Jefferson’s Hidden Family: The Story America Tried to Bury

In September 1802, readers in Richmond, Virginia, unfolded their newspapers and found a story that felt like a small earthquake.

A journalist claimed that the president of the United States, Thomas Jefferson, the man who had written the words “all men are created equal,” was keeping one of his enslaved women as his concubine.

Her name, he wrote, was Sally.

The article said she lived at Monticello.

It said she had several children.

It said those children looked suspiciously like the president.

The country exploded with gossip and outrage.

Jefferson’s enemies used the scandal as a weapon.

Newspapers printed obscene cartoons, preachers thundered from their pulpits, and polite society whispered behind closed doors.

The president himself said nothing.

He did not deny it.

He did not admit it.

He did what powerful men have done for centuries when confronted with uncomfortable truths: he stayed silent and waited for time to bury the noise.

But even that infamous newspaper article did not tell the whole story.

It never mentioned the detail that turned a scandal into something far darker.

Sally Hemings was not only enslaved by Jefferson.

She was also the half-sister of his dead wife.

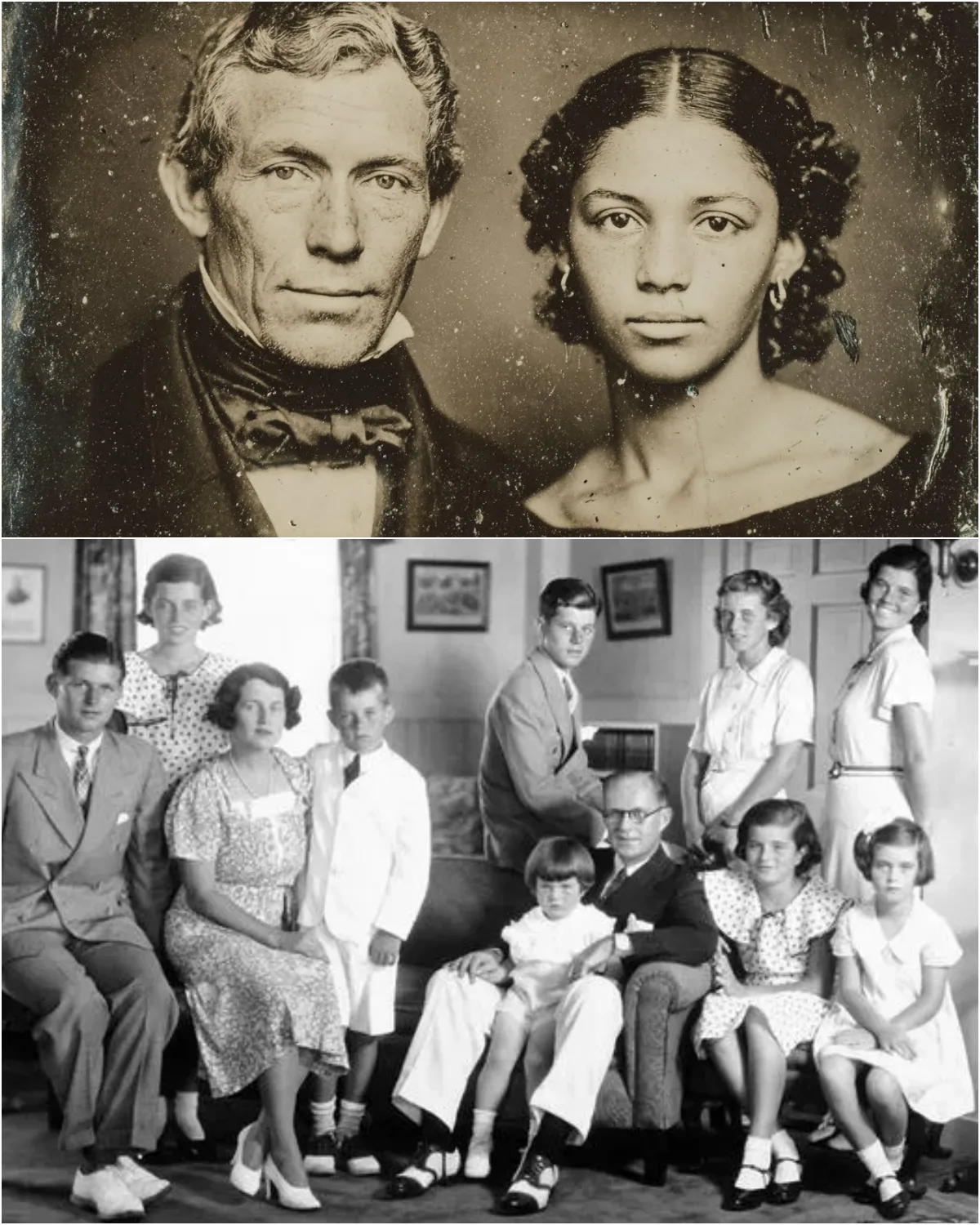

In 1782, Thomas Jefferson was 39 years old.

He was already a well-known lawyer, a philosopher, an architect, and the author of the Declaration of Independence.

He owned a large plantation in Virginia called Monticello, worked by over a hundred enslaved people.

That same year, his wife Martha died after giving birth to their sixth child.

Her death shattered him.

For three weeks, Jefferson shut himself in his room, refusing to see anyone.

When he finally emerged, he made a vow: he would never remarry.

No woman, he said, would ever replace Martha.

He kept that promise.

But he found another way not to be alone.

Martha had brought a large dowry into the marriage: land, money, and enslaved people.

Among them was the Hemings family, led by a woman named Elizabeth Hemings.

Elizabeth had twelve children.

Six of them, including one little girl named Sally, were believed to be the children of Martha’s own father, John Wayles.

That meant something twisted and cruel:

Martha Jefferson, the mistress of Monticello, and Sally Hemings, the enslaved girl in her house, were half-sisters.

When Martha died, Jefferson inherited the Hemings family along with the furniture and livestock.

Sally was only nine years old—thin, light-skinned, with long straight hair and delicate features.

She did not look like the African field hands who worked under the sun.

She looked like the white family who owned her, because she was part of that family by blood.

Instead of being sent to the fields, Sally was assigned to the main house.

She helped in the kitchen, served at the table, cleaned rooms, and attended to Jefferson’s daughters.

That alone set her apart.

Most enslaved children her age were already laboring outside.

But the Hemings children were different: they were the secret, half-recognized shadow of the white Wayles line.

To the outside world, they were property.

Inside Monticello, they were something much more complicated.

As the years passed, Jefferson’s world moved beyond Virginia.

In 1784, he sailed to France as a diplomat for the new American republic.

He took his eldest daughter, Patsy, with him and left his younger daughters with relatives, planning to send for them later.

After several years in Paris, Jefferson decided it was time to bring his nine-year-old daughter Polly to live with him.

He wrote to his relatives in Virginia, asking that the girl be sent across the Atlantic with a responsible female companion—someone older who could care for a child during a dangerous six-week sea voyage.

When the ship arrived in London in June 1787, the captain wrote a letter to Jefferson explaining a change of plans.

The woman who was supposed to accompany Polly had fallen ill at the last moment.

Instead, the family had sent a substitute: a fourteen-year-old enslaved girl from Monticello named Sally Hemings.

Jefferson received the letter, arranged for Polly and Sally to travel from London to Paris, and did not openly complain.

That silence would become a pattern.

For Sally, the journey was like falling off the edge of her world.

She had never left Virginia.

She had never seen a great city.

Now she stood in Paris, surrounded by buildings, crowds, markets, and fashions she had no words for.

And waiting for her there was a man she had known since childhood—her owner, her dead half-sister’s husband, Thomas Jefferson.

He had last seen her as a nine-year-old girl.

Now she was fourteen.

Taller.

More graceful.

Her features had sharpened into a face that reminded him of someone he had loved and lost.

She looked like Martha.

Jefferson decided that Sally would stay in Paris as part of his household.

She helped look after Polly and Patsy, learned French, and received training in sewing and proper European service.

For two years she lived in a city where, unlike in Virginia, slavery was not legally recognized.

In France, the law said something extraordinary:

an enslaved person could claim their freedom just by asking.

On paper, Sally was free.

She could have gone to a court.

She could have refused to return to Virginia.

She could have stayed in a country where no one could legally force her back into chains.

But she was sixteen.

She was alone in a foreign land.

She did not speak the language fluently.

She had no money, no friends, no family except the Jeffersons.

The difference between “free in theory” and “free in reality” was the difference between a door unlocked and a door you are too afraid to open.

Somewhere between 1787 and 1789, in that Parisian house, a relationship began—if “relationship” is even the right word for what happens between a powerful, middle-aged master and a teenage girl who is, in practice, dependent on him for everything.

He was forty-four.

She was sixteen.

He had power.

She had none.

Consent, in a situation like that, becomes a slippery, fragile word.

Then, in 1789, Jefferson received an invitation that would change both their lives.

George Washington wanted him to serve as secretary of state in the new American government.

Jefferson would have to leave France, return to the United States, and restart his life in Virginia and the new capital.

He arranged passage home.

He bought tickets for his daughters, for Sally’s brother James, and for Sally herself.

But when Sally learned of the plan, she refused to go.

By then she was about three months pregnant.

The father was Thomas Jefferson.

In France, her child would be born free.

In Virginia, the baby would be born a slave.

According to the later testimony of her son Madison Hemings, Sally told Jefferson she would stay in France, where she and her child could be free.

For once, the law was on her side.

In Paris, Jefferson could not simply force her onto a ship and send her home like a piece of luggage.

So he did the only thing he could: he negotiated.

He promised her that if she returned to Virginia, she would be treated gently.

She would never work in the fields.

She would have privileges.

Most importantly, he promised that all of her children would be freed when they turned twenty-one.

He offered her freedom—but only through her children, and only in the future.

For a frightened sixteen-year-old girl, pregnant and alone in a foreign country, those promises may have felt like the only solid ground she had.

She agreed.

In October 1789, Sally Hemings boarded a ship bound for Virginia with Jefferson and his daughters, carrying in her body the child of the man who owned her.

When Sally returned to Monticello in 1789, she was five months pregnant.

No one in the white family asked questions, at least not out loud.

The enslaved people did not need to ask; they had eyes.

In 1790, she gave birth to her first child.

The baby died within weeks.

There is almost no record of its life—just a brief, cold note in Jefferson’s papers.

Over the years that followed, more children were born.

Some died in infancy, as so many enslaved children did.

Others lived and grew, working not in the fields, but in the house, as carpenters, musicians, and attendants.

They were light-skinned—so light that many could pass for white.

Their faces echoed their father’s: the shape of the nose, the tilt of the eyes, the line of the jaw.

Everyone at Monticello saw the resemblance.

No one in power spoke of it.

In 1801, Jefferson became president of the United States.

While he served in Washington, he regularly returned to Monticello, spending long stretches of time in the house where Sally lived in a small room close to his own.

His children with her grew up in the strange half-light between two worlds—legally enslaved, socially favored, publicly unacknowledged.

Then, in 1802, the secret finally slipped into print.

James Callender, a journalist who had once supported Jefferson but later turned against him, published an article accusing the president of keeping an enslaved concubine named Sally and fathering children with her.

The story described the situation with surprising precision: the name, the location, the children, their likeness to Jefferson.

The reaction was immediate.

Jefferson’s political enemies seized the story, painting him as a hypocrite who preached equality while owning—and sleeping with—slaves.

Cartoons depicted him in grotesque caricature.

Poems mocked his morals.

Clergymen condemned his sin.

His white daughters defended him passionately, insisting that the light-skinned children at Monticello must belong to other male relatives.

They painted Callender as a liar driven by revenge.

Jefferson himself said nothing.

He did not issue a statement.

He did not sue for libel.

He did not stand up and say, “This is false,” or, “This is true.

” He simply absorbed the storm and let history move on.

Eventually, the scandal faded from the front pages.

Jefferson was re-elected in 1804.

He completed two full terms as president.

He continued to go back to Monticello.

He continued to see Sally.

Their children continued to live under his roof, half-hidden, half-protected.

There was no apology.

There was no acknowledgement.

There was only the quiet continuation of a life built on inequality.

When Jefferson finally retired from politics in 1809, he returned to Monticello for good.

He was an old man by then, sixty-six years old, burdened with massive debts and a fading plantation economy.

Sally was in her mid-thirties.

She had spent most of her life in his orbit, and she was still legally his property.

Jefferson’s finances grew worse.

He knew that when he died, Monticello would likely be sold and many of its enslaved people auctioned off.

But he still had one legal power: in his will, he could choose to free some of them.

He chose five.

Out of more than a hundred men, women, and children he owned near the end of his life, Jefferson decided to grant freedom to only five people.

Two were Sally’s brothers.

Three were Sally’s sons: Beverly, Madison, and Eston.

It was, in a narrow and incomplete way, the fulfillment of the promise he had made in Paris decades earlier.

Sally’s name, however, did not appear in his will.

After thirty-seven years as his concubine, after bearing him six children and raising four to adulthood, after living in a room next to his for decades, she remained legally enslaved when he died on July 4, 1826—the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

The nation mourned Jefferson as a hero.

Newspapers praised his genius, his vision, his service to the republic.

They wrote about his ideas, his achievements, his friendship and rivalry with John Adams, who died the same day.

They did not mention Sally Hemings.

They did not mention the children he owned.

They chose the story they wanted: the philosopher of liberty, not the man who kept a family in chains.

After Jefferson’s death, his white daughter Martha quietly allowed Sally to leave Monticello.

Without an official document, without a legal declaration, Sally simply stopped being treated as property.

She moved to nearby Charlottesville and lived with her sons Madison and Eston.

For the first time in her life, she was free in practice, if not fully in law.

The children of Sally Hemings, now technically free men and women, faced a choice about who they would be in a country obsessed with race.

They were light-skinned enough to pass as white.

They also carried the blood of both Africa and one of the most famous white men in America.

Beverly left Monticello in 1822, even before Jefferson died.

He disappeared into the North, married a white woman, and lived out his life as a white man.

His descendants would grow up unaware of their African ancestry—and unaware, in most cases, that their ancestor had been born enslaved on Jefferson’s plantation.

Harriet, Sally’s daughter, also left in 1822.

Jefferson gave her money for her journey.

She went to Washington, D.

C.

, married a white man, and passed as white until her death.

To protect her children from prejudice, she locked her true story behind her teeth and never opened it.

Madison chose differently.

He lived openly as a Black man, married a free Black woman, and stayed in the Black community.

In 1873, decades after his mother’s death, he gave an interview to a newspaper.

In it, he told everything: that his father was Thomas Jefferson, that his mother had been Jefferson’s enslaved concubine, that the promise of freedom for her children had been made in Paris and kept, if only partially.

Eston, the youngest, moved to Ohio, took the surname “Jefferson,” and at first lived publicly as a man of mixed race.

Later, he moved again, and his family began passing as white.

They kept the connection to Thomas Jefferson but let the Hemings name—and the memory of slavery—fade from the story.

In different ways, all of Sally’s surviving children tried to build lives beyond the shadow of the plantation.

Some did it by embracing their full identity.

Others did it by hiding part of themselves forever.

DNA, a Confession from the Future

For more than 150 years, Jefferson’s white descendants and many historians denied Madison’s testimony.

They insisted that Jefferson’s nephews must have fathered the Hemings children.

They called enslaved witnesses unreliable.

They clung to the image of Jefferson as a man of pure principle, uncomfortable with the idea that he had used his power over the body and life of an enslaved girl.

Then, in 1998, science stepped in.

Researchers tested the Y-chromosome DNA of male-line descendants of the Jefferson family and male-line descendants of Eston Hemings.

The match was clear.

The Hemings line carried Jefferson DNA.

There was no longer any serious doubt: a man from the Jefferson male line had fathered Eston.

Given who was living at Monticello at the time of Eston’s conception, the conclusion was almost unavoidable: Thomas Jefferson himself.

In 2000, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, which manages Monticello as a museum, finally recognized officially what enslaved people at Monticello had known, what Madison had said, and what the DNA had confirmed.

They acknowledged the relationship between Jefferson and Sally Hemings and the existence of their children.

Exhibits were updated.

Tours changed.

The small room near Jefferson’s bedroom—where Sally likely slept—became part of the story.

For the first time, the house itself began to tell a fuller truth.

The tale of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings is not a simple morality play.

It is a knot of contradictions: love and coercion, family and ownership, promises and betrayals, silence and survival.

Jefferson died celebrated as a founding father, the poet of liberty.

Sally died as a woman who had lived most of her life enslaved, recorded in one census as “white,” her existence barely mentioned in official histories.

Their children carried the weight of both names and no name at all.

Some chose Blackness and truth.

Others chose whiteness and safety.

All of them moved through a country that preferred the myth of Jefferson the hero to the reality of Jefferson the master who owned his own children.

In the end, the story that began in a Paris house and a Virginia plantation is about more than a secret relationship.

It is about the gap between the words “all men are created equal” and the world in which those words were written.

It is about what happens when power is coated in ideals and buried under respectability.

For nearly two hundred years, America turned away from Sally Hemings.

It took a son’s courage, a scientist’s test, and a museum’s reluctant honesty to finally turn her name into part of the national story.

The mystery that remains is not just what happened between a president and an enslaved girl.

It is this:

Why did it take us so long to admit that the founding of a free nation was built, in part, on the unfree lives of people like her?

News

🚨 Night-Fall Footage From a Hog-Control Operation in Texas Revealed Something NO ONE Saw Coming… And Officials Are Struggling to Explain It 😰📹🌾

😱 Texas’s Wild Hog Eradication Cameras Just Captured the Aftermath — And What Crews Found in the Trees Left Everyone…

🚨 Viral Photo Sparks Chaos: 40-Year-Old Kenyan Man Says He’s Musk’s Son… But The AI Flaws Tell a MUCH Darker Story 😰📸⚡

😱 A Kenyan Man Just Claimed He’s Elon Musk’s Secret Firstborn — And The Internet’s Reaction Exposed Something FAR More…

🚨 BREAKING: Amelia Earhart’s Plane Has Been Located After 88 Years — And The Eerie Discovery Onboard Changes EVERYTHING 😰✈️💔

😱 After 88 Years, Amelia Earhart’s Plane Was FINALLY Discovered — And What Investigators Found Inside Left the World Speechless…

👀 Hidden Cameras in the Florida Swamps Just Exposed the ONE Thing Experts Hoped Wasn’t Real… And It Changes Everything Forever 🌲😨

😱 Florida Swamp Cameras Finally Caught Something Moving in the Dark — And The Truth Is More Terrifying Than Anyone…

🔥 Navy Officials Break Their Silence: The 2025 Revelation About the USS Scorpion Is Darker, Deeper, and More Devastating Than All Theories Combined 🚢💀

😱 The USS Scorpion Mystery Was Finally Solved in 2025 — And the Truth Beneath the Atlantic Is More Terrifying…

✈️💥 Police Storm Tupac’s “Untouchable” Private Jet — What They Uncovered Feels Like a Final Message From Beyond the Grave 😳🕶️

🚨 Cops RAID Tupac’s Secret Jet — And the SHOCKING Discovery Inside Is Turning Hollywood Upside Down 😱✈️🔥 The…

End of content

No more pages to load