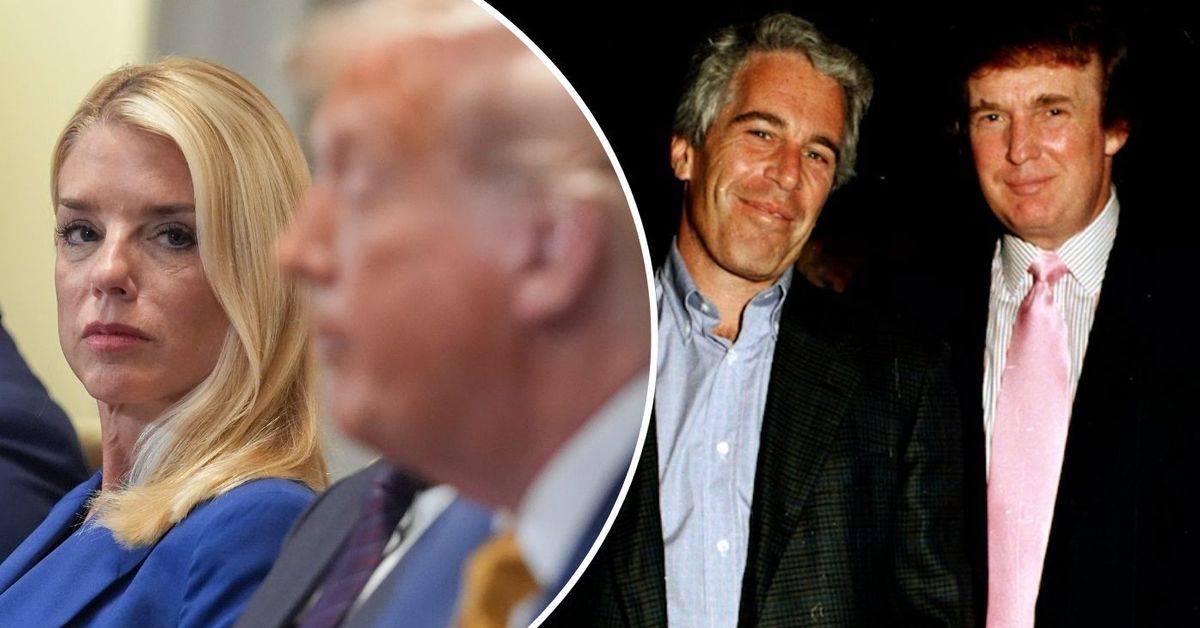

💥 Convicting Trump on Epstein Evidence Looks Simple on Paper — But the Hidden Forces Blocking It Will Leave You Speechless and Furious 😡⚡️

Start with the basics: the connection between Donald Trump and Jeffrey Epstein is not a conspiracy theory invented yesterday — it’s been mapped in photographs, society pages and official records for years, and reporters have compiled timelines showing social ties, shared events and travel overlaps that create a frame for further inquiry.

From a prosecutorial perspective, three kinds of evidence tend to move a case forward quickly: witness testimony that names a suspect, documentary proof that places the suspect at critical times and places, and corroborating records (payments, communications, or corroborating eyewitness statements) that close the loop.

On face value, the Epstein corpus contains elements of all three: testimony unsealed in civil suits and criminal trials, photographs placing public figures at Epstein-connected events, and flight and visitor logs that can place names on planes, properties and private jets.

That’s why many observers say — in blunt terms — that convicting someone tied to Epstein “should be easy.

” The raw ingredients exist.

Yet the jump from “raw ingredients” to “guilty verdict” is enormous, and that’s where complexity explodes.

The first and most consequential barrier is burden of proof.

Criminal prosecutions require proof beyond a reasonable doubt — not a preponderance of evidence, and certainly not a media narrative.

Memories fade, witnesses are reluctant, and the core alleged victims in the Epstein orbit often fear publicity, retribution or reliving trauma, making robust, courtroom-ready testimony harder to secure than scandal-hungry headlines suggest.

Prosecutors will not risk a high-profile trial on shaky testimony no matter how compelling the surrounding rumor mill is.

The second barrier is the death of Jeffrey Epstein himself.

Epstein’s suicide in 2019 destroyed the possibility of his direct testimony and any plea bargains that could have unlocked cooperator testimony or documentary revelations.

The disappearance of that central figure removed the easiest path to leverage — turning one defendant’s cooperation into a domino effect of indictments.

Third, the legal record shows active gatekeeping around what investigators have actually found.

Government statements and internal memos — and the public posture of the Department of Justice in particular — have repeatedly pushed back against the sensationalist idea of a single “client list” that names famous figures being held in secret.

In multiple public explanations and releases, DOJ officials have said they didn’t find evidence of a tidy, comprehensive “blackmail ledger” listing clients in a criminal sense — a conclusion that undercuts the simple narrative that prosecutors are merely refusing to act on an obvious list.

That official finding is a major reason why prosecutors have not filed sweeping charges based on a mythical list.

Fourth, political dynamics matter more than many like to admit.

Investigations that touch powerful people inevitably collide with political calculation: open an indictment and a trial risks exposing judicial processes to campaign-season manipulation, partisan backlash and lawsuits; close the file and you face accusations of cover-up.

In the past year, actions such as the executive branch’s decisions on releasing records, firings within the DOJ, and congressional subpoenas have all created the perception — and sometimes the reality — of political interference that complicates a clean, apolitical criminal referral.

Recent reporting and congressional disclosures about withheld records and contested memos underscore that the decision to prosecute is no longer purely legal; it’s also intensely political.

Fifth, practical evidentiary problems persist.

Paper trails are messy: flight logs show names and initials but not intent; guestbooks show a signature but not actions; letters and photographs show proximity but not criminal conduct.

In some instances, records are sealed by grand jury rules or tied to plea agreements that limit their public use.

Prosecutors must build narratives that a judge and jury can accept — and legal teams defending high-profile targets can and do exploit every gap in the paper trail to raise reasonable doubts.

Sixth, strategy differs between jurisdictions.

Local prosecutors in Florida, New York, and federal prosecutors in Manhattan and elsewhere have different resources, witness access and legal theories.

Coordinating charges across jurisdictions is logistically and legally difficult.

The death of key witness opportunities and the transnational movement of documents add logistical friction.

Seventh, there is the real-world risk calculus: prosecutors and career lawyers worry about reputational and institutional harm from failed prosecutions.

A high-stakes, widely publicized case that ends in acquittal can chill future victims from coming forward and can undermine the very idea of accountability the investigators are trying to preserve.

That risk produces an understandable — if politically unpopular — bias toward caution.

Finally, there are tactical choices about publicity.

Leaking information and stoking public outrage can produce pressure, but it can also contaminate a jury pool or tip off potential targets, leading to destroyed evidence.

Smart prosecutors often weigh the benefits of secrecy against the benefits of public pressure — and secrecy frequently wins.

After all this, why does the “should-be-easy” narrative persist? Because people see photos and flight logs and feel an intuition that proximity equals complicity.

They see a government that delays, classifies or disputes and infer malfeasance.

They sense a double standard when wealthy or powerful people appear to escape accountability.

Those feelings amplify when the political class uses the records as bargaining chips, or when agencies issue ambiguous denials that sound like cover-ups.

The truth sits between two instincts: outrage at apparent privilege and a legal system built on burdens and protections designed to avoid wrongful convictions.

What would change the calculus? New victims willing to testify under oath, provable contemporaneous records directly linking alleged acts to a suspect, credible cooperating witnesses from Epstein’s inner circle, or legal breakthroughs that make existing records admissible without violating grand jury rules.

Any of those could convert the messy dossier into a prosecutable file.

Until then, the gap remains: a dossier that looks prosecutorial in social media snapshots, but in legal reality is full of evidentiary potholes, political landmines and institutional hesitancy.

The result is a public that believes conviction should be simple, and a justice system that — for better and worse — insists it’s more complicated than headlines.

News

🌙🕵️♂️ “The Haunting Truth Willie Edwards Never Wanted Fans To See On Swamp People”

🐊💔 “Behind The Gators: Willie Edwards’ Secret Struggle That Shattered The Swamp People Illusion” For years, Swamp People sold…

🕯️🥀 “What Happened To Paul Anka? The Hauntingly Sad Decline Of A Music Icon”

🎤: The Lonely Reality Behind The Legend They Don’t Want Fans To See” The tale of Paul Anka at 84…

😱🌊 “What Spielberg Just Confessed About Jaws Will Change The Way You See The Movie Forever”

🕵️♂️🦈 “Behind The Shark’s Shadow: Spielberg’s Chilling Revelation About Jaws That Fans Missed For Nearly 50 Years” When Spielberg…

🥶💔 “Behind The Silence In Alaska: The Moment That Shattered The Last Frontier Crew Forever”

🌌🚨 “Frozen Truth: The Chilling Collapse Of The Alaska: The Last Frontier Cast That Nobody Saw Coming” The trAlaska: The…

🕵️♂️🌲 “Sue Aikens’ Warnings Ignored — The Chilling Truth About the Arctic Survivor Finally Surfaces” ⚡🌨️

🚨🌌 “The Dark Side of Sue Aikens: What Life Below Zero Never Showed Us” 🔥💔 Sue Aikens was never supposed…

🚨🔥 “The Dark Truth of Heimo Korth: The Last Alaskans’ Most Mysterious Figure Finally Exposed” 🌌💔

🕵️♂️🌪️ “Heimo Korth’s Warning Signs Ignored — The Last Alaskans’ Legend Hides a Story No One Wanted Told” ❄️⚡ …

End of content

No more pages to load