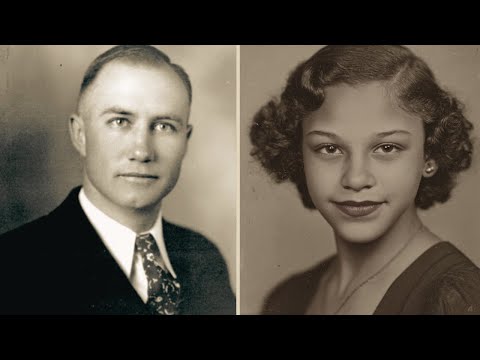

For half a century, Strom Thurmond stood in the bright, unforgiving light of American politics — a U.S.

Senator, a presidential candidate, and one of the loudest voices defending segregation in the South.

He filibustered civil rights bills for 24 straight hours, fought school integration, and condemned interracial marriage as a threat to the “Southern way of life.”

He was the public face of white supremacy.

And yet, in the shadows of that carefully crafted image, there was a secret that would not die.

Her name was Essie Mae.

In South Carolina, 1925, the world was divided by law and by habit.

Black and white lived in separate neighborhoods, used separate schools, separate fountains, separate doors.

Anti-miscegenation laws didn’t just discourage interracial relationships — they criminalized them.

In the Thurmond household of Edgefield, the color line was as rigid as anywhere else.

The family was prominent, respectable, white.

John William Thurmond was an attorney and politician.

His son, James Strom Thurmond, 22 years old, was athletic, educated, ambitious.

He had all the advantages a young white man could have in the deep South.

And then there was Carry Butler.

She was 15.

Black.

Small, quiet, careful.

She cleaned the Thurmond home, washed their clothes, served their meals.

She lived under their roof, but never as an equal.

In that time, in that place, a young Black maid working for a powerful white family did not have real choices.

She did what she was told.

She understood the unspoken rules: be useful, be invisible, be silent.

Somewhere in that year, Strom and Carry crossed a line that could never be spoken aloud.

He was 22, she was barely 15.

He was the son of the house; she was the help.

He had freedom; she had none.

Whatever words were exchanged, whatever moments passed between them, the imbalance of power was absolute.

In that South, consent was a word the law reserved for white men and white women.

For a Black teenage servant girl, “no” was not truly an option.

Carry became pregnant.

In 1925, such a pregnancy was more than scandal — it was a threat.

Not for Strom, but for her.

The law might look away when a white man took a Black girl, but the shame always fell on her, never on him.

The solution was swift and cruel.

Carry was sent away before the pregnancy showed.

Hidden with relatives in another county, far from prying eyes.

There, in October 1925, she gave birth to a baby girl: Essie Mae.

The baby’s skin was light, her features unmistakable.

Anyone who looked closely would see the Thurmond face echoed in her tiny features.

But in the South of 1925, no one dared say that out loud.

When Essie Mae was six months old, another decision was made — perhaps by Carry, perhaps for her.

The baby was sent north to Pennsylvania to live with Carry’s sister, Mary, and her husband, John Henry Washington.

The North promised distance, anonymity, a chance to grow without constantly reflecting the shame of a powerful white man.

Essie Mae grew up in Coatesville, Pennsylvania, believing Mary and John Henry were her parents.

She went to school, played with friends, lived the life of a working-class Black girl in an industrial town.

She knew nothing of South Carolina.

Nothing of the Thurmonds.

Nothing of the man whose blood she carried.

Meanwhile, Strom Thurmond’s life unfolded along a very different path.

He became a teacher, then a lawyer, then a rising political star.

His name gathered weight.

His ambitions sharpened.

Nowhere in his public story was there any mention of Carry Butler, or the baby girl shipped quietly north.

Secrets in the South rarely died.

They were buried.

In 1938, when Essie Mae was thirteen, her world cracked.

Her “father” left.

Her “parents” divorced.

Confusion settled over the house like dust.

No one explained.

No one invited questions.

In that family, less curiosity meant less pain.

Then one summer, a tall, elegant woman arrived from the South.

“This is your Aunt Carry,” Mary said.

Essie was fascinated.

There was something magnetic about this woman — in the way she walked, the way she spoke, the way Essie couldn’t help but follow her around the house.

She felt a pull she couldn’t name, a connection that didn’t fit the story she’d been told.

One day, hidden in the hallway, Essie heard her own name in whispered conversation.

She heard Carry’s tears.

She heard Mary say, “It’s time.

That night, Mary sat her down.

The truth landed like a blow: Mary was not her mother.

Carry was.

The aunt was the mother; the mother was the aunt.

Thirteen years of certainty dissolved in a few sentences.

Essie’s mind spun.

She looked at Carry with new eyes — saw in her face something that looked like home.

A thousand questions flooded in, but one swallowed all the others:

“If Carry is my mother… who is my father?”

Carry’s answer was a name Essie did not know: Strom Thurmond.

A white man.A lawyer.A rising politician in South Carolina.

A man who could never recognize her publicly, because he was white, she was Black, and the South would never forgive him.

Essie carried that secret like a stone in her chest for three years.

In 1941, Carry fell ill.

Not gravely, but enough to bring Essie south for the first time, back to the soil where she was born.

She was sixteen.

For the first time, she walked the roads of South Carolina, felt the heat, saw the segregated signs, breathed the air of the place that had shaped both her mother and her father — and then tried to pretend she didn’t exist.

Carry had been waiting for this moment.

Quietly, carefully, she arranged a meeting.

Not at the Thurmond home.

Not in public.

But in a white, one-story law office with a sign out front:

Thurmond & Thurmond, Attorneys at Law.

Essie assumed her father must be a driver, a clerk, someone working behind the scenes.

She did not expect the man in the sharp suit behind the big desk.

Strom Thurmond was thirty-eight, tall, composed, every inch the Southern gentleman lawyer.

He looked at Carry first.

Then at Essie.

His gaze lingered on her face — her skin tone, her eyes, the shape of her jaw.

It was like watching a man confront his own reflection in a distorted mirror.

“You have a beautiful daughter,” he said to Carry at last.

Essie froze.

Carry turned to her and spoke the words she had waited sixteen years to hear:

“Essie Mae, this is your father.

”

No embrace.

No tears.

No apologies.

The conversation that followed was stiff, careful — about history, education, the state seal, anything but the sixteen years of silence between them.

It felt less like a reunion and more like a legal appointment.

When it ended, Essie left with one undeniable truth: he was her father… but not yet her dad.

That uneasy, secretive distance would define their relationship for the next sixty-two years.

As Essie matured, Strom’s career exploded.

He became governor of South Carolina.

Then, in 1948, the face of the Dixiecrats — the States’ Rights Party that broke from the Democrats to protest civil rights reforms.

He ran for president on a platform of segregation, proclaiming the purity of the white race, the dangers of interracial mixing, the right of states to keep Black and white apart.

Crowds cheered as he promised to defend their “Southern heritage.

None of them knew he had a Black daughter whose college education he quietly paid for.

While Strom thundered against integration, Essie studied at South Carolina State College, a historically Black institution barely a hundred miles away.

He visited campus in his governor’s limousine, met her in offices and courtyards, slipped her folded bills, asked about her classes.

Students saw.

They suspected.

But in that time, in that place, some truths were too dangerous to speak aloud.

Later, as a U.S.

Senator, he spoke for 24 hours straight against a modest civil rights bill designed to protect Black voting rights.

Newspapers hailed his stamina.

Segregationists celebrated his courage.

While he spoke, Essie was living as a Black woman in America — raising children, working in schools, facing the daily realities of the very discrimination he fought to preserve.

She tried, from time to time, to talk to him about it.

About segregated bathrooms.

About unequal schools.

About the laws that pressed on her life and the lives of her children.

He deflected.

Changed the subject.

He would be her provider, sometimes a presence, but never her public defender.

He loved his daughter in secret.

In public, he fought her people.

Strom Thurmond served in the Senate until he was one hundred years old.

Fifty years in Washington.

A lifetime in the spotlight.

He died in 2003, honored with long obituaries that described his “complicated legacy,” his “evolution” from fiery segregationist to more moderate elder statesman.

They listed his four white children.

They did not mention Essie Mae.

For seventy-eight years, she had kept his secret — out of loyalty, confusion, perhaps a daughter’s complicated love for a father who could never fully step into the light with her.

But secrets have weight, and she was tired of carrying his alone.

Six months after his death, at seventy-eight years old, Essie Mae Washington-Williams held a press conference.

Calm, dignified, she sat in front of a wall of cameras and quietly told the truth.

Her mother was Carry Butler, a Black maid.

Her father was Strom Thurmond, the legendary segregationist senator.

She had the documents.

The records.

The checks.

The witnesses.

The story.

The country erupted.

Two days later, the Thurmond family issued a statement confirming her claim.

They acknowledged her as his daughter and welcomed her as family.

In 2004, South Carolina carved her name into the stone of his monument at the state capitol, beside the children he had claimed in life.

At last, the shadow stepped into the sunlight.

Essie Mae went on to write her memoir, Dear Senator, recounting a life lived in the space between shame and recognition, love and betrayal, silence and truth.

She never fully resolved the contradiction of her father — the man who helped her in private while harming her community in public.

But in the end, she chose not revenge, but clarity.

Not scandal, but dignity.

She died in 2013, remembered not just as a teacher and author, but as the daughter who finally forced history to tell the whole story.

News

🌴 Population Shift Shakes the Golden State: What California’s Migration Numbers Are Signaling

📉 Hundreds of Thousands Depart: The Debate Growing Around California’s Changing Population California has long stood as a symbol…

🌴 Where Champions Recharge: The Design and Details Behind a Golf Icon’s Private Retreat

🏌️ Inside the Gates: A Look at the Precision, Privacy, and Power of Tiger Woods’ Jupiter Island Estate On…

⚠️ A 155-Year Chapter Shifts: Business Decision Ignites Questions About Minnesota’s Future

🌎 Jobs, Growth, and Identity: Why One Company’s Move Is Stirring Big Reactions For more than a century and…

🐍 Nature Fights Back: Florida’s Unusual Predator Plan Sparks New Wildlife Debate

🌿 From Mocked to Monitored: The Controversial Strategy Targeting Invasive Snakes Florida’s battle with invasive wildlife has produced many…

🔍 Ancient Symbols, Modern Tech: What 3D Imaging Is Uncovering Beneath History’s Oldest Monument

⏳ Before the Pyramids: Advanced Scans Expose Hidden Features of a Prehistoric Mystery High on a windswept hill in…

🕳️ Secrets Beneath the Rock: Camera Probe Inside Alcatraz Tunnel Sparks Chilling Questions

🎥 Into the Forbidden Passage: What a Camera Found Under Alcatraz Is Fueling Intense Debate Alcatraz Island has…

End of content

No more pages to load