Dr. Darla McFaren did not expect to freeze mid‑sip of her coffee. Yet when she unfolded the sepia‑toned photograph on her Yale University desk that crisp October morning, she thought: This is no ordinary find.

The image showed three girls, ages perhaps 13 to 15, standing in front of weathered wooden houses. Their clothes were ragged, their postures uneven—but what held Darla’s eye was their faces.

One wore a tentative smile, another a mournful frown, and the third a sly, mischievous grin. Yet beneath their varied expressions there lay something unexpected: relief—as if they had just survived something terrible.

“Olivia,” she called to her graduate assistant, “come see this.”

Olivia Martinez, whose expertise in early 20th‑century American photography had already proved invaluable, hurried over. She leaned gently over Darla’s shoulder, eyes narrowing.

“The clothing suggests extreme poverty,” she said, “but look at how they hold themselves. There’s no shame. No collapse.”

Darla nodded. “Exactly. And this technique—see the paper, the developing concentric rings? This is not from the Depression era.” She flipped the photo and her finger traced a faint, weathered timestamp: 1913. No full date, no city—just the solitary year.

For the rest of the morning, Darla and Olivia pored over every detail. In a faint corner, a nearly illegible studio mark flickered under magnification.

The houses behind the girls looked like rural American architecture from the early 1900s: wide porches, simple siding, a dirt path weaving in front. It felt remote, perhaps somewhere in the Midwest or the Old West.

“We should go to Professor Foster,” Darla finally declared.

Two days later, Darla and Olivia sat with Professor James Foster, Yale’s authority on American social history between 1900 and 1920. On his oak desk lay the photograph, surrounded by magnifiers, books, and archival notes.

He examined the girls’ postures, their setting, and their expressions.

After a long moment, he murmured, “Fascinating. All the clues point toward reform institutions or industrial schools of the era.

But something’s off. These girls don’t look institutionalized. They look free.”

Olivia leaned forward. “You think they escaped?”

Foster nodded slowly. “It’s possible. The scandals around such institutions—neglect, forced labor, abuse—are well documented.

Some children fled. But if this photo was taken after their escape, that changes everything.”

Over the following weeks, the trio plunged into their mystery. They contacted historical societies in Kansas, Nebraska, Missouri. They hired a digital forensics expert to enhance the faint studio mark.

Meanwhile, Olivia posted the image on a history forum. The responses trickled in—until a phone call changed everything.

Mrs. Mattie Sullivan, an 89‑year‑old retired librarian from Brownell, Kansas, responded. “My grandmother always told of three girls who appeared here around 1913 or ’14,” she said, voice quavering.

“They looked like they’d endured hell—but they smiled as though they’d won something.”

Darla gripped the phone. “Do you recall anything else?”

“Oh, yes,” Mrs. Sullivan whispered. “They claimed to have walked nearly 50 miles from the Berthmore Industrial School for Girls in Terracotta. That place was infamous—children sent there for minor faults. My grandmother said the town protected them.”

Thanks to Mrs. Sullivan’s memories, Darla traced records of the Berthmore Industrial School for Girls, which operated from 1898 to 1917 in northwestern Kansas.

After a state investigation revealed widespread abuse, it was shuttered. Many girls tried to run—but most were forcibly returned. These three, however, vanished from the records.

The more Darla and Olivia dug, the stranger the case became. Mrs. Sullivan revealed that after arriving in Brownell, the three girls were sheltered by townspeople, adopted into homes, raised quietly.

One became a teacher, another a nurse, the third opened a bakery. Their stories, once whispered, were never recorded—until now.

Then the phone rang again. It was Detective Michael Torres, from the Kansas City / Missouri cold case unit. “Dr. McFaren, I’ve been following your research,” he said.

“We’ve found documents about two girls missing from a wealthy Nebraska family in April 1913. The dates match your photograph almost exactly.”

Darla’s blood ran cold. Torres told of the Whitmore sisters, Ruth (13) and Catherine (15), daughters of a prominent banking magnate. Their disappearance was quietly reported.

The mystery deepened when the descriptions and even facial features matched two of the girls in the Brownell photograph—except here, they were dressed in rags, not finery.

Torres slid a journal across the table: it belonged to Catherine Whitmore. In delicate handwriting she described a household of abuse, strict oppression, and fear.

She confided that she and Ruth disguised themselves as orphans, left the home, and walked miles to freedom. Mary—the third girl—was a servant and friend who aided their escape with dresses and cover stories.

“It was a brilliant ruse,” Torres said. “No one looked for them as wealthy girls. The public believed these were institutional escapees. Their real story stayed hidden.”

Darla felt tears sting her eyes. The faces in the photograph—relief, pride, defiance—were no accident. These girls had escaped a gilded cage. They traded wealth and security for freedom and anonymity.

The next month, Darla, Olivia, and Foster published their findings in the Journal of American Historical Photography. The once‑anonymous photograph was now emblematic: a record of courage, disguise, and survival.

The image now hangs in the Brownell Historical Society, with a placard: “Three Girls, One True Story: Freedom Over Submission.”

Dr. McFaren keeps a framed copy on her desk—a daily reminder that sometimes truth is not what it seems, and that even the most ordinary photo can hold a profound secret.

News

Is This the Final Clue? New Expedition Zeroes In on Amelia Earhart’s Long-Lost Plane Wreckage in Remote Pacific Lagoon

An international research team is preparing to investigate a mysterious underwater object in Nikumaroro Lagoon that could be the wreckage…

Experts Discover Old Photo of 3 Friends From 1899…Then Zoom in and Are Left Speechless

When Dr. John Thorne first opened the battered cedar box at the back of the Denver Heritage Auction House, he…

5,000-Year-Old Egyptian Map of America Uncovered: A Discovery That Could Rewrite History!

The basalt slab, found in a sealed tomb at Sakara, matches modern satellite data of American geography and is made…

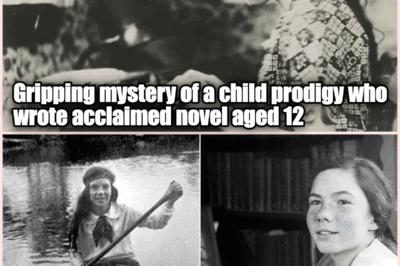

The Enigmatic Disappearance of Child Prodigy Barbara Newhall Follett: A Literary Genius Who Vanished Without a Trace

Barbara Newhall Follett, a celebrated child prodigy who published her first novel at the age of 12, mysteriously vanished at…

Meghan Markle Faces Backlash for Controversial Instagram Video in Princess Diana’s Shadow

The video, showing Markle casually resting her feet while smiling and chatting, has sparked outrage among royal watchers and reignited…

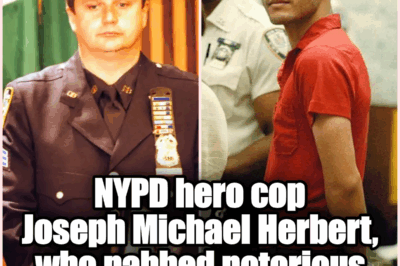

NYPD Legend Who Took Down the ‘New York Zodiac Killer’ Dead at 68 — City Mourns a True Hero

Retired NYPD Detective Joseph Michael Herbert, famed for capturing the notorious “New York Zodiac Killer,” has died at age 68….

End of content

No more pages to load