Not the Resurrection You Were Taught: Ethiopia’s Ancient Manuscript Rewrites Christianity’s Most Sacred Moment

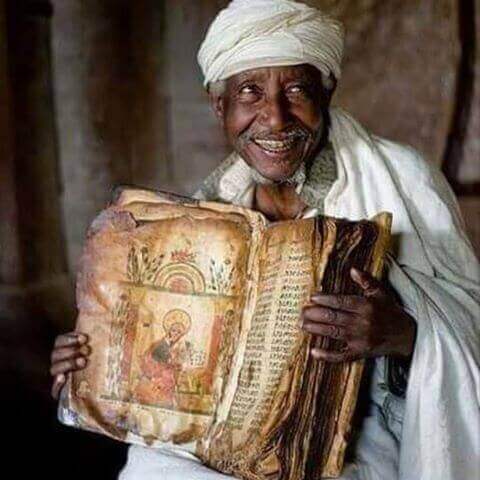

For centuries, the most guarded manuscripts in Christianity were not hidden in the Vatican, nor buried beneath European cathedrals, but preserved in silence by Ethiopian monks who believed some knowledge was too powerful to release before its time.

Now, that silence has been broken.

In a move that has stunned historians, theologians, and believers alike, monks affiliated with the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church have released a newly translated Resurrection passage from an ancient Ge’ez manuscript—one that presents events so unfamiliar, so unsettling, that it is already forcing scholars to reconsider what they thought they knew about the most sacred moment in Christian faith.

The passage comes from a text long referenced in Ethiopian tradition but rarely studied outside it, preserved in monasteries where access is restricted and translation requires not only linguistic mastery but spiritual authorization.

Written in classical Ge’ez, the manuscript was believed to date back to the earliest centuries of Christianity, possibly drawing from traditions that existed before the New Testament canon was formally sealed.

Until now, fragments were known.

The full Resurrection account was not.

What the monks have released does not contradict the Resurrection—but it reframes it in ways that are deeply unsettling to modern theology.

According to the translated passage, the Resurrection was not a quiet miracle witnessed only by a few women at dawn.

It was a cosmic event that unfolded across realms—earth, heaven, and the domain of the dead—simultaneously.

The text describes the moment Christ rose not as peaceful, but as terrifying.

The earth is said to tremble violently, not merely as a sign, but as a reaction.

Darkness does not lift gently; it fractures.

Time itself is described as “hesitating,” as if creation momentarily failed to understand what was happening.

Most shocking is how the passage treats the moments before the Resurrection.

Unlike the canonical Gospels, which are largely silent between the crucifixion and the empty tomb, this Ethiopian text dwells intensely on that interval.

It describes Christ descending into the realm of the dead, not symbolically, but deliberately—entering a place portrayed as organized, ruled, and resistant.

The manuscript speaks of gates, watchers, and a confrontation that is neither metaphor nor parable.

Death, in this account, is not passive.

It is challenged.

The Resurrection, then, is not simply Christ returning to life—it is Christ returning changed.

The text states that when Christ rises, his presence is unbearable to those who witness it.

Angels recoil.

Guards collapse in terror.

Even the faithful struggle to comprehend what they see.

His body bears wounds, but it is no longer bound by matter.

He casts no ordinary shadow.

His voice is described as layered, as if more than one realm speaks through it.

This is not the gentle figure of Renaissance art.

This is something closer to awe mixed with fear.

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of the passage is its portrayal of the disciples.

Rather than immediate belief and joy, they respond with confusion, dread, and doubt that borders on panic.

The manuscript suggests that faith was not born instantly—it was wrestled into existence.

Belief, in this telling, comes only after fear, denial, and confrontation with something too vast to absorb.

Why has this passage been hidden for so long?

According to Ethiopian tradition, certain texts were withheld not because they were false, but because they were considered spiritually dangerous if misunderstood.

The monks involved in the release stated that the passage was never meant to soften faith, but to shake it.

In their view, much of modern Christianity has reduced the Resurrection to comfort—while the earliest believers experienced it as upheaval.

The release has considerabally ignited debate worldwide.

Some theologians argue that the text reflects symbolic theology rather than historical detail, shaped by early Christian mysticism.

Others counter that dismissing it too quickly mirrors the very process by which non-Western traditions were sidelined in the formation of the biblical canon.

Ethiopia, after all, maintained a continuous Christian identity while Europe was still defining doctrine through councils and imperial power.

What cannot be ignored is the manuscript’s age and preservation.

Linguistic analysis confirms archaic Ge’ez structures consistent with early Christian texts.

References within the passage align with beliefs recorded in Eastern and African Christianity long before they were marginalized in Western theology.

Scholars note striking parallels between this Resurrection account and ancient liturgies, iconography, and oral traditions that survived only outside Europe.

The implications are enormous.

If this passage reflects how early Christians understood the Resurrection, then the event was not meant to reassure—it was meant to transform through fear, awe, and surrender.

The Resurrection was not an ending, but a rupture in reality.

Salvation, in this context, is not gentle acceptance but radical change.

Public reaction has been explosive.

Some believers describe the text as deeply moving, saying it restores a sense of sacred mystery lost in modern faith.

Others feel disturbed, even betrayed, by how unfamiliar the Resurrection feels in this account.

Skeptics accuse the monks of releasing the text at a time of global uncertainty to provoke spiritual destabilization.

The monks themselves reject that claim, stating simply: “The time is now because the world no longer fears God—it fears meaninglessness.

”

Whether this passage will ever be accepted beyond academic and spiritual circles remains uncertain.

But one thing is already clear: the Resurrection may be far bigger, stranger, and more terrifying than the version most people were taught.

If the Ethiopian monks are right, then Christianity’s central miracle was never meant to feel safe.

It was meant to undo the world—and remake it.

And now, after centuries of silence, that forgotten voice is finally being heard.

News

🌴 Population Shift Shakes the Golden State: What California’s Migration Numbers Are Signaling

📉 Hundreds of Thousands Depart: The Debate Growing Around California’s Changing Population California has long stood as a symbol…

🌴 Where Champions Recharge: The Design and Details Behind a Golf Icon’s Private Retreat

🏌️ Inside the Gates: A Look at the Precision, Privacy, and Power of Tiger Woods’ Jupiter Island Estate On…

⚠️ A 155-Year Chapter Shifts: Business Decision Ignites Questions About Minnesota’s Future

🌎 Jobs, Growth, and Identity: Why One Company’s Move Is Stirring Big Reactions For more than a century and…

🐍 Nature Fights Back: Florida’s Unusual Predator Plan Sparks New Wildlife Debate

🌿 From Mocked to Monitored: The Controversial Strategy Targeting Invasive Snakes Florida’s battle with invasive wildlife has produced many…

🔍 Ancient Symbols, Modern Tech: What 3D Imaging Is Uncovering Beneath History’s Oldest Monument

⏳ Before the Pyramids: Advanced Scans Expose Hidden Features of a Prehistoric Mystery High on a windswept hill in…

🕳️ Secrets Beneath the Rock: Camera Probe Inside Alcatraz Tunnel Sparks Chilling Questions

🎥 Into the Forbidden Passage: What a Camera Found Under Alcatraz Is Fueling Intense Debate Alcatraz Island has…

End of content

No more pages to load