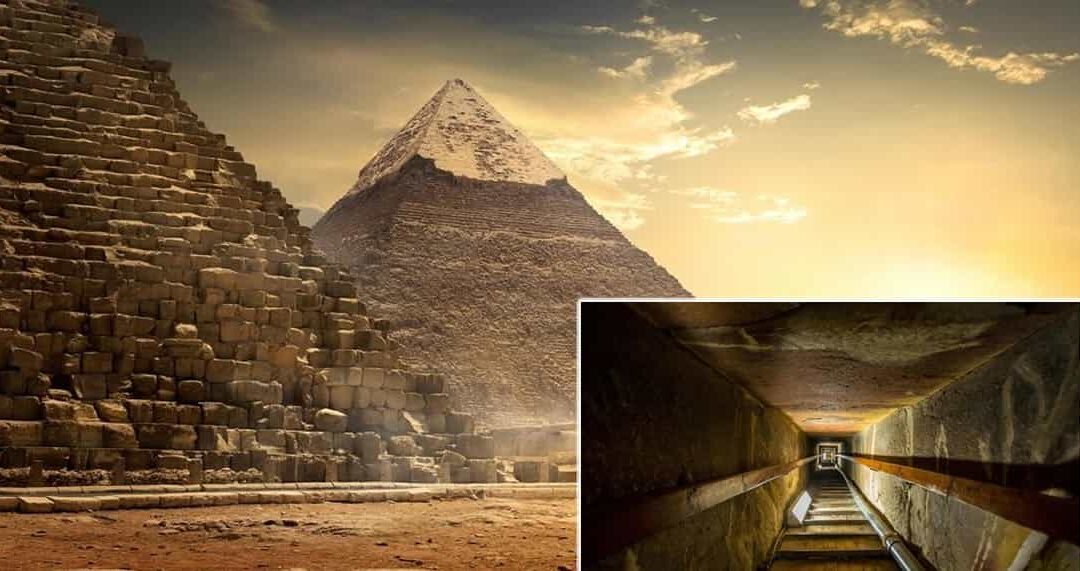

The Great Pyramid of Giza, the last surviving wonder of the ancient world, continues to captivate historians, scientists, and the public alike.

For generations, it has been attributed to Pharaoh Khufu of Egypt’s Fourth Dynasty, yet ongoing discoveries suggest the pyramid’s story may be more complex than previously imagined.

Long shrouded in mystery, the Great Pyramid was originally encased in polished white Tura limestone, reflecting sunlight so brilliantly that it appeared seamless, a perfect wedge of stone with no visible entrance.

Over millennia, the outer casing eroded, leaving the rough core observed today.

The smooth, reflective surface, however, was key to its original design and the concealment of its hidden entrance.

The main entrance to the pyramid is situated on the north face, approximately 56 feet above the ground and slightly east of the center.

Originally, the entrance blended flawlessly with the casing stones, effectively concealing it.

Historical accounts suggest the existence of a movable block that could provide entry, yet by the medieval period, the exact location of the entrance had been lost.

In the ninth century, Caliph Al-Ma’mun of the Abbasid dynasty attempted to breach the pyramid in search of treasure.

His team tunneled into the north face, reportedly hearing a crack as a hidden stone shifted, revealing the original passage.

Though some details of this story remain debated, the tunnel his men created is still accessible to visitors today.

Inside, the descending passage begins as a narrow corridor just under four feet high and slightly over three feet wide, forcing those who enter to stoop.

The passage descends into bedrock, culminating in an unfinished subterranean chamber, sometimes referred to as the pit.

This chamber lies approximately 90 feet below the pyramid’s base, measuring 46 feet east to west, 27 feet north to south, and up to 13 feet in height.

Its rough walls and uneven floors suggest construction was halted, possibly leaving a symbolic representation of the underworld or an abandoned burial space.

No pharaoh’s remains have ever been found in this chamber or elsewhere in the pyramid.

Within this lower system, other features include a deep man-made hole known as Pering’s shaft, which explorers in the 19th century dug in hopes of finding a hidden lake described by the historian Herodotus.

Although the shaft eventually reached the water table, no lake was discovered.

Another vertical chute, the well shaft, links the subterranean areas to higher passages and may have served as a practical escape route or construction shortcut.

These lower passages were deliberately concealed and difficult to access, reflecting the importance of secrecy and perhaps symbolic representation in the pyramid’s design.

Above the descending passage, the corridor turns upward into the ascending passage, hidden behind massive granite blocks.

This slope leads into the Grand Gallery, a remarkable stone ramp nearly 154 feet long and 29 feet high, with side ledges featuring slots likely used for the controlled placement of massive blocks.

The walls step inward in layers, while the ceiling is angled to distribute weight effectively, preventing collapse.

Midway along the gallery, a side corridor leads to the Queen’s Chamber, a small, finely finished limestone room with a gabled roof and a niche on the east wall of unknown purpose.

At the top of the Grand Gallery lies the King’s Chamber, constructed entirely of pink granite from Aswan.

The chamber is approximately 34.

5 feet long, 17 feet wide, and 19 feet high, housing a granite sarcophagus that could only have been placed before the chamber’s roof was completed.

Above this chamber are five relieving chambers designed to distribute the immense weight of the pyramid, a testament to the ancient builders’ engineering sophistication.

Each chamber forms horizontal voids to divert pressure from the King’s Chamber, protecting it from structural failure.

Modern technology has dramatically expanded knowledge of the pyramid’s hidden spaces.

Particle detectors, ground-penetrating radar, and ultrasound imaging allow researchers to observe internal structures without disturbing the stone.

Muon radiography, in particular, has revealed a previously unknown cavity, the “Big Void,” above the Grand Gallery, measuring nearly 98 feet in length.

Another corridor-shaped space, found behind the chevron-patterned blocks above the original north entrance, measures roughly 30 feet long.

These discoveries are confirmed using multiple techniques, including endoscopic cameras inserted through narrow gaps, ensuring precision and preservation.

The Queen’s Chamber contains two narrow shafts initially believed to serve as ventilation.

Both terminate in blocked stone doors.

Robotic probes have revealed the intricate design of these blockages, with copper fittings suggesting deliberate intent rather than mere obstruction.

Images captured by flexible snake-like robots revealed red markings on the floor, likely related to measurements or alignment, adding further evidence of the builders’ precise planning.

These shafts, muon-detected cavities, and hidden corridors illustrate that the Great Pyramid remains largely unexplored, and its purpose continues to invite speculation.

The surrounding landscape of Giza provides further context for the construction and function of the pyramids.

In 1954, two boat-shaped pits were discovered near Khufu’s pyramid.

The first contained over 1,000 timbers that were meticulously reconstructed into a full-sized cedar ship, approximately 142 feet long, intended for use in the pharaoh’s funerary rites or to symbolize the sun god’s journey across the sky.

The second boat pit, excavated and restored decades later with international support, reinforced the importance of these ritual vessels in Egyptian beliefs surrounding death and the afterlife.

The lives of the workers who built the pyramids have also been illuminated.

Archaeologists uncovered tombs near the Giza plateau indicating organized crews rather than enslaved laborers.

Workers were provided with food, medical care, and housing in a settlement called Heit el-Ghurab, covering over 17 acres.

The settlement contained barracks, bakeries, and administrative buildings, supporting a labor force whose diet included substantial amounts of meat, bread, and beer.

Evidence of healed injuries and surgical procedures demonstrates that workers were valued and cared for, reflecting a well-organized, state-supported labor system rather than forced labor.

Further discoveries include the mortuary and valley temples associated with Khufu, along with tombs of family members such as Queen Hetepheres I.

Excavations revealed luxury burial goods, offering insight into the wealth and ritual practices of Egypt’s Fourth Dynasty.

Mortuary temples were centers for rituals designed to sustain the king’s spirit, emphasizing the interconnection between religious practice and monumental construction.

Smaller pyramids, such as the tomb of Queen Khentkaus I, were accompanied by cultic structures and settlements, underscoring the broader cultural landscape surrounding the pyramids.

Taken together, these findings transform the perception of Giza from a site of static monuments to a living, complex civilization.

It was a hub of engineering, religion, labor, and administration, integrated with river transport for materials, food, and timber.

The pyramids were part of a sophisticated system of construction, ceremonial activity, and community life.

Far from the image of isolated stone structures built by slaves, Giza was a carefully organized landscape, where construction, ritual, and daily life were interwoven in a remarkable expression of ancient Egyptian civilization.

In conclusion, the Great Pyramid of Giza remains a testament to human ingenuity and ambition.

Its hidden chambers, meticulously engineered structures, and the carefully documented lives of those who built it demonstrate a level of sophistication that continues to challenge modern understanding.

Advances in technology are now revealing the pyramid’s secrets without disturbing its structure, offering unprecedented opportunities to study its construction, design, and symbolic intent.

Beyond the stones themselves, the surrounding temples, settlements, and artifacts reflect a vibrant society capable of monumental achievement.

The Great Pyramid is not merely a tomb but a center of culture, belief, and labor that continues to inspire awe and curiosity.

Its mysteries are far from fully revealed, suggesting that even today, thousands of years later, the story of Khufu’s pyramid is still unfolding.

News

76 Terrifying Secrets The Vatican Is Hiding From Us – Unsolved Mysteries For centuries, the Vatican has been a fortress of hidden knowledge, forbidden artifacts, and unexplained phenomena that most of the world can only speculate about. From secret manuscripts and lost relics to mysterious chambers and unexplained events, these 76 secrets reveal a side of the Church few have ever seen.

Could some of these mysteries rewrite history, expose long-hidden truths, or reveal dangerous knowledge the world wasn’t ready for? What lies beneath the Vatican continues to shock and intrigue researchers and conspiracy theorists alike.

Unveiling the Secrets of the Vatican: A Journey into the Unknown The Vatican, a city-state steeped in history and religious…

MOST Terrifying Secrets The Vatican Is Hiding From Us – Unsolved Mysteries

The Vatican has long been regarded as a repository of secrets, a place where history, religion, and mystery intertwine in…

Pope Leo XIV Has Just Changed Mary Forever: Catholics Are Fighting!

A seismic shift has struck the Catholic Church. For centuries, the Virgin Mary has occupied a place of unparalleled reverence…

The Meeting ENDED IN CHAOS Pope Leo XIV Calls for FULL COMMUNION with ORTHODOX SHOCKING REVELATION

The Day the Vatican Hall Shattered: Pope Leo I 14th’s Bold Call for Christian Unity On the morning of May…

What They Just Found In The Basement Of The Vatican SHOCKS Everyone Deep beneath the Vatican, researchers have uncovered a hidden chamber that has been sealed for centuries, revealing mysterious artifacts, ancient manuscripts, and unexplained relics. The discovery raises urgent questions: What secrets were kept hidden? Who hid them? And why now? Historians and investigators are stunned, as this find could rewrite our understanding of the Vatican, hidden knowledge, and centuries-old mysteries.

The shocking revelation is sending waves through the world—and the truth is stranger than anyone imagined.

Deep within the corridors of the Vatican, a combination of history, mystery, and legend intertwines, creating an atmosphere that has…

Mel Gibson: “They’re Lying To You About The Shroud of Turin!”

Mel Gibson, one of Hollywood’s most recognizable figures, has long been known for his contributions to both acting and filmmaking….

End of content

No more pages to load