Lee Harvey Oswald: The Making of a Man History Would Never Forgive

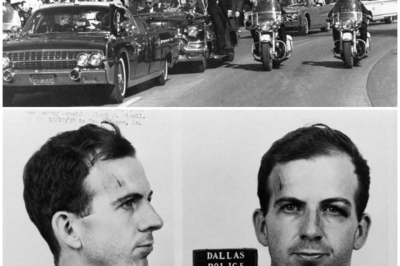

On November 22, 1963, a single rifle shot cut through the cheers of a Dallas crowd and tore open the illusion of American innocence. President John F. Kennedy, young, charismatic, and emblematic of a hopeful generation, collapsed in his motorcade. Within minutes, the world was changed forever. At the center of that moment stood a 24-year-old former Marine named Lee Harvey Oswald, a man whose life had been a long, restless march toward notoriety.

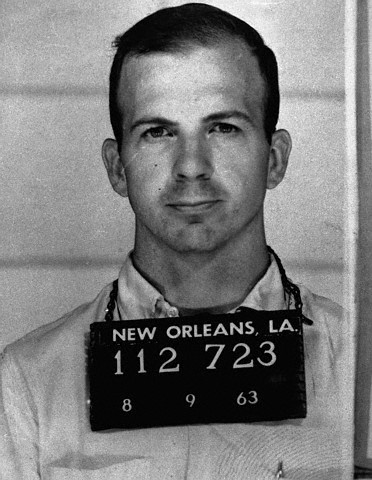

Oswald’s story did not begin with politics or ideology, but with abandonment. Born in 1939 to a widowed mother in New Orleans, he entered a world already defined by loss. His father died before he was born, and his childhood became a grim cycle of orphanages, temporary apartments, and broken promises. Stability was a foreign concept. By his early teens, Oswald had moved more times than most people would in a lifetime, drifting through relatives’ homes and state institutions, learning early that attachment only led to disappointment.

Lonely and resentful, Oswald became withdrawn and volatile. Teachers described him as surly and isolated. Authorities noted his violent tendencies, but found no clear mental illness—only neglect and emotional deprivation. He was a boy with no anchor, no sense of belonging, and an intense hunger for meaning. That hunger soon found an outlet in ideology.

In the early 1950s, amid the execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg for espionage, Oswald encountered socialist literature for the first time. What began as curiosity hardened into obsession. Marxism offered him something he had never known: a worldview that framed his alienation as virtue and promised purpose through opposition. It told him he mattered, even if the world had treated him as disposable.

Seeking escape, Oswald joined the United States Marine Corps in 1956. The Marines gave him structure, weapons training, and a fleeting sense of importance. He became a certified sharpshooter and learned Russian, all while openly praising Marxist ideas during the height of the Cold War. Predictably, his time in uniform ended badly. Court-martialed, imprisoned in the brig, and discharged under undesirable conditions, Oswald left the Marines more bitter and radicalized than before.

In 1959, he made a move that stunned even those who knew him well: he defected to the Soviet Union. But the romantic fantasy of defecting to a communist paradise quickly collapsed. Soviet authorities viewed him with suspicion and indifference. Rejected and humiliated, Oswald attempted suicide before forcing the Kremlin’s hand by threatening to reveal U.S. military secrets. Eventually allowed to stay, he was exiled to Minsk, a gray, surveilled city where disillusionment replaced idealism.

Though initially treated as a curiosity, Oswald soon found Soviet life suffocating. His apartment was bugged, his movements monitored, his work monotonous. The promised workers’ utopia felt hollow. In Minsk, he married Marina Prusakova and became a father, but domestic life did little to quiet his frustrations. Gradually, Oswald turned his gaze back toward America—not with reconciliation, but with resentment.

When his attempt to clear his military discharge was rebuffed by U.S. officials, particularly John Connally, Oswald developed a personal vendetta. By 1962, he had returned to the United States with his family, settling in Texas. Here, his fixation shifted again, this time toward Cuba and Fidel Castro. Oswald publicly defended Castro, distributed pro-Cuban leaflets, and sought connections on both sides of the political spectrum, as if auditioning for a role in history.

Violence soon followed ideology. In April 1963, Oswald attempted to assassinate former General Edwin Walker, firing a bullet through his window and narrowly missing. Convinced he had killed Walker, Oswald fled the scene, only to discover later that his target had survived. It was a rehearsal for something far larger.

Later that year, Oswald traveled to Mexico City, desperately attempting to defect to Cuba via the Soviet Union. He was rejected by both. Whether he met intelligence operatives or simply spiraled further into desperation remains debated, but when he returned to Dallas, his path seemed set. He took a job at the Texas School Book Depository. Fate, or coincidence, placed him directly along the route of the presidential motorcade.

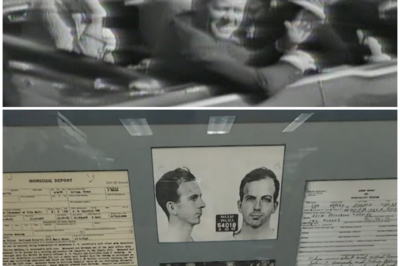

On the morning of November 22, Oswald brought his rifle to work. Just after 12:30 p.m., he fired the shots that killed President Kennedy and wounded Governor Connally. In seconds, the obscure drifter became the most infamous man in America. He fled, killed a police officer, and was arrested later that day. The world barely had time to process his guilt or innocence before history intervened again.

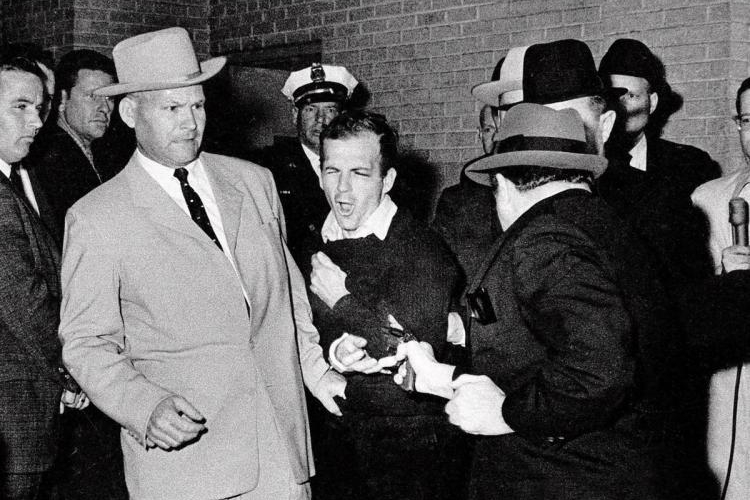

Two days later, while in police custody, Oswald was shot dead by nightclub owner Jack Ruby, live on television. His murder ensured that the full truth of his motives would remain forever out of reach. Conspiracy theories exploded, feeding on the silence left by a man who could no longer speak.

Oswald was buried on the same day as Kennedy. One man mourned as a martyr, the other remembered as a monster. Yet beyond the headlines and theories lies a colder truth: Lee Harvey Oswald was not a mastermind or a puppet kingpin. He was a profoundly lost individual, shaped by neglect, obsession, and an overwhelming desire to be seen. In the end, he did achieve significance—but at the cost of becoming a symbol of tragedy rather than purpose.

History did not remember him as he wished. It remembered him as the man who pulled the trigger, and then vanished into blood and silence.

News

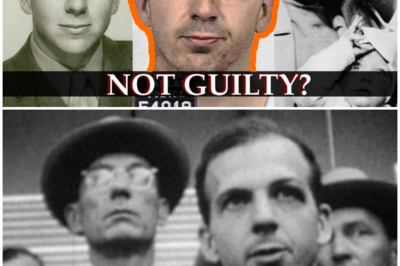

LEE HARVEY OSWALD: Innocent or Guilty? 11 Incredible Facts

The assassination of President John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963, remains one of the most scrutinized and emotionally charged…

Rob Reiner Solves JFK A.s.s.a.s.s.i.n.a.t.i.o.n and Names 4 Suspects

On a crisp autumn day in Dallas in 1963, a single burst of violence forever altered the course of American…

JFK Unsolved: The Real Conspiracies

The Last Second in Dallas: How New Evidence Rewrites the JFK Assassination The assassination of President John F. Kennedy on…

JFK stories from WFAA through the years

Few events in modern American history have been analyzed as obsessively as the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Every…

What They Did with JFKs Coffin is Highly Suspicious

For decades, the assassination of President John F. Kennedy has been examined from nearly every imaginable angle. Ballistics, eyewitnesses, medical…

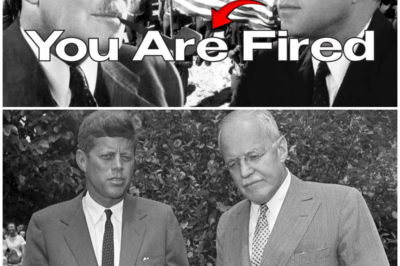

What Allen Dulles Said When Kennedy Fired Him

On September 27, 1961, inside the Oval Office of the White House, a moment unfolded that would quietly reshape the…

End of content

No more pages to load