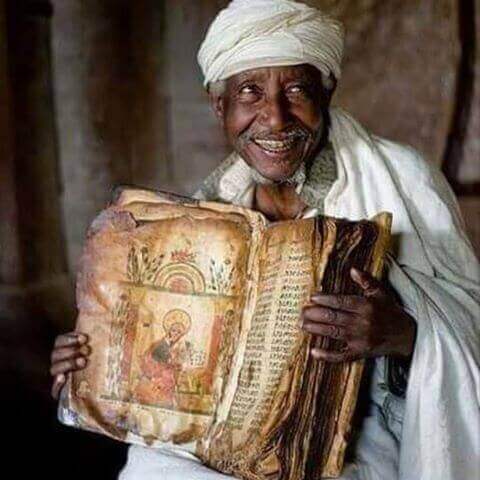

“Hidden No More: The Resurrection Passage Ethiopia Protected for Generations Is Finally Exposed”

For centuries, it was whispered about but never seen.

A resurrection passage guarded in silence, preserved in ancient ink, locked away behind stone walls and strict vows.

Now, after generations of refusal, Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church monks have finally allowed a translated version of this closely protected resurrection text to be released.

And according to scholars who have read it, the implications are nothing short of seismic.

The passage comes from an ancient manuscript written in Ge’ez, a classical language no longer spoken in daily life but still used in sacred Ethiopian texts.

Unlike the canonical resurrection accounts familiar to most Christians, this version offers startling details that have never appeared in mainstream scripture.

It describes events before, during, and after the resurrection with a level of intimacy and symbolism that has left historians unsettled and theologians divided.

According to the translated text, the resurrection was not a single moment, but a process.

The passage speaks of a period of transformation rather than instant triumph, describing a liminal state in which time itself appeared to pause.

The tomb is not portrayed merely as empty, but as altered — “opened not by stone, but by command,” as one line reportedly reads.

This language suggests an event that was not only physical, but cosmic, challenging long-held interpretations taught for centuries.

Perhaps most controversial is the role assigned to witnesses.

The manuscript claims that the resurrection was observed not only by followers, but by unseen forces described as “watchers of the threshold,” entities neither human nor angelic in the traditional sense.

This alone has ignited fierce debate.

Some scholars interpret the wording as poetic metaphor rooted in ancient Near Eastern cosmology.

Others argue it reflects a theological worldview deliberately excluded when early church authorities standardized scripture.

Equally shocking is how the resurrected figure is described.

Rather than immediately appearing to crowds, the text suggests a period of withdrawal — a time of instruction given only to a select few, emphasizing inner transformation over public proof.

This portrayal challenges the modern emphasis on spectacle and certainty, replacing it with mystery and gradual revelation.

For believers, it reframes resurrection not as an endpoint, but as the beginning of a deeper, more demanding journey.

Why was this passage hidden for so long? Ethiopian monks have historically maintained that some texts are not meant for every era.

Oral tradition within monasteries teaches that certain writings are released only when humanity is spiritually prepared to wrestle with them.

Until now, these resurrection passages were shared only among senior monks during advanced theological instruction, never translated, never published, and never discussed outside monastery walls.

The decision to release the translation did not come easily.

Sources close to the monasteries say internal debate lasted years.

Concerns ranged from misinterpretation to politicization, especially in an age of viral misinformation.

Ultimately, the monks concluded that withholding the text might cause more harm than revealing it, particularly as fragments and rumors had already begun circulating online without context or accuracy.

Academic reaction has been intense.

Biblical historians point out that Ethiopia’s Christian tradition developed independently from Rome and Byzantium for centuries, preserving texts lost or excluded elsewhere.

The Ethiopian biblical canon already contains books unfamiliar to Western Christianity, and this resurrection passage further reinforces the idea that early Christian history was far more diverse than commonly acknowledged.

Theologians are split.

Some argue the passage deepens faith by restoring mystery and humility to the resurrection narrative.

Others warn it could destabilize doctrine, especially for communities built on rigid interpretations.

Yet even critics admit the text does not contradict the resurrection — it expands it, shifting focus from proof to transformation, from victory to responsibility.

For ordinary believers, the emotional impact may be the greatest.

The resurrection described here is not clean, simple, or triumphant in a cinematic sense.

It is unsettling, demanding, and deeply personal.

It asks readers not merely to believe, but to change.

That, some monks say, is precisely why it was kept hidden for so long.

As translations continue to be reviewed and debated, one truth is already clear: this is not just another ancient manuscript.

It forces a reexamination of what resurrection means, not only historically, but spiritually.

It suggests that something essential was never lost — only delayed, waiting for a moment when the world was finally ready to listen.

Whether embraced or rejected, the released passage has already achieved what centuries of silence could not.

It has reopened the conversation about faith, authority, and the unseen dimensions of belief.

And once such questions are asked, they cannot be easily buried again.

News

🌴 Population Shift Shakes the Golden State: What California’s Migration Numbers Are Signaling

📉 Hundreds of Thousands Depart: The Debate Growing Around California’s Changing Population California has long stood as a symbol…

🌴 Where Champions Recharge: The Design and Details Behind a Golf Icon’s Private Retreat

🏌️ Inside the Gates: A Look at the Precision, Privacy, and Power of Tiger Woods’ Jupiter Island Estate On…

⚠️ A 155-Year Chapter Shifts: Business Decision Ignites Questions About Minnesota’s Future

🌎 Jobs, Growth, and Identity: Why One Company’s Move Is Stirring Big Reactions For more than a century and…

🐍 Nature Fights Back: Florida’s Unusual Predator Plan Sparks New Wildlife Debate

🌿 From Mocked to Monitored: The Controversial Strategy Targeting Invasive Snakes Florida’s battle with invasive wildlife has produced many…

🔍 Ancient Symbols, Modern Tech: What 3D Imaging Is Uncovering Beneath History’s Oldest Monument

⏳ Before the Pyramids: Advanced Scans Expose Hidden Features of a Prehistoric Mystery High on a windswept hill in…

🕳️ Secrets Beneath the Rock: Camera Probe Inside Alcatraz Tunnel Sparks Chilling Questions

🎥 Into the Forbidden Passage: What a Camera Found Under Alcatraz Is Fueling Intense Debate Alcatraz Island has…

End of content

No more pages to load