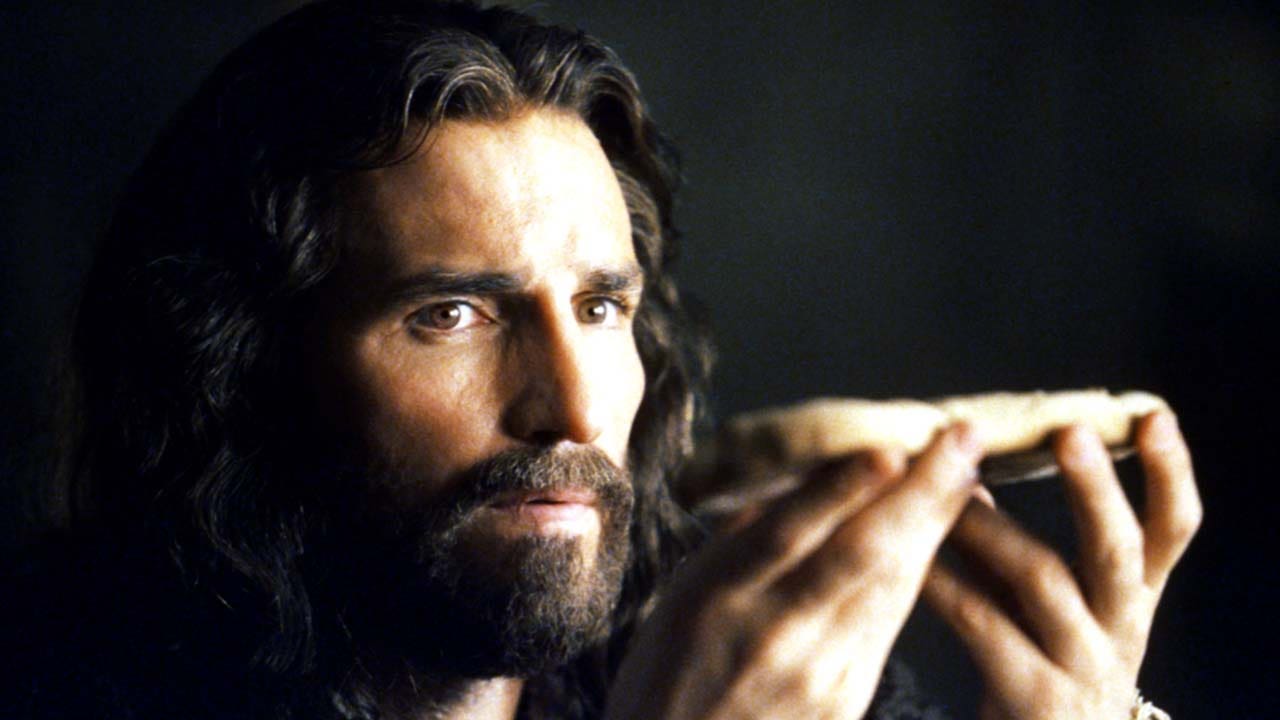

Mel Gibson Ignites Global Firestorm After Claiming Ethiopia’s Ancient Bible Reveals a Side of Jesus the World Was Never Meant to See

In a claim that has sent ripples through religious circles and ignited fierce debate online, Mel Gibson has drawn attention to what he describes as an extraordinary portrait of Jesus found within the Ethiopian Bible—a portrayal that, he insists, challenges nearly everything the modern world thinks it knows about the central figure of Christianity.

The statement, delivered with the gravity Gibson has often brought to faith-related conversations, did not arrive as a casual remark.

It landed like a spark near dry tinder, instantly reigniting long-simmering questions about ancient texts, lost traditions, and who gets to decide which stories survive history.

According to Gibson, the Ethiopian Christian tradition preserves scriptures that are far older and far more expansive than those recognized in the Western biblical canon.

While most Christians are familiar with a Bible of 66 books, the Ethiopian Orthodox tradition maintains a canon that exceeds 80 texts, some of which have never been fully translated into modern languages.

Gibson argues that within these pages lies a depiction of Jesus that is not merely symbolic or poetic, but startlingly detailed—describing his character, teachings, inner conflicts, and daily life in ways absent from the Gospels taught in churches today.

What makes the claim so provocative is not simply the existence of additional texts, but what they suggest.

Gibson alluded to narratives that emphasize Jesus as a deeply human figure: one who experiences doubt as sharply as devotion, who grapples with fear before moments of resolve, and whose spiritual authority is portrayed as something earned through struggle rather than bestowed without cost.

This Jesus, according to the Ethiopian tradition, is not softened for comfort nor simplified for doctrine.

He is complex, unsettling, and intensely present in the physical world.

Scholars have long acknowledged that Ethiopia holds one of the oldest continuous Christian traditions on Earth, dating back to at least the fourth century.

Its scriptures were preserved in Ge’ez, a classical language that insulated them from many of the edits, omissions, and theological battles that shaped the Bible in Europe and the Middle East.

For centuries, these manuscripts remained largely inaccessible to outsiders, stored in monasteries perched on cliffs, hidden in desert churches, and guarded by religious authorities wary of foreign interpretation.

Gibson’s comments have reopened an uncomfortable conversation: if these texts have existed for more than a millennium, why are they absent from mainstream Christian teaching? Critics argue that the formation of the Western canon was as much a political process as a spiritual one, shaped by councils, emperors, and institutional priorities.

Supporters of Gibson’s view suggest that alternative portrayals of Jesus—especially those that resist clean theological packaging—may have been sidelined because they complicated emerging doctrines.

The reaction has been swift and polarized.

Some theologians caution against sensationalism, noting that ancient texts often reflect the spiritual culture of their communities rather than verifiable historical detail.

They argue that differences in emphasis do not necessarily invalidate the canonical Gospels.

Others, however, see the Ethiopian scriptures as a rare window into early Christian diversity, proof that the story of Jesus was never singular, but woven from many voices that later power structures narrowed into one authorized narrative.

Online, the debate has turned combustible.

Believers hungry for a more intimate, less institutional faith have embraced the idea that something profound has been hidden in plain sight.

Skeptics accuse Gibson of romanticizing obscure texts to provoke controversy, pointing out that he has long been drawn to interpretations of Christianity that emphasize suffering, sacrifice, and moral confrontation.

Yet even critics concede one point: the Ethiopian tradition is real, ancient, and insufficiently explored.

What truly unsettles many observers is the implication that faith itself may be incomplete without these forgotten voices.

If the Ethiopian scriptures indeed portray Jesus with greater psychological depth—showing moments of hesitation, anger, and loneliness—then the familiar image taught to billions may be only a partial reflection.

Such a realization does not merely challenge theology; it challenges comfort.

A Jesus who doubts is harder to idealize.

A Jesus who struggles is harder to control.

As interest surges, calls are growing for comprehensive, transparent translations of the Ethiopian canon by international teams of linguists and historians.

Some monasteries have begun cautiously cooperating with researchers, while others remain resistant, citing centuries of exploitation and misrepresentation by outsiders.

The tension underscores a larger issue: who owns sacred history, and who has the right to interpret it?

For now, Gibson’s statement has accomplished one undeniable thing—it has forced a global audience to look toward Ethiopia, toward manuscripts written in fading ink on ancient parchment, and toward the possibility that the story of Jesus is far richer and far more unsettling than most have been taught.

Whether these texts will ultimately reshape mainstream understanding or remain a source of controversy is uncertain.

But the silence surrounding them has been broken, and once questions of this magnitude are asked, they rarely fade quietly.

If the Ethiopian scriptures do reveal a Jesus “not what you think,” then the shock is not that such texts exist, but that the world is only now beginning to listen.

News

🌴 Population Shift Shakes the Golden State: What California’s Migration Numbers Are Signaling

📉 Hundreds of Thousands Depart: The Debate Growing Around California’s Changing Population California has long stood as a symbol…

🌴 Where Champions Recharge: The Design and Details Behind a Golf Icon’s Private Retreat

🏌️ Inside the Gates: A Look at the Precision, Privacy, and Power of Tiger Woods’ Jupiter Island Estate On…

⚠️ A 155-Year Chapter Shifts: Business Decision Ignites Questions About Minnesota’s Future

🌎 Jobs, Growth, and Identity: Why One Company’s Move Is Stirring Big Reactions For more than a century and…

🐍 Nature Fights Back: Florida’s Unusual Predator Plan Sparks New Wildlife Debate

🌿 From Mocked to Monitored: The Controversial Strategy Targeting Invasive Snakes Florida’s battle with invasive wildlife has produced many…

🔍 Ancient Symbols, Modern Tech: What 3D Imaging Is Uncovering Beneath History’s Oldest Monument

⏳ Before the Pyramids: Advanced Scans Expose Hidden Features of a Prehistoric Mystery High on a windswept hill in…

🕳️ Secrets Beneath the Rock: Camera Probe Inside Alcatraz Tunnel Sparks Chilling Questions

🎥 Into the Forbidden Passage: What a Camera Found Under Alcatraz Is Fueling Intense Debate Alcatraz Island has…

End of content

No more pages to load