THE WOMAN SOLD FOR NINETEEN CENTS

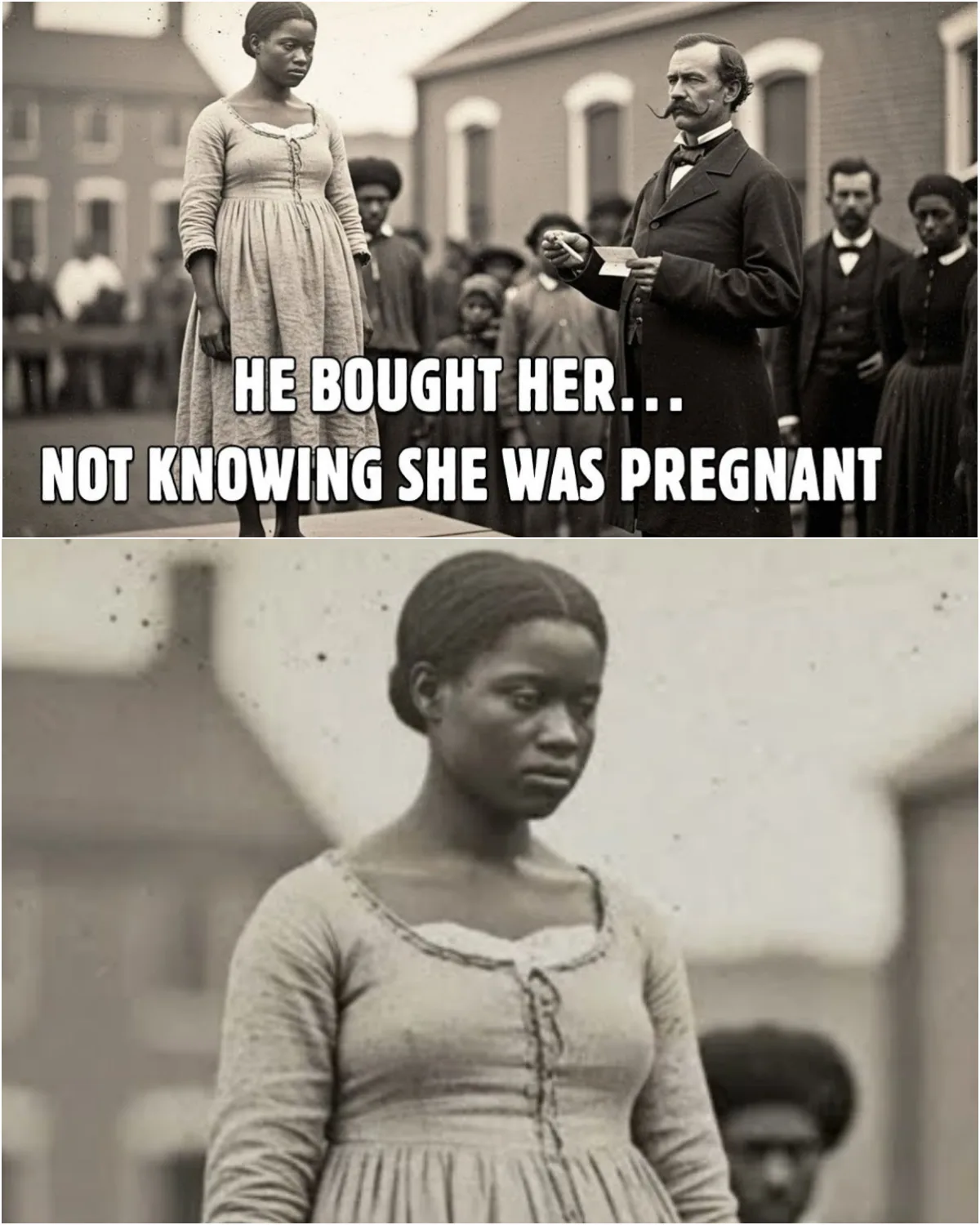

On the morning of November 7, 1849, the courthouse yard in Natchez was buzzing with business. Wagons creaked beneath their loads; men argued over the price of hogsheads of cotton; a sheriff’s deputy pinned auction notices to the weathered wooden post at the foot of the steps. The air smelled of mud, sweat, and tobacco.

At the bottom of the sheet of paper—below livestock, tools, and miscellaneous property—stood a final line.

Diner — Female, aged approx. 22 — Starting bid: $0.19

The deputy who posted it shrugged. He had seen strange things at slave auctions, but this was new. Nineteen cents was the price one paid for a cracked tin bucket or a handful of nails—not a woman of childbearing age, healthy, and five months pregnant.

Even the traders stood back from the block.

Those who dealt in human property knew that prices told stories. A high price meant value, fertility, productivity. A low price meant suspicion: disease, madness, defiance.

But this price—nineteen cents—was a message no one could decipher.

She stood quietly beside the post, hands folded in front of her belly. She wore a faded calico dress, the same one she had arrived in after a night’s confinement in the jailhouse cellar. Her skin was smooth; her posture straight. Her eyes, dark and calm, seemed to absorb everything: the mud on the boots, the coins, the stares.

She did not cry. She did not plead.

She simply waited.

Her name appeared twice in official records over the next decade—each time spelled differently. Diner. Diana. In the oral stories of the Black women who hid her during the war she was called Dinina.

But on that November day, she was just a line of ink and a price.

The auctioneer, a red-faced man named Dunlop, cleared his throat as he mounted the steps. He was used to swagger, to barked numbers and eager hands, to the grotesque theater of buying and selling human lives. But when he glanced at the last line on his ledger, he hesitated.

“Lot 17,” he announced. “Female, twenty-two, trained for domestic labor. Starting price—”

He paused, embarrassed.

“—nineteen cents.”

Laughter rippled through the yard, then died into an uneasy silence.

A trader near the front spat into the mud.

“Hell, Dunlop. Why not just give her away?”

Another muttered, “There’s a reason for that price. You can’t sell bad luck.”

No one moved. Men who would normally fight over a healthy enslaved woman refused to raise a hand. A price so low was not a bargain.

It was a warning.

Dunlop tried again.

“Who’ll open at nineteen cents?”

Nothing.

The wind rattled the dead magnolia leaves. A wagon rolled past. A baby cried somewhere up the road.

Still nothing.

By law, Dunlop had to offer each lot three times. If no bid came, the person would be remanded to the county work farm—a brutal place where prisoners were starved, whipped, and often died within months. No one ever returned healthy.

The woman’s lips parted. For the first time, she spoke, though barely above a whisper.

“Please,” she said. “Not there.”

Her voice was soft, but the words carried.

A murmur spread. Men who had spent their lives ignoring the pleas of enslaved people suddenly shifted uncomfortably. It was not the content—it was the tone. Calm. Controlled. Not fear, but something like resolve.

Dunlop swallowed.

“Nineteen cents. Someone take her.”

Still no one.

Then a voice from the edge of the crowd called, “I’ll bid.”

Heads turned.

A man on a mule sat at the periphery, hat pulled low. He looked like a drifter—coat worn at the elbows, beard untrimmed, boots cracked with age. No one knew him. He had arrived at dawn, bought a cup of coffee, and had said nothing since.

He lifted one hand.

“Nineteen cents,” he said.

Dunlop stared, incredulous.

“Going once.”

No challenge.

“Going twice.”

The crowd held its breath.

“Sold.”

The drifter swung down from his mule, paid the exact coins without counting, and walked to the woman.

He did not touch her.

He simply said, “Come.”

She followed.

And just like that, she left the auction block for the price of a handful of nails.

The man called himself Samuel Brooks. Whether that was his real name, no one ever proved. He owned no plantation. He had no family nearby. He had a small rented cabin on the outskirts of the county and a job hauling timber for the riverboats. People assumed he was poor, transient, unremarkable.

Yet he treated the woman he had bought as something more than property.

He gave her his bed and slept on the floor. He shared his food. He asked nothing of her except that she rest, because she was carrying a child.

The first night, when she sat at his table eating cornbread and beans, he said:

“You’re safe here.”

She looked at him steadily.

“No place here is safe.”

He nodded.

“That’s true.”

He waited.

“Will you tell me your name?”

She hesitated.

Finally she said, “Dinina. That’s what my mother called me.”

“Dinina,” he repeated.

Then, softly, “I won’t ask about the father.”

Her gaze dropped to her hands.

“You should,” she said. “Because if anyone finds me, they’ll kill me. And they’ll kill the child, too.”

Brooks stared. He had known there was more to the nineteen cents. He had sensed danger the moment he saw her on the block.

But he did not know how deep it went.

“Who’s looking for you?” he asked.

Dinina didn’t answer.

She only said, “Men with horses. Men with dogs.”

For days, nothing happened.

Brooks worked. Dinina cooked, swept, mended torn shirts. She spoke little. At night she sat by the fireplace, hands on her belly, eyes distant.

The silence held stories.

One evening a knock came at the door.

When Brooks opened it, two riders sat outside.

“We’re looking for a runaway,” one said. “Belongs to the Callahan plantation. Female, twenty-two, round with child.”

Brooks leaned against the frame.

“Don’t know anything about that.”

The rider’s eyes narrowed.

“Word is she was sold yesterday. Cheap.”

Brooks shrugged.

“Lots of cheap things at auction.”

The second rider leaned forward in his saddle.

“Her owner wants her back.”

A pause.

“Badly.”

Brooks said nothing.

The men left, but not before one of them spat into the dirt and said, “If you see her, tell her running ain’t going to change blood.”

Brooks shut the door slowly.

Dinina stood in the shadows, one hand on her throat.

She whispered, “They know.”

The truth emerged over days like splinters.

Dinina had been raised in a plantation kitchen, taught to sew, cook, and pour wine. She was never whipped, never sold, never hired out. The planter—Callahan—watched her with a strange, obsessive affection.

“He thought I was his reward,” she said once, staring into the fire.

Brooks understood too quickly.

“He forced you?”

She shook her head.

“No. It was worse. He believed it was love.”

When she told him she was pregnant, Callahan’s joy turned to horror. His wife, long dead, had kept a single birth record in her Bible:

A daughter named Eliza, born to the enslaved girl Rachel — Father: Hyram Callahan.

The infant had been taken from the mother before she ever saw her face. That child had grown into Dinina.

The man who said he loved her had been her father.

Brooks exhaled slowly.

“And when he discovered…?”

She nodded.

“He wanted me to disappear.”

It was not grief that destroyed Callahan, but shame—a shame that could not be spoken. He could not flog her, could not sell her openly.

But he could send her to the auction block with a price so low that no one would touch her. Nineteen cents was not a sale.

It was a curse.

The riders returned.

Not two this time, but five.

They carried ropes.

Brooks woke Dinina at midnight.

“You must go,” he whispered. “You and the child.”

She grabbed his arm.

“You will die if you stay.”

He shook his head.

“I’ve died before.”

He handed her a small parcel: bread, dried meat, a river map.

“There’s a woman upriver,” he said. “A midwife. She owes me a debt. Tell her I sent you.”

Dinina stared at him, tears sliding down her face.

“No one owes you anything.”

Brooks smiled.

“Then I’ll call it kindness.”

When she reached the door, he added:

“Your child deserves a name that’s hers. Not his.”

Dinina nodded.

“He will have another man’s name,” she said. “Yours.”

She vanished into the trees.

Minutes later, the riders arrived. Men with torches. Men with fury.

They found Brooks waiting with an axe.

The fight lasted less than a minute. When it was over, the cabin burned. Brooks lay on the floorboards, dying. His last thought was not of the men who killed him, but of the woman he had saved for nineteen cents.

Dinina reached the river before dawn. She stood on the bank, water lapping at her ankles, and whispered:

“Samuel.”

The midwife who lived upriver—old, sharp-eyed, feared by the locals—took her in. For months Dinina slept in a lean-to and worked quietly, mending clothes, tending herbs.

In early spring, she gave birth to a boy.

She named him Samuel.

No record was ever filed.

No baptismal register.

No deed of ownership.

A child beyond price.

Six years later, in 1855, a coroner in Vicksburg signed a report for a woman found floating in the river.

Her name was written Diana.

Age unknown.

She had no scars. No marks. No story.

The official cause of death: drowning.

But among the women who had sheltered her, the memory persisted.

They said she walked into the water at twilight, holding something to her chest.

A small book, perhaps.

Or a bundle.

Her child, Samuel, was seen playing on the riverbank days later. The midwife took him and raised him as her own.

He lived to old age.

He married.

He had daughters.

One of them, when she was eighty, told a WPA interviewer:

“My grandmother was sold for nineteen cents. But she was never owned by any man.”

Every town keeps ghosts.

In Natchez, the whispers say that on cold November mornings a woman in a faded calico dress walks the courthouse yard. She pauses where the auction post once stood.

Sometimes people hear coins clink on wood.

Nineteen cents.

A number that was meant to mean nothing—worthless, disposable, erased—became the key to a story that refused to die.

In the end, the price was not an insult.

It was a memorial.

A reminder that even in a world built on cruelty, a single human life could defy the ledger.

News

Lot 77: The Most Beautiful Man Ever Sold, and the Mystery He Left Behind

THE MAN WHO WAS TOO BEAUTIFUL TO BE SOLD Richmond, Virginia — 1855 In the heart of 19th-century Richmond, where…

The Planter Who Married His Slave and Discovered She Was His Daughter

The Man Who Walked Into the Swamp and Was Never Seen Again The summer of 1839 was the kind that…

Seventeen Cents and a Kingdom of Ghosts

No one was ever supposed to read what was written on that slip of paper. It wasn’t a diary…

The Secret Buried in the Hills

When Don Aurelio Vargas rode back into his hacienda that March afternoon of 1858, the air above the fields…

The President, the Slave, and the Promise Made in Paris

Jefferson’s Hidden Family: The Story America Tried to Bury In September 1802, readers in Richmond, Virginia, unfolded their newspapers…

🕯️ “500 Years Locked Away: The Shocking Discovery Hidden Inside King Henry VIII’s Tomb Stuns the Entire World 😨📜”

⚰️ “Just Revealed: Archaeologists Break Open King Henry VIII’s Sealed Tomb—And What They Found Left Experts Trembling 😱👑” The decision…

End of content

No more pages to load