The global population has reached 8.1 billion in 2025, but fears of overpopulation are giving way to hope, as many countries experience falling birth rates and rising living standards.

In 2025, humanity stands at a pivotal point in its history. The global population has surged to an estimated 8.1 billion, more than four times what it was just a century ago. In 1800, Earth was home to only 1.8 billion people.

That number climbed steadily—2.3 billion by 1940, 3.7 billion in 1970, and 7.4 billion in 2016. Now, less than a decade later, the world has added nearly 700 million more people.

This unprecedented growth has sparked fear, fascination, and debate.

Will cities crumble under the weight of expanding populations? Will climate change, food insecurity, and water shortages push us toward global instability? Or—against all odds—could this be the gateway to a new age of human progress?

For most of the 20th century, overpopulation was viewed as a global crisis in the making. In the 1960s, booming birth rates led scientists and policymakers to predict a bleak future: famines, wars, and mass poverty.

These concerns weren’t unfounded. Urban slums mushroomed, millions faced hunger, and entire regions struggled to keep up with soaring population demands.

But a quiet revolution was happening underneath the chaos—one that is now changing the trajectory of the human story.

“It’s not just about how many people are born,” said a leading demographer in New York, “it’s about how people choose to live—and how much better we’ve become at helping them live well.”

What looked like a crisis was, in fact, part of a well-documented pattern: the demographic transition—a four-stage process that nearly every country on Earth is experiencing, albeit at different speeds.

In the early 18th century, even the wealthiest regions were plagued by poor sanitation, disease, and high infant mortality. Most families had many children, but few lived to adulthood. Population growth was minimal. Then came the Industrial Revolution, which changed everything.

Britain led the way in industrialization. With technological innovation came better healthcare, nutrition, and infrastructure. Cities modernized. Sanitation improved.

Women gained more access to education and work. Slowly, death rates fell—but birth rates remained high, leading to a temporary population explosion.

From 1750 to 1850, Britain’s population doubled. But eventually, as families no longer needed to “replace” lost children, they began to have fewer kids. Birth rates fell. Society shifted. The population growth slowed—and eventually stabilized. That was the fourth stage.

This pattern once took centuries to unfold. But in the modern era, developing countries are moving through the stages much faster.

Take Bangladesh, for example. In 1971, the average woman there had 7 children, and child mortality was devastatingly high. By 2025, the fertility rate has dropped to 1.9, and childhood survival rates have dramatically improved.

In just over 50 years, the country went from being a case study in overpopulation to a model of demographic transition.

Even more striking is Iran, which underwent one of the fastest fertility transitions in history—dropping from more than 6 children per woman in the 1980s to under 2 in just a decade.

Why the rapid shift? Access to modern healthcare, education—especially for girls—and family planning tools played a huge role. And while each country’s path is unique, the direction is consistent.

Globally, the average fertility rate in 2025 stands at 2.3 children per woman, down from 5.0 in the 1970s. And yet the population continues to grow. Why?

Demographers call it population momentum. The people born during the peak years of population growth—the 1980s and 1990s—are now adults and having children. Even if they’re having fewer kids, the base population is larger. But this momentum won’t last forever.

The United Nations’ latest projections, updated in 2022, suggest that the global population will peak around 10.4 billion in the 2080s and then begin to decline by the end of the century. Not because of catastrophe—but because of choice.

And this choice is already reshaping our world.

More people than ever are living longer, healthier lives. Extreme poverty rates have fallen, literacy has risen, and education—especially for women and girls—has become more widespread.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the region still experiencing the fastest growth, countries like Ethiopia and Kenya are already seeing significant declines in fertility and improvements in child survival.

“When you invest in children and in women,” said a development expert in Nairobi, “you don’t just reduce birth rates—you unleash a wave of social and economic transformation.”

Some nations, like Japan, South Korea, and Italy, are now grappling with the opposite problem: population decline. Birth rates there have fallen so low that governments are offering financial incentives to encourage couples to have more children.

The demographic conversation is shifting—from too many people to too few.

And that’s the paradox of the population boom: it’s ending. Not with a bang—but with a slow, steady evolution toward balance.

So what does the future hold?

It’s still uncertain. Climate change, inequality, and migration will continue to challenge global systems. But the fear that the planet will collapse under its own population weight is no longer supported by data.

Instead, we’re entering a new phase—one defined not by growth, but by opportunity.

More people entering the middle class. More innovation, ideas, and collaboration. And if the momentum continues, the nations once seen as needing aid will become the world’s engines of progress.

The global population explosion, once viewed as a threat to civilization, is now a story of transformation—a story that, in 2025, still has many chapters left to write.

Because the question was never just “How many people?”

It was always: What kind of world will they help build?

News

Shocking Revelations from Last Survivor of Admiral Byrd’s Expedition: Secrets Beneath the Antarctic Ice!

At 99 years old, Robert Johnson, the last survivor of Admiral Byrd’s 1946 Antarctic expedition, has come forward with shocking…

Did Archaeologist Eilat Mazar Uncover King David’s Lost Palace? Shocking Revelations from Jerusalem!

Renowned archaeologist Dr. Eilat Mazar claimed to have uncovered the remains of King David’s palace in Jerusalem, challenging long-standing debates…

Titanic’s Dark Secret: Ballard’s Confession Reveals the Truth Behind the Tragedy

Oceanographer Robert Ballard, who discovered the Titanic wreck, reveals new findings suggesting the disaster was caused by design flaws and…

GOOD BOY SAVES GRANDMA! Florida Dog Named Eeyore Becomes a Hero After Guiding Deputy to Fallen 86-Year-Old

The 86-year-old woman was out walking her son’s dog when she fell, according to authorities Destin, Florida —…

NASA MISSED IT! Asteroid Skims Just 300 Miles from Earth — Closer Than the Space Station

A 9.8-foot asteroid named 2025 TF passed just 265 miles above Earth — closer than the International Space Station —…

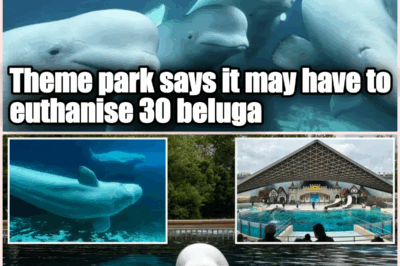

Theme park says it may have to euthanise 30 beluga whales unless it is allowed to export them to China

Marineland, a Canadian theme park near Niagara Falls, has warned it may euthanize 30 beluga whales after the government denied…

End of content

No more pages to load