🩸 “They Were Never Meant to Hear This: The Ethiopian Bible Uncovers Jesus’ Final, Terrifying Words After He Rose”

The Ethiopian Bible has always occupied an uneasy position in Christian history.

Older in some respects than many Western traditions, broader in scope, and fiercely protected by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, it contains texts that never made it into the standard biblical canon.

For centuries, scholars dismissed this collection as peripheral, exotic, or theologically inconvenient.

But according to recent renewed attention, what it preserves may be closer to the raw, unfiltered aftermath of the Resurrection than anything most Christians have encountered.

The words attributed to Jesus after he rose are not polished sermons or symbolic parables.

They are sharp, almost confrontational statements that reframe the meaning of his return from the dead.

In these accounts, Jesus does not emerge calm and resolved.

He speaks with urgency, as if time itself has become unstable.

Rather than celebrating victory, he warns of distortion.

He tells his followers that his message will be altered, softened, and eventually controlled.

The Ethiopian texts suggest that Jesus anticipated not only persecution, but reinterpretation—by institutions that would claim to speak in his name while dulling the radical edge of his words.

This version of the post-Resurrection Christ is not comforting; he is alert, intense, and deeply aware of how power reshapes truth.

What makes these passages especially controversial is their tone toward authority.

Jesus is depicted as warning his disciples not to trust structures that elevate image over substance.

He speaks of future leaders who will argue over doctrine while forgetting compassion, who will worship symbols while ignoring suffering.

This stands in stark contrast to later theological traditions that emphasize order, hierarchy, and certainty.

In the Ethiopian Bible, the Resurrection does not resolve tension—it amplifies it.

Jesus returns not to calm the storm, but to warn that a greater one is coming.

The words attributed to him also challenge the idea that the Resurrection marked the end of fear.

Instead, Jesus speaks of responsibility.

Having witnessed death and crossed through it, he places the burden squarely on his followers.

According to these texts, he tells them that the miracle itself will not save the world; only what they do with the truth will.

This reframes the Resurrection as a beginning, not a conclusion, and strips it of triumphalism.

Salvation is not automatic.

It is fragile, and easily corrupted.

Western scholars have long argued that such texts were excluded for being too radical, too ambiguous, or too destabilizing.

The Ethiopian Bible’s survival outside Roman influence meant it was never fully subjected to the same processes of standardization.

As a result, it preserves a Jesus who speaks less like a distant divine figure and more like a witness to catastrophe—someone who has seen the worst and knows how easily humans repeat it.

That alone may explain why these words were allowed to fade into obscurity elsewhere.

The implications are deeply unsettling.

If Jesus truly warned that his message would be reshaped after his Resurrection, then the history of Christianity becomes not just a story of faith spreading, but of meaning narrowing.

The Ethiopian Bible suggests that silence was not accidental.

Certain words were simply too dangerous to circulate widely, especially words that questioned religious authority and predicted internal decay.

Over time, what remained was safer, more manageable, and easier to institutionalize.

Believers who encounter these passages often describe a sense of disorientation.

The Jesus they meet here does not offer reassurance about the future of the church.

He offers a warning about it.

He speaks of a world that will use his name while resisting his example, and of followers who will argue about heaven while ignoring injustice on earth.

This is not heresy; it is discomfort.

And discomfort, historically, has always been the first thing edited out.

Critics argue that these texts are symbolic or later interpretations, but defenders point to linguistic patterns and theological consistency with early Christian anxieties.

The fear of corruption, the tension between message and institution, and the emphasis on lived truth over belief alone all align with first-century realities.

What differs is the bluntness.

The Ethiopian Bible does not soften the Resurrection into closure.

It presents it as exposure.

If these words were truly spoken after Jesus rose, then the Resurrection was not meant to end debate—it was meant to ignite it.

The silence that followed in much of Christian history begins to feel less like reverence and more like avoidance.

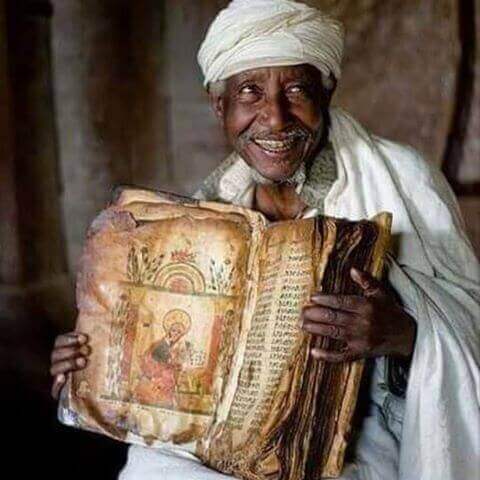

The Ethiopian Bible didn’t disappear.

It waited.

Preserved in plain sight, protected by a tradition that never fully surrendered to imperial theology, it carried a version of the story that refused to be domesticated.

Now, as fragments of that tradition resurface in public conversation, the question is no longer whether these words are comfortable or convenient.

The question is why we were never meant to hear them.

Because if Jesus really said this after conquering death, then the Resurrection was not the moment faith became easy.

It was the moment responsibility became unavoidable.

And that may be the most unsettling revelation of all.

News

🌴 Population Shift Shakes the Golden State: What California’s Migration Numbers Are Signaling

📉 Hundreds of Thousands Depart: The Debate Growing Around California’s Changing Population California has long stood as a symbol…

🌴 Where Champions Recharge: The Design and Details Behind a Golf Icon’s Private Retreat

🏌️ Inside the Gates: A Look at the Precision, Privacy, and Power of Tiger Woods’ Jupiter Island Estate On…

⚠️ A 155-Year Chapter Shifts: Business Decision Ignites Questions About Minnesota’s Future

🌎 Jobs, Growth, and Identity: Why One Company’s Move Is Stirring Big Reactions For more than a century and…

🐍 Nature Fights Back: Florida’s Unusual Predator Plan Sparks New Wildlife Debate

🌿 From Mocked to Monitored: The Controversial Strategy Targeting Invasive Snakes Florida’s battle with invasive wildlife has produced many…

🔍 Ancient Symbols, Modern Tech: What 3D Imaging Is Uncovering Beneath History’s Oldest Monument

⏳ Before the Pyramids: Advanced Scans Expose Hidden Features of a Prehistoric Mystery High on a windswept hill in…

🕳️ Secrets Beneath the Rock: Camera Probe Inside Alcatraz Tunnel Sparks Chilling Questions

🎥 Into the Forbidden Passage: What a Camera Found Under Alcatraz Is Fueling Intense Debate Alcatraz Island has…

End of content

No more pages to load