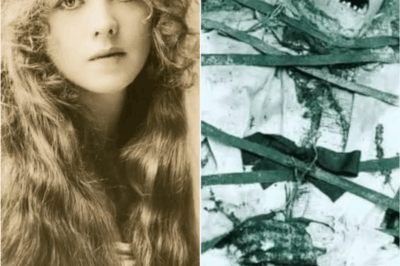

✡️ “The Face the Nazis Couldn’t Erase: The Five Days That Stole Aron Löwi’s Life — But Not His Humanity 💔🕯️”

Before the trains and the tattoos, before the gas chambers and the silence, there was a man named Aron.

He sold goods, shook hands, shared meals with his neighbors.

He wasn’t a soldier or a rebel — he was ordinary, and that’s what makes his story so devastating.

Because in 1942, being ordinary and Jewish in occupied Poland was a death sentence.

The Nazis came to Zator with their usual efficiency — lists, orders, and deadlines.

Jewish families were rounded up in public squares, told to bring only what they could carry.

Some believed they were being “resettled.

” Others knew the truth but had nowhere to run.

For Aron, at 62, the journey would be short, brutal, and final.

The train that took him to Auschwitz was packed with hundreds like him — men, women, and children pressed together in cattle cars, gasping for air, suffocating in the darkness.

The ride lasted hours, maybe days.

No one spoke much.

They didn’t need to.

The fear was its own language.

When the doors opened, what awaited them wasn’t a camp.

It was a machine built to destroy the idea of a person.

At the gates, guards shouted.

Dogs barked.

The words “Arbeit Macht Frei” — Work sets you free — hung above them like a cruel joke.

Aron was stripped, shaved, and photographed — the moment his humanity was officially stripped away.

His intake photo still exists: a gaunt man staring straight into the lens, eyes that seem to plead and defy all at once.

You can see the pain already in progress — bruises, cuts, starvation.

The Nazis documented everything, even their cruelty, because control wasn’t enough.

They needed proof of it.

Pinned to Aron’s striped uniform were symbols meant to brand him forever.

The yellow Star of David for being Jewish.

The red inverted triangle for being a political prisoner — perhaps for speaking out, perhaps for nothing at all.

Around him, other prisoners bore their own marks: green for “criminals,” pink for “homosexuals,” black for “asocial.

” It was a grotesque color-coded taxonomy of hate, each triangle a sentence of slow death.

For the Nazis, numbers replaced names, symbols replaced souls.

To call someone by their name was to acknowledge their humanity — and that, above all, was forbidden.

Aron Löwi ceased to exist the moment they inked 26406 onto his arm.

The records show that he entered Auschwitz on March 5th, 1942.

And on March 10th, just five days later, his life ended.

No explanation.No record of execution.No burial.

In the cold arithmetic of genocide, his existence was reduced to a date of arrival and a date of disappearance.

Everything in between — the pain, the fear, the thoughts of home — vanished into smoke.Five days.

That was all the time it took to erase a lifetime.

When researchers later uncovered his photograph, they described the image as “unbearably human.

” His face wasn’t defiant, but it wasn’t broken either.

It was something in between — the look of a man who knows he will die, but refuses to let his eyes look away from history.

That photograph, taken by the very system that sought to destroy him, has become his resistance.

The Nazis turned him into a number; now, his number is a reminder that every statistic had a heartbeat.

Aron’s death is not unique — and that’s the tragedy.

He was one of over a million who perished in Auschwitz, each with their own name, family, and dreams.

Yet his story, brief as it was, reminds us why memory matters.

The Holocaust wasn’t just the murder of bodies — it was the attempted murder of memory.

And every time we say his name, we deny the Nazis their final victory.

What makes Aron’s story especially haunting is how complete the erasure almost was.

No relatives survived to claim his remains.

No grave marks his passing.

If not for one photograph and a few lines in a Nazi ledger, the world would have never known he existed.

And yet, that’s what makes his survival — through image — so powerful.

In that photo, his gaze crosses decades.

It finds us.

It asks us to remember.

Historians have long said that photographs from Auschwitz are both unbearable and essential.

They expose the systematic process of dehumanization — the shaved heads, the hollow eyes, the forced poses.

Each face is a rebellion against invisibility.

Aron’s especially so.

Because though his captors meant that image to strip him of identity, it does the opposite.

It immortalizes it.

When the Nazis documented their victims, they didn’t realize they were preserving evidence — evidence that would one day expose their crimes.

They wanted to erase individuality, but instead, they created an eternal archive of defiance.

Every photograph, every tattooed number, every scrap of paper that survived is a whisper from the ashes: We were here.

Aron’s number — 26406 — might seem meaningless to someone flipping through records.

But look closer, and you’ll see it’s written in a trembling hand, beside the word “Jude.

” It’s not just ink on paper.

It’s the last trace of a human life, one the world almost forgot.

There’s a cruel poetry in how memory works.

The Nazis built their empire on annihilation, on fire and silence.

Yet in the end, silence is what betrays them.

Because the very system that tried to erase Aron ensured he would never truly disappear.

His photo circulates today in archives, exhibitions, and on screens — seen by millions.

Each viewer becomes a witness, and with every glance, Aron lives again.

He doesn’t speak, but his face tells the story: the bruises, the exhaustion, the resignation, the faint spark of defiance.

It’s a story not just of one man, but of humanity itself — our capacity for cruelty, and our stubborn will to remember.

Five days in Auschwitz.

Sixty-two years of life.

One photograph that outlived them all.

In the end, the Nazis failed at the one thing they wanted most: to make him vanish.

Aron Löwi’s face remains — unflinching, undeniable.

A fragment of light that even history’s darkest night couldn’t consume.

Because memory, like truth, doesn’t dissolve.

It burns.

And in that burning, he is eternal.

News

🏔️ “Frozen at the Roof of the World: The Last Breath of Hannelore Schmatz — The Woman Who Died Staring at the Sky ❄️😢”

“She Conquered Everest — Then It Took Her Soul: The Terrifying True Story of Hannelore Schmatz’s Final Breath 🏔️🕯️” …

😨 “They Tried to Kill Her Six Times — and Failed: The Chilling Curse of Anna Maria, the Vampire Who Defied Death 💀🔥”

⚰️ “The Woman Who Wouldn’t Die: Inside the Terrifying Legend of Anna Maria, the Undying Witch of the Carpathians 🕯️🩸”…

“Under the Dirt Lies a Secret: The Chilling Discoveries Inside the Alleged Noah’s Ark Site in Turkey 🧬🌋”

“Inside the Ark No One Believed Could Exist — What We Found in Turkey Is Bone-Chilling 🔍💧” High in…

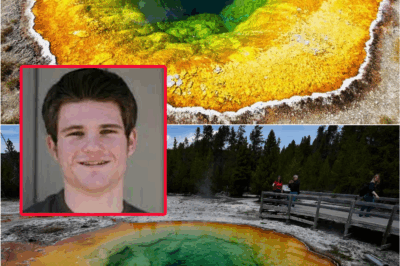

⚡ “He Fell Into the Earth’s Mouth: Yellowstone Incident That Shook the Nation 🌋😨”

“Melted by the Earth Itself: The Unimaginable Fate of a Young Man at Yellowstone’s Deadliest Hot Spring 🌡️💀” Yellowstone…

⚡ “The Moment Everything Went Wrong: Inside MrBeast’s Critical On-Set Accident That Left Fans in Shock 😨🎥”

😱 “MrBeast’s Most Dangerous Challenge Yet Ends in Chaos: The Terrifying On-Set Incident That Shook YouTube 🌪️📸” MrBeast isn’t just…

⚡ “What Really Happened to Swamp People: The Pain Behind the Bayou’s Biggest Stars 🌾😔”

“From Glory to Grief: The Untold Truth About the Collapse of Swamp People — It’ll Break Your Heart 💥🐊” …

End of content

No more pages to load