Preserved for Millennia: The Ancient Human Brain That Rewrites Archaeology

For thousands of years, one assumption in archaeology went almost entirely unquestioned: the human brain does not survive time.

Bone may endure.

Teeth may last.

Even skin can persist under extreme conditions.

But brain tissue — soft, fragile, and water-rich — was thought to vanish within days of death.

That belief has now been shattered.

Scientists have confirmed that an 8,000-year-old human brain was not only preserved, but preserved well enough for DNA to be successfully extracted.

The discovery has stunned archaeologists, geneticists, and neuroscientists alike, forcing a complete rethinking of what ancient remains can still tell us — and how much of human history may still be biologically accessible.

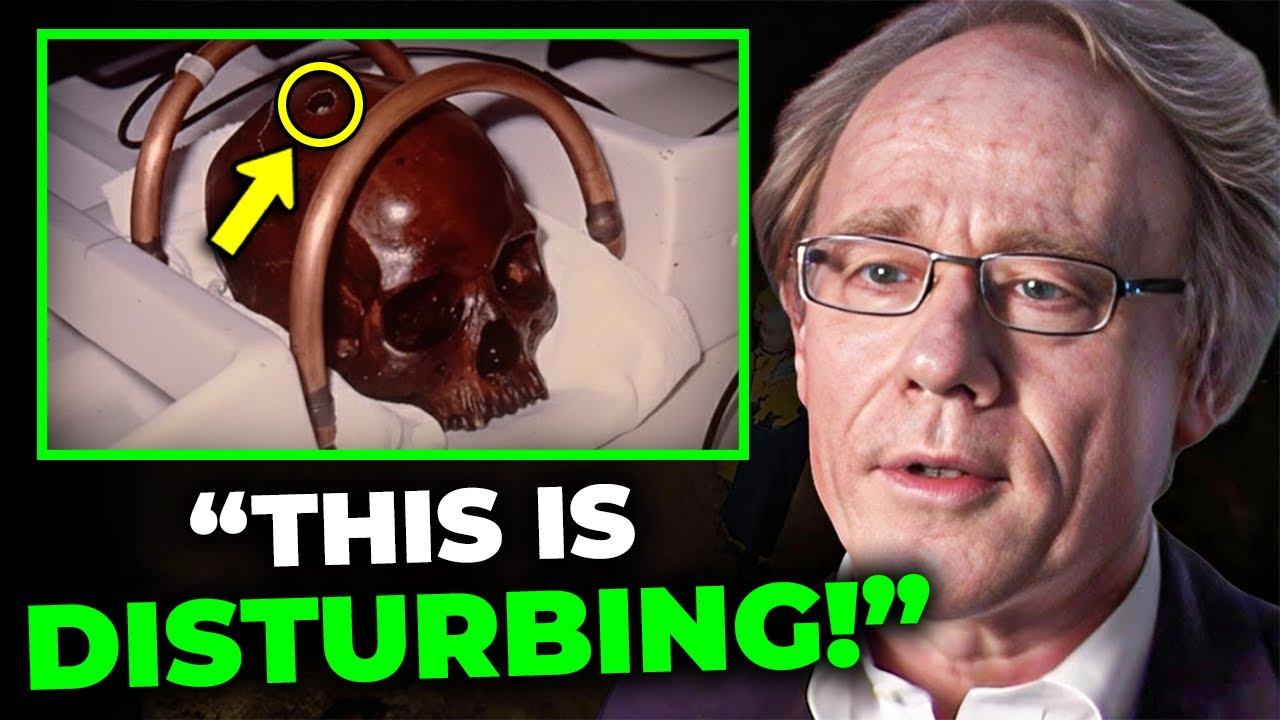

The story begins with a skull pulled from an ancient wetland burial site, dating back to the Mesolithic period.

At first glance, it appeared unremarkable — another fragment of a life long extinguished.

But when researchers examined the interior, they found something no one expected: dense, yellowish tissue still occupying the cranial cavity.

It was not sediment.

It was not mineral residue.

It was brain tissue.

Preserved.

For eight millennia.

What followed was a careful, almost hesitant investigation.

Scientists knew the stakes.

Claims of preserved brains are rare and often controversial.

Soft tissue usually decomposes rapidly unless frozen, mummified, or chemically altered.

Yet this brain had survived without ice, without embalming, and without intentional preservation.

The environment had done the impossible.

The remains were found in a waterlogged, oxygen-poor setting — conditions that dramatically slow microbial activity.

Over time, the brain tissue underwent a chemical transformation, becoming stabilized rather than decaying.

Proteins bound together.

Cellular structures collapsed inward instead of breaking apart.

What emerged was not a functioning brain, but a molecular fossil — fragile, but intact.

Then came the breakthrough.

Using modern clean-room protocols and ultra-sensitive sequencing techniques, scientists extracted ancient DNA directly from the preserved brain tissue.

Not from bone.

Not from teeth.

From the brain itself — a feat that was once considered nearly impossible.

The DNA was real.

It was endogenous.

And it was human.

Genetic analysis confirmed the individual lived roughly 8,000 years ago, during a time when hunter-gatherer societies were transitioning toward early agricultural life in parts of Europe.

The genetic markers aligned with known Mesolithic populations, but the implications went far beyond ancestry.

For the first time, researchers could directly study ancient neural tissue at a molecular level.

That changes everything.

Until now, knowledge of ancient brains came entirely from skull shape and indirect inference.

Intelligence, cognition, neurological health — all were guessed through bone.

This preserved brain offers something radically different: biochemical insight into how ancient human brains were structured, protected, and potentially how they aged.

Early analysis suggests that certain proteins within the brain tissue became unusually stable shortly after death, forming a natural preservative network.

This process may explain why brains — under very specific conditions — can survive for thousands of years without disintegrating.

And that realization has opened a disturbing and exciting possibility.

If one brain could survive, others might have too.

Archaeologists are now reevaluating wetland burials, peat bogs, and submerged sites across the world.

Places once thought to preserve only bone may be quietly holding intact neural tissue — undiscovered simply because no one expected it to be there.

The implications extend beyond archaeology.

Neuroscientists are fascinated by the molecular resilience of the tissue.

Understanding how proteins locked into stable formations could influence modern research into neurodegenerative disease, preservation of neural samples, and even long-term data storage using biological materials.

Historians are equally unsettled.

This brain belonged to a person who lived before writing, before cities, before recorded memory.

And yet, part of their most intimate biological identity — the organ that held their thoughts, fears, and experiences — endured long enough to be studied by scientists in the 21st century.

It collapses the emotional distance between past and present.

The discovery also raises uncomfortable ethical questions.

At what point does a biological relic become more than an object? This was not just DNA.

It was once a mind.

Researchers have proceeded with caution, emphasizing respect and minimal destruction of the tissue.

Still, the line between study and intrusion feels thinner when the material is this personal.

Critics have urged restraint, warning against sensationalism.

They are right to do so.

The DNA cannot reconstruct memories.

It cannot tell us what the individual thought or believed.

But it can tell us how ancient human biology functioned — and that knowledge has been lost for most of our species’ existence.

This preserved brain represents a bridge.

A bridge between prehistory and modern science.

Between flesh and data.

Between a life lived in silence and a world now listening.

The most haunting part of the discovery is its randomness.

The brain survived not because of intention, but because of circumstance.

A particular burial.

A specific environment.

A precise chemical balance.

Human history is full of moments like this — where chance decides what endures and what vanishes forever.

For centuries, we assumed the brain always vanished.

We were wrong.

And now that we know it can survive, the past suddenly feels far closer — and far more alive — than we ever imagined.

News

AI Analyzed Every Prayer in the Bible — and the Pattern It Found Changes Everything

What an AI Discovered About Biblical Prayer Is Making Believers Rethink Faith For thousands of years, prayers in the Bible…

A Nuclear City Beneath the Ice: Scientists Rediscover a Cold War Secret in Greenland

Buried for Decades: Radar Reveals a Forgotten Nuclear Base Under Greenland For decades, the ice of Greenland was believed to…

Tesla’s California Future in Doubt as Musk Signals Major Factory Pullback

Sacramento on Edge After Elon Musk Hints at Shutting Down Tesla’s California Operations Shockwaves rippled through California’s political and economic…

Astronomers Watched a Meteor Strike the Moon—Live, in Real Time

A Sudden Flash on the Moon Shocked Observers Worldwide In December 2025, astronomers watching the night sky witnessed something so…

The Cascades Are Alive: Why Experts Are Issuing a Rare Warning

Beneath Oregon, Pressure Is Building: What Volcanologists Are Watching Now A growing unease is rippling through the Pacific Northwest as…

The Dark Codes Hidden in Göbekli Tepe’s 12,000-Year-Old Pillars

AI Analysis of Göbekli Tepe Reveals Patterns No One Expected For decades, Göbekli Tepe has unsettled everything archaeologists thought…

End of content

No more pages to load