SCIENTISTS X-RAYED A 2,300-YEAR-OLD MUMMY — AND FROZE IN SILENCE

The room was silent except for the low mechanical hum of the scanner.

Monitors glowed softly as scientists gathered around, expecting nothing more than routine data from a body that had been dead for over 2,300 years.

Ancient mummies had been scanned before.

Bones, wrappings, amulets—nothing unfamiliar.

But as the first images appeared on the screen, the atmosphere shifted.

No one spoke.

Several researchers instinctively stepped closer.

Others simply stared.

What they were seeing was not supposed to be there.

The mummy, dating to the late Ptolemaic period of ancient Egypt, had been remarkably well preserved.

Its linen wrappings were intact, its sarcophagus untouched for centuries.

When it was transported from storage to a modern medical facility near Cairo, the goal was simple: perform a non-invasive X-ray and CT scan to learn more about age, health, and burial practices.

No one expected the scan to rewrite everything they thought they knew about ancient mummification.

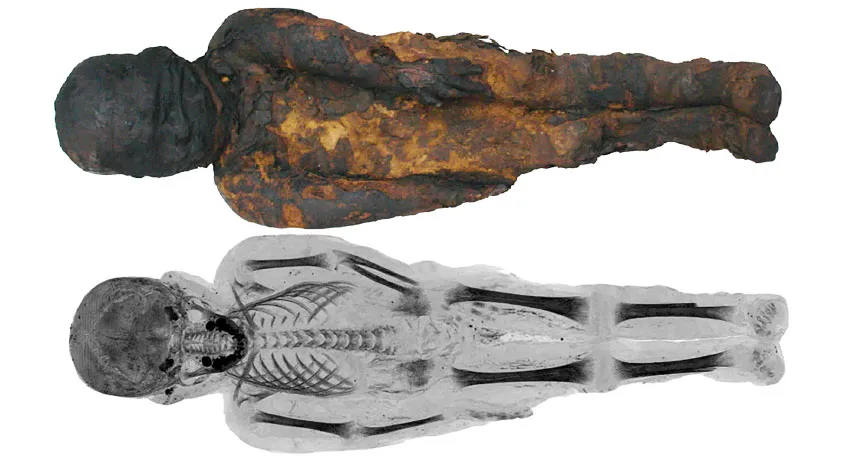

As the X-ray penetrated layers of linen and resin, the skeletal structure came into focus.

The bones told a familiar story at first: an adult individual, likely male, well nourished, with no obvious signs of hard labor.

But then the scan reached the chest cavity—and the silence began.

The heart was still there.

In most Egyptian mummies, the heart was removed during embalming or replaced with a symbolic amulet.

Ancient texts describe the heart as the seat of intelligence and morality, weighed against the feather of Ma’at in the afterlife.

Embalmers treated it with ritual care.

Yet in this mummy, the heart appeared physically intact, positioned exactly where it would have been in life.

That alone was extraordinary.

But it was only the beginning.

Further scans revealed dozens of amulets hidden beneath the wrappings, far more than typically found.

Scarabs, eye symbols, and protective charms were placed with surgical precision.

Some were embedded between layers of linen.

Others rested directly against organs.

One amulet, shaped unlike any cataloged example, was positioned over the heart itself.

Its design did not match known funerary objects from the period.

Researchers exchanged uneasy glances.

This was not standard practice.

This was intentional deviation.

As the team adjusted the imaging depth, something even more unsettling appeared.

The brain had not been removed.

For centuries, Egyptologists believed brain removal through the nasal cavity was nearly universal during mummification.

The brain was considered insignificant compared to the heart.

But the scan showed remnants of neural tissue preserved within the skull.

Not displaced.

Not damaged.

Deliberately left in place.

This contradicted everything taught in textbooks.

The room grew colder, or at least it felt that way.

One senior researcher reportedly whispered, “This changes things.

” And it did.

The mummy appeared to have undergone a unique embalming process, one reserved for someone of extraordinary status—or extraordinary purpose.

Chemical analysis of the resins detected rare compounds imported from distant regions, substances too expensive for ordinary elites.

The linen quality surpassed that used for many known nobles.

Whoever this person was, they were important.

But no inscriptions identified their name.

The mystery deepened when forensic analysis suggested the individual died young, possibly in their early 30s, with no signs of disease or trauma.

Yet ritual markers indicated extreme spiritual preparation.

It was as if the embalmers believed this individual required additional protection in the afterlife—or posed a risk without it.

Some scholars cautiously suggested the mummy may have belonged to a high-ranking priest involved in forbidden rituals.

Others speculated about connections to secret cults active during the unstable final centuries of ancient Egypt.

At that time, Greek and Egyptian religious traditions intertwined, sometimes clashing, sometimes merging into practices still poorly understood.

What froze the scientists in silence was not fear, but realization.

This mummy was not passive history.

It was evidence of knowledge lost, practices deliberately hidden, and beliefs powerful enough to defy tradition.

Modern technology had peeled back layers of linen, but it had also peeled back assumptions.

This was not just a body.

It was a message across millennia.

The scans were paused multiple times as the team debated what they were seeing.

No one wanted to jump to conclusions.

Data was double-checked.

Images were reprocessed.

The results did not change.

The heart, the brain, the amulets, the unusual preservation—everything pointed to a funerary ritual never fully documented.

When news of the findings reached Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities, access to the mummy was immediately restricted.

Further analysis was approved, but under strict supervision.

The public was told only that “unexpected features” had been discovered.

Behind closed doors, experts understood the implications.

If this mummy represented a broader, unknown tradition, then entire chapters of ancient Egyptian belief systems may be missing from history.

The most haunting detail emerged last.

A faint object appeared near the throat, almost invisible without enhanced contrast.

It resembled a thin metallic plate, placed deliberately beneath the wrappings.

In ancient texts, the throat was associated with speech, names, and identity in the afterlife.

The plate bore markings too worn to read—yet clearly intentional.

The scientists did not speak as the scan ended.

They removed their gloves slowly.

One by one, they left the room.

Not out of fear—but respect.

After 2,300 years, the mummy had finally spoken.

And no one was ready for what it said.

News

🌴 Population Shift Shakes the Golden State: What California’s Migration Numbers Are Signaling

📉 Hundreds of Thousands Depart: The Debate Growing Around California’s Changing Population California has long stood as a symbol…

🌴 Where Champions Recharge: The Design and Details Behind a Golf Icon’s Private Retreat

🏌️ Inside the Gates: A Look at the Precision, Privacy, and Power of Tiger Woods’ Jupiter Island Estate On…

⚠️ A 155-Year Chapter Shifts: Business Decision Ignites Questions About Minnesota’s Future

🌎 Jobs, Growth, and Identity: Why One Company’s Move Is Stirring Big Reactions For more than a century and…

🐍 Nature Fights Back: Florida’s Unusual Predator Plan Sparks New Wildlife Debate

🌿 From Mocked to Monitored: The Controversial Strategy Targeting Invasive Snakes Florida’s battle with invasive wildlife has produced many…

🔍 Ancient Symbols, Modern Tech: What 3D Imaging Is Uncovering Beneath History’s Oldest Monument

⏳ Before the Pyramids: Advanced Scans Expose Hidden Features of a Prehistoric Mystery High on a windswept hill in…

🕳️ Secrets Beneath the Rock: Camera Probe Inside Alcatraz Tunnel Sparks Chilling Questions

🎥 Into the Forbidden Passage: What a Camera Found Under Alcatraz Is Fueling Intense Debate Alcatraz Island has…

End of content

No more pages to load