It arrived with no return address, only a handwritten note: “This belonged to my family.

I believe others should see it and understand it.

Please share her story.”

On a cool October morning in 2024, Dr.

Amelia Richardson stood in her office at the American Legacy Museum in Richmond, Virginia, where she served as senior curator of African American history after the Civil War.

She carefully unwrapped tissue paper from a wooden frame, feeling that anticipatory hum historians recognize when the past is about to speak.

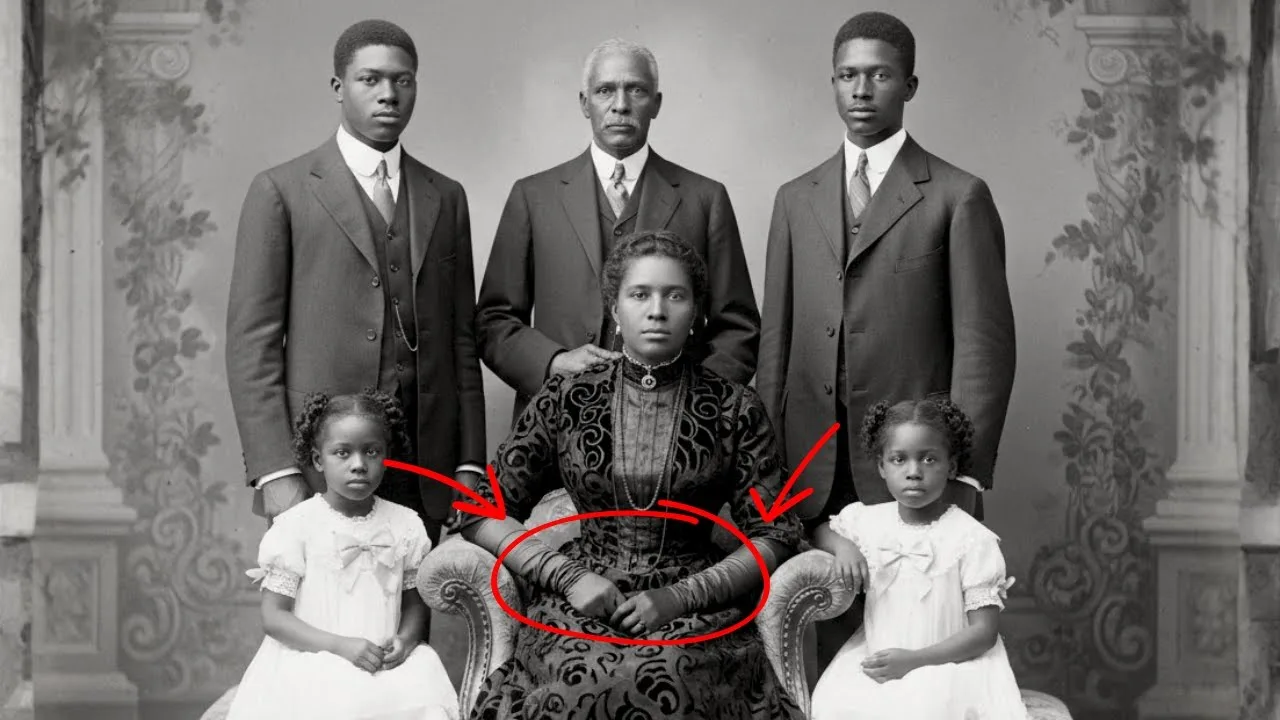

The frame was Victorian—carved with patient detail—and inside lay a remarkable studio portrait marked “J.

Morrison, Portrait Artist, Richmond, VA.” The date on the back, penned in faded ink: June 1875.

A black family of six posed with the solemn dignity of the era: a man in his forties standing at center with his hand on an ornate chair; his wife seated beside him, posture straight, gaze steady; four children arranged around them—two boys, two girls—between six and sixteen.

Their clothes were fine but practical, proof that hard-won stability had become possible in a decade of freedom.

Amelia had catalogued hundreds of such portraits.

In the Reconstruction years, newly freed families sought formal images to claim space in the visual record—to assert progress and humanity in the face of a nation insisting otherwise.

This one was like those—and then it wasn’t.

The mother wore gloves.

Not short silk or mid-length lace, but long gloves that reached nearly to her shoulders under three-quarter sleeves.

Fine kid leather, dark as her dress.

Elegant.

Odd.

Amelia leaned close.

The woman’s face showed calm resolve—a look familiar in portraits of women who had carried families through storms.

But the gloves—why so long? Fashion changed, and personal choice mattered, yet something about those gloves felt purposeful in a way fashion alone did not explain.

She flipped the frame.

On the back: “The family, Richmond, Virginia, June 1875.

May we never forget.”

Amelia took a photo of the inscription, then digitized the image with high-resolution tools and ran contrast adjustments.

Small details emerged: the father’s hands were roughened by labor—carpenter’s knuckles, callused palms.

The children’s expressions were nervous-proud.

The mother’s gloves, under enhancement, revealed faint textures.

Tiny ridges.

Subtle raised lines beneath the fabric.

Her stomach tightened.

She contacted Dr.

Marcus Chen at Virginia Commonwealth University, a forensic imaging specialist with whom she’d worked before.

He brought a scanner, calibrated lights, and a laptop loaded with software that coaxed history out of shadow.

Under infrared shadow analysis and texture mapping, the gloves yielded a hidden topography: pale lines circling the wrist, long healed lash marks on the upper arm.

The scarring ran shoulder to wrist.

The cloth did not conceal.

It only covered.

“She was enslaved,” Amelia said, voice thin in the quiet.

“These are restraint injuries.

Punishment scars.”

Marcus nodded.

“From age estimations, the newest injuries predate the photo by at least a decade.

Before 1865.”

The photograph shifted in meaning.

It was no longer simply a testament to Reconstruction success.

It was also a record of a woman who had carried scars without letting them define the image she insisted the world remember.

To understand who she was, Amelia had to find her.

The photographer’s business—James Morrison, a Scottish immigrant—had opened on Broad Street in 1867 and served both white and black clients.

His appointment books had burned in a district fire.

So Amelia turned to property records, Freedmen’s Bureau files, city directories, census pages—places where names gather dust and stories wait for someone patient enough to coax them back.

She found a deed from 1871: Daniel Freeman, carpenter, purchased a house on Clay Street in Jackson Ward, a neighborhood fast becoming the epicenter of black culture and business.

The deed listed his wife, Clara Freeman, and four children—Elijah, Ruth, Samuel, and Margaret.

Ages matched the photograph.

Then, in Richmond’s Freedmen’s Bureau marriage applications, she found a line item dated 1865: “Daniel Freeman (free prior to war) applying to marry Clara (formerly enslaved) last held by R.

Hartwell, Lancaster County.” Under “distinguishing marks,” someone had written: “Severe scarring on both arms from restraints and punishment.”

The gloves made sense.

The scarring made them necessary.

The family in the photo had become real.

Lancaster County lay in Virginia’s Northern Neck, once home to wide tobacco plantations.

The Hartwell family surfaced in land rolls—prominent, powerful.

Clara Freeman’s earlier life appeared only in fragments—census hints and registry notes—but what Amelia found told of endurance.

By 1870, Daniel worked steadily; by 1875, they owned their home; by 1880, their older children attended school.

Amelia reached out through genealogy forums and preservation groups.

Two weeks later, an email arrived from a retired teacher in Washington, DC: “My name is Dorothy Freeman Williams.

I am the great-great-granddaughter of Clara and Daniel Freeman.”

Dorothy arrived with a worn leather portfolio and tears brighting when she saw the portrait.

“Yes,” she said softly.

“Those are my great-great-grandparents and their children.

I grew up hearing about this photograph.

It disappeared after my grandmother died in 1983.

Someone must have sent it here.”

She opened the portfolio.

Inside lay letters, Freedmen’s Bureau certificates, and a handwritten life story in small, careful penmanship dated 1889.

“My name is Clara Freeman,” it began.

“I was born Clara Hayes in 1831 on the Hartwell Plantation in Lancaster County, Virginia.

I do not know my exact birthday… From age six, I worked in the tobacco fields and stayed there until the day I escaped during the confusion of the war… The Hartwells were not gentle masters.

When I was fourteen, I tried to run away to find my mother… I was caught after three days.

They punished me by shackling my wrists and ankles for six months.

The metal tore into my skin, and I still carry the scars.

Through the years, I was whipped many times… By the time I reached thirty, my arms were covered in scars from wrists to shoulders.”

Dorothy added what Clara hadn’t written: in 1864, with Virginia in chaos and Richmond under siege, Clara fled, walked at night for three weeks, and reached Union lines.

A Freedmen’s Bureau certificate dated April 1865 acknowledged her freedom.

She married Daniel—a free-born carpenter repairing a battered city—within three months.

Dorothy read from a letter Daniel wrote to his sister in 1870: “Clara is the strongest woman I have ever known… She never lets anyone see her arms uncovered.

She makes long sleeves for every dress and wears gloves whenever she steps outside.

She says the scars remind her too much of what she endured, and she doesn’t want our children to grow up seeing those marks and thinking of their mother as a victim.

She wants them to know her strength.”

The portrait’s choice became crystalline.

The long gloves were not shame; they were agency.

Clara decided how history would look at her family.

It was Clara’s idea to take the portrait.

In June 1875, they went to Morrison’s studio.

The receipt—$5—was a week’s wages.

She wore her best dress and gloves made specially for the sitting.

She wrote on the back: “May we never forget.”

“What did she mean?” Amelia asked.

Dorothy’s voice softened.

“She wanted us to remember both the wounds and the resilience.

She wanted us to never forget the price of freedom—and to know that scars, seen or unseen, are signs of survival.”

More layers emerged from Dorothy’s portfolio and memory.

A diary kept by Ruth—the girl on the right—held entries about her mother: “Mama does not speak much about her years before freedom, but sometimes late at night, I hear her weeping softly… I once asked her about the scars on her arms… She told me they were reminders of a past that no longer had power over her.

She said the scars could make her think about cruelty or about strength, and she chose strength.

She covers them because she wants people to see the woman she is now.”

Church records showed Clara organized a mutual aid society for formerly enslaved women.

Meeting notes from 1878 recorded her address: “The scars you carry are signs of survival, not defeat.” A newspaper clipping from 1888 quoted her: “We have made something here that cannot be taken from us… Dignity… Our right to make our own choices.

My children were born free.

They will raise their own children in freedom—that is worth more than any riches.”

By 1880, Daniel’s carpentry shop employed several men; by 1885, city directories listed Clara as a property owner with a rental house.

Elijah and Samuel learned trades; Ruth and Margaret became teachers.

Clara taught herself to read newspapers and keep accounts, writing family stories so memory would not be left to rumor.

To place Clara’s individual story in the broader history, Amelia worked with Dr.

Marcus Bennett, a historian of slavery and Reconstruction.

They crafted exhibition panels that did not shy from brutality: Virginia enslaved nearly half a million people before the war.

Tobacco plantations demanded relentless labor; punishment—whipping, shackling—was used to enforce control.

Shackling scars like Clara’s were tragically common among those who resisted.

And yet, the exhibit balanced injury with achievement: Richmond’s black business district grew in the 1870s; churches, schools, and mutual aid societies flourished; thousands purchased homes and started enterprises, despite white supremacist backlash.

Clara and Daniel’s trajectory, while extraordinary in its details, echoed a larger pattern of determination across the state.

On a warm May night in 2025, the American Legacy Museum opened “Hidden No More,” an exhibition centered on Clara’s portrait.

The photograph hung under gentle light, with an adjacent screen displaying the enhanced image revealing the scars beneath the gloves.

Text panels told both the violence and the victories.

Twenty descendants stood together in a room filled with educators, historians, students, journalists, and neighbors.

Amelia stepped to the podium.

Behind her, Clara’s calm face anchored the room.

“For 149 years,” Amelia said, “this photograph was known as a beautiful portrait of a successful black family in postwar Richmond.

Technology revealed what Clara chose not to show—the scars she carried from what she survived.

By discovering what she hid and why, we find something even more powerful: Clara’s deep act of self-definition.

She did not conceal her scars from shame.

She refused to let them define the image she wanted handed down.

She wanted her children—and every generation after—to see her as a woman of courage and accomplishment.”

She gestured to the descendants.

“They are living proof of what she and Daniel built: teachers, doctors, engineers, artists, business owners.

They carry her values—resilience, dignity, devotion to family and community.”

Dorothy took the microphone.

“My great-great-grandmother Clara died in 1904 at seventy-three.

Family stories say someone asked her near the end if she regretted covering her scars in the portrait instead of showing them as evidence.

Clara said, ‘I wanted the world to see what we built, not what others tried to break.’”

Visitors lingered long after the speeches, standing before the portrait and the enhanced image.

Some cried softly.

Some held hands.

Many read Clara’s 1889 words, displayed on the wall: “The scars on my arms exist, and I will never deny them.

But they are not the full story of my life.

I am also a wife, a mother, a neighbor, a woman who lived through suffering and still built something strong and beautiful out of the ruins of bondage.”

It had looked like nothing more than a family photograph.

Yet the woman’s gloves hid a terrible secret—and a profound act of power.

Clara’s choice to cover what had been done to her was not about erasing pain.

It was about deciding how a life should be remembered: not as a ledger of injuries, but as an accumulation of love, work, learning, and the quiet insistence that dignity belongs to those who claim it.

News

How A Texas Female Police Officer Fulfilled A Prisoner’s Last Wish — What He Asked Will Shock You

The request arrived like a fracture line—thin, sudden, and capable of breaking a life in two. Rebecca Martinez, twenty-six, steady-handed…

The most BEAUTIFUL woman in the slave quarters was forced to obey — that night, she SHOCKED EVERYONE

South Carolina, 1856. Harrowfield Plantation sat like a crowned wound on the land—3,000 acres of cotton and rice, a grand…

(1848, Virginia) The Stud Slave Chosen by the Master—But Desired by the Mistress

Here’s a structured account of an Augusta County case that exposes how slavery’s private arithmetic—catalogs, ledgers, “breeding programs”—turned human lives…

The Most Abused Slave Girl in Virginia: She Escaped and Cut Her Plantation Master Into 66 Pieces

On nights when the swamp held its breath and the dogs stopped barking, a whisper moved through Tidewater Virginia like…

Three Widows Bought One 18-Year-Old Slave Together… What They Made Him Do Killed Two of Them

Charleston in the summer of 1857 wore its wealth like armor—plaster-white mansions, Spanish moss in slow-motion, and a market where…

The rich farmer mocked the enslaved woman, but he trembled when he saw her brother, who was 2.10m

On the night of October 23, 1856, Halifax County, Virginia, learned what happens when a system built on fear forgets…

End of content

No more pages to load