The morning light streamed softly through the tall windows of the Boston Historical Society’s conservation lab as Sarah Mitchell adjusted her gloves and leaned over an aging photograph.

She had spent years restoring Victorian-era images—faces frozen in stiff poses, families arranged with careful symmetry, emotions muted by long exposure times.

Most photographs told quiet, predictable stories.

This one did not.

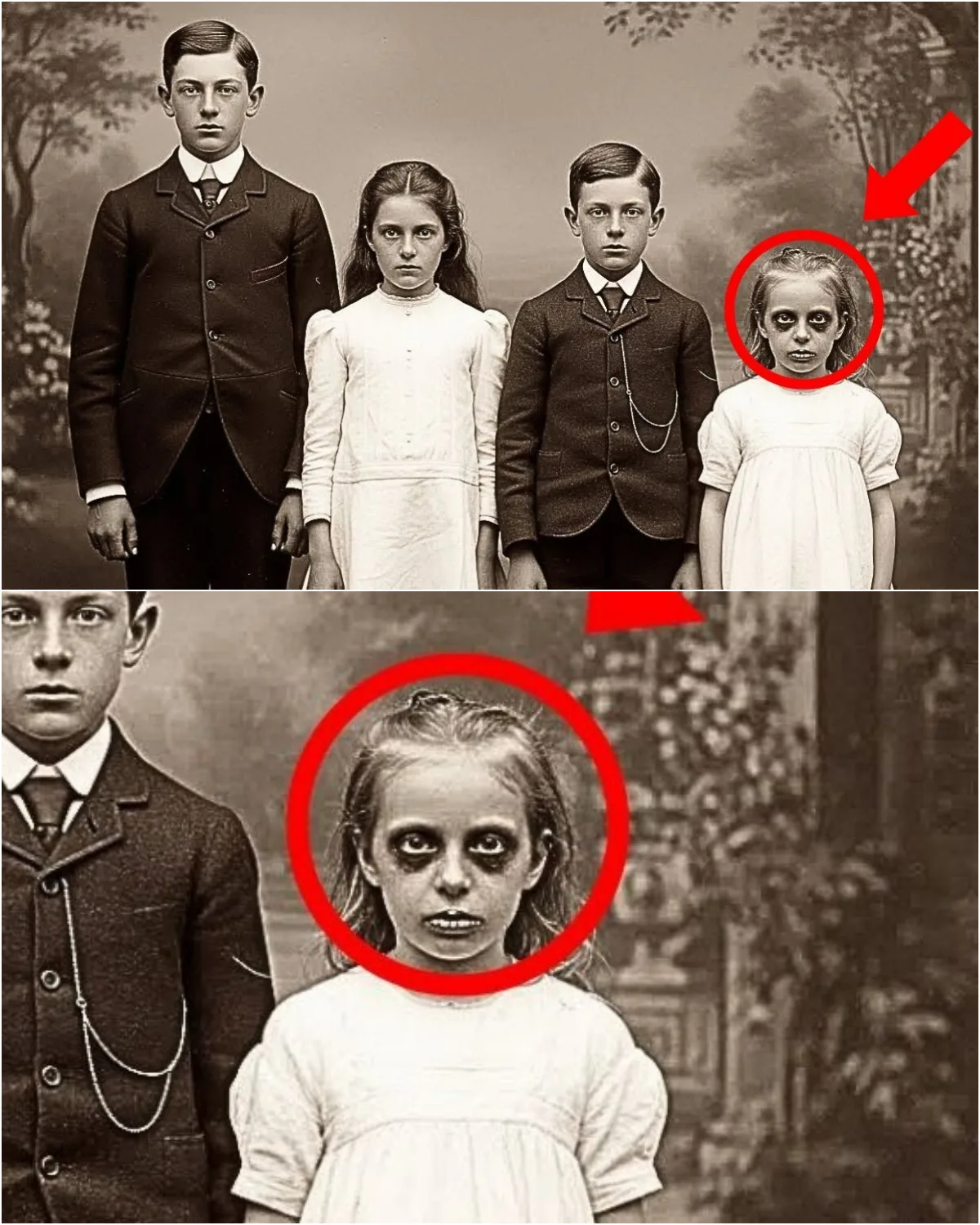

The image showed four siblings standing before a painted garden backdrop.

Their clothes were immaculate, their posture disciplined, their expressions solemn in the way children of the 19th century were taught to be.

On the back, written in faded ink, were the words: “The Patterson Children, Salem, Massachusetts, June 1887.

”

At first glance, it was ordinary.

But Sarah had learned to trust the unease that crept in when something was wrong.

As she scanned the photograph at high resolution, she zoomed in on the children’s faces.

The three older siblings looked healthy, if uncomfortable.

But the youngest—a small girl of about seven—made Sarah’s breath catch.

Her skin appeared unnaturally pale, almost translucent.

Dark shadows pooled beneath her eyes.

Her lips reflected light with a strange metallic sheen.

And her gaze… it wasn’t simply serious.

It was hollow, distant, as if she were already halfway gone.

Sarah felt a chill.

She had seen illness captured in photographs before, but this was different.

This child didn’t look tired.

She looked poisoned.

Her name, Sarah soon discovered, was Eleanor Patterson.

Five months after the photograph was taken, Eleanor was dead.

Official records listed the cause as a “digestive ailment,” a common Victorian euphemism that could mean nearly anything.

But when Sarah dug deeper—consulting medical historians, insurance archives, and court records—a horrifying pattern emerged.

Eleanor had been insured for an unusually large sum shortly before the photograph was taken.

So had another daughter years earlier.

And another.

And another.

Four little girls.

All dead between the ages of five and seven.

All insured.

All claimed by the same man.

Their father, Robert Patterson, was a struggling American merchant drowning in debt.

To the outside world, he was respectable.

Inside his home, he was something else entirely.

Medical analysis confirmed Sarah’s growing fear: Eleanor showed classic signs of chronic arsenic poisoning.

So did her sisters before her.

The poison had been administered slowly, carefully, disguised as medicine, designed to mimic natural illness.

Robert Patterson had turned his daughters into financial instruments—and then erased them from memory.

What haunted Sarah most was not only the cruelty, but the silence.

The surviving children—Henry, Margaret, and William—had lived long lives.

Yet Eleanor’s name did not appear in family records.

Neither did the names of her murdered sisters.

It was as if they had never existed.

Until now.

Sarah traced the family line to a living descendant, Jennifer Patterson, an elderly woman who loved genealogy and believed she knew her family’s past.

When Sarah gently showed her the photograph and spoke Eleanor’s name, Jennifer went pale.

“I’ve never heard of her,” she whispered.

Together, they uncovered a locked diary belonging to Margaret Patterson, the sister who stood protectively beside Eleanor in the photograph.

Margaret had known.

She had watched her sister grow weaker.

She had noticed the “special meals” prepared only by their father.

She had found white powder in his desk drawer.

And she had been slapped into silence.

Margaret carried the truth for the rest of her life.

So did her mother, Clara Patterson, who had tried—desperately—to stop her husband.

Court records revealed she had feared for her life and the lives of her remaining children.

In an era when women’s voices were dismissed, Clara had been trapped.

When she finally escaped, she did so broken, burdened by guilt, and haunted by the daughters she could not save.

Years later, Robert Patterson died with high levels of arsenic in his system.

History never proved who administered it.

But Margaret’s diary offered one final, chilling line: “Some men deserve the fate they receive.

”

Sarah realized the photograph was never meant to be art.

It was documentation.

Possibly taken for insurance purposes.

It captured a crime already underway—a child visibly dying while the world looked away.

Determined to give the forgotten girls their names back, Sarah curated an exhibition titled “Hidden in Plain Sight.

” At its center hung the 1887 photograph, displayed alongside medical analysis, court testimony, diary excerpts, and insurance records.

Visitors stood in stunned silence.

Parents held their children closer.

Descendants wept for ancestors they had never known.

The silence had finally been broken.

Months later, Sarah stood in Mount Auburn Cemetery, before five small, weathered stones hidden beneath old oak trees.

No names.

Only dates.

A mother’s secret memorial, placed where no one would ask questions—but where she could still remember.

Sarah laid white roses on the ground, one for each child.

“You are not forgotten,” she whispered.

That photograph no longer belonged to the past.

It had become a warning.

A reminder that evil often hides behind respectability.

That silence protects the guilty.

And that sometimes, the truth survives—not in words, but in images patiently waiting for someone brave enough to look closely.

News

🌴 Population Shift Shakes the Golden State: What California’s Migration Numbers Are Signaling

📉 Hundreds of Thousands Depart: The Debate Growing Around California’s Changing Population California has long stood as a symbol…

🌴 Where Champions Recharge: The Design and Details Behind a Golf Icon’s Private Retreat

🏌️ Inside the Gates: A Look at the Precision, Privacy, and Power of Tiger Woods’ Jupiter Island Estate On…

⚠️ A 155-Year Chapter Shifts: Business Decision Ignites Questions About Minnesota’s Future

🌎 Jobs, Growth, and Identity: Why One Company’s Move Is Stirring Big Reactions For more than a century and…

🐍 Nature Fights Back: Florida’s Unusual Predator Plan Sparks New Wildlife Debate

🌿 From Mocked to Monitored: The Controversial Strategy Targeting Invasive Snakes Florida’s battle with invasive wildlife has produced many…

🔍 Ancient Symbols, Modern Tech: What 3D Imaging Is Uncovering Beneath History’s Oldest Monument

⏳ Before the Pyramids: Advanced Scans Expose Hidden Features of a Prehistoric Mystery High on a windswept hill in…

🕳️ Secrets Beneath the Rock: Camera Probe Inside Alcatraz Tunnel Sparks Chilling Questions

🎥 Into the Forbidden Passage: What a Camera Found Under Alcatraz Is Fueling Intense Debate Alcatraz Island has…

End of content

No more pages to load