Beneath Benin City Lies One of the Largest Ancient Structures on Earth — And History Got It Wrong

For centuries, Benin City was spoken of with admiration by early European visitors and then quietly misunderstood by history.

Travelers described massive walls and deep moats stretching beyond the horizon, feats so vast they sounded exaggerated to later generations.

Over time, colonial narratives reduced those accounts to myth, insisting Africa’s urban past could not have produced infrastructure on such a scale.

Now, beneath the modern city and surrounding forests, archaeologists have uncovered evidence that forces a permanent rewrite of that story.

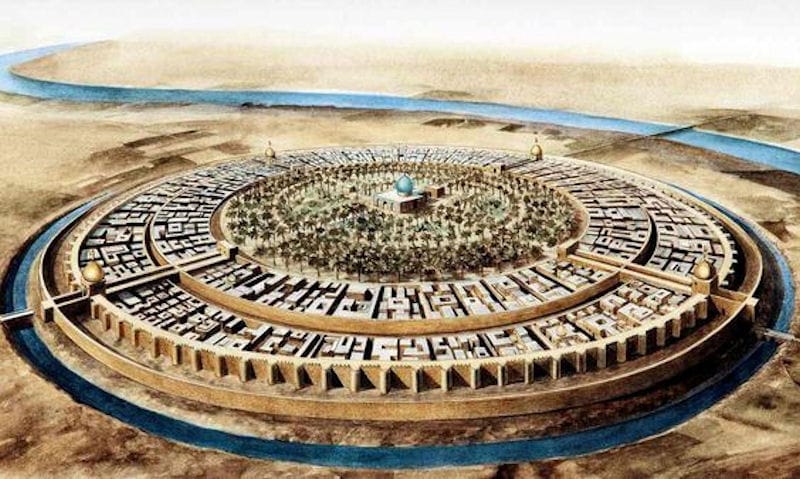

What they found was not a single monument or buried palace, but an immense, interconnected system of earthworks—trenches, embankments, and roads—constructed with a precision and ambition that rivals the greatest engineering projects of the ancient world.

Known collectively as the Benin Earthworks, these structures were once thought to be fragmented or symbolic.

New surveys reveal they were anything but.

Using modern mapping techniques, including satellite imagery, soil analysis, and ground surveys, researchers confirmed that the earthworks formed a vast network surrounding and linking communities across what is now southern Nigeria.

The scale is staggering.

When measured end to end, the system extends for thousands of kilometers, making it one of the largest human-made earth structures ever created—larger in total length than the Great Wall of China.

What stunned archaeologists was not just the size, but the organization.

The earthworks were not randomlydug.

They followed consistent geometric patterns, with straight segments, sharp angles, and carefully calculated curves that adapted to terrain.

The moats were deep and defensive, the embankments tall and reinforced, suggesting centralized planning and coordinated labor over generations.

This was not the work of a scattered society.

It was the signature of a powerful state.

Radiocarbon dating places much of the construction between the 9th and 15th centuries, long before European contact.

That timeline dismantles the idea that large-scale urban planning arrived in the region from the outside.

Benin was already a thriving, sophisticated kingdom when much of Europe was still struggling through fragmented feudal systems.

Even more transformative is what the discoveries reveal about governance.

Beneath Benin City, archaeologists identified layered occupation zones indicating long-term urban continuity rather than collapse and replacement.

Streets were planned.

Neighborhoods were organized.

Defensive lines were expanded outward as the population grew.

This suggests a stable political authority capable of mobilizing resources, enforcing design standards, and maintaining infrastructure across centuries.

In other words, this was not a temporary city.

It was a civilization that planned for permanence.

The implications extend far beyond Nigeria.

For decades, African history was framed as largely oral, local, and limited in scale.

Monumental architecture was treated as an exception rather than the rule.

The Benin discoveries shatter that framework.

They show that African states were not only capable of large-scale engineering, but were doing it independently, efficiently, and sustainably.

One archaeologist involved in the research described the moment the full extent became clear as “deeply uncomfortable.

” Not because the evidence was unclear, but because it contradicted so much of what had been taught.

“We weren’t missing the data,” he said.

“We were missing the willingness to believe it.

”

The earthworks also tell a darker story.

Historical records confirm that large portions of Benin City were destroyed during the British punitive expedition of 1897.

Walls were dismantled.

Artifacts were looted.

Landscapes were altered.

What archaeologists are now finding beneath the soil are fragments that survived deliberate erasure.

The destruction was so thorough that later scholars assumed the original accounts must have been exaggerated.

They were not.

What lay beneath Benin City was hidden not by time alone, but by violence and neglect.

Modern construction unknowingly covered ancient trenches.

Forests reclaimed embankments.

Generations grew up unaware that beneath their feet lay evidence of one of the most ambitious urban projects in human history.

As excavation continues, researchers are beginning to understand how the earthworks functioned not just as defenses, but as symbols.

The walls marked boundaries of authority.

The moats controlled movement.

Roads aligned with political and spiritual centers.

The city was designed to be read, navigated, and understood by those who lived within it.

This challenges another long-held assumption: that African cities were chaotic or unplanned.

Benin City was the opposite.

It was ordered, intentional, and deeply interconnected with its surrounding region.

The earthworks were not the edge of civilization—they were its framework.

The discovery is now reshaping academic curricula, museum narratives, and global conversations about what constitutes “advanced” society.

Scholars are calling for a reevaluation of how archaeological attention has been distributed and why certain regions were dismissed too quickly.

The question is no longer whether Benin was exceptional, but how many other African landscapes still conceal histories written into the earth rather than stone.

Perhaps the most profound impact is cultural.

For descendants of the Edo people, the findings are not a surprise so much as a confirmation.

Oral histories spoke of walls without end, of cities protected by human effort and divine mandate.

Those stories were long treated as folklore.

Archaeology has now validated them, not symbolically, but physically.

What archaeologists found beneath Benin City does not merely add a chapter to history.

It overturns the table.

It proves that complexity, innovation, and large-scale organization flourished in West Africa on a level that demands global recognition.

It exposes how much was lost—not because it never existed, but because it was never allowed to remain visible.

History did not change because something new was built beneath Benin City.

It changed because what was always there has finally been seen.

News

🌴 Population Shift Shakes the Golden State: What California’s Migration Numbers Are Signaling

📉 Hundreds of Thousands Depart: The Debate Growing Around California’s Changing Population California has long stood as a symbol…

🌴 Where Champions Recharge: The Design and Details Behind a Golf Icon’s Private Retreat

🏌️ Inside the Gates: A Look at the Precision, Privacy, and Power of Tiger Woods’ Jupiter Island Estate On…

⚠️ A 155-Year Chapter Shifts: Business Decision Ignites Questions About Minnesota’s Future

🌎 Jobs, Growth, and Identity: Why One Company’s Move Is Stirring Big Reactions For more than a century and…

🐍 Nature Fights Back: Florida’s Unusual Predator Plan Sparks New Wildlife Debate

🌿 From Mocked to Monitored: The Controversial Strategy Targeting Invasive Snakes Florida’s battle with invasive wildlife has produced many…

🔍 Ancient Symbols, Modern Tech: What 3D Imaging Is Uncovering Beneath History’s Oldest Monument

⏳ Before the Pyramids: Advanced Scans Expose Hidden Features of a Prehistoric Mystery High on a windswept hill in…

🕳️ Secrets Beneath the Rock: Camera Probe Inside Alcatraz Tunnel Sparks Chilling Questions

🎥 Into the Forbidden Passage: What a Camera Found Under Alcatraz Is Fueling Intense Debate Alcatraz Island has…

End of content

No more pages to load