purpose—whether to provoke, to comfort, or to challenge—Case’s philosophy still resonates. His life may have ended abruptly over a century ago, but his belief in the power of humor to reflect truth endures.

And for anyone who has ever stood alone under the lights, facing a crowd armed with nothing but their words, Charley Case’s spirit is still there, in every well-timed pause and every perfectly delivered punchline.

News

Bobby Whitlock, Co-Founder of Derek and the Dominos, Passes Away at 77 After Battle With Cancer

Bobby Whitlock, co-founder of the iconic blues-rock band Derek and the Dominos and longtime collaborator with Eric Clapton, has died…

Michael Jordan’s Boat Hooks \$400K Prize After Dramatic 71-Pound White Marlin Haul at White Marlin Open

Michael Jordan’s boat scores a stunning \$400,000 second-place prize after landing a massive 71-pound white marlin at the fiercely competitive…

South Florida Pierogi Maker Pledges Free Dumplings for Life to Alan Dershowitz After Martha’s Vineyard Snub

Former Trump lawyer Alan Dershowitz claims he was denied service over his politics at a Martha’s Vineyard farmers market, sparking…

Decomposing Body Found Near Florida Highway Confirms Tragic End for Missing Teen Giovanni Pelletier, Raising New Questions

A decomposing body found near a Florida highway confirms the tragic death of 18-year-old Giovanni Pelletier, who vanished after a…

Emma Thompson Reveals Donald Trump Asked Her on a Date the Same Day She Got Divorced — “I Thought It Was a Joke”

Emma Thompson reveals the surprising story of how Donald Trump asked her out on a date the very day she…

David Justice Opens Up About His Short-Lived Marriage to Halle Berry: “Is This the Woman I Want to Have Kids With?”

David Justice opens up about the challenges and cultural clashes that led to his short marriage with Halle Berry, revealing…

End of content

No more pages to load