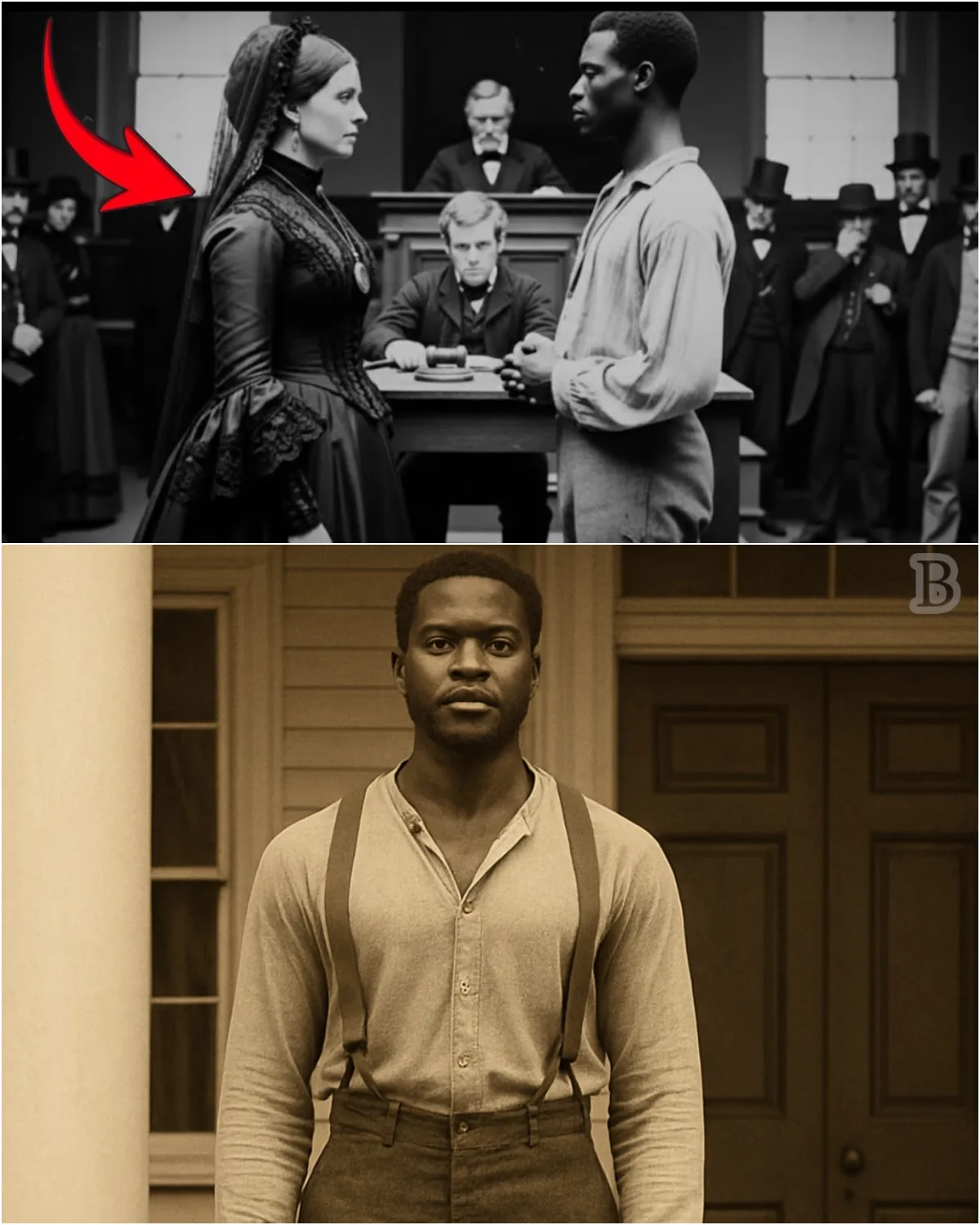

The Montgomery auction yard was thick with heat that August morning in 1847.

The sun pressed down like a punishment, and the smell of sweat, tobacco, and fear drifted under the wooden awning.

Buyers fanned themselves with newspapers, murmuring over cotton prices and the endless war with boll weevils.

It was an ordinary auction day — until he stepped onto the block.

The man was enormous.

Six feet three, shoulders like a barn door, back broad as the river. His skin shone with health, no whip scars, no sign of sickness. His name, they said, was Isaac. The crowd drew a collective breath.

A specimen, someone whispered.

Worth fifteen hundred, maybe more.

But no one lifted a paddle.

The auctioneer tried.

“Strong field hand, prime age, no illnesses — who’ll start at one thousand?”

Silence.

Even the flies stopped buzzing.

“Eight hundred?”

A murmur.

“Six hundred?”

Men shifted backward. Boots scraped the dust. Nobody spoke. Finally the auctioneer’s voice cracked.

“Four hundred?”

Still, no hands.

And then a planter with tobacco-stained teeth cupped his hands around his mouth and shouted across the crowd:

“You’d have to be mad to buy that one!”

Laughter rippled uneasily, though nothing was funny. Eyes darted toward Isaac. He did not flinch. His expression was unreadable — not savage, not angry, simply watching.

From the back of the crowd, a woman stepped forward.

Charlotte Whitfield, widow for three years, managing her late husband’s plantation alone. She was thirty-two, skin pale beneath a wide straw hat, dress black though the mourning period had long since ended. People said she should remarry. People said a woman had no business running land. People said many things Charlotte had learned to ignore.

She raised her hand.

“I’ll bid five hundred.”

The courtyard fell silent.

The auctioneer stared, as if waiting for the joke to finish. When it did not, his mallet came down with a dull crack.

“Sold.”

Charlotte stepped forward. As she walked, an elderly planter — Colonel James Sutton — reached out and caught her wrist with surprisingly strong fingers.

“Charlotte,” he hissed, eyes darting. “That ain’t a bargain. That’s a death wish.”

She lifted her chin. “I need workers. He looks strong.”

Sutton’s voice dropped to a rasp.

“He’s killed four masters in five years. Four. One died with his neck broke like a chicken. One drowned in a creek with hands that weren’t his own. Two simply vanished. Bodies found later. You don’t want that man on your land.”

Charlotte looked at the auction block. Isaac still stood there, alone. Not chained. Not held. Simply waiting, as though he knew fear had bought him freedom many times.

She pried her hand loose. “He’s mine now.”

Sutton shook his head. “No, girl. You’re his.”

The journey back to her plantation was quiet. Isaac walked behind the wagon, ropes loosely tied — though no one pulled them. He never tried to run. He watched the trees, the sky, the dust. Charlotte watched him in the small square of her rear-view mirror.

When they reached Whitfield Plantation, the overseer, Travis Monroe, came storming from the barn.

“What in God’s name is that?” he demanded.

“A new hand,” Charlotte said. “You’ll put him with the field crew.”

Travis swore, spit, and shook his head. “We don’t need a damn giant. We need obedient workers.”

Charlotte’s eyes went cold.

“Obedience is not what we’re buying, Mr. Monroe. Labor is.”

Isaac carried his own belongings to the cabin assigned to him — though he owned nothing. That evening, he ate his supper alone. The other enslaved people watched him cautiously but without hostility. Word traveled before he arrived.

Some whispered he was cursed.

Some whispered he was blessed.

Some whispered he was the Devil’s son.

Others whispered he was God’s retribution.

In the dark, Charlotte stood on the veranda and watched the moon rise over the cotton fields. She had remodeled her plantation for survival: rotating crops, allowing Sunday rest, refusing to whip. But profit was thin. She needed strength in the fields.

She needed someone like Isaac.

But she could not stop hearing Sutton’s voice.

He’s killed four masters.

For weeks, Isaac worked silently. He lifted more, dug deeper, plowed longer than any man she had ever seen. He never complained. He never broke tools. He never raised his voice. The overseers avoided him, as if proximity itself was dangerous.

Charlotte noticed something else.

When Isaac passed the row where children worked, they watched him with curiosity, not fear. He sometimes paused to straighten a crooked fence post or lift a heavy basket from a boy’s shoulders. He spoke rarely, but his voice was low and gentle.

One evening after harvest, Charlotte found him repairing the plantation’s broken water wheel, using only muscle and rope.

“You could have asked for help,” she said.

Isaac didn’t look up. “Help makes noise.”

“You don’t like noise?”

“No reason to draw attention.”

She hesitated. “Is it true?” she asked quietly. “What they said about you?”

Isaac straightened. His eyes were dark as river water.

“They died,” he said. “That is true.”

“Did you kill them?”

He returned to his work. “Depends what you mean.”

Charlotte felt a chill. “It seems a simple question.”

“No,” he said. “It isn’t.”

Curiosity became unease. Unease became fascination.

The plantation changed. No tools went missing. No fights broke out. The overseer grew resentful.

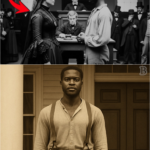

One afternoon Travis challenged Isaac.

“You think you’re better than the rest of ’em?” he sneered.

Isaac turned slowly. “I think I’m me. That’s all.”

Travis swung his whip.

Isaac caught it.

The leather snapped tight between them. No one spoke. Even the cicadas held their breath.

Travis went white.

Isaac let go.

“Don’t do that again,” he said softly.

The overseer walked away shaking.

Word spread faster than wind.

Children said Isaac could catch lightning.

Old women said he was born under an eclipse.

Men said if he wanted freedom, no gate could hold him.

Some nights Charlotte wondered the same.

Why hadn’t he run?

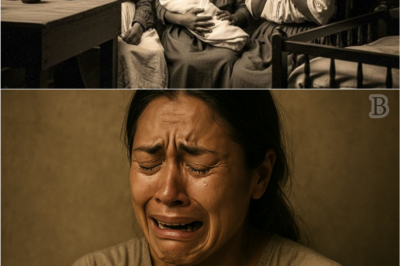

Then came the storm.

Rain hammered the fields. Lightning split a tree near the quarters. The roof of a cabin caught fire. People screamed and scrambled for water.

Out of the darkness, Isaac appeared.

He lifted beams, threw buckets, carried two children from the flames. When the storm passed, the cabin was blackened but standing. No one had died.

Charlotte found him later, sitting alone in the mud, drenched, exhausted.

“You saved them,” she said.

He shook his head. “Fire would have killed them. Fire has already taken too much here.”

She sat beside him, skirts soaking in the mud.

“Tell me,” she whispered. “The four masters. How did they die?”

Isaac stared at the ruined cabin.

“They died of fear,” he said. “One feared losing his property. One feared losing his power. One feared losing his life. One feared the truth.”

“And you?”

He turned to her.

“I never laid a hand on them. But fear kills fast. Fear does the work.”

Charlotte’s heart beat hard.

“Do you fear me?” she asked.

Isaac’s gaze softened.

“No,” he said. “You are the first who sees me.”

The moon broke through the clouds. Smoke rose faintly from the cabin. Somewhere, a child cried in his sleep, then quieted.

Charlotte exhaled.

She finally understood.

Isaac had not killed four masters.

They had killed themselves — on the blade of their own terror.

Fear was the weapon.

He was only the mirror.

Years later, when the war came, when whispers of freedom rolled like thunder from the North, Isaac stood beside Charlotte on the porch.

“Storm’s coming,” he said.

“Yes,” she answered. “And we will weather it.”

The children they had saved ran through the yard. The cotton fields shimmered with heat. History was changing.

People would tell stories about Isaac for generations — giant, killer, saint, devil, guardian.

All of them true, and none of them true.

He had only ever been one thing:

A man no one dared to own.

News

Bloodlines in the Dust

Spring came early to Natchez in 1859. The river swelled with brown water and the magnolias were already blooming when…

The Brides of Father Hayes

The Saint of Saint Bridget’s In 1968, the West Side parish of Saint Bridget’s was the kind of place where…

The Midwife’s Deadly Secret: Babies That Never Died

The rain came down in sheets so thick the world outside the window barely existed. It drummed against the warped…

They Laughed When the Giant Cowboy Picked the Amish Girl— But Out on His Remote Ranch, She Discovered Why He Needed Her More Than Anyone Knew

Hannah first heard the sheriff’s decree before the sun was even up. “Get up this instant.” Her mother’s voice cracked…

A Christmas at the Wrong Station

Christmas Eve, 1885. Snow fell in slow, heavy flakes over the empty train platform. The wind cut through Grace Whitlow’s…

The Ranch Hands Laughed When They Sent the “Fat Girl” to Calm His Wild Stallion…

Nora Hale had never been the kind of woman people looked at twice. Not in the small town of Dusty…

End of content

No more pages to load