🩸 “Faith, Fear, and a Chilling Silence: Mel Gibson Exposes the Untold Ordeal Behind The Passion of the Christ”

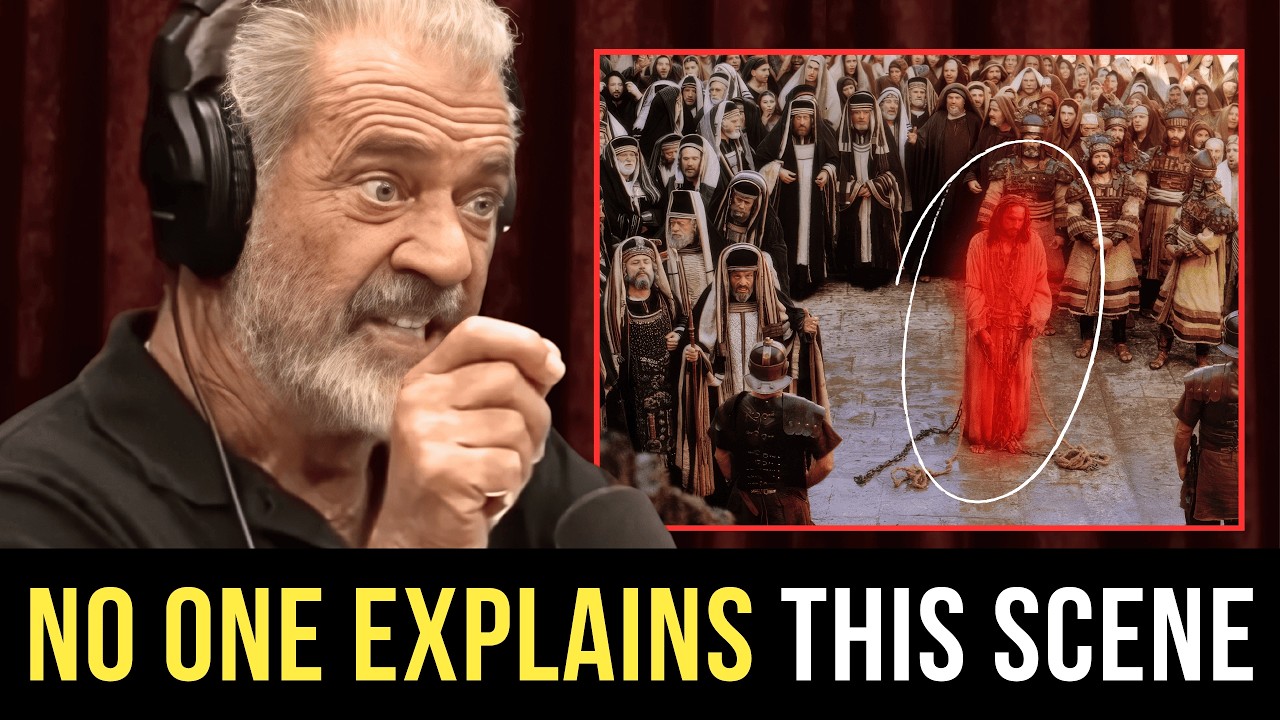

When Mel Gibson first committed to making The Passion of the Christ, he knew he was stepping into forbidden territory, but even he could not have predicted the scale of resistance that would follow.

From the earliest whispers of the project, alarms went off across Hollywood like a fire drill no one wanted to acknowledge.

Studios distanced themselves, agents advised caution, and friends quietly suggested he rethink everything.

Gibson has now admitted that the resistance wasn’t subtle; it was visceral, almost primal, as if the film itself represented something people were afraid to confront.

He recalls rooms going quiet when the project was mentioned, conversations abruptly changing direction, and a strange sensation that he had crossed an invisible line no one had warned him about.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(749x0:751x2)/mel-gibson-jim-caviezel-passion-of-the-christ-011025-b56ede5f38984f29a55e61b745af7d8f.jpg)

Financing collapsed repeatedly, forcing him to gamble his own fortune, a move many saw as reckless but which Gibson now describes as inevitable, because no one else would touch it.

The atmosphere on set, far from the controlled chaos of a typical blockbuster, felt more like a pressure chamber.

Jim Caviezel, cast as Jesus, endured physical agony that went beyond acting, including injuries that mirrored the suffering depicted on screen.

Gibson has revealed that these moments weren’t accidents brushed aside by bravado; they weighed heavily on him, creating a moral tension between artistic truth and human cost.

He speaks of standing behind the camera, watching scenes unfold, and feeling a crushing responsibility that lingered long after “cut” was called.

According to Gibson, the cast and crew sensed they were part of something volatile, something that could either disappear quietly or detonate in public view.

That tension, he says, bonded them, but it also isolated them from the industry they belonged to.

As the film neared completion, the backlash intensified.

Before audiences ever saw a frame, critics sharpened their knives.

Accusations flew, motives were questioned, and narratives were constructed that painted Gibson as reckless, obsessive, even dangerous.

What he reveals now is how little space there was for nuance.

The conversation wasn’t about filmmaking anymore; it was about control, perception, and fear of influence.

Gibson describes reading early condemnations and realizing that many critics had already decided what the film represented without seeing it.

The silence that followed from colleagues he once considered allies was, to him, louder than the criticism itself.

Phone calls stopped.

Invitations vanished.

It was as if the industry had collectively agreed to hold its breath until the storm passed—or until he did.

Then came the release, and with it, the shock that no one could contain.

Audiences poured into theaters in numbers that defied every prediction.

The same film that was supposed to marginalize Gibson instead ignited a global conversation.

Churches organized screenings, families returned multiple times, and viewers emerged shaken, emotional, and divided.

Gibson admits that the success was overwhelming, not just financially but psychologically.

He watched as box office numbers climbed and criticism grew even harsher, a paradox that left him feeling both vindicated and targeted.

The film’s impact exposed a fault line in culture, and Gibson found himself standing alone on it, absorbing pressure from both sides.

What followed, according to Gibson, was the strangest part of all.

After the noise reached its peak, there was a silence so profound it felt unnatural.

Offers dried up.

Projects stalled.

Conversations that once flowed easily became strained or nonexistent.

He describes walking into rooms where smiles didn’t reach eyes, where unspoken judgments hung in the air.

This wasn’t the dramatic exile people imagine; it was subtler, colder, and more effective.

Gibson now frames it as a lesson in how power operates quietly, not through bans or declarations, but through absence and neglect.

In reflecting on those years, Gibson doesn’t present himself as a martyr, but neither does he downplay the cost.

He acknowledges his own flaws, his own battles, and the ways controversy fed upon itself.

Yet he insists that the reaction to The Passion of the Christ revealed something deeper about fear of narrative, fear of belief, and fear of uncontrolled success.

He speaks of moments alone, replaying decisions, wondering whether truth was worth the price paid.

What haunts him most, he says, isn’t the criticism, but the realization of how quickly admiration can turn into avoidance when a project challenges the status quo.

Today, as he finally speaks openly, there is no dramatic revenge, no explosive accusation.

Instead, there is a calm, unsettling clarity.

Gibson describes the experience as walking through fire and emerging changed, stripped of illusions about acceptance and belonging.

The film remains, untouched by the years, continuing to provoke and inspire, while the industry that once recoiled has slowly, cautiously, begun to acknowledge its impact.

The silence that followed its release, Gibson suggests, was not emptiness but a message—a reminder of the unspoken rules governing influence and belief.

And now that he has finally revealed what really happened, the question lingers in the air, heavier than ever: was the world ready for that truth then, or are we only beginning to confront it now?

News

🌴 Population Shift Shakes the Golden State: What California’s Migration Numbers Are Signaling

📉 Hundreds of Thousands Depart: The Debate Growing Around California’s Changing Population California has long stood as a symbol…

🌴 Where Champions Recharge: The Design and Details Behind a Golf Icon’s Private Retreat

🏌️ Inside the Gates: A Look at the Precision, Privacy, and Power of Tiger Woods’ Jupiter Island Estate On…

⚠️ A 155-Year Chapter Shifts: Business Decision Ignites Questions About Minnesota’s Future

🌎 Jobs, Growth, and Identity: Why One Company’s Move Is Stirring Big Reactions For more than a century and…

🐍 Nature Fights Back: Florida’s Unusual Predator Plan Sparks New Wildlife Debate

🌿 From Mocked to Monitored: The Controversial Strategy Targeting Invasive Snakes Florida’s battle with invasive wildlife has produced many…

🔍 Ancient Symbols, Modern Tech: What 3D Imaging Is Uncovering Beneath History’s Oldest Monument

⏳ Before the Pyramids: Advanced Scans Expose Hidden Features of a Prehistoric Mystery High on a windswept hill in…

🕳️ Secrets Beneath the Rock: Camera Probe Inside Alcatraz Tunnel Sparks Chilling Questions

🎥 Into the Forbidden Passage: What a Camera Found Under Alcatraz Is Fueling Intense Debate Alcatraz Island has…

End of content

No more pages to load