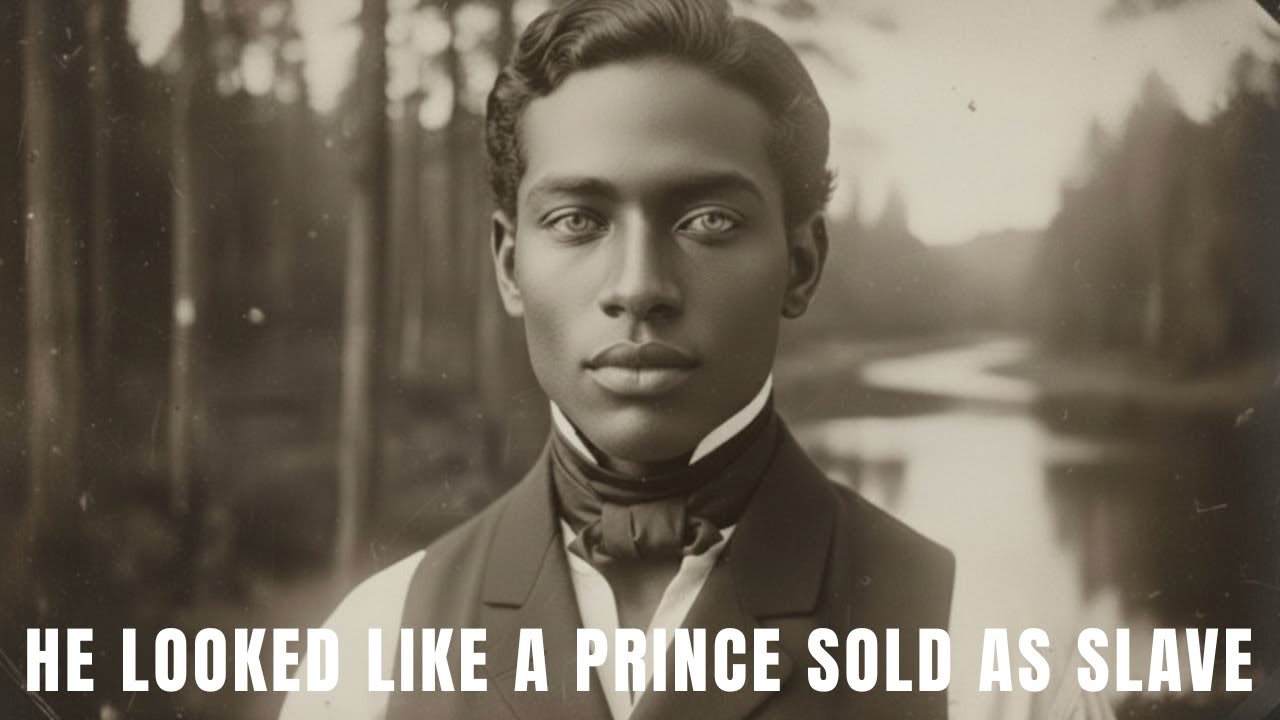

THE MAN WHO WAS TOO BEAUTIFUL TO BE SOLD

Richmond, Virginia — 1855

In the heart of 19th-century Richmond, where Shockoe Bottom’s slave market churned with cruelty and commerce, a single daguerreotype was made.

It was routine work.

Photographers sometimes recorded auction blocks as advertisements: a way for dealers to show their “stock” to distant buyers. Most plates were lost, thrown away, or melted down. Only one survived in the state archives with a label so plain it was almost insulting:

“Lot 77 — Richmond, 1855.”

No name.

No plantation.

No price.

Just a number.

For more than a century, it sat unnoticed. Historians catalogued the crates around it, transcribed receipts, counted shackles. They had seen thousands of images of enslaved men and women, and all of them followed the same visual language:

shoulders slumped

eyes downcast

faces set in numb endurance

But Lot 77 did not follow the rules.

In the photograph, a barefoot man stands on the auction platform.

He is shirtless. His wrists are bound. A chain runs down to his ankles.

And yet—

He stands upright, spine like a column, shoulders relaxed, chin lifted.

He looks directly into the camera.

Not with fear.

Not with rage.

But with a strange, serene composure.

As if nothing around him—nothing being done to him—could diminish what he was.

His face is beautiful.

Not handsome in the ordinary sense, not simply symmetrical, but striking, the kind of beauty that unsettles: cheekbones like carved marble, lips neither smiling nor grim, eyes that seem to hold a private knowledge.

Even in the dull, silvered plate, he appears to glow. The light clings to him.

It is the only auction photograph in which the subject looks like a portrait, not property.

And it raised a question no one could answer:

Who was he?

Records of the sale were missing. The auction ledger for that day had a gap: Lot 76, followed by Lot 78.

Lot 77 was simply absent.

No price.

No buyer.

No plantation destination.

In the entire system that catalogued human lives like livestock, his trail vanished.

Researchers assumed the photograph had been mislabeled. Or misfiled. Or perhaps he had died before the sale.

But in 1972, when the plate was enlarged for preservation, something was noticed for the first time.

Along the man’s ribs, just beneath his left pectoral muscle, ran a faint vertical line. Thin, straight, perfect. Not jagged like a whip scar. Not curved like a healing knife wound.

It looked constructed.

As though the torso had been opened and closed.

The archivist examining it, Dr. Esther Crowell, wrote in her notes:

“This is not an injury. It is anatomical. The flesh appears sutured.”

Sutured.

In 1855.

Forty years before sterile surgery. Fifty before internal anesthesia. Sixty before the first successful thoracic operation.

Impossible.

Unless the man had been altered somewhere else. By someone else.

The image was sent to medical historians.

One replied:

“This is not consistent with any medical practice of the period.

It is consistent with… experimentation.”

Another wrote, privately:

“This is not a scar.

It is a seam.”

Shockoe Bottom had a reputation.

People were bought and sold there every day. But sometimes, the auctioneer’s platform was used for other displays: curiosities, rare specimens, “exotic beings.”

Most were exaggerations.

This one was different.

Old diaries from Richmond mention a “strange man” sold there in the spring of 1855:

“A specimen”

“Too fine for labor”

“Not like other Negroes”

One merchant wrote:

“He stood like an emperor among men. A beautiful creature. No price was called. He was gone before the crowd could gather its wits.”

Gone.

No record.

No trace.

A rumor circulated later:

The auctioneer did not take bids.

Instead, he asked a question:

“Who among you wants perfection?”

The crowd laughed.

Then he revealed the man.

The laughter stopped.

The silence that followed was described as unnatural.

One witness, a clerk named Hartwell, later confessed in a letter:

“I felt shame. I felt awe. I felt fear that we had no right to touch such a being.”

Men who bought human beings every day—who beat them, branded them, broke them—could not raise a hand.

The price was irrelevant.

No one dared to claim ownership.

The auctioneer, panicked, ended the sale. Guards moved the man from the platform. No one saw where he was taken.

Some said he was put into a carriage.

Others said he was led away on foot.

A few said he simply vanished behind the warehouse.

By nightfall, he was gone.

For decades, Lot 77 became a ghost story among archivists.

Everyone had a different theory.

A West African royal, captured and sold. His posture, his calm, his beauty—they suggested nobility. Perhaps the seam was from a spear wound, long before captivity.

But no West African surgical technique of the period could produce a straight line like that.

In the late 19th century, Richmond spiritualists claimed he was not human at all.

An angel, briefly incarnate.

A fallen star.

Beauty as a punishment.

Ridiculous.

And yet…

The darkest theory was this:

He had been experimented on.

Some pointed to early anatomical societies in Philadelphia and Charleston. Others whispered about private medical rooms hidden behind plantation houses. Wealthy men with obsessions. Surgeons without ethics.

One document, unsigned, found in a physician’s papers from 1855, contained only a sentence:

“He was opened to see what lay within, and closed again when nothing could be improved.”

Legend holds that Lot 77 was not sold at all.

He was given.

Purchased privately by a man who did not attend the auction, who never came in person. The agent simply whispered to the auctioneer:

“He belongs to Dr. Templeton.”

Templeton was a physician of frightening reputation. A man who believed beauty was a form of divinity. A man who practiced surgery with tools of his own design.

Templeton’s notes were later burned. Only fragments survived.

One reads:

“The subject heals to perfection. No suppuration. No inflammation. As though the flesh remembers its original shape.”

Another:

“Pain does not trouble him.”

And finally:

“I cannot claim him. He is beyond ownership.”

Templeton died in 1859.

After his death, no trace of the man remained.

In the fall of 1860, a riverboat captain reported seeing a stranger walking along the James River, barefoot, shirtless, hair short, posture straight, unhurried.

When the captain approached to offer help, the man looked at him with the same serene expression as in the daguerreotype.

The captain wrote:

“I felt that if I touched him, I would be the one changed.”

The man said only one thing, in perfect English:

“Do not bind me.”

Then he stepped into the river and swam to the far bank with impossible ease.

No one ever saw him again.

The plate remains in a vault in Richmond.

Historians have argued for decades about how to classify it:

Ethnographic record?

Auction advertisement?

Medical photograph?

Anomaly?

No conclusion fits.

Visitors who view it behind glass often react the same way:

They fall silent.

They stand a long time.

Some weep without understanding why.

One viewer wrote in the guest log:

“I expected to see a slave.

But what I saw was a king.”

Another:

“Beauty is a rebellion. Perhaps that is why they feared him.”

Lot 77 was real.

He stood on an auction block in the deepest machinery of American slavery.

Bound.

Displayed.

Named only as a number.

Yet the photograph proves something that no ledger, no law, no price could erase:

He could not be owned.

There is a power in that image that unsettles the mind.

Not because of what it shows, but because of what it refuses to surrender:

Dignity in the face of dehumanization.

Serenity in the face of violence.

Beauty in a place built to break beauty.

No record, no receipt, no plantation memoir could contain him.

History tried to make him a commodity.

The camera made him immortal.

News

Nineteen Cents: The Woman They Tried to Erase

THE WOMAN SOLD FOR NINETEEN CENTS On the morning of November 7, 1849, the courthouse yard in Natchez was buzzing…

The Planter Who Married His Slave and Discovered She Was His Daughter

The Man Who Walked Into the Swamp and Was Never Seen Again The summer of 1839 was the kind that…

Seventeen Cents and a Kingdom of Ghosts

No one was ever supposed to read what was written on that slip of paper. It wasn’t a diary…

The Secret Buried in the Hills

When Don Aurelio Vargas rode back into his hacienda that March afternoon of 1858, the air above the fields…

The President, the Slave, and the Promise Made in Paris

Jefferson’s Hidden Family: The Story America Tried to Bury In September 1802, readers in Richmond, Virginia, unfolded their newspapers…

🕯️ “500 Years Locked Away: The Shocking Discovery Hidden Inside King Henry VIII’s Tomb Stuns the Entire World 😨📜”

⚰️ “Just Revealed: Archaeologists Break Open King Henry VIII’s Sealed Tomb—And What They Found Left Experts Trembling 😱👑” The decision…

End of content

No more pages to load