💔 The Girl With the Bruised Lip: The Haunting Story Behind Auschwitz’s Most Heartbreaking Photograph

When Czesława Kwoka arrived at Auschwitz in December 1942, she was just a frightened Polish schoolgirl from Wólka Złojecka, a small village near Zamość.

She didn’t understand the German commands being shouted at her.

She didn’t know where she was being taken.

She had lost her mother, Katarzyna, only days earlier — another casualty of the Nazi regime’s brutal “Generalplan Ost,” which sought to erase entire Polish communities.

The Nazis’ bureaucratic machine of extermination documented everything.

Every prisoner received a number, a category, and a photograph.

And so, when Czesława entered Auschwitz-Birkenau, she became Prisoner 26947.

Before she was executed, her face was photographed three times — from the front, from the side, and at an angle.

The task fell to another prisoner: Wilhelm Brasse, an Austrian-Polish photographer forced by the SS to document inmates as part of the camp’s “Erkennungsdienst,” or identification unit.

Brasse would later recall that day with a voice that broke under the weight of memory.

He remembered how terrified she looked.

How she couldn’t stop crying.

How an SS woman, impatient with her sobbing, struck her across the mouth, leaving the dark mark visible on her lip in the photo.

“She was so young and so frightened,” Brasse said years later in an interview for the documentary The Portraitist.

“I remember the black mark.

I remember she cried, but she did not understand what was happening.

A few weeks later, on February 18, 1943, Czesława was murdered with an injection of phenol directly into her heart — one of the Nazis’ preferred methods for killing children.

She was just 14 years old.

In that one moment, her life — her laughter, her language, her future — was erased.

But her image survived.

The negatives of Brasse’s photographs were hidden in secret by members of the Auschwitz resistance before the camp was liberated.

Decades later, they became part of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum archives in Oświęcim, Poland.

Among the thousands of mugshots, one face seemed to stop visitors in their tracks — that of the little girl with the bruised lip, eyes filled with terror and pleading.

Over the years, the photograph has been reprinted countless times in history books, exhibitions, and memorials.

It has become not just a record of one girl’s suffering, but a haunting reminder of the 250,000 children and teenagers who were murdered in Auschwitz — each of them a story that could have been lost forever.

For decades, the image existed only in stark black and white — as cold and clinical as the system that produced it.

Then, in 2018, a Brazilian artist named Marina Amaral (sometimes misspelled “Anna Amaral”) decided to give it color — not to beautify it, but to humanize it.

She had been researching historical photographs to bring life to forgotten faces, and when she found Czesława’s image in the archives, she was struck to her core.

“I couldn’t stop looking at her eyes,” Amaral said.

“I wanted to remind people that she was a real child.

That she once had color in her cheeks.

That she was alive.

Using painstaking digital techniques, Amaral colorized the photograph — the gray prison fabric became rough brown cloth, the background a pale institutional blue.

But what drew the most attention was Czesława’s skin — still pale, still bruised, but suddenly human.

The bruise on her lip became real again, not just a dark blotch but a wound inflicted by cruelty.

“Color doesn’t change the history,” Amaral explained.

“It just helps us feel it.

When the colorized image went viral online, it reawakened global conversation about how we remember the Holocaust.

People who had never read about Auschwitz shared the picture, some thinking it was newly taken, others writing messages of sorrow and disbelief.

Teachers used it to help students understand that behind every statistic was a face, a name, and a heartbeat.

Historians praised Amaral’s work for its emotional power.

Survivors called it “a resurrection of memory.

” And in the museum at Oświęcim, visitors began leaving small notes and flowers beneath Czesława’s portrait — as if apologizing to her, decades too late, for a world that failed to protect her.

Wilhelm Brasse, the man who took her photograph, lived until 2012.

He never escaped the faces he was forced to capture.

“When I close my eyes,” he once said, “I still see them — all those eyes looking back at me.

” For him, photographing prisoners was both an act of survival and an unbearable curse.

He refused to destroy the negatives, even under Nazi orders, because he felt someone had to remember.

“One day,” he said, “the world will need proof.

And so, proof remains.

Today, in classrooms and museums across the world, people still meet Czesława Kwoka’s gaze.

Some see fear.

Others see defiance.

But everyone feels the same weight — a child robbed of everything, yet somehow immortalized in her final moment.

Her story is not one of numbers or statistics, but of humanity — the fragile, flickering kind that even a genocide couldn’t erase.

In the reflection of her eyes, we see the echo of a question that has haunted history: How could anyone look at her and still choose cruelty?

Czesława’s face, once the anonymous record of a victim, has become something more powerful — a symbol of remembrance, a reminder that empathy is an act of resistance.

The photograph taken in fear now stands as defiance against forgetting.

When visitors stand before her image in the Auschwitz Memorial today, they often fall silent.

Some whisper prayers.

Some cry.

Some simply stare.

Because even eighty years later, her eyes still speak.

They tell us not to look away.

They tell us to remember.

News

🤯 “We Expected Better” — The Emotional Backlash Against Ayesha Curry’s Controversial Remarks That Shook Social Media!

😱 The Internet Turns on Ayesha Curry — Why Her Latest Comments Have Sparked a Storm Among Women Everywhere! …

😱 He Stole a Car… Then Discovered What Was in the Backseat — The Twist No One Saw Coming in Oregon!

A Crime, a Conscience, and a Baby: The Wild True Story That Left Police (and the Internet) Speechless! The…

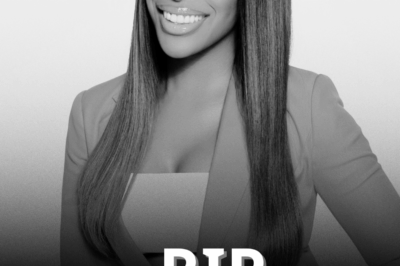

💔 The Internet Killed Her Before the Truth Came Out — Inside the Viral Death Hoax That Shook Jackie Aina’s Fans!

“Four Words Before the Crash” — How a Fake Headline About Jackie Aina’s Death Fooled Millions and Exposed the Dark…

💥 The Real Reason Sam Lovegrove Disappeared from Shed and Buried — His Confession Will Shock You!

When the Cameras Stopped Rolling: Sam Lovegrove Reveals the Dark Truth Behind His Exit from Shed and Buried! When…

💔 Blake Shelton Finally Reveals the Truth About Kelly Clarkson — And It Changes Everything!

Tears, Truth, and Tension: Blake Shelton’s Emotional Admission About Kelly Clarkson That No One Saw Coming! When Blake Shelton…

💔 Seven Years Later, Jerry Lewis’ Son Finally Speaks — What He Reveals About His Father Will Leave You Speechless!

“I Swore I’d Never Talk About It” — The Hidden Truth Jerry Lewis’ Son Just Exposed After Decades of Silence!…

End of content

No more pages to load