The photograph arrived without ceremony, slipped inside a plain archival box at the New York Historical Society in early January 2024.

To most eyes, it was unremarkable—just another early-20th-century studio portrait.

But when Diana Foster, a senior American archivist, lifted it into the light, she felt something tighten in her chest.

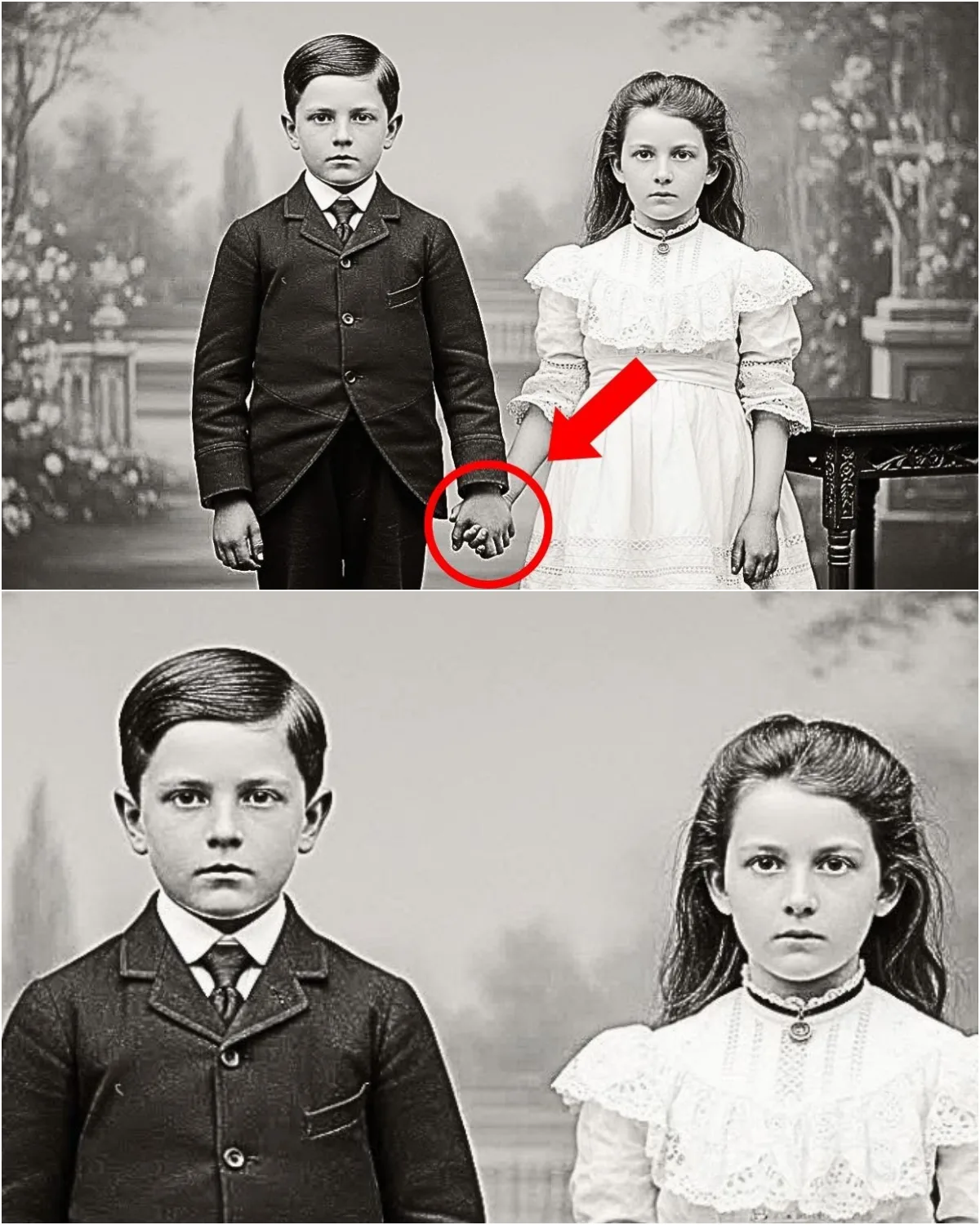

Two children stood side by side in a photographer’s studio.

A boy of about eight in a dark suit slightly too large for his thin frame.

A girl, no more than six, in a white dress trimmed with lace.

Their clothes were neat, almost formal, as if chosen for an important occasion.

But it wasn’t their clothing that unsettled Diana.

It was their hands.

They were holding each other with an intensity that felt desperate, their fingers intertwined so tightly that the girl’s knuckles had gone pale.

Their faces carried none of the mild discomfort common in old photographs.

Instead, their eyes held something far heavier—grief, fear, and a kind of knowing no child should possess.

On the back, written in faded ink, were a few chilling words:

“Emma and William Kowalsski — September 14, 1901.

Final documentation.

Family Court, New York County.

”

The word final lingered in Diana’s mind long after she placed the photograph on her desk.

She had spent twenty years reading the quiet language of archives—what documents said, and more importantly, what they avoided saying.

And she knew one thing immediately: this photograph was not taken to preserve a memory.

It was taken because something was ending.

Diana began where all archivists do—with names.

The Kowalsski surname led her quickly to immigration records.

Jan and Katarzyna Kowalsski, Polish immigrants, had arrived at Ellis Island in 1894 with two small children: William, age two, and Emma, still an infant.

Like thousands of others, they settled on the Lower East Side, in a cramped tenement that smelled of coal smoke, sweat, and boiled cabbage.

Census records painted a familiar story.

Jan worked long hours in a garment factory.

Katarzyna took in sewing when she could.

The children attended school.

They were poor, but together.

That togetherness did not last.

In March 1901, Jan Kowalsski died in a factory accident when a weakened floor collapsed beneath heavy machinery.

Four months later, Katarzyna succumbed to tuberculosis.

By summer’s end, William and Emma were alone in a city that barely noticed such losses.

Orphans were common then.

Compassion was not.

The notation on the photograph led Diana to the family court archives, buried deep beneath Manhattan in rooms thick with dust and forgotten decisions.

After hours of searching, she found the file:

“In the Matter of William Kowalsski and Emma Kowalsski, Minor Children.

”

What she read made her hands tremble.

The court had declared the children “dependent wards of the state.

” Almost immediately, petitions followed—not for adoption, not for family placement, but for custody for labor.

A wealthy woman on Fifth Avenue requested Emma, citing “domestic service and Christian instruction.

”

A farmer upstate requested William, citing “agricultural labor and moral education.

”

No one argued to keep them together.

On September 13, 1901, a judge approved both petitions.

The next morning, September 14, the photograph was taken.

The day after that, the children were separated forever.

A handwritten note from a caseworker delivered the truth with brutal indifference:

“Children extremely distressed at separation.

Boy had to be physically removed from his sister.Girl became hysterical.

Recommend less advanced notice in future cases to reduce emotional displays.

Diana closed the file and sat in silence.

The photograph on her desk no longer felt still.

It felt loud.

Tracing Emma’s life was painfully easy.

By 1905, census records listed her as a servant in the Fifth Avenue household of Caroline Ashford, wife of a powerful banker.

Not a ward.

Not a daughter.

A servant—at ten years old.

Decades later, Diana found a short memoir written by Emma near the end of her life.

Its words were spare, but devastating.

Emma wrote of waking before dawn, scrubbing floors, carrying coal, and being punished for speaking Polish or asking questions.

She wrote of loneliness that pressed so hard it felt physical.

And she wrote—again and again—about William.

“I cried for my brother every night.

I did not know where he was.

I was told to forget him.I never did.

Emma searched for William for over sixty years.

She never found him.

William’s trail was harder to follow.

Upstate records showed him listed as a farm laborer at age twelve.

A newspaper notice from 1906 mentioned a “farm accident” that left him injured.

Letters to the editor from concerned neighbors described a thin city boy working in freezing weather, bruised, frightened, and closely watched.

Authorities dismissed the complaints.

By 1910, William vanished from records entirely.

No death certificate.

No marriage.

No draft registration.

He disappeared into history, like thousands of children whose labor was taken and whose lives were never documented.

Standing once more before the photograph, Diana finally understood its full weight.

The children had known.

The court hearing had already happened.

The orders were signed.

The clothes they wore were likely purchased for appearances, to make the moment look respectable.

Their tears had been wiped away, but not erased.

They held hands because it was the last thing they could control.

The photograph was not a portrait.

It was evidence.

In September 2024, exactly 123 years after the image was taken, Diana curated an exhibition titled:

“Separated: When the System Broke the Family.

The photograph of Emma and William filled an entire wall.

Visitors stood in silence before it, drawn first to the clasped hands, then to the eyes.

Many cried.

Some turned away.

Emma’s descendants came too.

They saw their grandmother as a frightened child, frozen in the moment everything was taken from her.

William’s fate remained unknown, but his absence became part of the story—a space history refused to fill.

Diana ended the exhibition with a single line beneath the photograph:

“This was the last time they were together.

”

That night, after the gallery emptied, Diana returned alone.

She stood before the image once more, thinking of how many similar photographs still sat quietly in archives, mislabeled, misunderstood, waiting for someone to look closer.

History often calls these decisions necessary.

The courts called them progress.

The paperwork called it final.

But the photograph told a different truth.

It showed two children who loved each other, who understood loss, and who were never given a choice.

And in that understanding, Diana realized something both haunting and hopeful:

as long as their story was told, they were no longer invisible.

News

🌴 Population Shift Shakes the Golden State: What California’s Migration Numbers Are Signaling

📉 Hundreds of Thousands Depart: The Debate Growing Around California’s Changing Population California has long stood as a symbol…

🌴 Where Champions Recharge: The Design and Details Behind a Golf Icon’s Private Retreat

🏌️ Inside the Gates: A Look at the Precision, Privacy, and Power of Tiger Woods’ Jupiter Island Estate On…

⚠️ A 155-Year Chapter Shifts: Business Decision Ignites Questions About Minnesota’s Future

🌎 Jobs, Growth, and Identity: Why One Company’s Move Is Stirring Big Reactions For more than a century and…

🐍 Nature Fights Back: Florida’s Unusual Predator Plan Sparks New Wildlife Debate

🌿 From Mocked to Monitored: The Controversial Strategy Targeting Invasive Snakes Florida’s battle with invasive wildlife has produced many…

🔍 Ancient Symbols, Modern Tech: What 3D Imaging Is Uncovering Beneath History’s Oldest Monument

⏳ Before the Pyramids: Advanced Scans Expose Hidden Features of a Prehistoric Mystery High on a windswept hill in…

🕳️ Secrets Beneath the Rock: Camera Probe Inside Alcatraz Tunnel Sparks Chilling Questions

🎥 Into the Forbidden Passage: What a Camera Found Under Alcatraz Is Fueling Intense Debate Alcatraz Island has…

End of content

No more pages to load