The rain came down in sheets so thick the world outside the window barely existed.

It drummed against the warped glass of the tiny upstairs room, ran in dark veins down the pane, and seeped through the rotting frame to gather in a cold puddle on the floor.

The lightbulb on the ceiling had burned out three days earlier, so the only light came from a single candle burning low in a chipped saucer.

Its flame trembled with every gust, casting nervous shadows that crawled across the peeling walls.

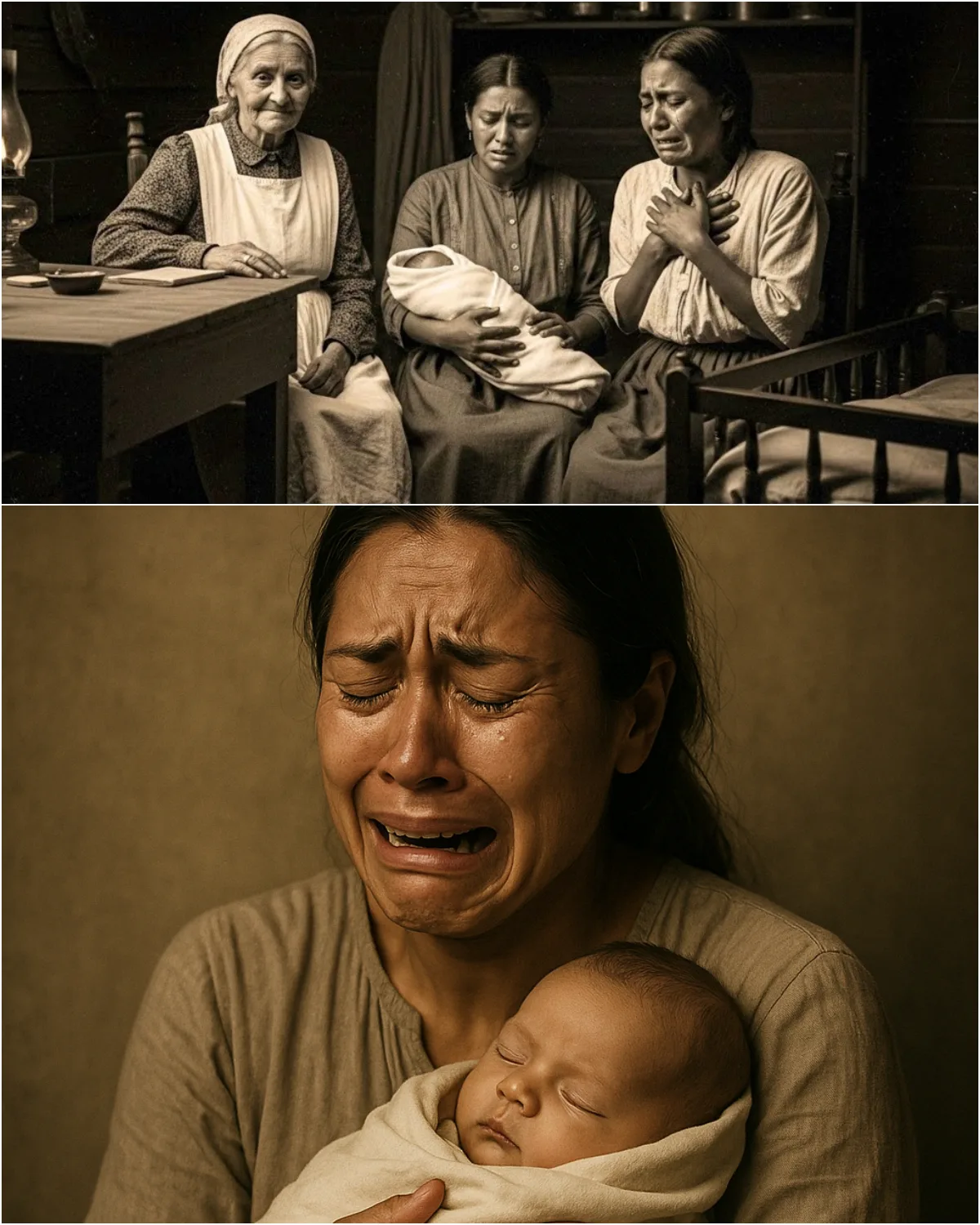

Olivia Carter clung to the thin mattress as another contraction tore through her, ripping a raw sound from her throat that hardly sounded human.

She was nineteen, barefoot, and terrified in an old T-shirt someone had given her at the shelter.

Sweat mixed with tears on her face.

She’d bitten her bottom lip so hard it bled.

“Good, good,” the older woman at the foot of the bed murmured.

“Breathe, sweetheart.

Just like I showed you.

Her name was Mrs.Carmichael.

In the poor neighborhoods around the Atlanta rail yards, her name moved from mouth to mouth in the same tone reserved for saints and ghosts.

She’d been a midwife for as long as anyone could remember — forty years, maybe more.

She delivered babies in apartments with broken heaters, in trailers that leaned to one side, in motel rooms paid by the week.

She came when women couldn’t afford a hospital, when they didn’t have insurance, when they needed things kept quiet.

Especially when they needed things kept quiet.

Mrs.Carmichael’s hair was silver and tightly pinned back, though thin wisps escaped around her temples.

Her hands, thick and veined, moved with a confidence that made hospital doctors seem like clumsy boys.

She smelled faintly of antiseptic and menthol lozenges.

Her leather medical bag sat open on the floor beside her, its lining cracked from years of use, stuffed with instruments that gleamed in the candlelight and vials with handwritten labels.

“You’re almost there,” she said, voice low, almost soothing.

“Just a little more and this will be over.

Over.The word sent a strange chill through Olivia, like cold water poured down her spine.

She couldn’t have said why.

She had come to this woman because there was nowhere else to go.

Ryan had made sure of that.

He had been charming and careful and exactly the kind of boy girls like her were supposed to stay away from.

His family lived three neighborhoods and a lifetime away, in a world of manicured lawns, brick homes, and security lights.

He drove a shiny silver car whose monthly payment could have covered Olivia’s rent for a year.

He went to college.

Her job was cleaning offices after people like him went home.

He had told her she was different.

Special.Smarter than other girls.

He had traced constellations on her arm with his finger while they lay in the backseat of his car at the edge of the city, promising a future where the difference between their worlds wouldn’t matter.

The first time she told him she was late, he’d laughed, kissed her, pulled her closer.

The second time, he went quiet.

By the time the test turned positive, his texts read like legal disclaimers.

You can’t keep it, Liv.

You know my parents would never accept that.

I’ll help you… but you have to do the right thing.

When she refused the cash he tried to press into her hands, his warmth iced over.

Suddenly she was “being manipulative.

” Suddenly she had “planned this.

” Within a week, he had blocked her number and vanished into his safe, well-lit life.

Three days later, the manager of the office cleaning company called her into his office to say her “attendance was no longer reliable” and they were “letting her go.

” No reference.

No attempt to hide the fact that someone with money had made a phone call.

Her mother lasted longer, though not by much.

“Olivia Marie Carter, you are not bringing shame into my house,” she’d shouted, Bible in one hand, the other shoving clothes into a trash bag.

“Do you want people at church to whisper about us? Do you want Pastor Raymond looking at me like I failed you?”

“Mom, it’s your grandchild,” Olivia had pleaded.

“No,” her mother had hissed, eyes bright with fear and years of swallowed humiliation.

“It is a sin you chose.

And you can take it with you when you leave.

So Olivia had left.

She bounced through couches and shelters, landed in a boarding house where six rooms shared one bathroom and the kitchen smelled permanently of burnt grease.

She stopped going to church.

She stopped answering unknown numbers.

Her world shrank to her small room, her swelling belly, and the rhythmic ache in her lower back that grew daily.

The social workers at the clinic had talked about adoption, about agencies, about waiting lists of couples aching for a child.

It all sounded like paperwork and strangers and her baby being whisked away forever.

Then another woman in the waiting room leaned over and whispered, “If you don’t want a whole system in your business, you go to Mrs.

Carmichael.

She delivers quiet.She knows what to do.

“What do you mean?” Olivia asked.

“She helps girls like us,” the woman said, shrugging.

“Cheap.No questions.No lectures.

No judge, no caseworker, no one calling your mom.

She… handles things.

The nurse called the other woman’s name before Olivia could ask more.

But that night, the name Mrs.Carmichael seemed to hum in the air around her like a tune she couldn’t shake.

When the contractions started early, sudden and sharp, she had walked there hunched over, one hand on the wall, following directions scribbled on a napkin.

The house stood on a quiet corner, paint peeling but lace curtains in the windows.

On the porch, a flowerpot of dead geraniums sat beneath a wind chime that tinkled in the wind.

Mrs.Carmichael had opened the door before Olivia even knocked twice.

“I know that face,” she’d said with a small, knowing smile.

“You’re in labor.Come in, honey.

Let’s get you settled.

”

Now, hours later, the storm outside howled as if it wanted to drown out Olivia’s screams.

Her world narrowed to sensation: the burn in her hips, the pressure like a vise squeezing her spine, the sweat dripping down her temples.

Time lost meaning.

At some point, Mrs.

Carmichael pushed a damp cloth to her forehead that smelled sharply of bleach and something bitter she couldn’t name.

“You’re strong,” the midwife murmured.

“Stronger than you think.

Push now.

That’s it.

Again.

”

Another contraction rose like a wave and crashed through her.

Olivia bore down, vision going white at the edges.

For an instant the room vanished — then snapped back into place with a sound.

A sound so small and fragile that at first she thought she had imagined it.

A tiny, broken cry.

It cut through the storm, through the candle flicker, through the roar in her ears, straight into her chest.

It was thin as thread but undeniably real, the first breath of a life that had only existed as a weight inside her until now.

Her baby.

Olivia’s heart flared with a wild mix of terror and wonder.

Tears spilled down her cheeks, sudden and hot, different from the tears of pain that had come before.

“He’s… he’s crying,” she gasped, throat raw.

“Is he okay? Is he—”

Mrs.Carmichael did not answer right away.

She moved quickly, almost gracefully, lifting the small, slippery bundle and turning away in one fluid motion that spoke of long practice.

The candlelit room seemed to tilt as Olivia watched the older woman carry the baby toward the far corner, where shadows pooled thick and the light didn’t quite reach.

“Wait,” Olivia whispered, trying to push herself up on shaking elbows.

“Wait, I want to see him.

Please.

I want—”

Her arms trembled.

Her muscles were jelly, her legs numb.

It felt as though invisible hands pressed her into the mattress.

She could hear cloth being moved, something metallic snapping open, the faint rustle of plastic.

The baby’s cry stuttered, turned to a soft, choking sound, then went abruptly silent.

The quiet that followed felt heavier than the storm, heavier than the world.

Olivia’s heart skidded.

“Why… why did he stop crying?” she whispered.

“What are you doing? Let me see—”

Mrs.

Carmichael straightened slowly, shoulders rising like a curtain.

When she turned back, she cradled a tightly wrapped bundle against her chest, covered so completely that no scrap of skin showed.

Her face was calm, almost serene.

Only her eyes looked strange — too flat, like stones at the bottom of a river.

“I’m so sorry, sweetheart,” she said, the sorrow in her voice smooth and practiced.

“The baby was born dead.

The words were so completely at odds with what Olivia had just heard that, for a second, they didn’t compute.

“What?” Olivia croaked.

“No, he cried.

I heard him.

I heard him—”

“You’re exhausted,” Mrs.Carmichael said softly, approaching the bed but keeping the bundle turned away.

“Sometimes after a long labor, the mind plays tricks.

There were some… movements, but there was no breath.

These things happen.

God takes little angels early sometimes, before the world can hurt them.

Olivia’s vision blurred, a wash of tears and disbelief.

“Please,” she begged.

“Just let me see him.

I can handle it.

I just need to see him once.

Just once.”

Mrs.Carmichael’s arms tightened around the bundle, subtle but unmistakable.

She shifted her body so completely between Olivia and the child that there was no angle, no glimpse to be had.

“It’s better you remember him as you imagined, not as he is,” she said.

“I’ve seen what it does to girls, looking at a stillborn baby.

Gives them nightmares.

Breaks something inside that never quite heals.

I’ll spare you that.

Trust me, dear.

“I already have nightmares,” Olivia whispered.

“I’ll have them whether I see him or not.

”

The older woman’s eyes flicked to her face, and for a brief second the softness dropped away.

Something sharper glinted underneath — assessment, calculation.

The look someone might give a piece of furniture they were considering selling.

Then it was gone.

“I’ll handle everything,” Mrs.

Carmichael said briskly.

“The paperwork.

The burial.

There’s a little place outside the city where they rest the stillborns.

A peaceful place.

We can do a small prayer tomorrow if you’re up to it.

”

She glanced at the clock, then at the gape in Olivia’s gaze, and seemed to decide that was enough.

Turning away once more, she tucked the bundle into a faded canvas tote that looked too ordinary for what it held.

“I’ll be back in a minute,” she said.

“Try to rest.

Olivia watched, numb, as the midwife slipped on her raincoat, shouldered the tote with the same casualness as a woman heading to the grocery store, and disappeared down the stairs.

The front door opened.

Rain roared louder.

The door shut.

Then there was only the storm and the candle and Olivia’s own uneven breathing.

For days afterward, life moved as if underwater.

Time stretched and folded.

She drifted between sleep and waking, pain and numbness.

Milk leaked from her breasts, soaking the worn shirts she rotated.

Her body relentlessly prepared to feed a child that no longer existed.

She wrapped herself in blankets and stared at the water stains on the ceiling until the patterns turned into faces.

Sometimes at night she woke up certain she had heard it again — that thin, desperate cry.

She would sit up, heart pounding, eyes searching the dark for a crib that wasn’t there.

The room stayed stubbornly empty except for the chair in the corner and the small dresser with the secondhand baby clothes she hadn’t had the heart to throw away.

“It was dead,” she whispered to herself, over and over.

“He said it was dead.

But memories didn’t care about declarations.

In the quiet hours, the sequence replayed: the contraction, the sound, the swift turn of the midwife’s body, the sudden silence.

The way Mrs.Carmichael’s hands had moved with a kind of choreography in the shadows.

After two weeks, she tried to go back to looking for work.

Her stomach had flattened some, but the way she walked, the way she winced when she bent, the way her eyes seemed hollow — it all betrayed her.

At an interview to clean rooms at a roadside motel, the manager looked her over and said, “We don’t want any trouble here.

We run a respectable place.

“Trouble?” Olivia echoed faintly.

“The kind you already brought somewhere else,” he replied, eyes flicking to her chest, where breast pads bloomed faint circles under her shirt.

“We don’t need that.She left before he could see her cry.

She found a job eventually unloading produce at a dingy grocery store where nobody asked questions as long as she showed up at 5 a.

m.

and didn’t complain when the boxes were too heavy.

The pay was bad, but at least the work exhausted her too much to think for a few hours a day.

It was there, lining up crates of oranges near the entrance one rainy afternoon, that she noticed the flower stand.

The woman who ran it was in her early thirties, with dark hair pulled into a messy ponytail and hands stained green from stems.

There was a heaviness around her eyes that no amount of makeup could hide, like bruises that had been there for years.

She moved carefully, as if her bones hurt.

“Hey,” the woman said that first day, offering a tired smile.

“You work the morning shift too?”

“Yeah,” Olivia replied.“I’m Olivia.“Emma,” the woman said.“Emma Boyd.”

They didn’t talk much at first.

Just quick nods and small comments about the weather, the price of roses, the annoying customers.

But sometimes Olivia would catch Emma watching a mother walk past with a toddler, something raw flickering across her face.

Sometimes Emma would pause, one hand resting on her belly absentmindedly, the gesture so instinctive and empty that it twisted something in Olivia’s chest.

One slow afternoon, with rain drizzling and hardly any customers, Emma walked over to where Olivia was restocking potatoes.

“You look tired,” Emma said gently.

“New baby at home?”

The question caught in Olivia’s throat like a hook.

“I…” She swallowed.“He died.At birth.A month ago.”

Emma’s face changed in an instant — not with polite sympathy, but with a sharp, startled recognition.

“Who delivered?” she asked softly.

Olivia hesitated.“An older woman.Home birth.

She… she lives a few streets over from Parkview.

House on the corner, with the broken porch steps.

Her name is—”

“Mrs.Carmichael?” Emma finished, voice barely above a whisper.

The potatoes blurred.

“Yes,” Olivia said.“How did you—”

Emma looked around, as if the air itself might be listening.

The produce manager was in the back, the cashier scrolling through her phone, the security guard half-asleep on his stool.

“Do you have a break soon?” Emma asked.

“In fifteen minutes,” Olivia said slowly.

“Meet me behind the store,” Emma whispered.

“By the dumpsters.Please.

There was something in her eyes that wouldn’t let Olivia say no.

Behind the store, the rain had turned the cracked asphalt into a patchwork of shallow puddles.

The dumpsters loomed like rusting monuments.

The smell of rotting lettuce and wet cardboard hung in the air.

Emma was already there, arms wrapped tightly around herself as if bracing against more than the chill.

“When you gave birth,” she said without preamble, “did you hear your baby cry?”

Olivia’s heart stopped, then stumbled back into a frantic rhythm.

“Yes,” she whispered.

“He cried.Just once.

Then she took him to the corner and… and said he was born dead.

Emma closed her eyes.

When she opened them again, they were bright with tears that didn’t fall.

“Mine, too,” she said.

“Six years ago.Same house.Same woman.Same storm.

Olivia stared.“You… you went to her?” she asked.

“And she said—”“That she was sorry.

That sometimes babies don’t make it.

” Emma’s jaw clenched.

“I heard my daughter cry.

It was weak, like a kitten, but it was real.

Then she took her away from me.

Said it was better I didn’t see.

Said she’d take care of the burial.

No paperwork.No death certificate.Nothing.

“My God,” Olivia whispered, nausea rising.

“Did you… did you ever find—”

Emma shook her head.

“For years, I thought I was crazy,” she said.

“Thought maybe the trauma made me imagine the cry.

But then I started hearing things.

Bits of stories.

Other girls who went to the same woman.

All the same: poor, alone, scared.

All told their babies were dead.

None ever saw a body.

None ever went to a funeral.

She looked straight at Olivia, and for the first time, the heaviness in her eyes hardened into anger.

“I don’t think they were dead,” she said quietly.

“I think she sold them.

The word hung in the damp air like smoke.

“Sold?” Olivia repeated, almost choking.

“Sold to who?”

Emma let out a hollow laugh.

“Who do you think?” she said.

“People who can pay.

Images flashed through Olivia’s mind: brick houses behind iron gates, driveways with luxury cars, parents strolling through parks with fair-skinned children, family photos on mantels.

Ryan’s neighborhood.

Ryan’s world.

“You don’t know that,” Olivia said, but even as the words left her mouth, they felt thin.

“No,” Emma agreed.

“I can’t prove it.

Yet.But I’ve been listening.Watching.

I’ve seen her leave late at night with that same blue canvas bag.

I’ve seen her walk to the edge of her neighborhood and get into nice cars that don’t belong there.

Always with that bag.”

Olivia thought about the tote.

The way Mrs.Carmichael had slipped it over her shoulder with such casual ease, as if she’d done it a hundred times.

The way she’d said, There’s a little place outside the city where they rest the stillborns.

“You think my baby is alive,” Olivia whispered.

“Somewhere in this city.

In someone else’s house.”

“I think it’s possible,” Emma said.For yours.For mine.

For… God knows how many others.”

A slow, coiling heat unfurled in Olivia’s chest, something different from grief.

Grief was heavy.

This was sharp.

“Then we find out,” she said.

“We get proof.

We can’t go to the police with just… feelings.

”

“Cops?” Emma snorted.

“Half of them know people in those neighborhoods.

Some probably have cousins who ‘adopted’ that way.

These people have money.

Lawyers.

They’ll bury us faster than any evidence.

”

“Then we don’t start with them,” Olivia said slowly, thinking of the free newspapers left outside the grocery store each morning.

Headlines about corruption, exposés about city officials.

“We start with someone who talks for a living.

“A reporter?” Emma asked.

“If we can give them something solid,” Olivia said, feeling the idea take shape, “they can’t ignore it.

Not if there are more like us.

Emma looked at her for a long moment, assessing.

Something in her gaze softened.

“You’re stronger than you look,” she said.

“So are you,” Olivia answered.

It was the beginning.

The weeks that followed were a study in quiet obsession.

After their shifts, the two women huddled in Emma’s small apartment, making lists on the back of old receipts.

Names of girls they remembered from the clinic waiting room.

Whispers overheard at laundromats.

Snatches of gossip in shelter hallways.

They knocked on doors in crumbling buildings and sat at sticky kitchen tables while women stirred cheap coffee and tried not to cry.

They told their stories first, to earn trust.

In living room after living room, the pattern repeated.

Contractions in the night.

A neighbor saying, “Call Mrs.

Carmichael, she knows what to do.

” The older woman arriving with her bag and her calm voice.

The sound of a baby’s first breath — a cry, a whimper, a gurgle — cut off too quickly.

The declaration: I’m so sorry, it was born dead.

The body hidden.

The burial handled.

No questions asked, no papers signed.

Very few of the women had jobs that offered insurance.

Fewer still had family willing to stand beside them.

They lived in the cracks, and in those cracks, Mrs.

Carmichael had built something like a business.

“How many do you think?” Olivia asked one night, staring at the names on their growing list.

“At least twenty that we know of,” Emma said.

“Over the last ten years.

But she’s been doing this work a lot longer than that.

A baby a year.Two.More? The numbers became a blur.

Each name was a knife.

If they wanted to be believed, they needed more than stories.

“We have to catch her,” Emma said.“In the act.

The plan they built was simple and dangerous.

Emma would go back to Mrs.

Carmichael, pretending to be pregnant again.

She would say she couldn’t raise another child, not alone, not in her position.

She would ask Mrs.

Carmichael to “take care of it” and hint that she didn’t want to know the details.

“You’re not actually…” Olivia began, alarmed.

“No,” Emma said.

“I can fake it for a few months.Baggy clothes.

Loose jackets.People see what they expect to see.”

“And I’ll be there,” Olivia said.“Outside.

We get her to talk, we record it.That’s proof.”

Borrowing a recorder took two favors and a promise of free flowers for a month to one of Emma’s suppliers.

The device was small enough to tuck inside a pocket, its red light easily hidden beneath a scrap of tape.

The night Emma went to see Mrs.

Carmichael again, the rain had returned, though lighter this time, a mist that turned streetlights into blurred halos.

From the cover of a hedged yard across the street, Olivia watched Emma climb the sagging porch steps.

Her heart was pounding so hard she could feel it in her throat, in her fingertips.

The door opened.

Mrs.

Carmichael’s figure appeared in the frame, haloed by warm lamplight.

Even from that distance, Olivia recognized the practical bun, the squared shoulders, the tidy cardigan buttoned up to her neck.

The conversation inside lasted nearly forty minutes.

Later, when they played it back in Emma’s apartment, the recorded voices sounded ghostly, like echoes from underwater.

“Mira, honey, this is a business like any other,” Mrs.

Carmichael’s voice said, a hint of humor in it that made Olivia’s stomach turn.

“There are girls like you who can’t raise a child, and couples out there who’d pay anything to have one.

I just connect the dots.

Everybody wins.

”

“How much… would you pay?” Emma’s voice asked, carefully shaky.

A number.

Not large, but not small.

Less than what a lawyer might charge for a day’s work.

A fraction of what the couples would likely pay on their side.

“But only if the baby’s healthy and light-skinned,” Mrs.

Carmichael added casually.

“Blond or blue eyes, those are like gold.

People want a baby that can pass for theirs.

Darker ones are harder to place.

Unless the family’s darker too, but those families don’t usually have that kind of money.

”

Olivia flinched at the casual racism bundled in the words, the way human life and skin tone sat side by side like line items on a price list.

“And what if…” Emma’s voice hesitated on the recording.

“What if I changed my mind after giving birth?”

A dry laugh from the midwife.

“They never do,” she said.

“But if some girl gets ideas, I handle it.

I tell her the baby was born dead.

Make her sign a paper saying I’ll take care of the burial.

She has no way to prove anything.

And if she tries to make noise, I remind her nobody listens to a girl who tried to get rid of her baby.

A woman like that? She’s garbage in this society.

Worse than garbage.People cross the street not to breathe the same air.

Silence followed, broken only by the faint hum of the tape.

On the couch, Emma pressed her knuckles to her mouth.

Olivia stared at the recorder as if it might bite.

“There it is,” Emma said finally, voice flat.“Proof.”

“Proof that she stole our children,” Olivia whispered.

Proof that the cry had been real.

Proof that the nightmare was not the fragility of their minds, but the solidity of the world’s cruelty.

The days that followed moved quickly.

The reporter they eventually found — a woman named Rachel Klein who had written about police corruption and housing scams — listened to the tape twice without saying a word, jaw tightening with each repetition.

When Emma and Olivia laid out the stories, the names, the patterns, Rachel didn’t look surprised, only tired in a way that spoke of too much truth and too little justice.

“This isn’t just one midwife,” she said.

“This is a pipeline.

You know that, right? She’s not forging birth certificates by herself.

She’s not placing babies in wealthy neighborhoods with nothing but a prayer.

There are doctors.

Lawyers.

Maybe even judges and social workers in on it.

”

“Will you still write it?” Olivia asked, throat dry.

Rachel looked up, eyes sharp.

“Especially because of that,” she said.

What happened after the article came out — the outrage, the arrests, the counter-lawsuits, the debates on talk shows about “illegal adoptions” and “desperate women” — would ripple through the city for years.

Some nights, watching the news on the small TV in the boarding house, Olivia saw Mrs.

Carmichael led out of her home in handcuffs, her calm mask slipping just enough to show anger, not remorse.

“I gave those girls an out,” she snapped at reporters as they crowded the sidewalk.

“They should be thanking me.

”

No camera caught Olivia’s face in the crowd, but she was there, a shadow among many, shaking with a cocktail of vindication and heartbreak.

Some of the babies were found.

Not many, but enough to prove the pattern.

DNA tests matched a handful of toddlers and school-aged children to mothers who had believed they’d buried empty coffins.

Those reunions were awkward, beautiful, painful in ways words couldn’t contain.

None of them were Olivia’s.

Her son, if he had survived, existed somewhere outside the net they had thrown.

In another city.Another state.Maybe even another country.

A grown child now, with a different name and a story about the day he was born that had never included her.

In the years that followed, she found work with a nonprofit that advocated for mothers’ rights, pushing for stricter oversight of adoptions and better support for pregnant women in poverty.

She sat in classrooms, telling her story to future social workers and nurses.

She stood on stages at community centers, voice steady even when her hands trembled.

“This isn’t just about stolen babies,” she would say.

“It’s about a world that made women like us easy to steal from.

It’s about how shame and silence are the best tools for people who make profit from our pain.

Sometimes, walking through the city, she would see a young man with eyes the exact shade of her father’s, or a crooked half-smile that tugged at some deep memory, and her heart would lurch.

She never stopped listening for that first cry.

On the anniversary of the night she gave birth, Olivia always found herself thinking back to the tiny upstairs room, the rain hammering the glass, the candle stuttering in its saucer.

To the way the shadows had swelled and shifted as Mrs.

Carmichael turned away with her child.

That night had been the end of one life and the beginning of another — not just for her, but for the hidden network that had thrived on women like her for decades.

She had not toppled the system.

No one story could.

But she had cracked it, just enough for light to leak through.

The mystery that had started with a single impossible cry in the dark would never be fully solved.

She would never know his name, or if he remembered her voice humming off-key lullabies into the empty air of that boarding house room.

But she knew this: somewhere, in some house, he existed because she had refused to believe the lie.

And in a world that wanted girls like her silent, that refusal was its own kind of miracle.

News

They Laughed When the Giant Cowboy Picked the Amish Girl— But Out on His Remote Ranch, She Discovered Why He Needed Her More Than Anyone Knew

Hannah first heard the sheriff’s decree before the sun was even up. “Get up this instant.” Her mother’s voice cracked…

A Christmas at the Wrong Station

Christmas Eve, 1885. Snow fell in slow, heavy flakes over the empty train platform. The wind cut through Grace Whitlow’s…

The Ranch Hands Laughed When They Sent the “Fat Girl” to Calm His Wild Stallion…

Nora Hale had never been the kind of woman people looked at twice. Not in the small town of Dusty…

“1 Minute Ago: Travis Taylor’s Secret Findings Were Released… What He Discovered at Skinwalker Ranch Is Worse Than Anyone Imagined 😨📡🚨”

“BREAKING: Dr.Travis Taylor Finally Reveals the TERRIFYING Truth Behind the Skinwalker Ranch Mystery — And It Changes EVERYTHING 😱🛑🌘” …

“The Confession No One Expected: Bryan Arnold Reveals What Drove Him Away From Skinwalker Ranch… It’s Worse Than You Think 😨📡🚨”

“At Last, Bryan Arnold Breaks His Silence — And the Real Reason He Left Skinwalker Ranch Has Experts Trembling 😱🛑🌘”…

“Fast N’ Loud Crew Silent After Terrifying Discovery Inside Rawlings’ Private Garage — This Changes EVERYTHING 😨🔧🛑”

“BREAKING: Investigators Just Entered Richard Rawlings’ Garage — And What They Found Inside Left Everyone Frozen 😱🚨🏁” The fictionalized…

End of content

No more pages to load