In the late 1980s, Skid Row exploded onto the hard rock scene with hits like “18 and Life,” “I Remember You,” and “Youth Gone Wild.”

Their debut album went five times platinum in the U.S.and sold millions more worldwide, propelling the band to instant stardom.

Yet behind the scenes, a surprising and controversial financial arrangement meant that a significant portion of the royalties from these iconic songs didn’t go to the band or their label—but instead to rock legends John Bon Jovi and Richie Sambora.

This is the story of how Skid Row got famous… and then Bon Jovi sent them an invoice.

The roots of this unusual deal trace back to two aspiring musicians from New Jersey: Dave “Snake” Sabo and John Bon Jovi.

As young men scraping by, they made an unspoken pact — whoever made it big first would reach back and help the other.

There were no contracts, just a promise born out of shared struggle and hope.

By 1983, John Bon Jovi was no longer dreaming; he was breaking through.

After releasing Bon Jovi’s self-titled debut album in 1984 and fighting hard for radio and MTV exposure, the band’s 1986 album *Slippery When Wet* detonated across the music world.

It went 12 times platinum, filling arenas and dominating airwaves, cementing Bon Jovi’s place as rock royalty.

Dave Sabo had a brief stint playing early shows with Bon Jovi but was soon replaced by Richie Sambora.

Accepting reality, Sabo set out to build his own band — Skid Row.

Sabo assembled a group including vocalist Matt Fallon and began searching for a breakthrough.

By 1987, Bon Jovi kept his promise and introduced Skid Row to Doc McGee, the manager who handled Bon Jovi and Mötley Crüe.

McGee liked the band’s sound and look but wasn’t sold on Fallon’s vocals.

He bluntly told them: without a strong frontman, they would remain stuck playing Jersey bars forever.

Fate intervened when Bon Jovi’s parents attended a wedding and discovered Sebastian Bach, a Canadian singer with a powerhouse voice.

Bach was invited to audition and blew everyone away.

By early 1988, Fallon was out, Bach was in, and Skid Row’s transformation from local bar band to major label contender was complete.

In mid-1988, armed with Bach’s vocals and a tight lineup, Skid Row signed with Atlantic Records, thanks largely to Doc McGee’s influence.

They were also secured as the opening act on Bon Jovi’s *New Jersey Syndicate* World Tour — one of the biggest rock tours of the decade.

But there was a catch.

Doc McGee presented a condition for the record deal and tour slots: Skid Row had to give up a large portion of their publishing rights — not to the label or their manager, but to John Bon Jovi and Richie Sambora’s new venture, The Underground Music Company.

This meant that while the band would receive artist royalties and some income from album sales, the lion’s share of publishing royalties — the money from radio spins, MTV airplay, movie placements, and more — would flow directly to Bon Jovi and Sambora.

The band knew it was a bad deal.

They voiced their concerns, but hungry for a break and staring at the door to fame swinging open, they took it anyway.

Skid Row stormed onto the scene in January 1989 with their debut album, which quickly went five times platinum.

Hits like “Youth Gone Wild,” “18 and Life,” and “I Remember You” dominated airwaves and MTV, turning the band into bona fide rock stars.

But with every spin and every video play, the royalties didn’t primarily fill Skid Row’s pockets.

Instead, half—and by some estimates, up to 75%—of the publishing royalties went to John Bon Jovi and Richie Sambora.

Inside the band, frustration grew.

Bassist Rachel Bolan and guitarist Snake Sabo struggled to digest watching the two men who had helped open doors for them reap the financial rewards of songs they didn’t write or perform on.

Sebastian Bach was the most vocal, publicly demanding a fix to the publishing arrangement.

By 1990, tensions reached a boiling point.

Bach confronted the band’s lawyer, demanding a 25% stake in all revenue streams or he would leave.

The band caved — not out of desire, but necessity.

Without Bach’s voice and presence, Skid Row was nothing.

This marked a turning point.

The band renegotiated their contracts, ending the skewed publishing deal.

Their next album, *Slave to the Grind* (1991), was the first where they owned all the rights outright.

It debuted at number one on the Billboard charts — the first metal album ever to do so — and proved that Skid Row was a powerful force independent of Bon Jovi’s shadow.

Despite the renegotiation, the financial fallout from the first album’s publishing deal never fully disappeared.

Every time “18 and Life” or “I Remember You” plays on classic rock radio, gets streamed on Spotify, or appears in a movie or commercial, Bon Jovi and Sambora’s names still appear on the royalty checks.

Richie Sambora reportedly once expressed guilt and offered to return his share, but Snake Sabo has confirmed no such repayment ever occurred.

The money continues to flow quietly, a lasting reminder of the deal that launched Skid Row but came at a steep price.

The story highlights the complex world of music royalties.

Publishing rights — ownership of the song’s composition, lyrics, and melody — are distinct from recording rights.

Whoever owns publishing gets paid first, before artists, labels, or producers.

Royalties come in several forms:

– Performance royalties: Paid when songs are played on radio, TV, concerts, or streaming platforms.

– Mechanical royalties: Earned from physical sales or digital streams.

– Sync royalties: Paid when songs are used in movies, TV shows, or commercials.

For Skid Row’s first album, these income streams mostly benefited Bon Jovi and Sambora, due to their ownership of the publishing rights.

Skid Row’s experience serves as a cautionary tale about the importance of owning your music.

While the band gained fame and success, they sacrificed long-term financial rewards to get there.

As Snake Sabo put it bluntly: “We signed a shitty deal.We knew it.But it got us on the biggest tour in the world.”

John Bon Jovi opened the door for them — but he also kept the keys.

Skid Row’s journey from hungry Jersey kids to platinum-selling rock stars is a testament to talent and perseverance.

Yet their story also exposes the harsh realities of the music industry, where deals can be as much about business as art.

Even decades later, the royalties from their biggest hits still flow into the pockets of those who didn’t write or perform the songs.

It’s a powerful reminder: in music, sometimes owning the rights is more valuable than playing the notes.

For aspiring musicians and fans alike, the moral is clear — own your work, or someone else will.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

News

At 95, Robert Wagner FINALLY Confirms

For over four decades, the tragic death of Hollywood star Natalie Wood on a cold November night in 1981 has…

Whatever Happened to Humphrey Bogart’s 2 Children

Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall are among Hollywood’s most iconic couples, their romance and legendary careers etched into cinematic history….

The Princess Who Nearly Destroyed The Monarchy

Princess Margaret, the younger sister of Queen Elizabeth II, lived a life marked by glamour, scandal, and tragedy that challenged…

Putin Backs Out of Peace Talks, Will Trump End Birthright Citizenship?

In his May 15, 2025, broadcast of *No Spin News*, Bill O’Reilly tackled the deep divisions plaguing the United States,…

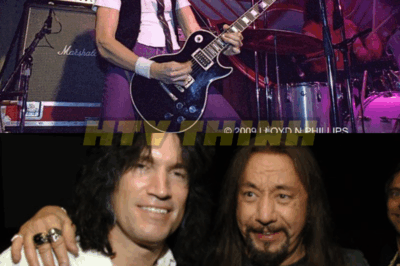

At 64, Tommy Thayer SHOCKS Fans About KISS..

In the world of rock music, where legends are often defined by wild antics and larger-than-life personas, Tommy Thayer’s story…

Diddy Loses It in Court After Justin Bieber Publicly Supports Cassie on Day 2 of the Trial!

The courtroom was tense and charged with emotion on day two of the high-profile trial involving music mogul Sean “Diddy”…

End of content

No more pages to load