In a world where famine, disease, and war plagued daily life, Europeans sought an explanation for their suffering—and many believed they found it in the form of witches. Fueled by religious zeal, superstition, and political ambition, the hunt for the Devil’s servants became a frenzy that crossed borders and generations. From quiet villages to royal courts, no one was safe from suspicion.

Dateline: Alps-to-Rhine Corridor, 1428–1489 — The European witch hunts did not explode out of nowhere.

They began as a series of anxious local crackdowns in the 1400s, hardened into policy by a papal decree in 1484, and then metastasized when a brutal handbook rolled off late-medieval presses a few years later.

By the end of the century, magistrates from the Valais Alps to the German Rhineland had the same playbook, the same vocabulary of fear, and the same procedures for extracting confessions—fuel for the continent-spanning frenzy that would claim tens of thousands of lives in the 16th and 17th centuries.

The fuse was lit in the high valleys of the western Alps.

In August 1428, delegates from seven districts in the Valais (today straddling Swiss and French territory) demanded investigations into “sorcerers,” initiating what historians now recognize as the first systematic witch-hunt in Europe.

Within months, ad hoc commissions formed, lists of suspects circulated, and interrogations began.

A clerk might push a quill toward a bound villager and say, “Name your accomplices,” while a notary tallied every neighbor mentioned—each name a future arrest.

The campaign continued into the 1430s and 1440s, establishing a template: community rumor became “evidence,” coerced testimony became a map, and the map became mass prosecution.

Even as the Alpine trials unfolded, scholars were reframing sorcery in theological terms that made new panics thinkable.

Around 1435–1437, the Dominican theologian Johannes Nider wrote *Formicarius*, a treatise that shifted the image of the magic-worker from an educated male ritualist to an unlearned, mostly female conspirator in league with demons.

He also popularized a then-novel idea—the witches’ sabbath—where adherents gathered at night to renounce the faith and receive powers from the Devil.

Nider’s pages were not court verdicts, but they gave judges a conceptual net: if witchcraft was a demonic sect, then every accused person had co-conspirators, rites, and a chain of command. “Confess the meeting place,” an examiner could insist, “and the names you saw there.”

By the late 1450s, the panic had migrated onto the plains of northern France. In Arras, 1459–1460, a cluster of arrests spiraled into the *Vauderie d’Arras*, a full-blown “sect” case.

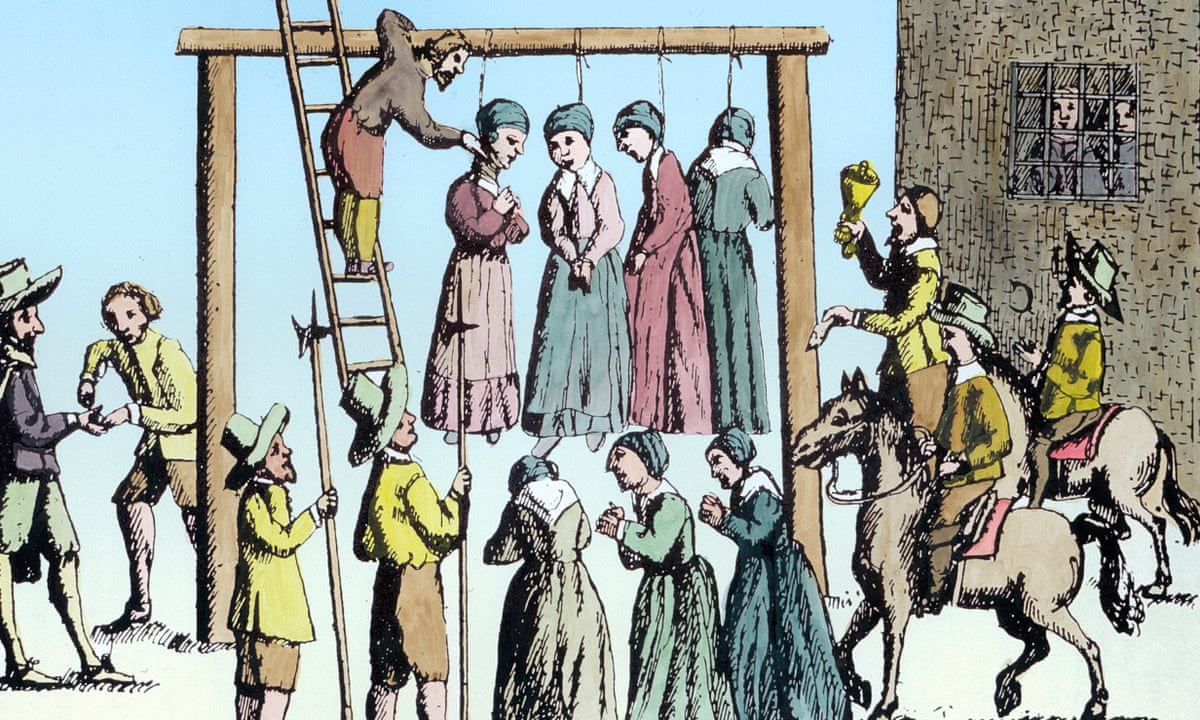

Chroniclers left unusually rich documentation: nobles, clerics, and townspeople alike were swept up; confessions under torture conjured images of night rides and infernal assemblies; burnings followed.

The scandal rattled Burgundy so deeply that some victims were posthumously exonerated decades later—too late to save the dead, early enough to show that political winds mattered as much as theology.

“Recant and you may live,” interrogators allegedly promised; “name others and you will be spared.” Most were not spared.

If local panics supplied the kindling, an official decree supplied the match. On December 5, 1484, Pope Innocent VIII issued *Summis desiderantes affectibus*, a papal bull that explicitly recognized witchcraft as a real and pressing danger in parts of the Holy Roman Empire and authorized inquisitors—by name, Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger—to pursue cases in regions where bishops had obstructed them.

The document did not invent witch hunting, but it handed anxious magistrates a permission slip stamped with Rome’s authority.

The bull’s message to princes, bishops, and city councils read like marching orders: cooperation was expected; obstruction would be punished. In chancelleries from Cologne to Trier, scribes copied the Latin, and officials nodded: “We have our mandate.”

Then came the handbook that standardized everything. In 1486–1487, Heinrich Kramer—Latinized as Henricus Institoris—published the *Malleus Maleficarum* (“Hammer of Witches”) in Speyer.

Part demonology, part criminal-procedure manual, it taught authorities how to identify, interrogate, and convict alleged witches, weaving misogyny into jurisprudence and recommending torture to secure confessions.

Kramer even prefaced a later edition with the papal bull to bolster his authority. Printers, newly empowered by Gutenberg’s technology, moved copies across the Rhine corridor and beyond; the same headings and the same “tests” began popping up in scattered jurisdictions.

“Search the body for the Devil’s mark,” one section advised; “trust no tears.” As the book spread, so did a uniform prosecutorial imagination.

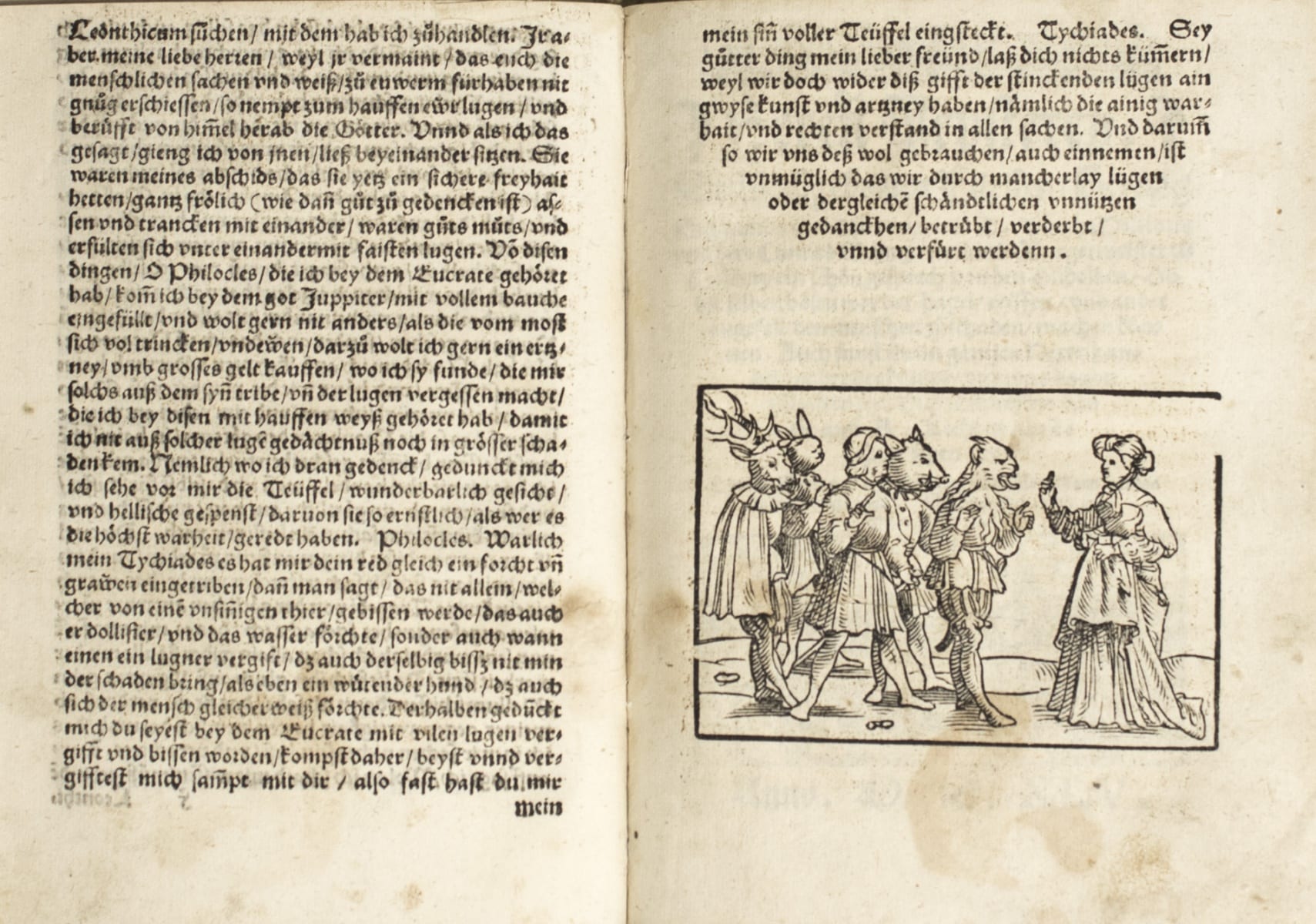

The ripple effects were immediate. Within a few years, other visual and textual works amplified the new orthodoxy.

In 1489, jurist Ulrich Molitor’s *De Lamiis et Pythonicis Mulieribus* appeared with vivid woodcuts: women flying on beasts, kissing demons, boiling infants—images that gave magistrates and parishioners a shared picture of what they were supposed to fear.

If Nider had supplied a theory and Kramer a manual, Molitor supplied the storyboard.

A village elder pointing to a pamphlet woodcut could whisper, “This is what they do,” and a courtroom would see not a quarrelsome neighbor but a member of a murderous sect.

All of this collided with the politics and hardships of the late 1400s. Famine shocks, disease flare-ups, and border wars made misfortune feel intentional.

The older church text known as the *Canon Episcopi*—once skeptical that “night flights” were anything but delusion—was eclipsed by new authorities who insisted the flights were real and punishable.

The legal and religious transition was stark: where earlier clerics had urged pastors to correct wayward imaginations, later jurists and theologians urged judges to correct the body with rope and fire. “Illusion became evidence,” one historian quips; in the records, it became indictment.

The bureaucratic mechanics hardened next. In towns that adopted inquisitorial procedure, a single coerced confession could launch a cascade. Accused people were asked the same leading questions, their answers compared, and “concordances” tallied.

Lists of names became arrest warrants; inventories of household goods preceded forfeitures; and tithes of seized property bonded local elites to the process.

Even where Rome’s courts did not preside, the new ideology seeped into secular law. By 1563 in Scotland and 1563/1604 in England, statutes made witchcraft a capital offense in Protestant realms as well, proving the “sect” theory had long outgrown its Catholic roots.

But that was the next act. The first act—the beginning—was Alpine and Burgundian panic, papal authorization, a printed manual, and the hum of presses churning fear into formula.

Read the early interrogations and you hear the rhythm of what would become Europe’s witch-trial century. A notary in Valais: “Do you renounce the Devil?” A defendant, exhausted:

“I saw nothing.” The examiner, consulting a rubric: “Name the women who rode with you.” In Arras: “Where did you gather?” “On the meadow beyond the mill,” a man sobs, “and there we feasted.”

Whether such words were spoken exactly so is less important than the structure that forced them—the leading questions, the torture that made denial a prelude to confession, and the vision of a continent-wide conspiracy that made every village quarrel look like a demonic plot.

By 1489 the pieces were in place. Local panics had pioneered methods; theologians had defined a heretical “sect”; a papal bull had welded divine sanction to secular muscle; and the *Malleus* had supplied a portable, duplicable procedure.

In the decades to come, climate shocks of the “Little Ice Age,” religious civil wars, and intensifying state power would turn that procedure into a continent-wide machine.

But the story of how it began is narrower and eerily modern: a few early crises, a moralized narrative, a bureaucratic toolkit, and a media technology that could scale both.

The first sparks fell in the Alps and Flanders; the wind that carried them was Latin on parchment and ink on paper. When the flames finally roared, Europe had already stacked the wood.

News

CBS Will Not Celebrate Tenth Anniversary of Stephen Colbert’s ‘Late Show’ as Accusations Persist He Was Canceled to Appease Trump

CBS is keeping quiet as Stephen Colbert’s Late Show approaches its tenth anniversary, leaving fans and insiders questioning why a…

Fox News’ Bret Baier ticketed for distracted driving amid Trump DC crackdown: ‘Didn’t know there was paparazzi’

Fox News anchor Bret Baier found himself on the wrong side of the law this past Saturday, pulled over for…

Stealing Our Culture Again — Mediocre White Men Take Credit While Black Creators Stay Invisible

In a heated podcast interview, Joy Reid accused “mediocre white men” of repeatedly stealing cultural achievements from Black and Brown…

Spilled Drink, Brutal Attack — Woman Knocked Out in Vicious Rose Bowl Concert Beating

What should have been a night of music and celebration at the Rose Bowl turned into a nightmare when a…

“Christmas Joy Turned to Panic” — Was JonBenét’s Death a Household Accident Disguised as a Brutal Murder?

It began with a frantic 911 call, a chilling ransom note, and a family in panic—yet within hours, the case…

Jillian Michaels Shakes Up the Fitness World: A Bold New Chapter Beyond Weight Loss

When Jillian Michaels first stormed onto screens in “The Biggest Loser,” she embodied the no-excuses, results-driven era of early 2000s…

End of content

No more pages to load